The rise of kingship beyond big cities: new discoveries from two sites in Turkey

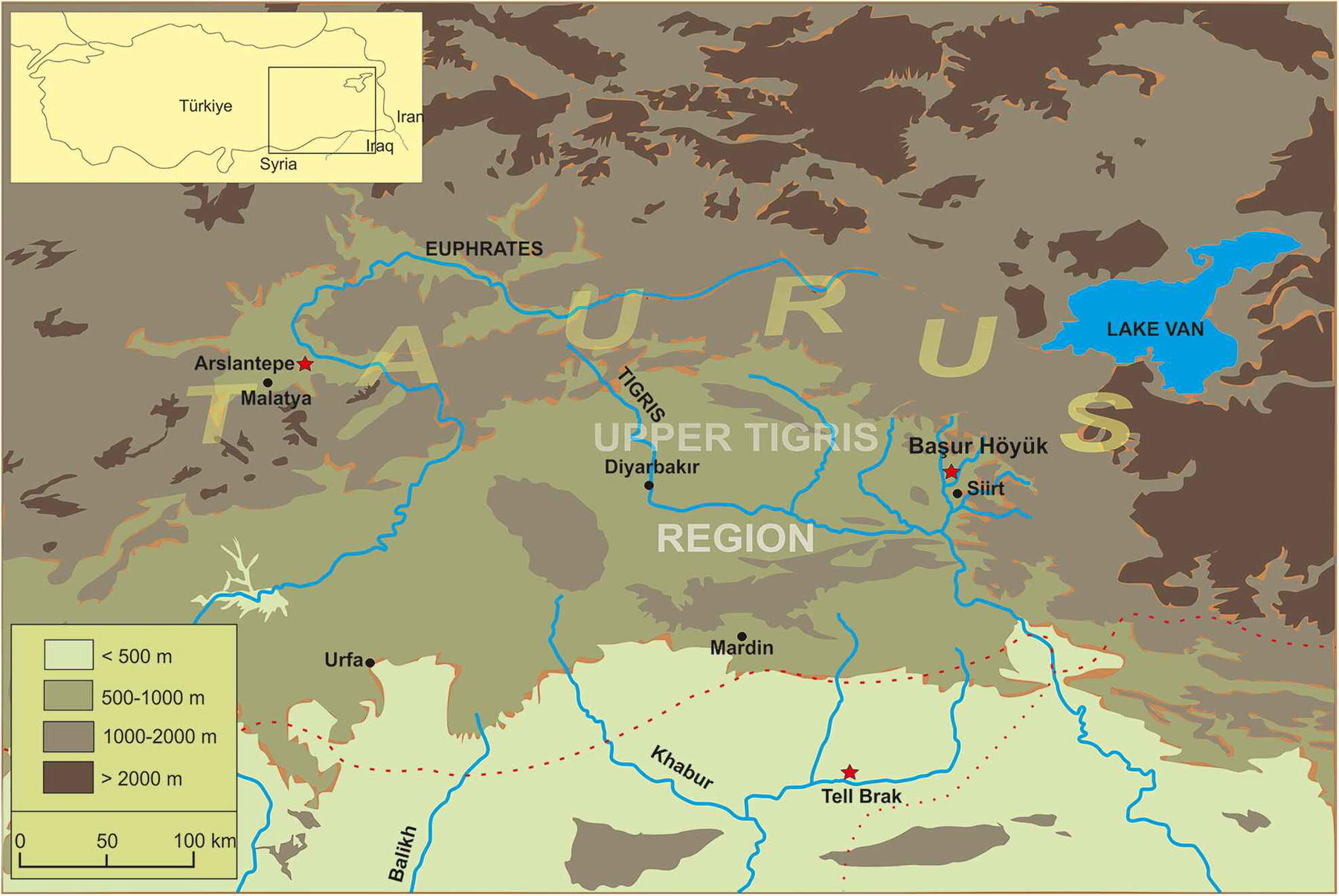

A few weeks ago, the Cambridge Archaeological Journal published a survey that is raising interest in the academic community. The article, a result of years of excavation and analysis at two important archaeological sites in Turkey, Arslantepe and Başur Höyük, proposes new interpretations of the emergence of early political structures and elites during theBronze Age, a period believed to be dominated by Mesopotamian cities. In particular, the discoveries at the two sites seem to challenge the idea that the emergence of kingship was closely linked to urbanization and the concentration of power in urban centers such as that of ancient Babylon. The studies conducted by the Cambridge indicate that the social and political evolution of the Bronze Age was more complex than expected, with the emergence of noble classes arising not solely from the growth of large metropolises, but from local dynamics and control of strategic natural resources.

Arslantepe: the birth of kingship outside urban centers.

Located on the Malatya plain in eastern Turkey, the site of Arslantepe dating back to 3300 B.C. has been the subject of extensive excavations in recent decades. What makes the site so important, however, is the presence of palaces and burials dating back to 3000 BCE. (one among them identified as the oldest known royal tomb at Arslantepe), which challenge traditional theories that the formation of complex political structures (such as those leading to the establishment of kingship), were possible precisely only in large, already developed cities, such as Uruk, an ancient city in southern Babylonia, or Sumer. The remains of the monumental palaces at Arslantepe thus suggest that the aristocracy had also developed in more isolated areas, where the elite was able to exercise power through resource management, territorial protection, and centralization of ritual practices. Moreover, in addition to the ruined palace complex, the Arslantepe site has a number of objects found in funerary contexts that indicate the existence of a true royal court. Their wealth, also derived from the use of the materials, could suggest that the buried individuals belonged to a very high rank, probably connected to a local ruler.

In any case, what makes the site even more remarkable is the presence of evidence of human sacrifices in funerary contexts. Indeed, during excavations, remains of individuals sacrificed at high-ranking burials were found. But why is there talk of human sacrifice? In a context in which power was closely linked to the control of resources and the protection of communities, sacrifices may in fact have been intended to reinforce the authority of local rulers and to consolidate the link between the divine and political power. Findings from Arslantepe indicate that, in some ancient Bronze Age societies, sacrifices were employed to consecrate the figure of the ruler and ensure the prosperity of the kingdom, legitimizing his authority and power over the population.

Başur Höyük: a transit point for natural resources

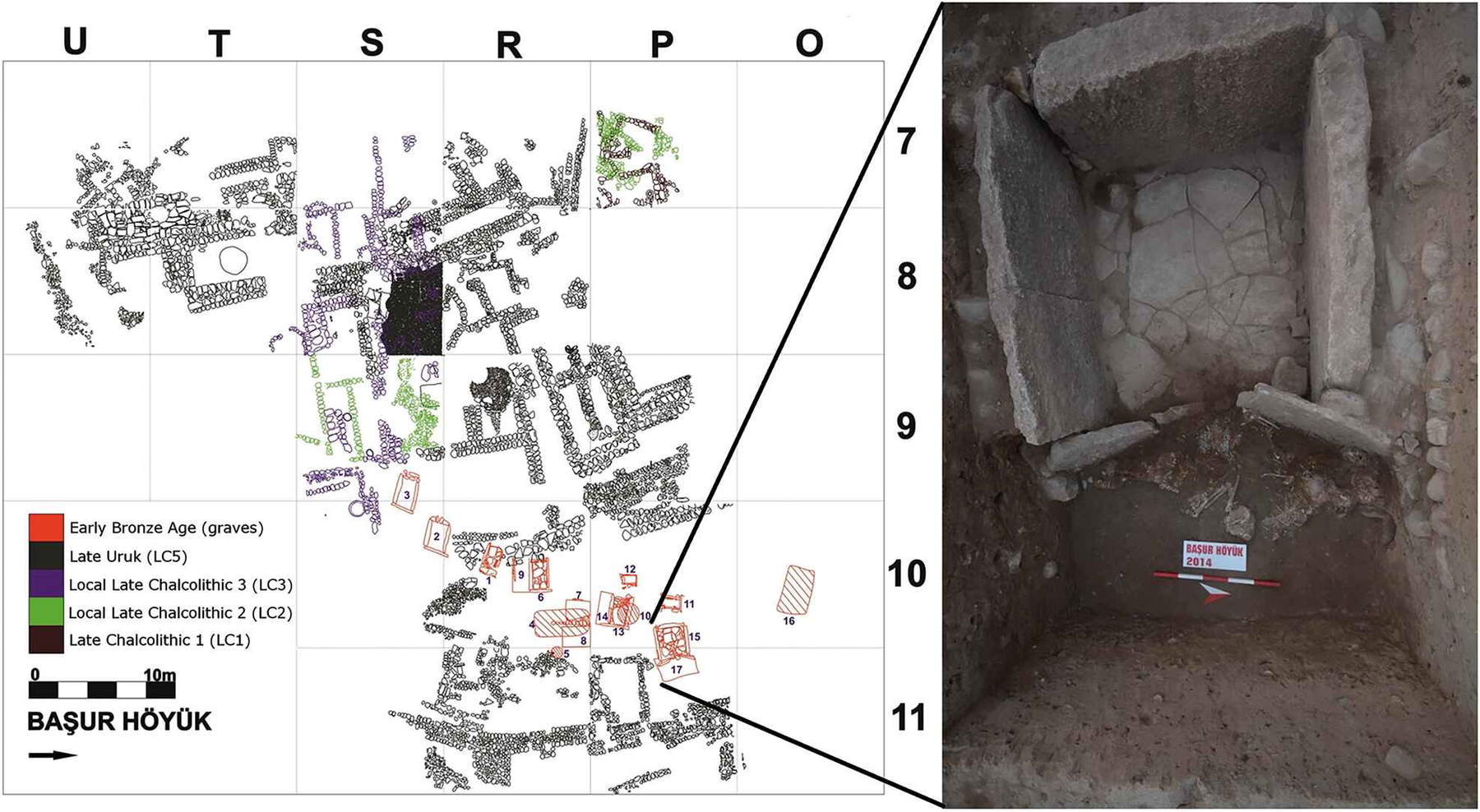

In contrast, the site of Başur Höyük, located in the mountainous region of southeastern Turkey, is a research site that has recently revealed new discoveries about the formation of elites in the Bronze Age. Located on a hill strategically positioned along the trade routes that connected Mesopotamia to the Caucasus and Iran, Başur Höyük was a trading center and transit station for natural resources, active in the late fourth and early third millennia BCE. As in the case of Arslantepe, the Başur Höyük site has archaeological discoveries that have identified ritual structures and collective tombs that seem to confirm the existence of a hierarchical society.

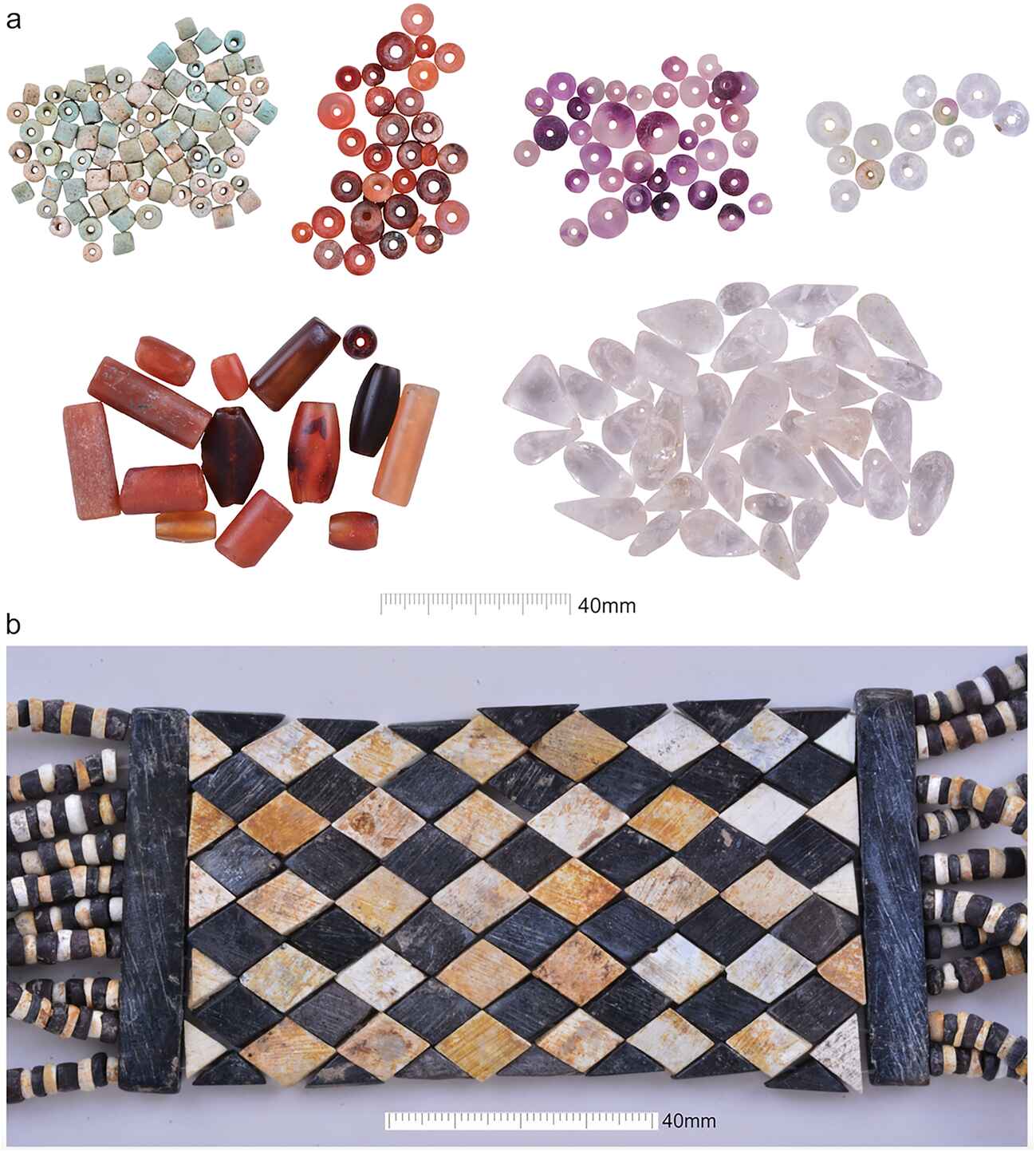

After the collapse of the Uruk system between 3100 and 2800 BCE, Başur Höyük emerged as a center for the performance of funerary rites, some of them particularly conspicuous and sometimes violent. Indeed, 18 tombs have been discovered in the southeastern area of the site, including stone cists, simple pits, and pit graves with stone hoods, all excavated in the architecture of the late Chalcolithic period. In addition to this, nearly 1,000 metal objects, including insignia and weapons, were found in the necropolis, carefully wrapped in textiles, as well as about 100,000 stone beads, made of materials such as limestone, agate, amethyst, rock crystal (quartz), steatite, azurite, faience and sea shells. The objects, along with an equally varied ceramic assemblage, attest to the continuous access to international trade networks that followed the expansion of the Uruk civilization. The stone tombs of Başur Höyük are also notable for the simultaneous burial of multiple individuals in ranked orders. The data might suggest that, in the early Bronze Age, there were male groups associated with initiation rites or warrior cults: in fact, chromosomal analysis revealed the presence of individuals of both sexes and, in the early stages of the Başur Höyük necropolis, perhaps even more women. Nevertheless, among the most striking objects were several hundred copper objects cast by the lost-wax technique, such as amulets with animal-shaped tops that imitated the shape of cylindrical seals, banners and scepters, chalices and medallions with attached figures of wild bulls, goats and birds.

Implications for the history of elites

The presence of human sacrifices at both sites thus sheds light on a less analyzed aspect of Bronze Age societies: the connection between political power and religious rituals. Sacrifices, in fact, were not considered acts of violence. Rather, as noted above, they were symbolic tools for communicating power, the sacredness of the ruler, and divine protection, and in societies where social divisions were strong and resources limited. At a time when control of territory and resources was crucial for survival, the use of ritual practices, such as precisely sacrifices, also had political significance. Human sacrifice served as a manifestation of power, with the ruler presenting himself as an intermediary between the earthly and divine worlds.

Although it is still possible to argue that metropolises such as Uruk or Babylon played a decisive role in the formation of early political structures, the discoveries at the two sites of Başur Höyük and Arslantepe indicate that other social dynamics may have contributed to the emergence of kingship and ruling classes.

Although the sites were influenced by trade with the great Mesopotamian civilizations, they appear to have followed different paths, indicating that the formation of elites in the regions was a more diverse phenomenon and less tied to a centralized urban model. Natural resources, such as copper ore and fertile land, played a key role in many of the areas mentioned, where geographic location and control of resources were crucial to the establishment of local powers. Such dynamics therefore demonstrate how the Bronze Age was characterized by a plurality of political and social experiences. While Mesopotamia remains central to the history of antiquity, the investigation of new peripheral realities prompts scholars to rethink the complexity of pre-urban history and to consider a variety of factors that contributed to the formation of stratified Bronze Age societies.

|

| The rise of kingship beyond big cities: new discoveries from two sites in Turkey |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.