The first artists? They were largely children: a study of rock art

The artists of prehistory? Many of them were children. A Spanish study, published a few days ago in the Journal of Archaeological Science, signed by Verónica Fernández-Navarro and Diego Garate of the University of Cantabria in Santander, and Edgard Camarós of the University of Cambridge, came to this conclusion. The three scholars examined more than 700 handprints left on cave walls in France, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy, as this is definitely important evidence for drawing information about prehistoric populations, and the morphometric studies revealed that in the graphic production of prehistoric humans the participation of children and even infants was very extensive. The results therefore go so far as to state that rock art was considered a collective action in which different strata of the population took part.

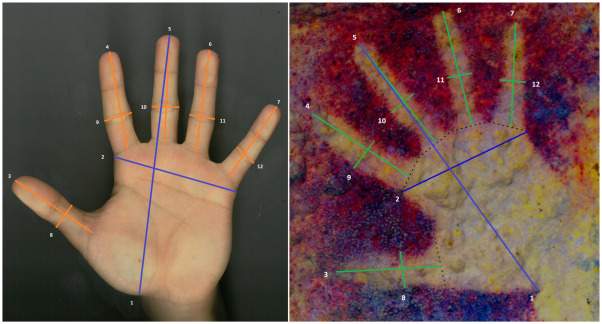

The three scholars analyzed a sample of footprints on a number of Spanish caves (El Castillo, Maltravieso, Fuente del Salín, Fuente del Trucho, La Garma) dating back to the Upper Paleolithic, chosen because of the large number of footprints preserved in them and their state of preservation, and made 3-D models of them and then measured them. The results were then compared with measurements of hands from a present-day population, divided into different age and sex groups in order to determine the parameters of the morphometric study of the archaeological sample (the study was limited to an Iberian population in order to find the maximum possible correspondence with the geographical area of the archaeological sample). The novelty of the study lies precisely in the 3-D modeling: “most previous studies in this field,” the paper states, “have relied on two-dimensional photographs or measurements of motifs taken directly. These methods can lead to significant errors, mainly due to the transformation of the uneven natural surface of the cave wall into a flat representation that distorts the actual measurements and causes biometric distortion. In contrast, our methodology approaches the sample through three-dimensional documentation that allows us to measure with high levels of accuracy and without optical distortion. From those 3D models, 2D orthoimages are created, allowing us to obtain a 2D image without conical deformations, typical of traditional 2D images, from which we can extract true orthogonal measurements. In addition, this methodology can be applied and replicated for any type of archaeological documentation, while it can also be complemented and implemented with other types of analysis, such as geometric morphometry.”

After comparisons, a group of twenty people were selected and asked to make impressions with a pigment on a rock. A photogrammetric scale model was made of each of these hands imprinted on the rock, and several measurements were taken, following the metric parameters of the study, to compare their morphometry with real hands. After this experiment, an average error was established from the values obtained for the deformations in each of the paintings when they were compared with the original hand models. This “average strain index” was calculated for hand length and width and finger length and width. Finally, this correction was applied to the archaeological pattern measurements to align the archaeological and modern samples.

The data obtained from the modern sample were compared with the archaeological data. First, the validity of the chosen biometric parameters was checked and the strain index was calculated for the size differences between the actual scanned hands and their stamped representations. Next, the archaeological data were analyzed both in general and individually for each of the five archaeological cases used in the study. The results showed that children are a constant presence in the caves: in some, the handprints of children as young as 2 years old reach over 9 percent, while similar percentages apply to children up to 7 years old. Extending the research to children up to 12 years old, however, results in percentages exceeding 30 percent.

“Graphic activity,” the scholars write, “appears to be a field open to the whole community, in which both children and adults play a role in the production of motifs. It would not have been an activity strictly for men and subsistence, as has traditionally been professed, without considering that women and children might have been involved. Likewise, the participation of such young members of society, even children, suggests that this activity was connected with a goal of group cohesion and reaffirmation, through art.” However, it is important, the archaeologists specify, “to remember that when conducting bioarchaeological and anthropological studies of prehistory , it is necessary to be aware of the possible differences between prehistoric and modern study populations, especially if there is any kind of comparison between the two.”

|

| The first artists? They were largely children: a study of rock art |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.