In Pompeii, a new ongoing archaeological excavation in the area of theinsula of the Casti Amanti has unearthed a rare housing typology that testifies to social and cultural change in first-century AD Rome. The house, which takes the provisional name “House of Phaedra” because of a recently found fresco of Hippolytus and Phaedra, is striking for its decision to forgo the atrium-a traditional element of Roman domestic architecture-in favor of a more modern and versatile arrangement of spaces.

This dwelling is thus an example of a domus without an atrium, a choice that differs from the typical pattern of Roman houses of the republican period, in which the central atrium represented both the centerpiece of representation for the family and the space designated for the celebration of family virtus. This open space, with the reception room(tablinum) and display areas for trophies and family portraits, represented the social scene in which the owner interacted with his clientes and demonstrated the honor and dignity of his lineage. The gradual disappearance of the atrium in the houses at Pompeii testifies to the evolution of social relations and housing practices, paving the way for a more private and secretive concept of domesticity, freed from the need to flaunt one’s rank through the architecture of the house.

“It is an example of public archaeology or, as I prefer to call it, circular archaeology: conservation, research, management, accessibility and fruition form a virtuous circuit,” explains Park Director Gabriel Zuchtriegel. “Excavating and restoring under the eyes of visitors, but also publishing data online in our e-journal and on the open.pompeiisites.org platform means giving back to the society that finances our activities through tickets, fees and sponsorships the full transparency of what we do, not for the sake of a small circle of scholars, but for everyone. Archaeology must belong to everyone because only in this way will we create understanding toward the archaeologists who work all over Italy on construction sites as part of so-called preventive archaeology. If the construction site of the metro or a road is delayed because of archaeological discoveries, visiting Pompeii and observing the work of archaeologists and restorers can help us understand why it is worth documenting and safeguarding the traces of the generations who lived before us.”

In ancient Rome, the structure with atrium had been established for about six centuries, but on the eve of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, signs of a transformation were already visible . More modern houses had a courtyard-peristyle around which reception rooms were arranged. A later example of this change is the House of Diana in Ostia, built in the first half of the second century AD, where the peristyle replaced the atrium as the central space and the courtyard became the new focus of domestic life.

Recent studies reveal that about 20 percent of the catalogued dwellings in Pompeii retain an atrium, while many of the others, mostly workshops, small apartments or production spaces, lack one. However, some larger houses with sophisticated decorative elements deviate from the courtly model of the atrium, as in the case of the House of Phaedra. Here, the lack of an atrium is not dictated by space limitations-which would have allowed for the inclusion of a narrow atrium anyway-but by a specific cultural choice.

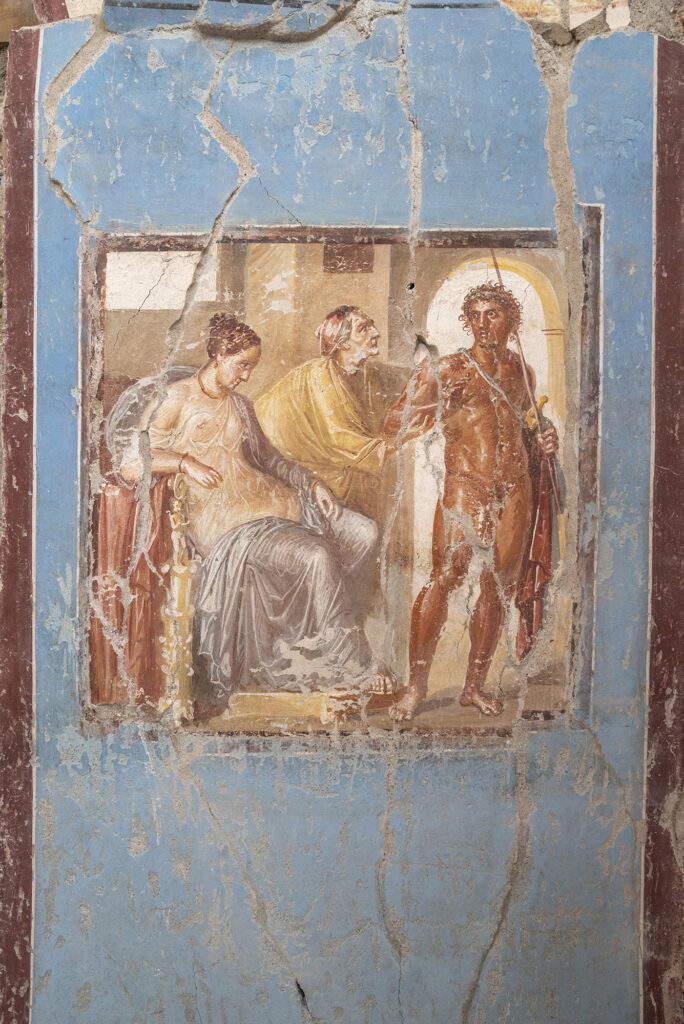

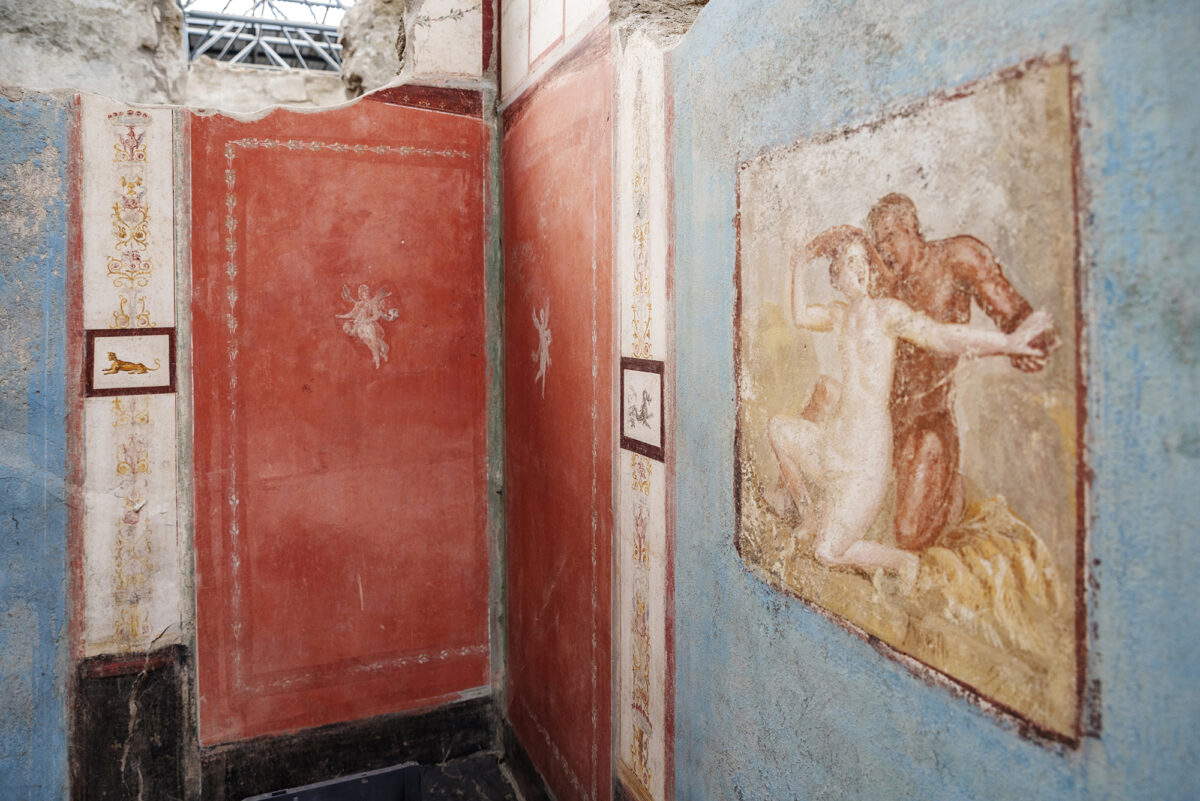

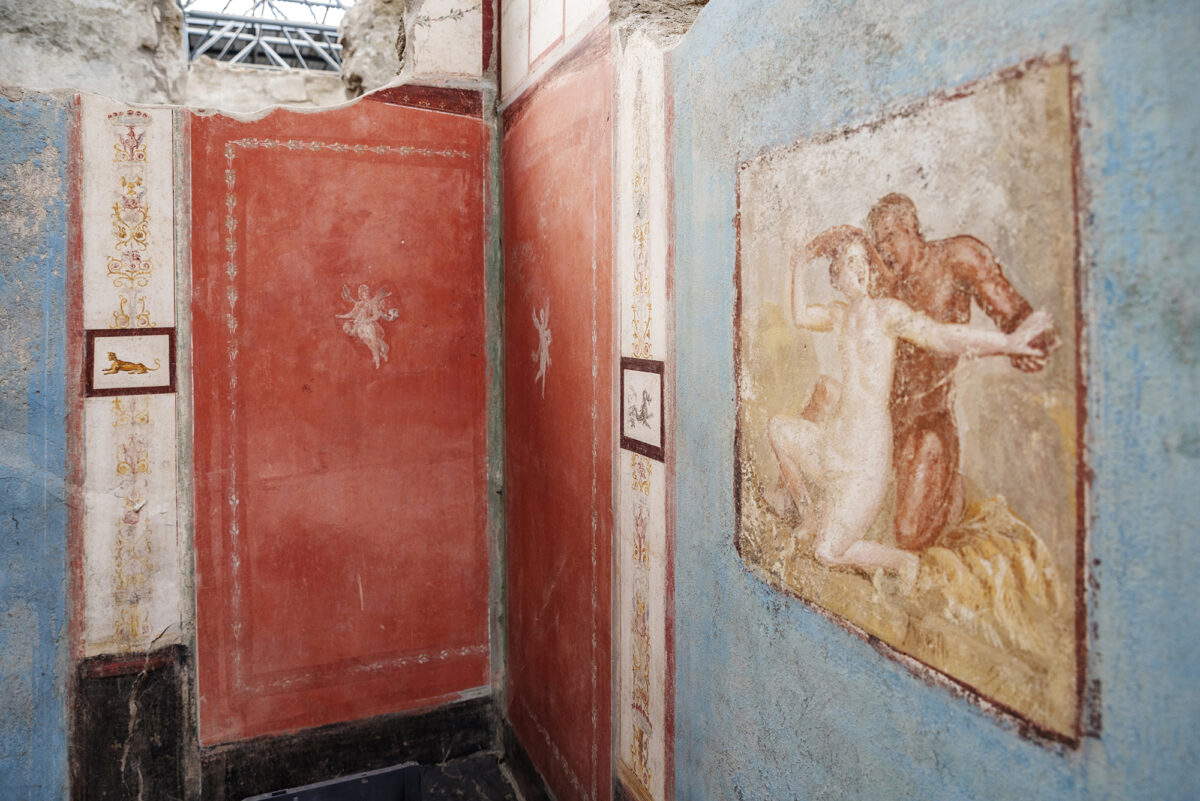

In the House of Phaedra, located in the insula of the Casti Amanti, fine frescoes were found that demonstrate a high artistic quality. In addition to the mythological scene of Phaedra and Hippolytus, which inspired the provisional name of the house, paintings depicting a symplegma, or intercourse, between a satyr and a nymph, a divine couple-probably Venus and Adonis-and other figures, including a damaged scene that is speculated to depict the judgment of Paris, were found.

The structure of the house, with an area of about 120 square meters, shows a distribution of spaces oriented toward functionality and representation in a private key: a productive and commercial environment, located toward the street and developed on two floors, replaces the traditional atrium as the first access space to the house. Behind this environment, three rooms decorated in IV style open up, including a kind of reception room or family office, which seems to inherit the function of what was once the tablinum.

The other main rooms are developed around a small courtyard-peristyle, an element that alludes to the central gardens of the great Roman villas. In this courtyard, decorated by a lararium, remains of sacrifices were found, probably offered just before the eruption. From here there is access to the kitchen, latrine, and other reception rooms, including a room decorated with mythological frescoes that give the house a prestigious status.

The renunciation of the atrium in the domus of Pompeii seems to reflect a change in the needs of society at the time. Until the first century CE, the atrium constituted a space of representation, where the owner displayed trophies, portraits, and other symbols of his prestige. Over time, however, the Romans began to see the dwelling as a more private place, and personal dignitas shifted from the architectural elements to the person himself. In later eras, clothing and accessories began to define the rank and social function of individuals, a trend that peaked in the late imperial age.

The decline of the atrium also signaled a different relationship between the family and the home. In ancient Rome, the domus was a space that represented the gens, or family household, in its entirety. As the centuries passed, there was a gradual shift to a more individualistic conception, where the social role of the individual became independent of the household to which he or she belonged.

Archaeological evidence, such as that from the House of Phaedra, tells a story of transformation that affects not only domestic architecture, but also the habits and social identity of ancient Romans. Some scholars believe that it was precisely freedmen and merchants of modest origins who first adopted this new housing model, giving rise to a trend that was destined to expand over time.

A research project led by Professor Marco Galli of La Sapienza University is deepening the study of textiles and clothing found in Pompeii. The results could confirm the hypothesis of a shift in expressions of status from the architectural context to the personal, shedding light on a cultural evolution that led to a way of living and experiencing the home that was profoundly different from that of previous centuries.

Pompeii in 79 CE thus seems to offer us not only a glimpse into the daily life of the time, but also valuable clues about the long process of transformation of Roman society, which would later lead to the emergence of a new form of social representation based less on material structures and more on individual attributes.

|

| Pompeii, House of Phaedra discovered, a rare domus without an atrium. Which also has an erotic fresco |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.