A group of German researchers from theUniversity of Cologne (who are, moreover, young and just beginning their academic careers: Svenja Bonmann, Jacob Halfman and Nathalie Korobzów) have succeeded in deciphering for the first time anancient and mysterious language spoken in theKushan Empire, which formerly occupied present-day Afghanistan, parts of present-day Pakistan, northern India and an area between Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The writing system used for this language had been discovered in the 1950s, when archaeological excavations in Central Asia unearthed several dozen inscriptions in hitherto unknown characters. It had been found that the “unknown Kushan script,” as it came to be renamed, was a writing system that was in use in parts of Central Asia between about 200 B.C. and 700 A.D. and can be associated with both the early nomadic peoples of the Eurasian steppe, such as the YuèzhÄ«, and the ruling Kushan dynasty. The Kushans founded an empire that, among other things, was responsible for the spread of Buddhism in East Asia. They also created monumental architecture and works of art.

Until now, several dozen mostly short inscriptions were known of this enigmatic language. The inscriptions, which vary in length between fragments of two or three characters and longer inscriptions with several lines of text, have been discovered in an area extending geographically from present-day Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to southern Afghanistan. Most of them are clustered in the territory of ancient Bactria, located between the Hindukush in the south and the Hisar mountain range in the north.

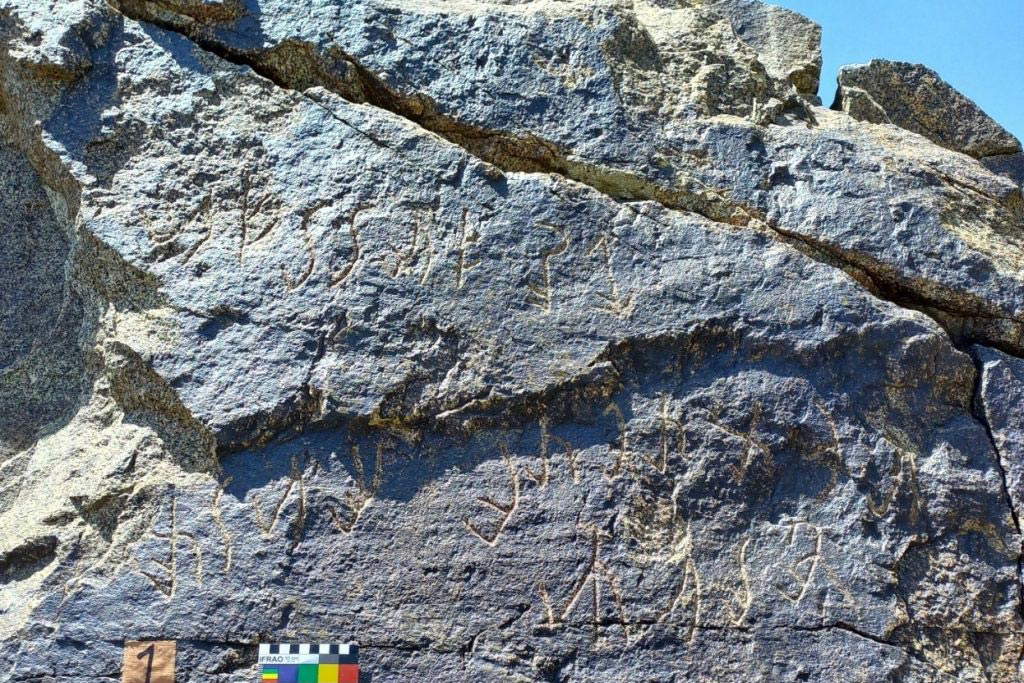

Despite several attempts at decipherment, the unknown writing was still considered illegible. The discovery by Tajik archaeologist Bobomullo Bobomulloev of two new inscriptions in the unknown script in the Almosi Gorge (in Tajikistan, about 30 kilometers from the capital Dushanbe), including a probable bilingual text with Bactrian, was the turning point: this discovery in fact allowed the substitution of plausible phonetic values for several signs of the unknown script and paved the way for a later determination of other phoneme-grapheme correlations of the writing system. The research team’s findings suggest that the script served to record a previously unknown central Iranian language.

The team applied a methodology based on the way unknown scripts have been deciphered in the past, such as Egyptian hieroglyphs through the celebrated Rosetta Stone, or even the ancient Persian cuneiform script or the Greek Linear B script: thanks to the known content of the bilingual inscription found in Tajikistan (Bactrian language and unknown Kushan script) and the trilingual inscription from Afghanistan (Gandhari or Middle Indo-Aryan, Bactrian and unknown Kushan script), Bonmann, Halfmann and Korobzow were able to gradually draw conclusions about the type of writing and language.

In the text appears the named emperor Vema Takhtu, which appeared in both parallel Battrian texts, and by the title “King of Kings,” which could be identified in the corresponding sections in the unknown Kushan script. Above all, the title proved to be a good indicator of the underlying language. Step by step, using the parallel text in Bactrian, linguists were able to analyze additional character sequences and determine the phonetic values of individual characters.

According to the research team, the Kushan script recorded, as anticipated, a completely unknown Central Iranian language, which is not identical to either Battrian or the language known as “saka Khotanese,” once spoken in western China. The mystery language probably occupies an intermediate position in the development between these languages. It could be the language of the settled population of northern Bactria (over part of the territory of present-day Tajikistan) or the language of some nomadic peoples of Inner Asia (the YuèzhÄ«), who originally lived in northwestern China. For a time, it apparently served as one of the official languages of the Kushan Empire along with Bactrian, Gandhari/Middle Indo-Aryan, and Sanskrit. The researchers have also proposed a name, at least tentative, to christen this newly identified language: "Eteo-Tocharian."

Now the group is planning future research trips to Central Asia in close collaboration with Tajik archaeologists, as new finds of additional inscriptions are expected and potential promising sites have already been identified. Researcher Svenja Bonmann, first signatory of the article announcing the discovery, published in the scientific journal Transactions of the Philological Society, commented, “Our decipherment of this script may help improve our understanding of the language and cultural history of Central Asia and the Kushan Empire, similar to the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs or Maya glyphs for our understanding of ancient Egyptian or Maya civilization.” The researchers’ work has enabled them to decipher about 60 percent of the characters of this mysterious language, and scholars are currently working to decipher everything else as well.

Pictured is the stone with the text discovered in 2022 by archaeologist Bobomulloev.

|

| Germany, researchers succeed in deciphering ancient and mysterious language of Kushan empire |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.