This is where the fossils that Leonardo da Vinci mentioned in the Leicester Codex came from

The. Leonardo da Vinci’s paleontology laboratory? According to a team of researchers from several institutes, it was located in theApennines of Piacenza. Of course, we are not talking about an actual laboratory, but simply the place of origin of the fossils Leonardo mentions in the Leicester Codex. The discovery bears the signature of Andrea Baucon, a paleontologist from the University of Genoa, who led the research team including Girolamo Lo Russo (ichnologist, Natural History Museum of Piacenza), Carlos Neto de Carvalho (geologist, Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark/Istituto D. Luiz, Portugal), and Fabrizio Felletti (geologist, University of Milan). The study was published in the March issue of the geology journal RIPS.

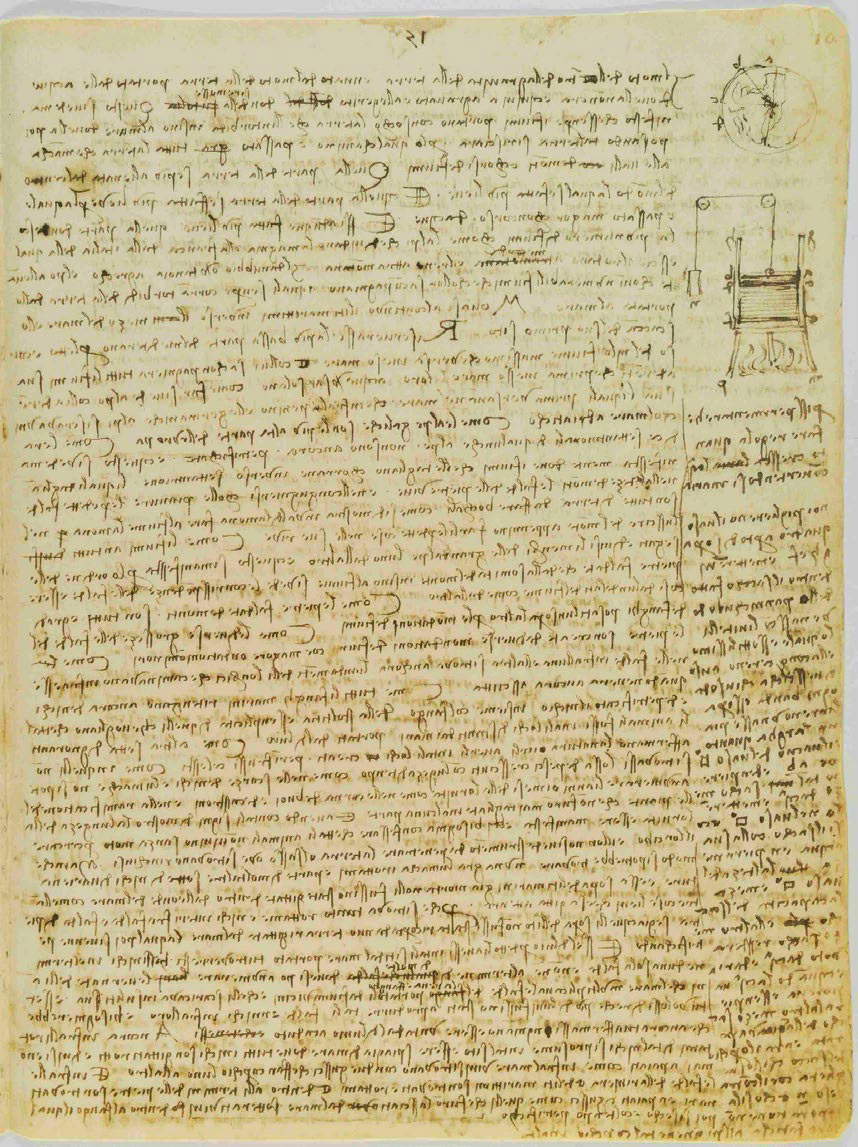

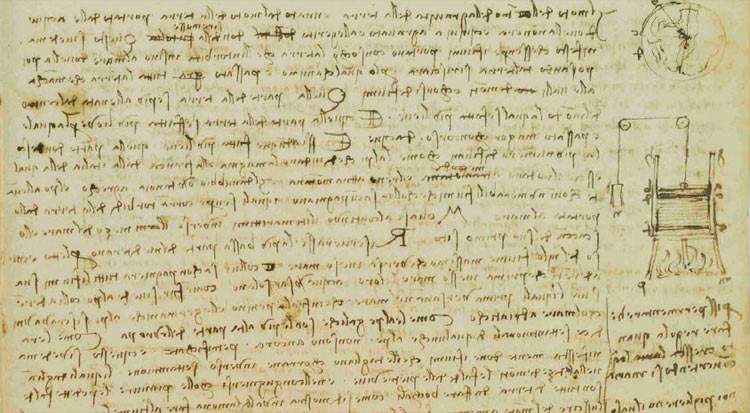

“We have discovered the birthplace of paleontology: it is in the Piacentino Apennines,” Baucon says. The result was achieved by comparing Leonardo da Vinci’s codices with the fossil record of the Piacentino. In particular, Baucon systematically studied Leonardo’s codices and found a possible match in a passage from the Codex Leicester, to be precise in folio 10v, which has long been the focus of Baucon’s attentions. In this passage Leonardo describes curious shapes in the stone, correctly interpreting them as ichnofossils, or fossilized traces of the movement of ancient animals. “It was an incredible thrill to discover that Leonardo had guessed the true nature of ichnofossils: these are the most difficult fossils to understand, just think that until the first half of the twentieth century scientists misinterpreted them as algae.” In the Codex Leicester, Leonardo also guessed at the organic nature of so-called “petrified shells,” the fossilized remains of ancient mollusks (Leonardo calls them “nichi”) that the artist’s contemporaries saw as inorganic curiosities. Five centuries before any scientist, Leonardo combined the two halves of paleontology (fossil remains and ichnofossils).

As for the location of Leonardo’s laboratory, Baucon and colleagues gave a precise answer to this question believe it was located in the vicinity of Castell’Arquato. The conclusion is dictated by the geographic and geological constraints imposed by Leonardo himself: in the late 15th century, the artist was in Milan working on the equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza, when peasants brought him fossil mollusks with perforations (ichnofossils), coming, as Leonardo attests, from the “montagnie of Parma and Piacentia.” Leonardo also says that between one layer and the next there are ichnofossils produced by marine worms, that is, in Leonardo’s words, “one can still find the gaits of the earthworms, which walked infra them when they were not yet dry.”

In the new study, Baucon and colleagues describe a new paleontological site(Pierfrancesco, a hamlet in the municipality of Gropparello) that is very rich precisely in ichnofossils of vermiform organisms. The site is a short distance from Castell’Arquato, where there are fossil mollusks with perforations. “Leonardo,” Baucon goes on to explain, “pointed to an area between Parma and Piacenza, mountainous, rich in fossil mollusks, and with two different types of ichnofossils, that is, perforations on shells and traces of vermiform organisms between the layers.” To achieve this result, no special technological means were needed, but a lot of perseverance and a bit of luck in reading the Leicester code.

Unfortunately, there are no drawings of fossils in the Leicester codex, although Leonardo deals extensively with the subject, but some depictions appear in Manuscript I of the Institut de France. According to Leonardo da Vinci, marine fossils were the remains of animals and evidence of the Earth’s changes, evidence that where there is now dry land there was once a sea (indeed, the artist considered those who thought they had ended up on the mountains as a result of the universal flood or celestial influences to be “ignorant”).

The study has not only historical but also paleontological importance. The discovery of Pierfrancesco’s new paleontological site sheds new light on the biodiversity of deep-sea ecosystems that, between 50 and 70 million years ago, characterized the Piacentine Apennines. In particular, the study describes how marine ecosystems responded to immense ecological disturbances, triggered by turbid currents capable of transporting cubic kilometers of sediment into the depths of the deep. In the words of Fabrizio Felletti, “Pierfrancesco’s rocks bear witness to turbid currents capable of moving cubic kilometers of sediment across the ocean floor for hundreds of kilometers.” Variations in oxygenation and/or nutrient content played a key role, underscoring the valuable balance that governs marine ecosystems.

“In a way, it was Leonardo da Vinci who brought me and my colleagues to Pierfrancesco,” Baucon concludes. “I like to think that our paleontological study picks up Leonardo’s intellectual legacy.” According to the scientists, the next step will be to disseminate to the general public the extraordinary ichnological diversity of the Piacenza Apennines, a place where history and science meet. The study has benefited from major funding from the University of Genoa and the CARIGE Foundation, which approved research projects focused on the study of the fossils that provided the inspiration for this work. Additional funding was provided by the Natural History Museum of Piacenza and the Piacenza Natural Science Society.

|

| This is where the fossils that Leonardo da Vinci mentioned in the Leicester Codex came from |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.