The four grotesque heads that Bernini had made for his carriage

The public recently saw them at the Caravaggio and Bernini exhibition held in two stages between 2019 and 2020 at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. They have only been exhibited twice in Italy: at Palazzo Strozzi in 1962, at the Italian Renaissance Bronzetti exhibition, and in Rome, in 1899, for theBernini Exhibition held that year at the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline Hill. Now, the four screaming grotesque heads by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) arrive on the market for the first time: Presenting them to potential buyers, with a 1.6 million euro request, is Flavio Gianassi FG Fine Art , which has chosen the prestigious stage of the Florence Biennale Internazionale dell’Antiquariato to give everyone a close look at the four heads, four bronze elements that were part of the personal carriage of a Bernini at the height of his success, and can be dated to a period between 1650 and 1655.

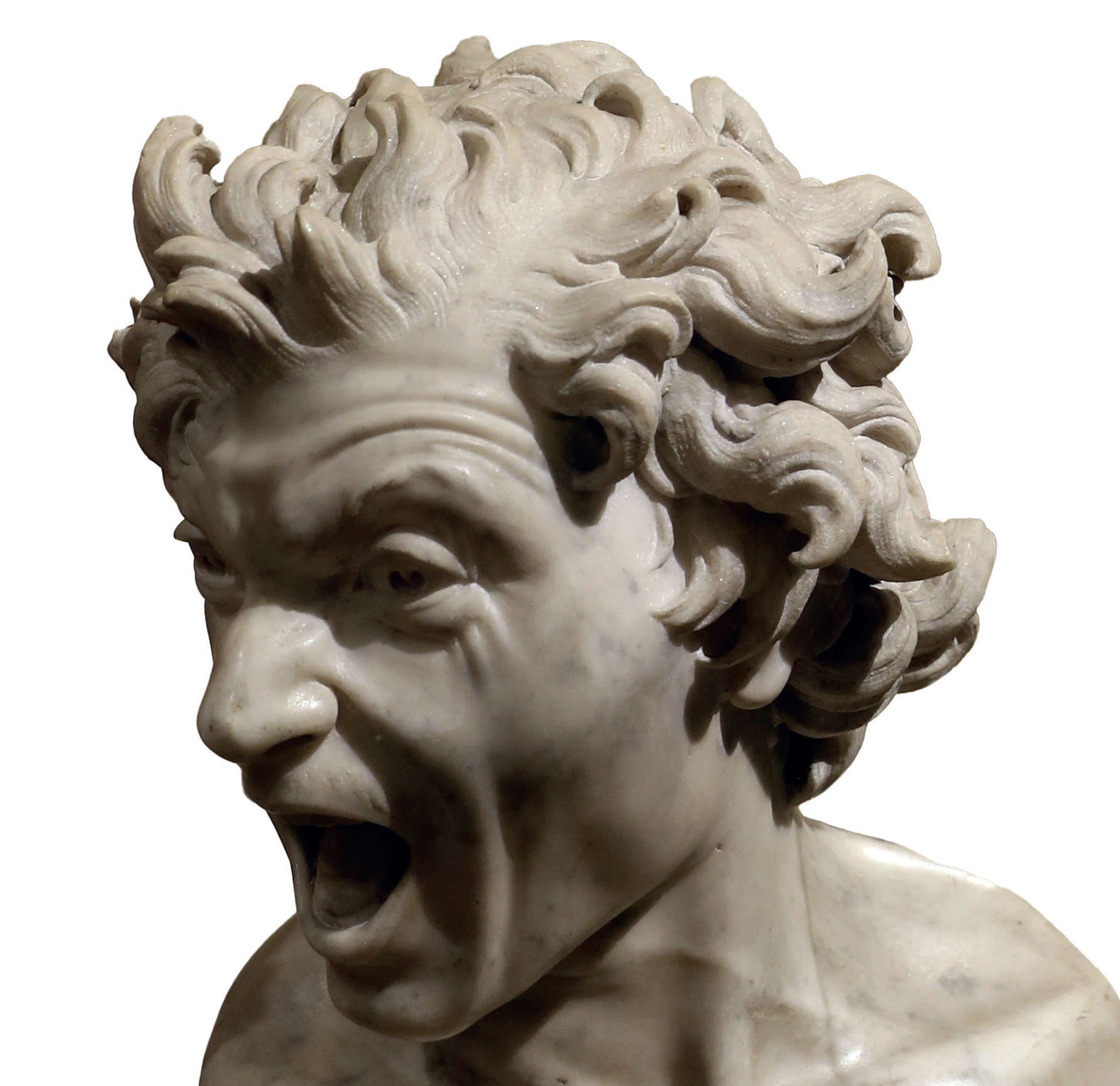

They were cast from the same model and are striking in their facial expressions: wide-open eyes, strongly arched eyebrows, a shouting mouth, the hair and beard divided into angular locks to express a movement of despair, but without having a naturalistic character: they are, if anything, to be seen as four caricature heads, of the grotesque genre, to be understood only as decoration. The attention to detail, even in size and applied decorative function, has been related to the open-mouthed feral head adorning the hilt of the sword of the Ares Ludovisi, added by Bernini. Their gilded monochrome is not a limitation to the quest for movement and drama, achieved through the ingenious use of light and shadow, curves and edges, which succeeds in making them almost alive. Finely executed, extravagant works, each equipped with an irregular hole in the nape of the neck (it served to accommodate the plumages in vogue at the time), they were originally made as side elements for Bernini’s personal carriage. It would be Bernini himself, at an unspecified time, who would remove them from the carriage to include them in his personal collection and place them, as the first inventory records, in the hall of the noble apartment of his palace on Via della Mercede together with a “portrait of Pope Urban the Eighth made of fired clay” and a “portrait of Card.l Borghese made of fired clay.” These are a group of sculptures, now mounted on pedestals of black Marquiña marble, which have always, uninterruptedly remained in the possession of the artist’s heirs until today.

It should be noted that family tradition remembered them as ornaments of the carriage used by Pope Innocent X, made at the inauguration of Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona on June 12, 1651, but in fact, thanks precisely to discoveries on inventories, it is now clear that they were cast by the artist for his carriage. However, their history, as mentioned, has always been linked to that of the Bernini family. After the sculptor’s death in November 1680, his personal collection passed to his son Paolo Valentino, who kept it in the residence at 11 Via della Mercede, in Rome’s Rione III Colonna, in which the artist had been living since 1641, the year in which he purchased the property from Marchesa Fulvia Naro. Valentino had been born in 1648 from Gian Lorenzo’s marriage to Caterina Tezio on May 15, 1639; he had also been a sculptor and had worked together with his father. In the inventory of 1681, the first made after the artist’s death, the sculptures are listed in the noble apartment as “four cast bronze Testine con li suoi piedi di pietra.” Even when the inheritance passed to Prospero, Bernini’s grandson and son of Paolo Valentino and Maria Laura Maccarani, of an ancient and noble Roman family, the collection remained in the palace on Via delle Mercede. As a direct descendant of Gian Lorenzo, he inherited the largest part of the collection, to which must be added the inheritance of his uncles Pietro Filippo and Francesco. Prospero had complied with the provisions of his grandfather’s will by having the “rinovatione” drawn up at intervals of twenty-five years, in 1706 and 1731. The 1706 deed records in the antechamber “four Testine di gettito di bronzo son li suoi piedi di pietra, quali erano li vasi della carrozza già descritta.” In the same inventory, moreover, appears a description of the “shed adjoining the dinette,” where there are still “Two carriages all with its bandinelle and with all the mute of said bandinelle, which were of the b.m. of the said Signor Cavaliere Giovanni Lorenzo, and for that matter very ancient, and old, which for the lapse of time both from before as for having been covered with scorruccio after the death of the said Signor Cavaliere have been worn out by the lords heirs, and there remain four metal knobs of a carriage, which have been gilded, and are preserved.”

In the 1756 inventory Prospero stated only briefly that nothing had changed and that all the statues and paintings remained as and where they were in 1731, thus not carrying out the practice required by the testamentary provisions. Prospero’s death was succeeded by his son, Mariano, who had a new inventory drawn up on August 12, 1771. Thanks to the latter, we know the arrangement of the rooms and works in the palace on Via della Mercede, where the four heads of Gian Lorenzo’s carriage were placed in the antechamber and described, in numbers 170-173, as “four Heads of Gilded Metal cast on the original model of Bernino with feet of White and Negro.” The document, drawn up by the junk dealer Stefano Sartori with the help of the painter Gaspare Scaramucci, not only gives the measurements of the works but also their attributions. Mariano, moreover, upon the death of his mother Ortenzia Manfroni inherited the palace on Via del Corso, while maintaining his residence on Via della Mercede. After Mariano’s death (1789) the inheritance passed to his son by first marriage Francesco, who on his death in 1841 left it, as documented, to his brother Prospero Junior, Mariano’s son by second marriage. The works are recorded in the inventory of November 9, 1841, present “in the room at the described with a fenestra on the street, called dé quadri” above a “small table of albuccio varnished red carved, and gilded with good gold with stone above of yellow, and black [...] four Mascheroni of gilded metal originals of the celebrated author Bernini, with bases of port venere.” In this succession the four bronzes, along with the most important works of the Bernini collection, moved from the palace on Via della Mercede to that on Via del Corso, where Prospero and his family had resided since 1816. On May 19, 1858, upon Prospero Bernini’s death, a new inventory was drawn up, this time at 151 Via del Corso, where in the bedroom, above “a small table of carved and gilded wood in stone above impellicciata di verde di ponsella” the four bronzetti described as “four small busts of gilded metal to good effect” were recorded.

When Prospero Bernini died, having no male heirs, the inheritance passed to Vincenzo Galletti, husband of his daughter Concetta Caterina, the last of the Berninis, who died in 1866. They are remembered in the 1899 guide to “the districts of Rome” as “four grotesque heads of metal, modeled by Bernini himself.” Of their children only Teresa Galletti survives, who married Augusto Giocondi, from whom was born Caterina Giocondi, who in turn married Francesco Forti in 1890. From these was born Carlo Forti, father of the present owners. Finally, on February 20, 1964, the last catalog and estimate of the paintings and sculptures owned by the Forti family and coming from the succession of Casa Giocondi, heir of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, was compiled by Giuliano Briganti. The original nucleus of Gian Lorenzo’s collection, as we can read in his will, included works made by him, but also others purchased and commissioned from other artists.

We have no idea what the ultimate meaning of the four heads was, assuming they had one and were not just a demonstration of Bernini genius. There are those who, at most, have associated them with the marginalia tradition, the deformed, frightening, or bizarre marginal figures of the upside-down world that provide a derisive but decorative commentary on the seriousness of earthly existence. In every way they would have had a sarcastic function on the sculptor’s carriage: they were probably meant to make explicit his position on everyday life, the position of those who either did not take themselves too seriously or did not take others seriously enough to deem them deserving of mocking shouts if they dared to look at the artist’s carriage.

Bernini sculpture has a long tradition of extravagant faces. As early as 1619, when Bernini was in his early twenties, we find the first example of an incisive and violent expression, such as never before realized in sculpture. TheDamned Soul, now preserved in the palace of the Spanish Embassy in Rome, is in fact the first face, disfigured by an almost feral scream, in which the marble is not from limitation to the work’s dynamism, depicting a young man, oppressed by torment, looking down, and making the audience share in his horrors. Although the subject is probably believed to be a faun, Rudolf Wittkower suggested that the work could have been worked in front of a mirror and thus may be a self-portrait. Similar drama animates Bernini’s aforementioned work on theAres Ludovisi: the Roman statue, it found in 1621, became part of the antiquities collection of the wealthy Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, who commissioned the very young Bernini to complete the work. Having finished the surface and remade the right foot, Bernini amused himself with the hilt’s screaming head, similar to the bronzes on his carriage.

It was not uncommon for sculptors to be called upon in Rome to create the often exuberant, sculptural and symbolic designs of official cars, and there are several documented inventions for such decorations by Bernini. The sculptor designed, for example, the ornamental figures for the carriage given by Pope Alexander VI to Queen Christina of Sweden in 1655, the invention of which is evidenced by the autograph drawing preserved at the Royal Library in Windsor, and probably, he also worked on the one intended for the king of Spain. It is only thanks to a drawing by Nicodemus Tessin the Younger (Stockholm, Nationalmuseum), derived in turn from a Bernini drawing, that we know the external design of the latter prestigious one, which has friezes with grotesque masks similar to bronzes at the corners. This suggests, as scholar Jennifer Montagu has noted, that Bernini found such motifs particularly suitable for use as decorations for these types of carriages.

The fact that as early as 1899 the sculptures were exhibited at the aforementioned 1899 Bernini Exhibition denotes the interest scholars have always had in these small sculptures. The 1899 exhibition, designed to celebrate the third centenary of the artist’s birth (1898), was a major event inaugurated on April 19, 1899 taken at the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome, and as an article in Civiltà Cattolica from that year recalls, the four heads were displayed in the middle of the Hall of the Horatii and Curiatii along with other sketches and bronzes by the artist. However, we owe the first scientific attribution of the bronzes to Stanislao Fraschetti, in his seminal monograph on Bernini, the first ever dedicated to the artist. In fact, he tells of a visit to the Giocondi house where “four gilded bronze masks are preserved, by Bernini’s hand [...] resting on a polychrome marble plinth. They have their faces contracted almost in a sense of portentous wonder,” and he adds that those little heads “have their hair shaped in the usual manner of the artist’s sketches, and that is, they almost preserve the imprint of the thumb and forefinger that formed the simple and united lock like a solid excrescence.”

It was not until about sixty years later, in 1961, that the works became visible to the general public again, as Bernini’s autographs, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, on the occasion of the exhibition Italian Bronze Statuettes, which was followed in the same year by the exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the following year by the exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, Italian Renaissance Bronzetti. John Pope Hennessy, in his 1963 article commenting on the V&A exhibition, while regretting that the Baroque section was not as rich as hoped, credited the curators with having succeeded in including the four gilded heads. The works have always been unanimously published as autographs since the first monograph on Bernini, and only Wittkower in 1981 hesitated to refer them to Bernini’s direct hand, based on the 1706 inventory that does not mention the author. An opinion, Wittkower’s, superseded by the later discovery of the 1681 inventory.

Today, therefore, a group of bronze works ends up on the market that demonstrate not only an important moment in Bernini’s career, but also what the artist had made for himself. They also denote a trait of his often excessive and eccentric personality. And they are also works that never left the close family circle. Natural, then, that there is curiosity and anticipation for a possible sale.

|

| The four grotesque heads that Bernini had made for his carriage |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.