Michelangelo’s declaration and energetic aversion to a veridical manner in portraying the likeness of a real person marks from the artistic point of view the most substantial break with the fifteenth-century bust-portrait: a break that is characterized on the historical-political level almost as a hiatus, because of the paucity of commissions for sculpted effigies in the period between the two Florentine republics, and during the subsequent reign of Alessandro de’ Medici [...]. Michelangelo’s reservations [...] were not so much directed against the portrait itself, or against the bust (the format par excellence of the genre, handed down from antiquity), but against the descriptive imitation of the casualness of individual appearance and external accidences in the anatomy of the person depicted: the wrinkled, sun-baked skin of Pietro Mellini, carved as if it were a cast impressed in soft matter by Benedetto da Maiano, his master in the art of the chisel, or the tumorous nose of that grandfather painted by Ghirlandaio, his master in the art of the brush [...].

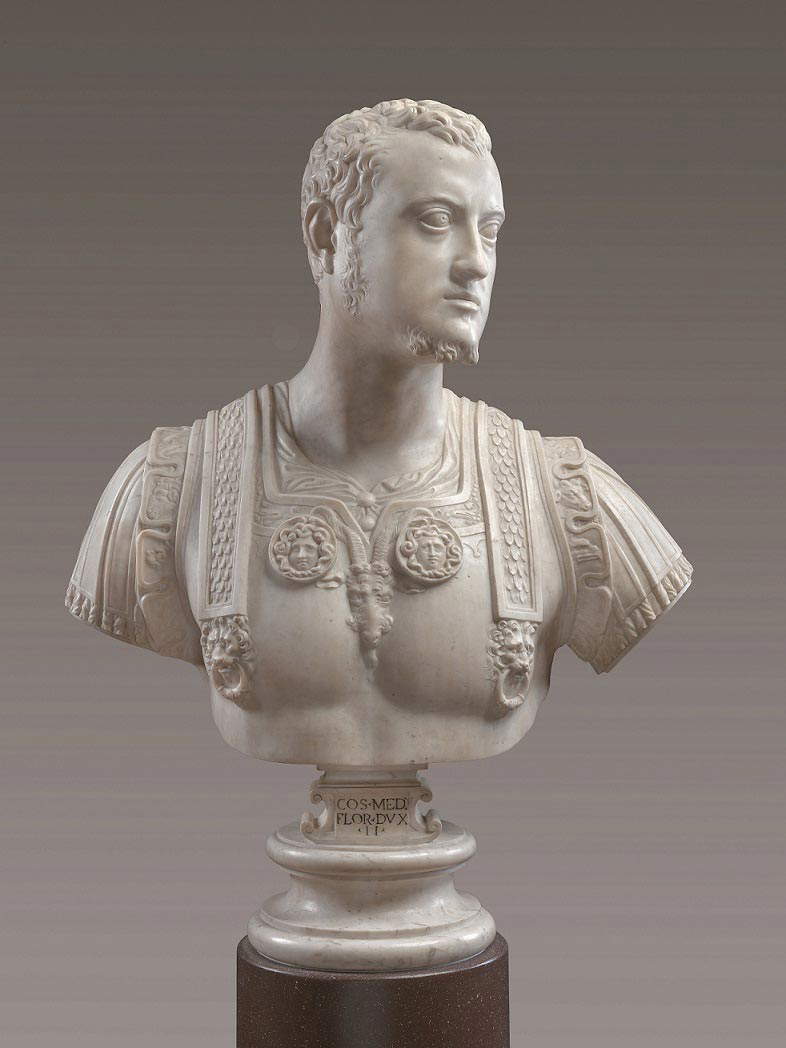

In the bust of Cosimo I about twenty-five years old, and still little bearded, sculpted by Baccio Bandinelli around 1544 we find the first attempt to meet the new demands of the courtly bust. In it the stylization of the face is evident, in keeping with the portraits painted in the same years by Pontormo and Bronzino. But more than by the head, the viewer’s attention is drawn to the rich iconographic apparatus displayed on the surface of the antique-style cuirass, with the large capricorn head (the duke’s personal sign) in front of the sternum, accompanied by two apotropaic discs with Medusa heads. The pair of lion protomes with rings in their jaws and the variety of zodiac signs on the cuirass complete the allegorical staging of the duke’s image.

An obvious reaction to the Bandinellian model should be seen in Benvenuto Cellini’s larger-than-natural bronze portrait of the duke, executed soon after his return from France, where with accentuated virtuosity the allegorical elements adorning the cuirass (incorporating, among other things, the Toson d’oro, of which Cosimo was awarded in 1545) are multiplied - in an overlay of compositional symmetries and asymmetries. At the same time, however, the artist again gives importance to the head, depicted in a decisive lateral movement, with the sinews of the neck tense, and the muscles of the forehead contracted in a concentrated and attentive expression. Insofar as it emerges from comparison with other portraits of the duke, Cellini “improves” on the truth especially with regard to the hair, described as thick, in clear contrast to the duke’s baldness visible elsewhere, which not only adds pride to the expression, but also perhaps has the value of alluding to his leonine character.

---

Eike D. Schmidt, Portraiture in Florentine Sculpture between Michelangelo and Pietro Tacca in Franca Falletti (ed.), Pietro Tacca. Carrara, Tuscany, the Great European Courts, exhibition catalog (Carrara, Centro Internazionale delle Arti Plastiche, May 5 to August 19, 2007), Mandragora, Florence, 2007, pp. 41-43

|

| Supercult. Eike Schmidt on Baccio Bandinelli |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.