Siena, finishes restoration of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Cross of Carmine

After three years of work, the restoration of the Cross of Carmine by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Siena, 1290 - 1348) in Siena ends, and it can finally make its way back to the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena after intervention directed and coordinated by the Regional Directorate for Museums of Tuscany of the Ministry of Culture. The restoration began in 2020, when the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena was part of the Regional Museums Directorate of Tuscany headed by Stefano Casciu, and over the three years of work has seen alternating directors and curators before concluding today in the autonomous institute headed by Axel Hémery. The Carmine Cross, after the intervention directed and coordinated by Stefano Casciu, curated by restorer Muriel Vervat and realized thanks to the generous contribution of the Friends of Florence association through a gift from The Giorgi Family Foundation, was presented today in the dedicated room of the Pinacoteca where it will remain on display in evidence until January 8, 2024. At the end of the temporary exhibition, the Cross of Carmine will then be relocated to Room 7 of the Pinacoteca, along with other works by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

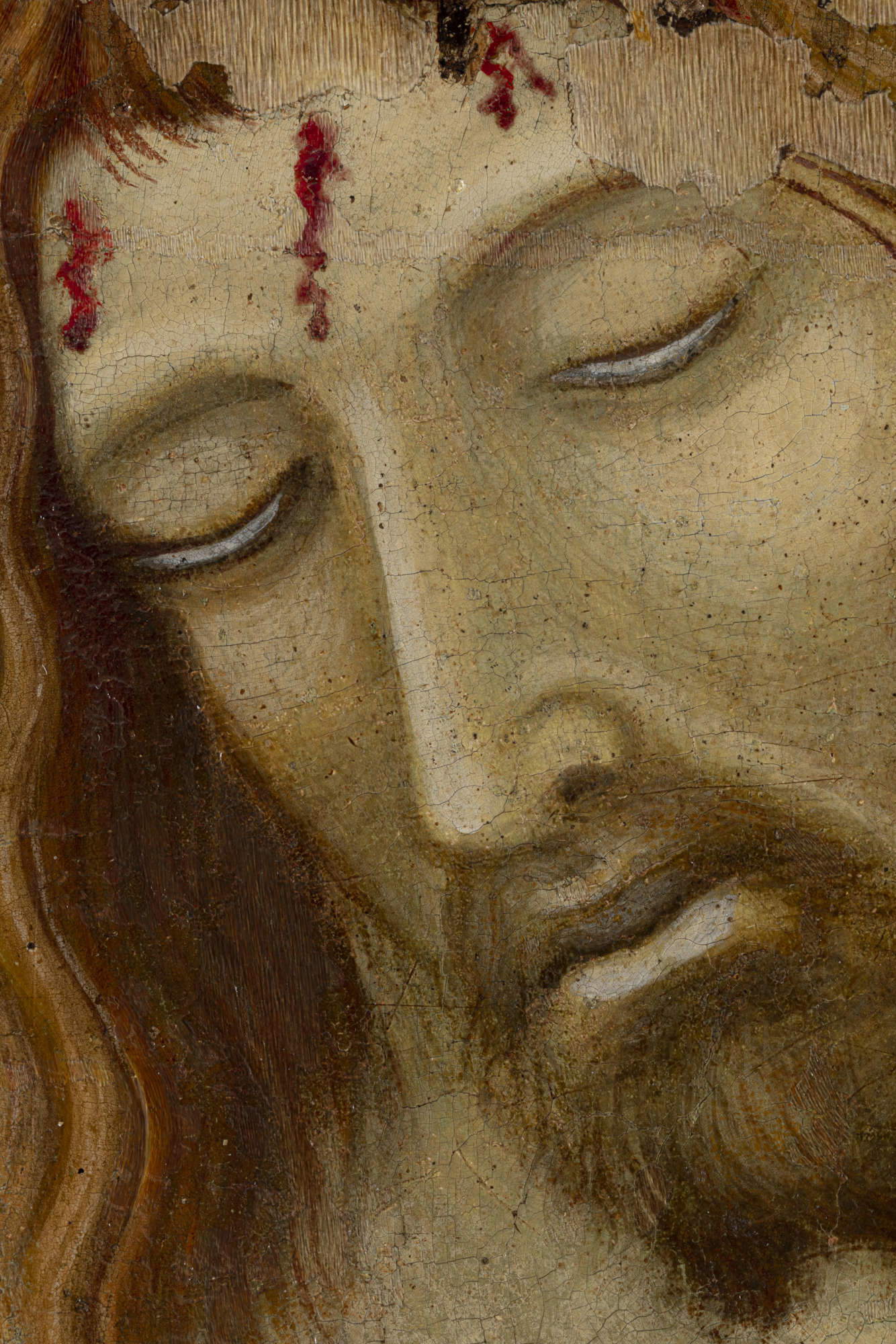

The monumental painted cross, which came from the convent of San Niccolò al Carmine, was deposited by the City of Siena with the Royal Institute of Fine Arts of Siena in 1862, thus becoming part of that original nucleus of works that make up the National Picture Gallery’s collection. Events relating to the history of the Carmine Convent allow us to assume that the cross was made around 1328-1330. In these years there are documented works of rebuilding of the church, financed also thanks to the participation of the Government of the Nine, which saw a modernization of the furnishings, with the realization of works such as the great Polyptych of the Carmelites by Ambrose’s brother Pietro, also preserved in the Pinacoteca (room 7). The dating is confirmed by the style: the work fits easily intoAmbrose’s early activity, being still closely related to Giottesque painting, but already showing the interests that would characterize the master’s more mature production and a refined taste in the elaborate punched decoration of the tabernacle and halo. The face of Christ, with a straight nose and elongated slit eyes, belongs to a physiognomic type that recurs in the figures of the frescoes in the chapter house of St. Francis.

In terms of structure, the work, although now missing some parts, fits into a context of crosses painted in Siena between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, marked by the complex carpentry work with starry polygon terminations and frame molding, in comparison with which Ambrose refines the Gothic canon of type.

His interest in observing reality already emerges in his choice to depict the wood grain of the cross, preferring this realistic detail to the more usual blue background. But the painter’s supreme skill in rendering naturalistic elements is clearly expressed in the figure of Christ. Theanatomy of the body is studied in volume, a softly shaded chiaroscuro delicately describing the muscular bands, effectively emphasizing certain points of shadow (in the abdomen and the hollow of the arms) in contrast to the light coloring of the complexion over which the bright red of the blood stands out powerfully. With a painting composed of subtle soft brushstrokes, Ambrogio Lorenzetti depicts the beard and brown hair that falls back framing the face, from whose expression we perceive the last moment of grief before resigning himself to death. The head is reclined forward, with a dramatic effect accentuated by therelief halo, and from below we see the full lips, but already veiled by a cyanotic glow, and the half-closed eyelids that give the figure a look of moving humanity.

The highly lacunose state of preservation has long conditioned the analysis of the work for which, in the first half of the twentieth century, various attributions were proposed: from reference to the early fifteenth century, by analogy with Taddeo di Bartolo’s cross for the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala (Pinacoteca, room 11), which has the same formal layout, to the juxtaposition to a generic Lorenzettian environment, then to Peter specifically. It was first Carlo Volpe, in 1951, who juxtaposed the cross with Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s name, a proposal unanimously accepted and reinforced in subsequent studies.

The cross of

The cross of

The

The

The

The The Christ

The ChristThe restoration

At the beginning of the work, the work had several conservation problems. During the nineteenth century, rainwater infiltration inside the Convent of the Carmine in Siena caused the painting to suffer significant and extensive color loss, but spared the face of Christ, which remained protected by the halo jutting out from the level of the cross. Prior to this intervention the work had already undergone restoration, carried out between 1953 and 1956 by the ICR in Rome under the direction of Cesare Brandi. That restoration brought out the original parts, thanks to the removal of later repainting, which was replaced by neutral backgrounds in underpainting. That restoration, aligned with the conservation theories of the time, largely still valid today, nevertheless made the reading of the work very fragmentary. The monographic exhibition on Ambrogio Lorenzetti, held in Siena between 2017 and 2018, brought to light the need to recover a better reading of the Cross, and Cristina Gnoni, then director of the Pinacoteca Nazionale, then proposed to Friends of Florence to fund the new intervention, designed by Muriel Vervat. The goal of the current restoration was the recovery of the original material, followed, however, by the chromatic reintegration of the gaps, for a unified and more enjoyable reading of the work.

The intervention was preceded by an articulated program of scientific investigations, by IFAC-CNR and ISPC-CNR of Florence, which not only provided valuable support for the restoration project, but also allowed a deeper understanding of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s sophisticated painting technique. The cross, which has a thickness of 4.5 cm and is made of poplar wood according to Tuscan tradition, is covered with a slipcloth and two layers of plaster, the first thicker and the second thinner, as per the ancient method also described by Cennino Cennini. The support has undergone alterations, and the work is mutilated of some key elements, such as the cymatium, the side terminals with the figures of the Sorrowful Ones, and the base of the support that probably featured Golgotha or Adam’s skull. The wide and elaborate gilt frame is the original one, characterized by a double molding ornamented along the edges with a fine pattern of intertwined, incised and painted arches. The stratigraphic analysis revealed, among other aspects, the manner in which the blood flowing from Christ’s wounds was applied, executed with two types of red: a basic, fuller-bodied one obtained from cinnabar, which is overlaid with a darker, brighter layer in red lacquer, obtained with kermes red, a precious pigment, more expensive than gold, which is a clear sign of a prominent patron.

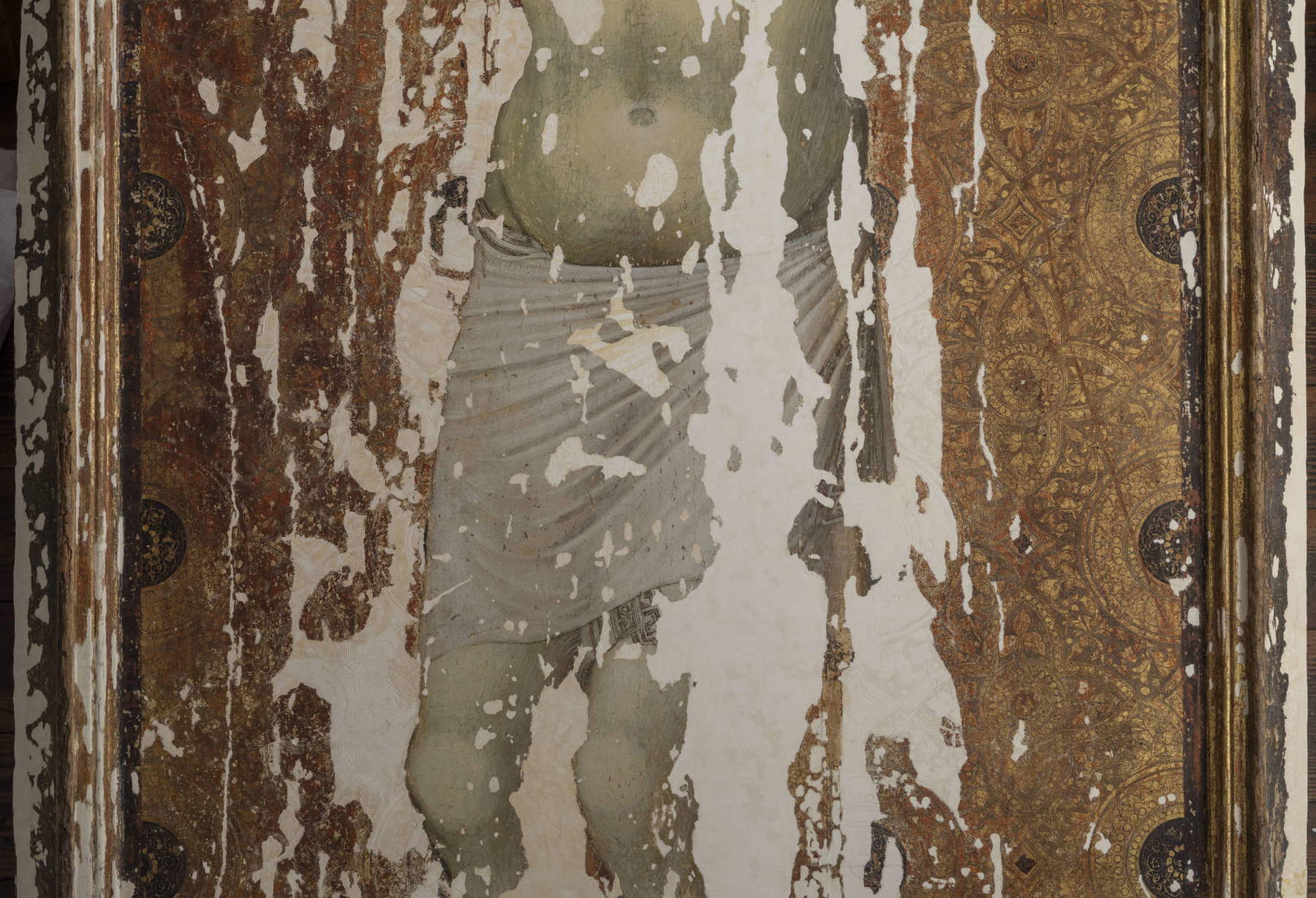

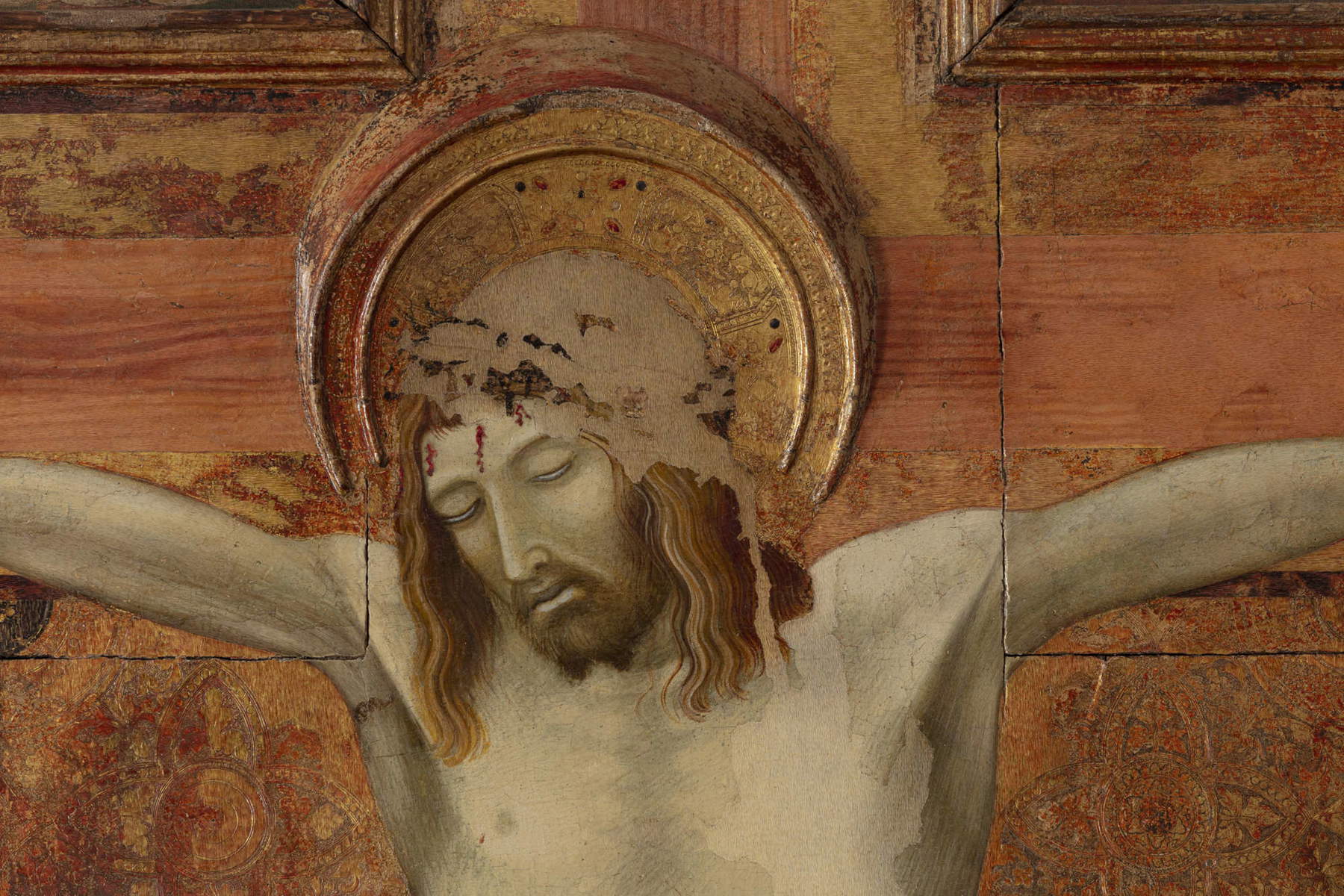

The intervention also was an important moment to conduct a more in-depth study of the execution technique and was accompanied by reflections on the conservation choices, particularly on the gold background and the large gaps that affected the body of Christ. The gold background of the cross, which imitates a richly ornamented fabric, is of important value because it presents not only a precious decoration, but also a sophisticated reflection by Ambrose on the diffusion of light. This value is less evident today because electric light allows one to enjoy sharply every detail of a work, but in Lorenzetti’s time, when the Cross was displayed in the church, illumination was provided only by natural light filtering through the windows, changing in intensity and direction according to the time of day, and by candle flames. These sources of light gave the pictorial material a vivid and changing luminosity that enhanced the plasticity of the painted anatomy of Christ’s body, where the points of greatest prominence are the shoulders and knees. And it was precisely this gilded background, made by the painter as a richly decorated fabric almost as if it were leather worked by burin with geometric figures probably made by compasses, that appeared very damaged. “Studying the complex design of the decoration,” Casciu and Vervat explain, “we realized that the figures had been made with a compass, forming symmetrical specular modules between the two sides of Christ’s body, and that it was possible to join the lost lines of the circles, engraving the new plaster with a compass as in ancient times, without forcing or inventing. At those points, to clearly distinguish the reintegrated parts from the original gilding, we first reproduced the red color of the bole with tempera, using the technique of chromatic selection, then completed the intervention by re-proposing the gilding with synthetic powdered gold, applied with the same selection technique.” The cleaning also brought to the surface, in a totally unexpected way, the painted wood of the actual cross on which Christ is nailed and which, with its pinkish hue and veining in naturalistic imitation of wood, creates a strong and studied contrast with the precious decoration of the geometric fabric of the background.

The other important methodological and executive decision to be made was the one concerning the treatment of the numerous gaps, a fundamental operation to give voice again to Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s poetic and artistic intention and to enhance and restore the narrative value of the original pictorial material. Many gaps on the figure of Christ could easily be closed, that is, brought down to the level of the surrounding original surface and integrated with the method of chromatic selection, simply restoring that lost continuity, where integrations posed no problems of interpretation. These connections, properly accompanied with a pictorial restoration intervention that respects the original, without making fakes or forcing, give back to the observer the possibility of an understanding of the painter’s original forms, composition and ideas, as well as of the preciousness and elegance of the final outcome desired by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, all aspects that before the restoration were difficult to appreciate.

Even the large gap that crosses Christ’s body vertically, characterized by a considerable loss of pictorial matter, was solved, with delicacy and respect for the original, by means of the technique of chromatic selection: the added color differs from the original painting by the lighter shade, but evokes, in the different areas, the hues of the complexion or those of the loincloth without inventing volumes or details that were definitively lost.

Only with regard to Christ’s hands was a reconstruction carried out that alludes more to the lost forms, but still using the technique of chromatic selection. “We believe in fact,” Casciu and Vervat conclude, “that for the importance of the overall legibility of the work and also of the religious and artistic message, in accordance also with today’s sensibility, this was a necessary intervention. Like all interventions of the restoration, in any case, these latest additions are fully recognizable and reversible.”

Detail of the

Detail of the Detail of the

Detail of the Detail of Christ’s loincloth

Detail of Christ’s loincloth Detail of the thong of Christ during the

Detail of the thong of Christ during the Detail of Christ’s loincloth

Detail of Christ’s loincloth Detail of the face of Christ

Detail of the face of Christ Detail of the face of Christ

Detail of the face of Christ Detail of the face of Christ

Detail of the face of Christ Detail of the face of Christ

Detail of the face of ChristThe statements

“The restoration of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Painted Cross by Ambrogio Lorenzetti at the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena, generously funded by the Friends of Florence to the Regional Directorate of Museums of Tuscany , now presents itself as a necessary and delicate restoration of a great masterpiece of the 14th century in Siena, but also as an important critical and methodological act,” says Stefano Casciu, Regional Director of Museums of Tuscany. “The intervention started from the work that was in the state consequent to the restoration of the 1950s, during which-according to methodological principles that were innovative at the time-all the ancient repainting had been removed, and the numerous and vast gaps had not been reintegrated, leaving the supporting wood or the underlying canvas visible. An idea of restoration that today we tend to overcome in order to give back to the image, and thus to the poetry of the work, a less fragmented reading, aiming at a unified rendering and an overall wider legibility, by means of reintegrations of both the preparation and the pictorial surface and part of the volumes and colors, though without any concession to arbitrary reconstructions. Thanks to the careful cleaning of the original, the splendid worked and gilded fabric of the background, with concentric patterns, the wood of the cross with its pinkish and naturalistic veins, and the sublime values of the body and face of Christ, rendered by Ambrose with subtle and intense technique, still clearly visible in the face, which fortunately has been preserved almost intact, have also re-emerged. A difficult but challenging restoration, conducted by Muriel Vervat with her well-known great sensitivity and expertise. My thanks, goes not only to her, but to all those who made important contributions to the study and documentation of the work and the restoration, and again to the donors, especially the Giorgi family.”

“In a lifetime of being a museum director, a restoration of this importance is more unique than rare,” says Axel Hémery, director of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. "What does the return of one of the Pinacoteca’s masterpieces, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s restored Cross, tell us about the history of taste? It teaches us that, today, since it is a very damaged work, we can no longer accept the appearance of a restoration that was exemplary for the taste of the 1950s. Today, while respecting the principles of restoration enunciated by Cesare Brandi himself who had organized its first intervention, we can at the same time honestly acknowledge the vicissitudes of history and restore life, movement, and meaning to Lorenzetti’s intentions thanks to the work of high precision and absolute fidelity to the painter performed by restorer Muriel Vervat. It was made possible by the support of the Friends of Florence and its president Simonetta Brandolini d’Adda. The long-standing operation was initiated and supervised by the director of the Museums of Tuscany, my friend Stefano Casciu, then in charge of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena, entrusted to the direction first of Cristina Gnoni and then of Elena Rossoni with the constant participation of the Pinacoteca’s restorative officer, Elena Pinzauti. To these forward-thinking people committed to the preservation of art go my warm thanks both institutionally and personally. To Muriel Vervat, who combines a deep knowledge of artistic techniques with a very sure hand and a faculty of visionary imagination tempered by healthy doubts, goes my admiration and gratitude."

“The restoration of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Cross of Carmine was an important project for our foundation because it allowed us to work again for the preservation of Siena’s heritage, the destination of so many study programs that, as Friends of Florence, we periodically organize for our supporters,” stresses Simonetta Brandolini d’Adda, president of Friends of Florence. “Siena has always been a city that fascinates all our benefactors. This latest intervention, which began in the midst of the pandemic, was truly a project of great satisfaction; to work alongside as donors the meticulous work of restorer Muriel Vervat, closely followed by the Director of Works Stefano Casciu and the Director of the Pinacoteca Nazionale Axel Hémery was a privilege for Friends of Florence. It allowed us to participate, step by step, in the conservative recovery of the masterpiece. It was a masterful work during which the sharing of choices and reflections between the restorer and the art historians was truly generative as it allowed us not only to return to enjoy the work in its incredible beauty, but also to learn new information about the technique and mastery of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, a true cornerstone of the Sienese Trecento. As President of Friends of Florence, I thank Stefano Casciu Regional Director Museums of Tuscany for wanting, initiating and directing the worksite, Axel Hémery current Director of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena for his willingness and attention that he has always offered us, Muriel Vervat for the great restoration work and all the professionals who have been involved in the project. Our heartfelt thanks also go to donors The Giorgi Family Foundation who chose to support the intervention, giving all of us and future generations the opportunity to enjoy the beauty of this great masterpiece.”

|

| Siena, finishes restoration of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Cross of Carmine |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.