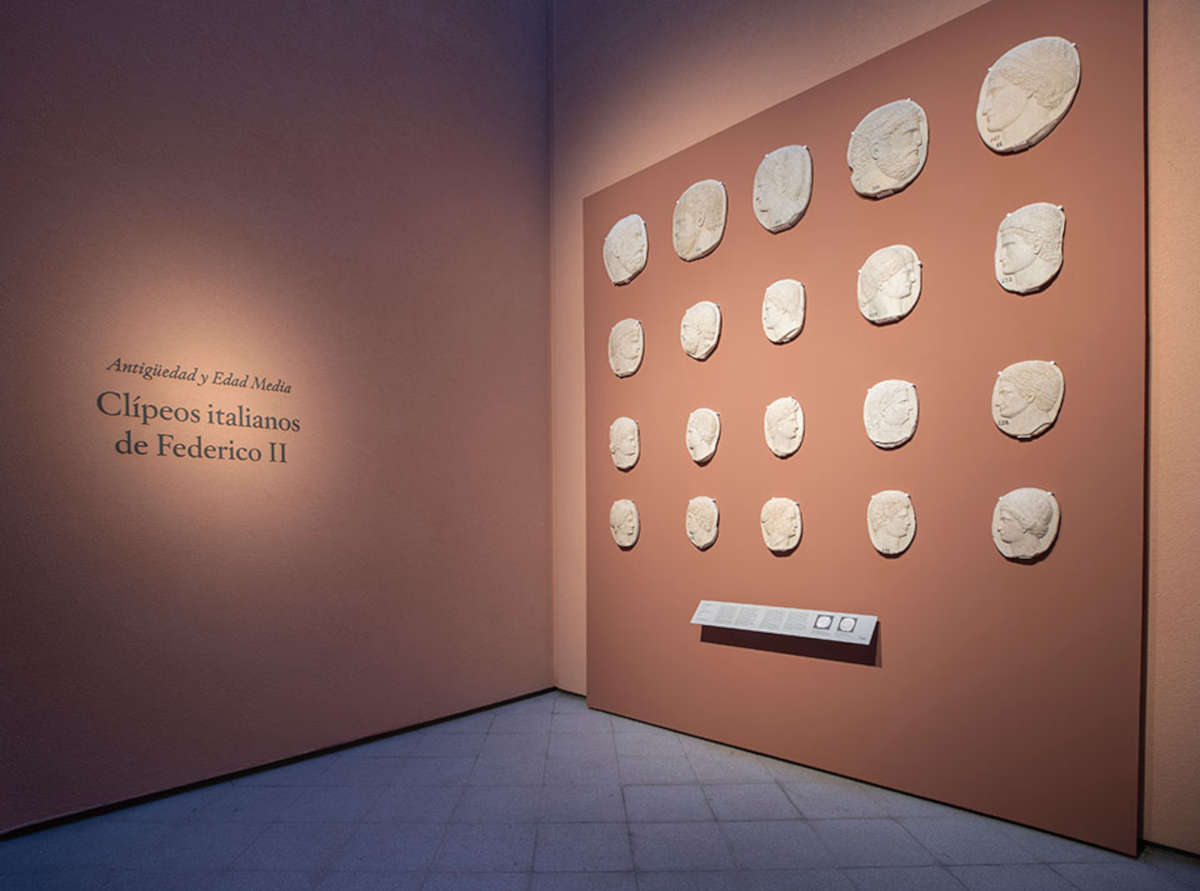

They would be from thetime of Frederick II some reliefs, twenty to be precise, preserved at the Prado Museum in Madrid and until recently thought to be modern works: according to the Spanish museum, which has conducted research on these twenty clipei, they would actually be what remains of a vanished monument that stood in Rome, on the Capitoline Hill. And their dating would have to go back a few centuries, to the time when Frederick II (1194-1250) reigned in southern Italy.

The news dates back to last March, but was not echoed in the Italian media. The clypeus, which were not on display, returned to scholarly attention following some work on the Villanueva building, the museum’s headquarters, specifically in the North Patio space. The work was aimed at creating a museographic intervention with sculptural works that had never been exhibited, and was carried out in collaboration with the OHLA Group, a company in the infrastructure sector .

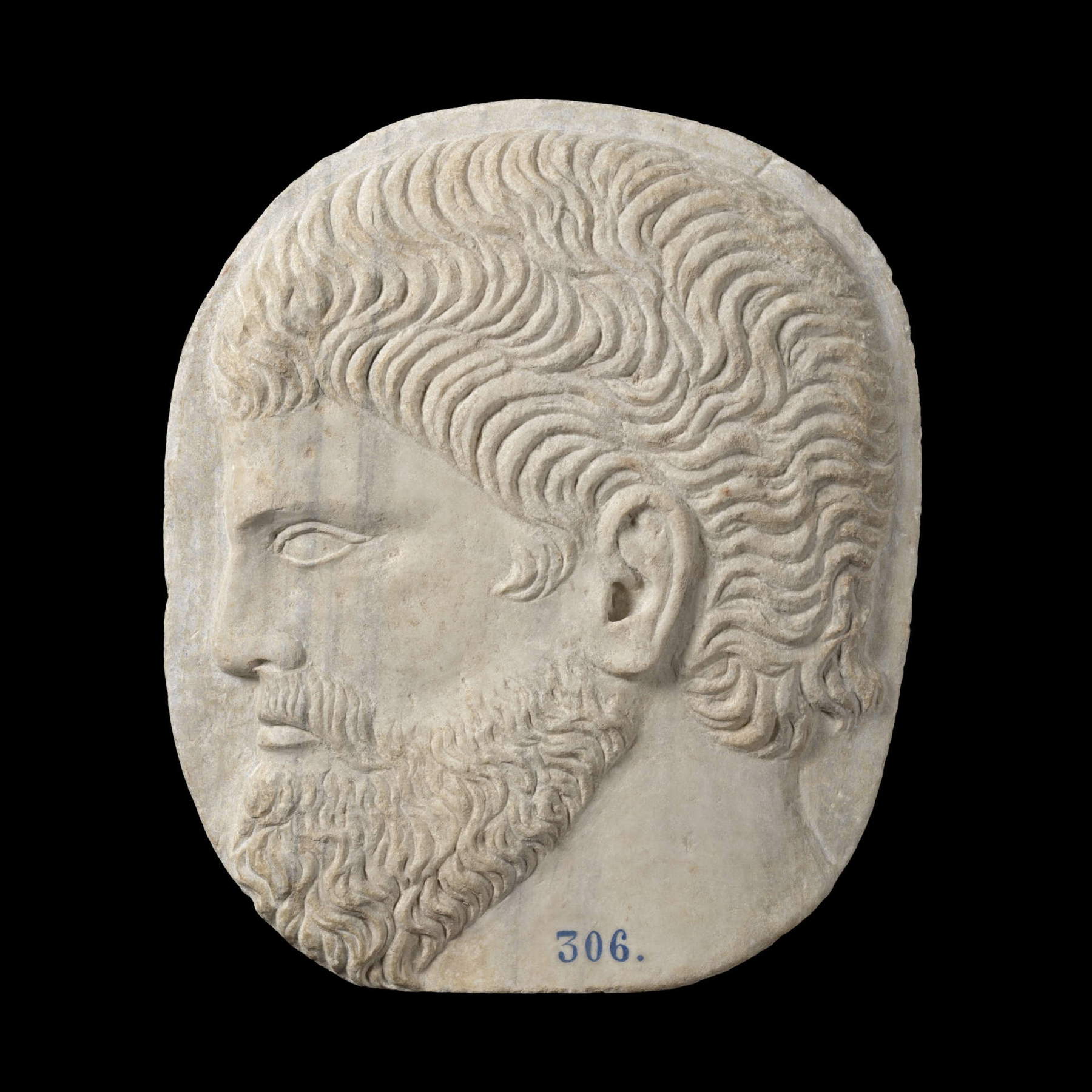

The reliefs are of different sizes and are all executed within irregular ovals. They are profile heads that fill virtually the entire sculptural surface, as is the case with cameos, with which these reliefs have a close relationship. Notable among these are the clipei of bearded figures, those wearing laurel wreaths, in the traditional manner of Roman emperors, and others in which various headdresses can be recognized, all of which have classical roots. Identification of the figures is not possible as they lack attributes or inscriptions. What is more, they are all united by the simplicity of execution of the work.

Coincidences with a number of pieces located in various parts of Italy have made it possible to propose for all of them a common origin within the so-called “Frederician” style, with a date around 1250. Very prominent in glyptics, this style was that developed during the time of Frederick II (1194-1250), king of Sicily and emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Grandson of Frederick Barbarossa, he was known as the stupor mundi (wonder of the world), and had intellectual interests in all disciplines. On his coins he depicted himself as a new Augustus and turned his gaze toward Antiquity, resulting in a major revival in the arts. Some of these reliefs, as mentioned above, have been linked to the decoration of a vanished monument on Rome’s Capitoline Hill, erected to house the remains of the carroccio, the symbolic military chariot that Frederick captured from the Lombard League at the Battle of Cortenuova, and which the ruler donated to Rome in 1237.

The pieces were all restored, and according to Manuel Arias, head of the Prado’s Sculpture Department, it was a laborious intervention because it was necessary to give aesthetic harmony and legibility to all the pieces that were in different conditions of preservation. In the past, the clypeus were considered to be from the modern period: some scholars dated them to the seventeenth century, others to the eighteenth century, then there was also talk of possible links with Renaissance works. Then, following a study in which the reliefs were compared with other sculptures, including some preserved in Italy (Arias spoke of reliefs preserved in Rome, Foligno, Genoa, and Spoleto), a chronology to the mid-13th century was proposed.

The reasons, Arias explained, are "very particular: in the middle of the 13th century a personage, Frederick II, who was reigning in Sicily, very bold, very singular in the medieval world, a man known as stupor mundi and who turned his gaze to the classical world, to an art in which the influences of Rome and Greece were mixed. These medallions have been classified as works from Frederick’s time because they do not fit the traditional patterns of Renaissance medallions: they are more summary, simpler, and then they have this oval, clypeus pattern related to cameos. We could say they are like giant marble cameos. The profile, the human figure fits very much in the field, there is almost no free space."

Arias compared the Prado’s clipei to a pair of reliefs preserved in Italy: one found at the monastery of Santa Francesca Romana in Tor de’ Specchi (Rome), the other at the Museum of Sant’Agostino in Genoa: both are very similar to the Spanish ones, and are identified as 13th-century Frederician clipei. We do not know exactly where the Prado clipei were originally located, but they were certainly part of an architectural decoration. In the past they were certainly part of the collection of Philip V of Spain-the reliefs are in fact marked with the Burgundian cross, the symbol of the ruler. They have certainly been in Spain since at least the early 18th century, but we do not know whether they were already on the Iberian Peninsula earlier, or arrived at that time. It is certain, however, that in the early eighteenth century the Spanish royals bought many works of art and antiquities in Italy, so it is possible that the purchases included these reliefs.

This ensemble would thus be an expression of the way antiquity was viewed even in medieval times: the iconographic models then coined continued to be a continuous point of reference in the thirteenth century. Those who want to see the clypeus should go to room 058B of the Prado: in fact, they are now on public display.

|

| Madrid, 20 poorly considered reliefs are now believed to be rare clipei from the time of Frederick II |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.