A unique depiction of an Islamic canopy in a 13th-century church, to be precise the church of Sant’Antonio in Polesine in Ferrara. Interpreting the unique iconography is young scholar Federica Gigante of Cambridge University, who published the results of her study in the February 2025 issue of Burlington Magazine. Federica Gigante’s article analyzes a unique 13th-century fresco located in the apse of the church of Sant’Antonio in Polesine in Ferrara, which had already been the subject of a study by Chiara Guerzi published in 2005, in which the iconography was first directed toward aerial canopies. According to Gigante, the canopy recalls Islamic portable tents, particularly those of al-Andalus (i.e., Spain under Islamic rule), woven in silk and gold, often captured by Christian armies during the Reconquista and later reused or sent as diplomatic gifts to Europe. This fresco may be the only surviving pictorial evidence of the practice of reusing valuable Islamic structures in a Christian context.

The use of Islamic textiles in medieval European churches is well documented. Many of these textiles, from both Western and Eastern Islam, were reused to wrap relics or the bodies of famous people. One example is the Shroud of Saint Josse, a Khurasan cloth from Emir Abu Mansur Bukhtakin (died 961), donated in 1134 and preserved to this day. Even Christian rulers were wrapped in Islamic silks, as evidenced by burials in the monastery of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas, Spain, which holds one of the largest collections of medieval Andalusian textiles.

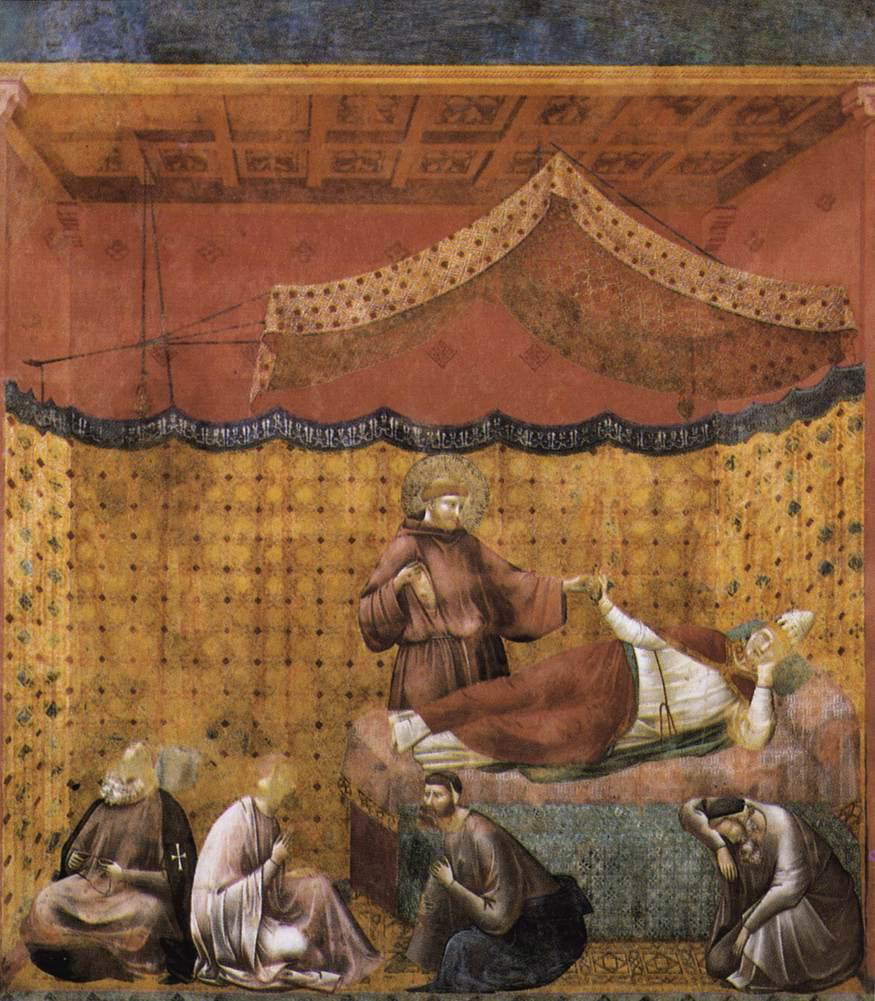

These textiles were also very present in 13th-14th century Italian pictorial representations. One example is Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Virgin and Child (1335-40) preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, where an Islamic carpet is painted under the feet of the Madonna, but the same can be said for Pietro Lorenzetti’s Birth of the Virgin at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena. In addition, Italian churches were often decorated with drapes of Islamic fabric. The Upper Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi itself contains frescoes by Giotto in which drapes with Arabic pseudo-calligraphy appear, inspired by real textiles from Andalusia.

The apse of the church of Sant’Antonio in Polesine features a rare example of pictorial decoration reproducing an Islamic tent, transformed into a canopy over the altar. The convent, founded in 1249 by Beatrice II d’Este, became a prestigious place thanks to the support of the powerful Este family. The decoration of the church began in the late 13th century and included a cycle of frescoes on the life of Christ, as well as painted drapery covering the lower part of the apse walls. In the 15th century, the fresco was partly covered with stories from the life of the Madonna and Jesus, but the drapery was still partially visible. While the attentions of critics have always focused on the later frescoes, those of Federica Gigante, a scholar of Islamic history (she had already distinguished herself last year with the discovery of a rare astrolabe in Verona), have instead mainly examined the curtain.

The fresco shows fabric with eight-pointed star motifs, inscribed in medallions with gold details, on a yellow background decorated with rhombuses. An upper and lower band contains pseudo-inscriptions in the Kufic style, first noted by Guerzi in his 2005 article, imitating inscriptions found on real Islamic textiles. The artists tried to make the cloth look realistic by painting bangs and folds, accentuating the optical illusion of the hanging fabric.

Above the cloth, in the lunettes of the side walls of the apse, a two-tiered conical structure is depicted, colored in yellow and red, with floral decorations and painted gems. Its resemblance to depictions of Islamic tents suggests that the painted canopy is a faithful reproduction of a real Islamic tent. The illusionistic effect is emphasized by the presence of a starry sky and painted birds between the folds of the tent, creating the impression of an open space under an outdoor tent.

The use of Kufic pseudo-inscriptions in the Sant’Antonio fresco in Polesine suggests that the fabric depicted was inspired by an authentic Islamic pattern. This type of stylized calligraphy was common in textiles produced in Andalusia, Anatolia, and Persia. A similar example is Don Felipe’s tunic, whose decoration matches a painted cloth in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi.

The blue and gold color of the fresco recalls imperial textiles from the Islamic and Byzantine worlds, such as the famous Blue Koran (9th-10th centuries) and the cloak of Emperor Henry II (11th century). The Fermo vestment, preserved in the Diocesan Museum in Fermo, an Islamic fabric made into a liturgical chasuble and attributed to St. Thomas Becket, has similar decoration and may have originally been a curtain or canopy, like the one painted in Ferrara.

Prominent among the few surviving fragments of Islamic curtains is the lid of a cushion by María de Almenar (13th century), woven in silk and gold with medallions and kufic pseudo-scriptures similar to the painting of St. Anthony in Polesine. Other examples include the mantle of Don Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada and the chasuble of Prince Philip of Castile, both woven in Andalusia in the 13th century.

Islamic tents were often objects of spoils of war, diplomatic gifts, or symbols of royal power. In 939, after the Battle of Simancas, Spain, King Ramiro II of León took a sumptuous tent from Caliph Abd al-Raḥmān III. In 1212, Alfonso VIII of Castile sent Pope Innocent III a silk canopy that had belonged to the Almohad caliph Muhammad al-Nāṣir, which was displayed in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Curtains were also donated as a symbol of prestige.Abbasid Hārūn al-Rashīd sent a tent to Charlemagne, and in 1338 the Mamluks exchanged silk tents with the Marinids. In 1576, Shah Tahmasp of Iran sent Sultan Murad III a ceremonial tent. In the West, tents were also offered as diplomatic gifts: in 1248, Louis IX of France sent a tent to Genghis Khan’s grandson Güyük Khan. In Ferrara, the monastery of St. Anthony in Polesine received numerous papal gifts, including precious fabrics, silks, and golds, which may have included an Andalusian tent, later painted as a canopy.

The fresco of St. Anthony in Polesine thus represents an exceptional testimony to the circulation and reuse of Islamic objects in medieval Europe. It is the only known example of a full-scale representation of an Islamic tent transformed into a canopy for a Christian altar. Its fidelity to Andalusian textile patterns suggests that the artist had access to a real tent or similar fabric. Not only that, given the presence on the apse of the church of nails and brackets that probably held hanging fabrics, it is entirely likely that a real Islamic tent was preserved in the church.

The church of St. Anthony in Polesine thus offers a unique window into the continuity and transformation of Islamic art and iconography in the medieval Christian world, demonstrating the importance of these artifacts as symbols of power, prestige, and sacredness.

|

| Islamic curtains in a 13th-century Ferrara fresco: young scholar interprets iconography |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.