Florence, 17th century Museo Galileo's precious celestial globe restored

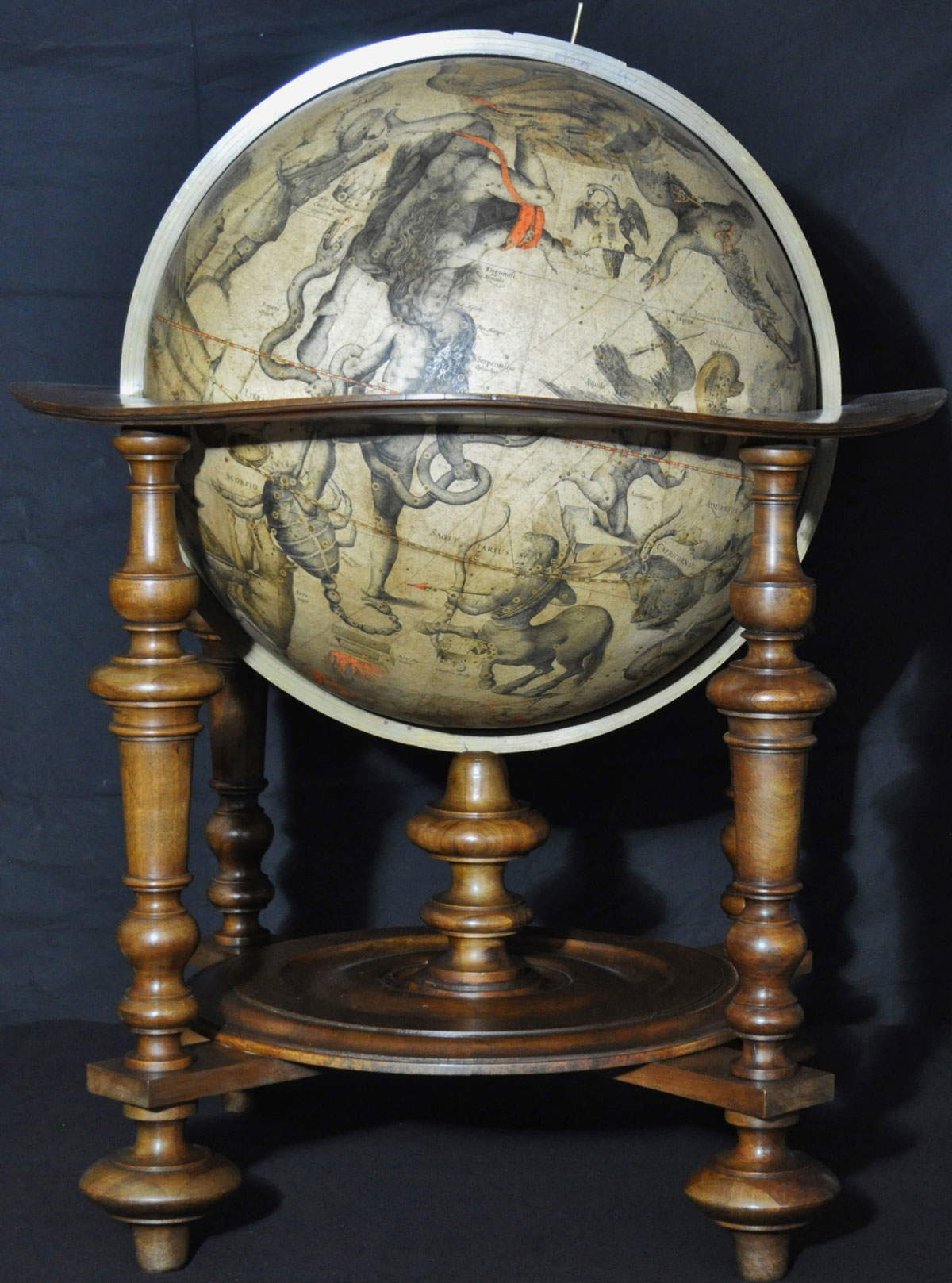

A major restoration of a valuable 17th-century celestial globe dedicated to the Lords of the United Provinces of Belgium, made by Jodocus Hondius Jr. and Adrian Veen in 1613, has been completed at the Museo Galileo in Florence. The six-month intervention was made possible by a contribution from Friends of Florence through a gift from Catharin Dalpino, who dedicated it to her father, Lt Col. Milton DalPino. The restoration was carried out by L’Officina del Restauro, under the scientific direction of Museo Galileo and the high supervision of the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the Metropolitan City of Florence and the Provinces of Pistoia and Prato.

Presented in 2020 at the 5th edition of the Friends of Florence Prize Salone dell’Arte e del Restauro, the project took off immediately after the donor was found: the restoration work on the Globe allowed the recovery of the full iconographic legibility of the work, restoring vividness to the colors and prints. They have also provided an opportunity to deepen knowledge of the execution technique.

“The Museum,” stresses Francesco Saverio Pavone, president of the Museum, “is happy and honored to have offered the opportunity for this important initiative, made possible not only through the action of the Friends of Florence association and the donor Catharin Dalpino, but also thanks to the restorers who were able, among other things, to provide us with unique insights into the work’s workmanship and its construction methods. I hope that such synergies between institutions and associations, together with the important expertise brought to bear by the Museum and the Superintendency, can be repeated in the future on other equally valuable works.”

“The Galileo Museum in Florence,” said Simonetta Brandolini d’Adda, president of Friends of Florence, “is a truly fascinating place: through the documents and instruments it preserves, it tells the story of how much the Tuscan court, at the time of the Medici and Lorraine families, was the promoter of modern science. ”Through its exhibition rooms, it tells us a story that is a fundamental part of our culture. The restoration of the Celestial Globe, the first project our foundation supported within the Museum, was a truly extraordinary conservation and discovery experience, and confirms how deeply art and science are linked. On behalf of Friends of Florence I would like to thank donor Catharin Dalpino for supporting the intervention, Museo Galileo for giving us the opportunity to safeguard a work that is a testimony to universal science, the Soprintendenza for guiding us through the project, and the restorers for conducting it with meticulous care."

Collaboration with the Museo Galileo will continue in the coming months in connection with the restoration of the Sala delle Carte Geografiche in the Palazzo Vecchio and Egnazio Danti’s Globo terrestre housed there. The Museum will provide the historical-scientific advice indispensable for the proper execution of the restoration work and will carry out the virtual reconstruction of the Hall according to Giorgio Vasari ’s original design and of the Globe, which has been heavily damaged by restoration and remodeling since the 16th century. A dedicated website will make it possible to explore the Globe and the entire Hall virtually.

The Globe

The Globe The globe

The globeThe Celestial Globe by Jodocus Hondius Jr. and Adrian Veen

Cartographic production experienced an intense fervor in the early seventeenth century. Geographical discoveries were the order of the day and meant the emergence of new markets and trade routes. Maps and globes were therefore sought-after objects that required constant updating. Therefore, the making and sale of these scientific instruments could bring substantial profits to their makers. A vital port in the prospects of political and economic independence of the United Provinces of the Netherlands from the Spanish crown, Amsterdam saw as many as three dynasties of cartographers competing with each other: the van Langren, the Hondt and the Blaeu. At the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, over a period of about six years, the competition resulted in the appearance of no less than seventeen editions of globes, each proclaimed, of course, to be superior to all the previous ones. In 1611, Joost de Hondt, or Hondius (1563-1612), having established preeminence over van Langren, began work on a pair of globes, celestial and terrestrial, 21 inches (53.5 cm) in diameter. After his death, the work was completed by his son Jodocus Hondius “the Younger” (1593-1629) and Adriaen Veen (d. 1572). The spindles of the celestial globe appeared in 1613, as indicated by a cartouche with a dedication to the lords of the Federated Provinces of Belgium.

The globe consists of 12 spindles, i.e., bands of paper with a maximum width of about 14 cm, divided into two parts each, and two circular caps. These cartographic elements are applied with millimeter precision to the surface of a sphere. The constellation figures are “illuminated,” that is, colored, after assembly and protected by a lacquer veil. The cartographic representation is of the “convex” type: that is, the constellations are shown as they would appear to a hypothetical observer placed outside the celestial sphere. This means that the figures and related asterisms appear mirror-like to how they are seen in the night sky. The representation also echoes the cartographic style of the rival Blaeu dynasty. All the constellations described by Claudius Ptolemy (2nd cent. AD) in the Almagest appear, with a few variations; for example, the chelicers of Scorpio are transformed into the independent zodiacal constellation Libra. Also noted are the constellations of the southern hemisphere plotted by explorer Frederick de Houtman (1571-1627). The positions of the stars north of the Tropic of Capricorn do not recover the traditional positions of the Almagest, but refer to the much more precise measurements of Tycho Brahe (1546-1601). The portrait of this Danish astronomer appears in a special cartouche, guaranteeing the scientific accuracy of the data used.

Only two celestial globes by Hondius and Veen from 1613 are currently undergoing restoration. Between 1992 and 1995, Sylvia Sumira worked on the badly deteriorated globe at the Scheepvaart Museum in Amsterdam. Lucia and Andrea Dori, on the other hand, restored the globe in the Museo Galileo. It is noteworthy that, except for the 53.5-cm diameter of the sphere that supports the cartography, the internal structure of the two globes is radically different: two hollow conjoined hemispheres in the former case, combined with an internal axis with a reinforcing cross; a single spherical shell in the case of the Museo Galileo, combined with a simple axis. The globe, as mentioned above, is dedicated to the Lords of the United Provinces of Belgium and shows stars observed by Tycho Brahe and Antarctic stars detected by Pietre Diercksz Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. The projection is convex and the constellation names are mostly in Latin. A portrait of Tycho Brahe is drawn below the constellation Ceto.

The construction technique of the Globe

In the case of the Museo Galileo’s celestial globe, the ball was constructed from a spherical form a few millimeters smaller in size and of material unknown to the restorers who conducted the work, on which, after the application of a probable release agent, as many as nineteen layers of paper were applied with protein glue. Once the papier-mâché was dry, an oval opening (12 centimeters long and 10 centimeters wide) was made and the material inside was removed by simply crushing it and letting it out of the previously caused opening. At this point the lathe-machined oak plank was inserted, to the ends of which brass pins were attached. The globe with its lid were then brought together with glue and inside the hole with a strip of paper, which investigations proved to be cotton-linen paper glued with animal glue.

Having been able to observe the interior, Lucia and Andrea Dori specify, “we verified the presence of book prints and precisely of an edition of a text by Paolo di Castro In Primam Infortiati Partem Commentaria. There are 12 paper spindles and two single-sheet caps and they were printed from copper plates engraved by burin. After the paper was glued, the constellations were colored with pigments and dyes with a binder probably based on gum arabic: reds based on minium, greens based on copper, and dyes and earths for the yellows and browns. Varnishing the globe with natural resins, shellac or other accentuated the saturation of the colors and prints and allowed them to be used by hand without damage to the surface. The meridian ring is brass and is missing the hour circle.” The horizon circle is not original and is mounted on a Dutch-type wooden base with four twisted columns and a central foot where the meridian rests.

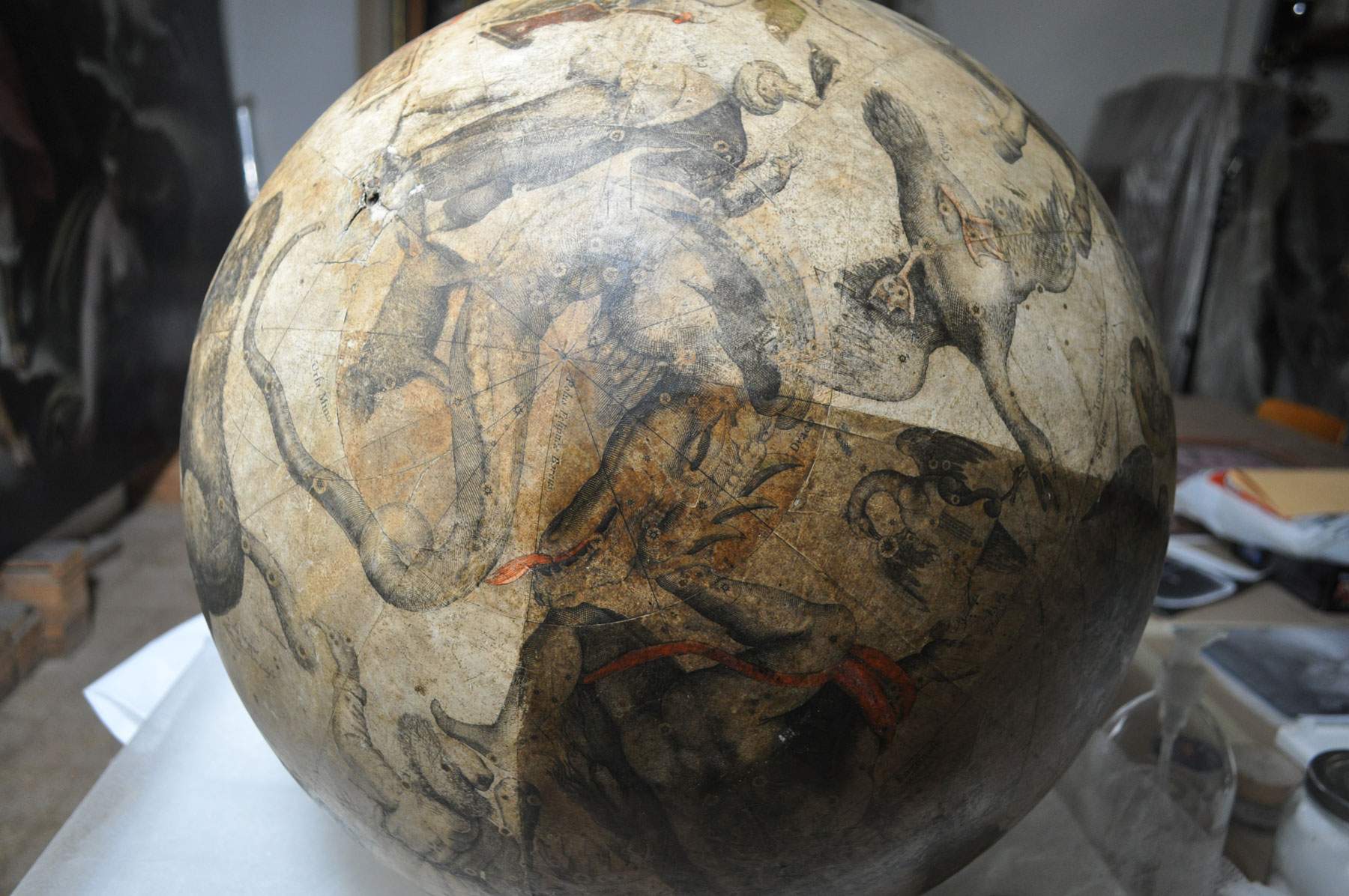

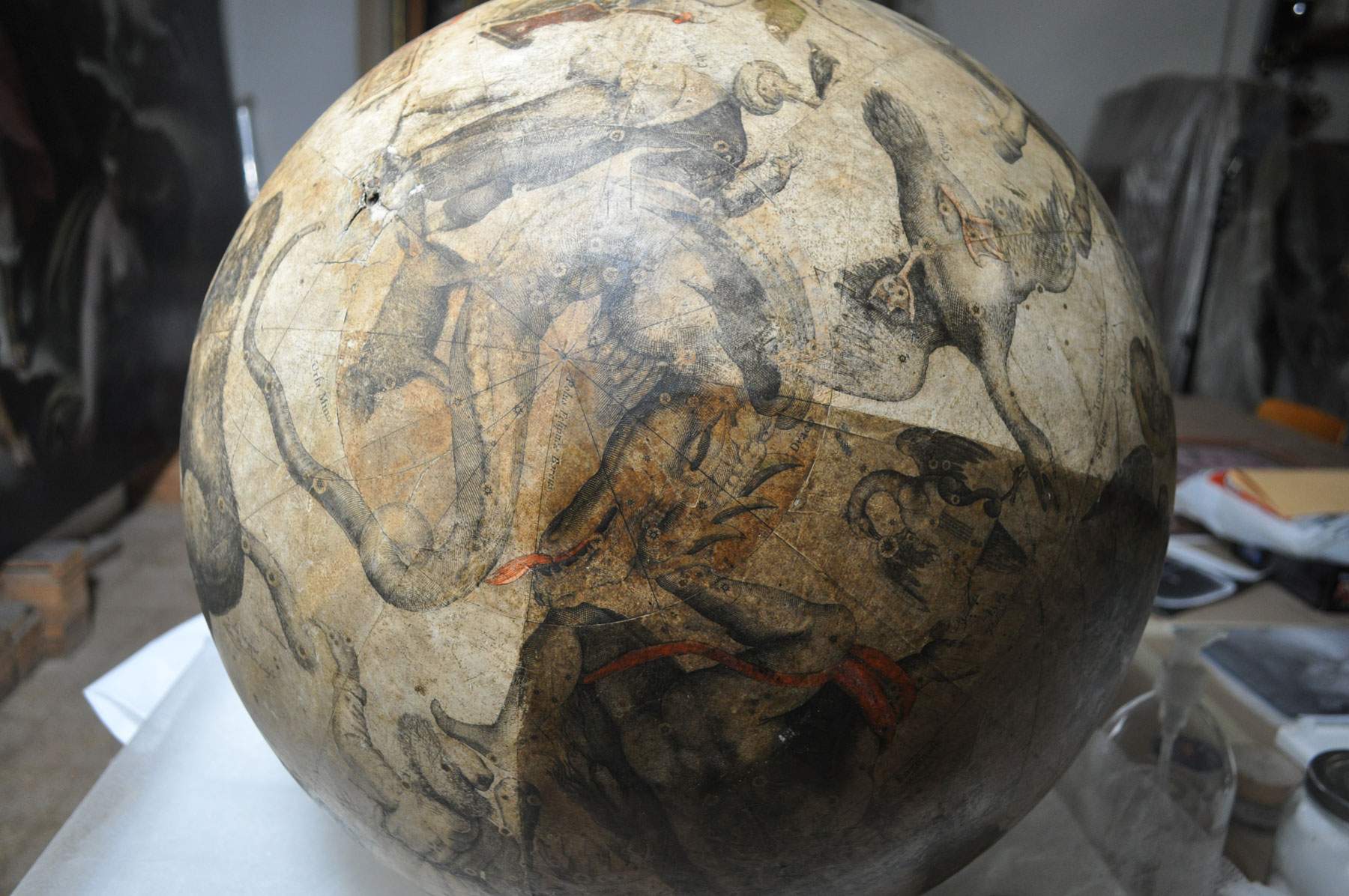

The state of preservation before restoration

The globe had problems essentially inherent in previous restorations. “The search for documentation,” explain the restorers, “unfortunately did not yield positive results, so we turned to observation and noninvasive diagnostic investigations. Ultraviolet fluorescence revealed the presence of non-fluorescent patinas probably due to pigmented glues and waxy varnishes with visible and disordered brushstrokes. False color infrared gave us information about the colors and their possible compositions while reflected infrared highlighted the print with no other overlays. But it was the X-ray that gave the most surprising results, confirming the construction of the whole sphere and finding no fractures or separations outside the visible opening at the south pole that we mentioned earlier. In fact, the X-ray revealed the outline of a branch with two wrappers at its ends whose contents we did not yet suspect.”

The surface of the globe, Lucia and Andrea Dori let Lucia and Andrea Dori know, had at least two depressions definitely due to mechanical trauma or accidental falls and some areas where rubbing and scratches were evident that highlighted the inside of the paper. In general, the alteration of the above materials made the prints and constellations barely legible, and their unevenness created areas of different coloration. The absorption of atmospheric particulates by the wax-based patinas made the surface of the paper darker and gloomier. And as is often the case with similar objects, the dirtiest and greying part was from the northern hemisphere while the southern hemisphere had more mechanical damage due precisely to its location. Highly visible at the south pole was the original paper cover held in place by a strip of darkened paper glued around its entire circumference, while the brass horizon rim showed no particular oxidation or major damage but only surface dirt and greasy impressions. The horizon band, made of wood like the base of a workmanship perhaps referable to the last century, very wavy due to the probable use of unseasoned wood assembled in an unorthodox manner, had certainly undergone previous maintenance.

Restoration

The Hondius and Veen globe was first subjected to a campaign of diagnostic investigations, after which the intervention was scheduled with the start of cleaning operations by performing preliminary tests to identify suitable solvents for the solubilization of substances on the paper surface. Underneath was an additional layer of surface deposit and protein glue residues that were removed to a safe threshold, so as not to deplete the papers, with methylcellulose in deionized water by brush and dab. The gentle and selective cleaning allowed the recovery of the original hues of the painted constellations of yellow, red, green, blue, and brown and the beauty of the prints where the use of the burin, with defined and clean mark, for engraving the copper plates is now evident.

During the cleaning, the yellow/brown repatination of the part of the original papier-mâché lid glued to the opening by a strip of paper was highlighted. Restorers performed a test removal of the paper strip with methylcellulose in deionized water and after the swelling had occurred, with scalpels and mechanical tools. “Under the paper,” Lucia and Andrea Dori explain, “we found the opening of the hole that was probably reopened in a previous restoration as we later verified. Together with the Works Management, in order to reposition the paper cover in a more consonant and precise way, it was decided to completely remove the paper strip and lift the cap to see the inside of the globe as well. With great surprise we then observed the sphere as we described in the section on construction technique and at the same time verified the nature and thickness of the layers that make up the paper mache. Another great surprise was the discovery of the twig of willow wood, inserted fresh so that it could be bent, at the ends of which were tied two paper straw wrappers that probably served to improve a depression in the paper. Obviously this confirmed that the reopening of the paper cover had been done during a restoration that we had no record of. After the decision was made to remove this twig from the interior because it was no longer useful and not part of the original structure, it was decided to open the straw paper wrappers to look for news about the intervention.”

Just inside the largest wrapper was found a folded piece of newspaper with the date December 24, 1942, a clue that dates the restoration certainly to those years. Folded along with the newspaper was a portion of an original wrapper of sewing threads of the brand Cucirini Cantoni Coats, a wrapper also used to form the wrapper. The interior of the globe now visible, and in particular the very precise position of the book papers inside, confirmed the hypothesis that the visible layer is the firstapplied on the sphere used for counterform: probably to have the same thickness of papier-mâché the makers will have calculated to the millimeter how and in what form to glue the various layers of paper material.

“In order to confirm the originality of the opening and the paper glued to the edges of the hole,” the professionals explain, “we made a sampling of the gray paper and glue that were chemically examined: the paper is an ancient cotton and linen-based paper glued with animal glue, and the glue is casein-based. Once the cleaning operations were finished, some paper lifts were stopped with 4% methylcellulose in deionized water and the few missing paper support was supplemented with the same glue and Japanese paper. The opening was closed by gluing the lid back by taking advantage of the same glue present on the thickness by simply moistening it and allowing it to reactivate; after drying, a putty made of cellulose powder, gesso, Klucel G in ethyl alcohol was applied to the perimeter joining the two parts, followed by integration with Japanese paper where necessary.”

The pictorial restoration, after saturating the inserts with the same material used for bonding, was carried out with watercolors in undertone for the reconstructed parts and for the constellation colors. Finally, the horizon and wooden base were gernicized, after which the horizon and wooden base were cleaned, further then disinfected.

|

| Florence, 17th century Museo Galileo's precious celestial globe restored |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.