England, Artemisia Gentileschi work discovered in Royal Collection's storerooms

According to art historians at the Royal Collection Trust, a painting that was recently rediscovered in the collection’s storerooms, and which has hitherto been known to have been misattributed, is said to be by Artemisia Gentileschi . The painting, depicting Susanna and the Old Men, was rediscovered as a result of the work of Royal Collection Trust curators, particularly former staff member and art historian Niko Munz, to trace paintings sold and scattered throughout Europe after the execution of King Charles I of England.

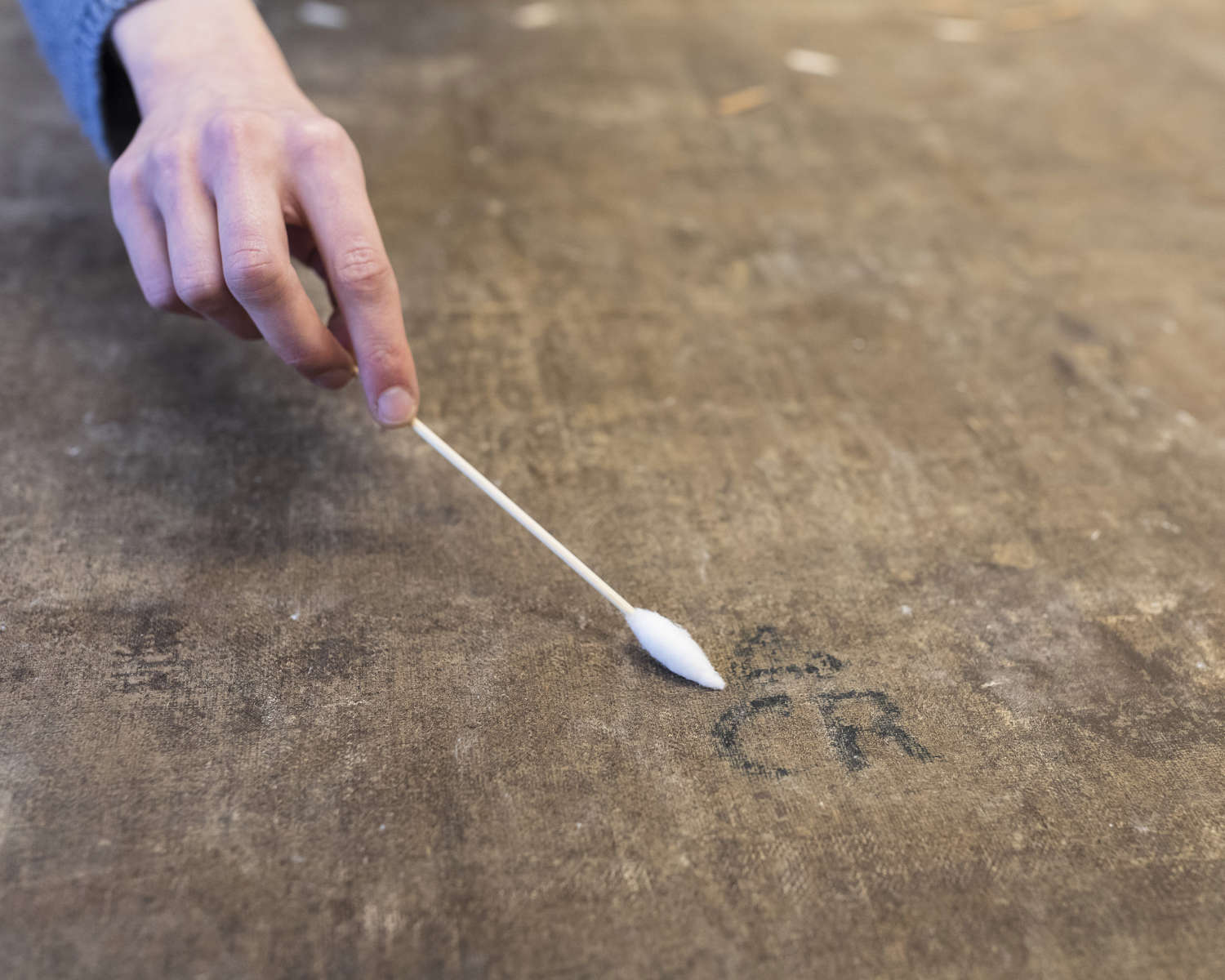

Seven of Artemisia’s paintings were recorded in Charles I’s inventories, but only the Self-Portrait was thought to survive today, while the others were thought to be lost. However, research allowed curators to match the description of Susanna and the Old Men with a painting that had been stored atHampton Court Palace for over 100 years, generically attributed to the “French School” and kept in poor condition. Later, during conservation treatment, the mark “CR” (“Carolus Rex”) was found on the back of the canvas, confirming that the painting was part of Charles I’s collection.

According to scholars, the rediscovered painting constitutes “a significant addition to Artemisia’s existing body of work” (so in a note) and “sheds new light on her creative process and the period she spent in London in the late 1730s,” when Artemisia worked alongside her father at the court of Charles I.

After careful restoration, the painting has been put on display for visitors to Windsor Castle. Shown alongside are the famous Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting (also known as “The Painting”), considered one of Artemisia’s greatest works, and Joseph and the Wife of Putifares by her father Orazio Gentileschi, painted during her stay in London. The three paintings form a new temporary exhibition in the Queen’s Drawing Room, taking their place alongside other Stuart masterpieces from the Royal Collection.

The rediscovered painting depicts the biblical story of Susanna, who is caught by two men while bathing in her garden. For refusing their advances, she faces a false charge of infidelity, punishable by death, but the affair will end with the recognition of her innocence. Artemisia has always placed great emphasis on Susanna’s vulnerability and discomfort as she tries to remove her body from the gaze of the two old men. It is a story to which Artemisia returned several times during her 40-year career: in fact, at least six of the artist’s compositions with the subject are known today. The story may have had particular resonance given her experience of sexual violence, as Artemisia was raped at the age of 17 by an artist in her father’s workshop and subjected to grueling interrogation and torture during her trial.

The painting’s history can be traced unbroken, with documents found in every century since its creation. It was commissioned by Enrichetta Maria of Bourbon-France, probably around 1638-9, during Artemisia’s brief period in London, when the artist assisted her elderly father in his work. The 1639 inventory of Abraham van der Doort, superintendent of the king’s paintings to Charles I, shows that the painting originally hung above a fireplace in the queen’s private room at Whitehall Palace, a room that Henrietta Maria used to eat, relax and receive small groups of officials.

The painting was returned to Charles II shortly after the Restoration in 1660 and is thought to have hung above a fireplace in Somerset House, residence of queens and consorts including Catherine of Braganza and Queen Anne. The painting was perhaps reattributed to the “French school” in the 18th century, a time of decline in Artemisia’s reputation. It was then moved to Kensington Palace, where it is depicted in a watercolor in the Queen’s Bedroom in 1819 leaning against a wall, suggesting that it was considered the work of a minor or unknown artist and not worthy of hanging. It was later moved to Hampton Court Palace, where it lost its frame at some point, and in 1862 was described as “in poor condition” and sent for restoration, at which point additional layers of varnish and overpainting were probably applied.

Since its rediscovery, the painting has undergone significant treatment by conservators at the Royal Collection Trust. The work included the painstaking removal of centuries of surface dirt, discolored varnish, and non-original layers of paint to reveal the original composition; removal of strips of canvas added to enlarge the painting sometime after its completion; reupholstering of the canvas; touching up old damage; and replacing the frame.

The

The

Analysis of the painting in conservation, they let the Royal Collection Trust know, confirmed the reattribution to Artemisia and provided insight into Artemisia’s working practice. The work is thought to have traveled with a stash of drawings that the artist used to create new compositions: in fact, conservators found that at least four parts of the painting had also been used in earlier works, including the heads of the Elders and the face of Susanna. Artemisia must have considered this Susanna particularly successful, as she reused elements of the figure in at least three versions of her later painting depicting Bathsheba at the Bath. Radiography (used to analyze aspects of a work not visible to the naked eye) and infrared reflectography (used to make the underlying design visible) also revealed Artemisia’s modifications to the composition, uncovering a large fountain painted at a later time.

“One of the most exciting parts of the story of this painting,” said Niko Munz, "is that it appears to have been commissioned by Queen Enrichetta Maria as her apartments were being redecorated for a royal birth. The Susanna was first hung above a new fireplace-probably installed at the same time as the painting-decorated with Henrietta Maria’s personal cipher ’HMR’ (’Henrietta Maria Regina’). It was definitely the queen’s painting."

Adelaide Izat, painting conservator at the Royal Collection Trust, said, "When it arrived in the studio, the Susanna was the most heavily overpainted canvas I had ever seen, its surface almost completely obscured. It was incredible to be involved in restoring the painting to its rightful place in the Royal Collection, allowing viewers to appreciate Artemisia’s art again for the first time in centuries."

The special exhibition of the works of Artemisia and Orazio Gentileschi is included in the tour of Windsor Castle through April 29, 2024. Windsor Castle is open to visitors Thursday through Monday, closed Tuesday and Wednesday.

|

| England, Artemisia Gentileschi work discovered in Royal Collection's storerooms |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.