Did the young Antonello da Messina work on the Triumph of Death in Palermo? The scholar's hypothesis

Could the young Antonello da Messina have been involved in the creation of the Triumph of Death in Palermo, one of the most renowned frescoes of the 15th century? This is the hypothesis of young art historian Riccardo Prinzivalli, a doctoral student in art history at the Academy of Fine Arts in Palermo who has just published a paper in the scientific journal Papireto to illustrate his idea.

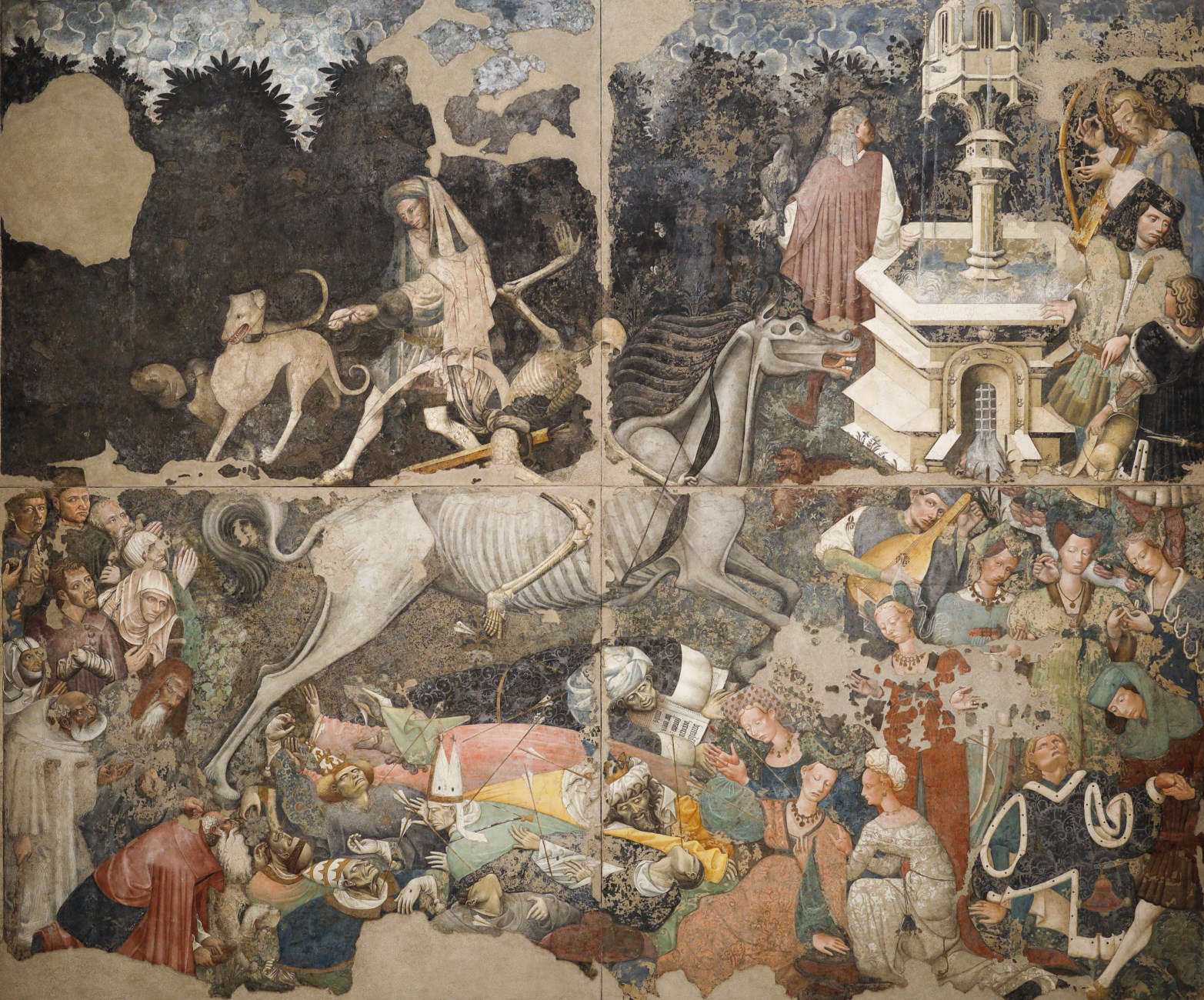

The ancient history of the fresco is quite well known (we discussed it in the last issue of Finestre sull’Arte Magazine in an article dedicated to the work): anciently, the fresco decorated the courtyard of Palazzo Sclafani, which in 1430 was transformed into a hospital (the Ospedale Grande e Nuovo). It was precisely as a result of the transformation of the ancient noble palace into a hospital that the painting was executed (perhaps around 1446, according to much of the criticism), which was probably part of a larger cycle on the theme of the “novissimi,” or the moments that await man at the end of earthly life (death, universal judgment, hell and heaven). During World War II, with the bombings that devastated Palermo, the fresco also suffered heavy damage, and it was detached admitted first to Palazzo Pretorio, was finally moved in 1954 to the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis, where it can still be seen today. However, we do not know who painted the work. Research by Riccardo Prinzivalli proposes linking this work to a possible collaboration between the still-unknown "Master of the Triumph of Death" and a young Antonello da Messina (Messina, c. 1430 - 1479), then at the beginning of his career.

The work depicts death as a skeleton on horseback, armed with bow and arrows, looming over a scene populated by characters of various social backgrounds: beggars, nobles, religious and allegorical figures. The background is a hortus conclusus, a symbolic garden that recalls both the lost Eden and the transience of life. The scene is a concentration of cultural, iconographic, and stylistic references ranging from the influence of Flemish and Burgundian painting to Italian art of the time. The depiction of figures such as Franciscan penitents, the poor, and the noble emphasizes a moral and religious message, perhaps highlighting the contrasts between earthly vanity and the inevitability of death. Of the work, however, a variety of readings have been given (refer to the article in our paper for more information).

One interesting aspect is the possible presence of two self-portraits in the fresco. Two figures on the left, a master and a young assistant, have been interpreted as the portraits of the authors themselves, a hypothesis that according to Prinzivalli, as will be seen, would strengthen the link between Antonello and the work. This detail, together with the stylistic quality of some of the figures, makes plausible in his view the involvement of the young painter from Messina, who at the time was assimilating stylistic influences from Neapolitan and Flemish masters.

The fresco’s cultural and stylistic influences.

The Triumph of Death reflects the visual culture of the 15th century, characterized by a complex interweaving of influences. “The most recent studies,” Prinzivalli writes in his paper, "have shown that the Triumph of Death was created in a peculiar cultural context that gravitated between Spain, Palermo and Naples, within thewithin the courts of Renato d’Anjou and Alfonso V, who had woven ties with Burgundy and Provence, giving rise to a refined and international environment in which the presence of artists such as Barthélemy d’Eyck and Jean Fouquet has been hypothesized. Roberto Longhi had thought of a Catalan mastery and advanced the name of Bernat Martorell, for his part Stefano Bottari observed similarities with the painting of the circle of Pisanello and the Ferrara workshop of Cosmé Tura and Francesco del Cossa. In comparing Colantonio’s Neapolitan training with that of the Master of the Triumph of Death, Evelina De Castro has detected a figurative culture common to the two masters, recognizable by the strong influence of Iberian and Flemish painting in mid of the 15th century, while pointing out clear stylistic differences between the two painters, of whom Colantonio seems more related to Flemish models while the Master of the Triumph, perhaps older, seems to look to the International Gothic style of the Iberian area. Nicole Reynaud, on the other hand, has recently proposed the name of Barthélémy d’Eyck, juxtaposing with the Triumph the images of the Angevin dukes depicted in the stained glass window of the north transept of Le Mans cathedral and the illuminated manuscript Livre des propriétés des choses."

Recent studies emphasize how the anonymous master’s painting technique was sophisticated and innovative. The preparatory sinopia drawing, dry-painting finishes, and the use of fine pigments such as azurite and cinnabar highlight an advanced technical approach. The combination of styles and techniques suggests a cosmopolitan workshop, capable of dialogue with major European artistic currents.

Similarities with other works of the period, such as the frescoes with the Stories of St. Bernadine in the La Grua Talamanca chapel in Palermo and the tablets of the Franciscan Blessed (works for which attribution to Antonello da Messina has been proposed by Fiorella Sricchia Santoro), reinforce the hypothesis of a stylistic continuity between the Master of the Triumph of Death and an artistic milieu linked to Franciscan patronage. In particular, the graphic rendering and arrangement of the figures in these works recall elements also present in Antonello da Messina’s early production.

The connection between Antonello and the Master of the Triumph of Death.

The possibility that Antonello collaborated with the Master of the Triumph of Death is not new: as early as 1981 Salvatore Tramontana aired the possibility of Antonello’s involvement in the undertaking. According to Prinzivalli, this idea finds support in various stylistic and documentary analyses. Born in Messina around 1430, Antonello trained in Naples under the influence of his master Colantonio, where he came into contact with Flemish, Franco-Burgundian and Provençal painting. This multicultural environment left a lasting imprint on his style, characterized by attention to detail and refined luministic rendering.

The link with the Triumph of Death could be explained by Antonello’s geographical and cultural proximity to the Palermo environment. There are meanwhile, according to Prinzivalli, historical tangents: in fact, Vasari wrote that Antonello was in Palermo, news of which we have no certain verification but which had already been considered plausible by Ferdinando Bologna, according to whom the young Antonello must have seen the Triumph of Death while it was still being executed, remaining influenced by it. “Bologna identifies in the realistic passages of the fresco those from which the Messina artist must have drawn the most vivid impressions,” Prinzivalli writes, “as in the lower left with the beggars, where he senses to a greater extent a connection with Colantonio’s first phase, asserting that the person who made the face of the blind man with the camauro must have seen the Neapolitan painter’s San Girolamo. A connection that the scholar points to by virtue of the links with the Burgundian-Provençal component of which Neapolitan art of the time was imbued.” Also according to Bologna, the place where Burgundian and Catalan figurative culture met was the Naples of Colantonio’s early activity, where Antonello da Messina had trained (the scholar, however, believed that the unknown master came from Spain, particularly from the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, and was in contact with the culture of Bernat Martorell).

“Colantonio’s and Antonello’s early works,” Prinzivalli writes, “are often juxtaposed with those of foreign artists whose presence in Naples is not yet certain, despite the various clues that suggest it, such as the surprising ancestry of some of these paintings with Neapolitan ones.” Among these works, Prinzivalli identifies Colantonio’s St. Jerome and St. Francis Delivering the Rule , and the Triptych of the Annunciation attributed to Barthélemy d’Eyck and made for the cathedral in Aix-en-Provence. The characteristics of the latter painting, in particular, would have been “avidly assimilated by Colantonio’s painting, including the graphic rendering of human figures, objects, and environments,” while in Antonello “they appear sensitized to formal synthesis and to the perspective and luministic innovations emerging in Italy, in particular those matured by Piero della Francesca and the Florentine and Roman experiences of Jean Fouquet.”

An example of this phase of Antonello’s work would be the Reading Virgin in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan, the attribution of which is nevertheless debated. According to Prinzivalli, however, it would be a relevant work to find similarities with the figures of the beggars of the Triumph and the nuns of the La Grua Talamanca chapel fresco: comparing the works, the young scholar writes, “one can see how the type of the faces and the rendering of the drapery in the clothes, soft and well outlined, with curved folds, not angular, immediately refers to the Virgin’s headdress and her thin and expressive face with the particular cut of the eyes and the slightly drooping eyelids, including the features of the faces and the garments of the crown-holding angels placed at the sides. In both works, the bodies and faces are well-proportioned, incredibly expressive, and stylistically in keeping with each other and with the experiences of contemporary central southern painting. This juxtaposition seems similarly possible in the likenesses of the characters depicted in the la Grua Talamanca chapel, in the Franciscan Blesseds and among the beggars of the Triumph, in which we also find relationships in the three-quarter poses and especially in the adherence of the graphic sign and stylistic features that can identify the young master.” The overall effect, Prinzivalli argues, “gives an unmistakable sense of humanity to the faces and gazes of the characters, rendered in the various works with familiar, non-idealized attitudes and features, whether in quiet poses or in pitiful and sorrowful ones, placing the viewer in a special relationship with the work.”

Similar comparisons, in the scholar’s opinion, could be advanced with regard to the draperies of the clothes, which in the Franciscan Blessed present a striking affinity with the representations of the beggars in the Triumph (according to Prinzivalli, the beggars were made by the same painter active in Santa Maria di Gesù, and then later finished in tempera by the master who painted the rest of the work), or the hands, an element often rendered by Antonello in a singular way (in the first phase of his career they are stretched unrealistically, which would denote the influence of Flemish, Franco-Burgundian, and Provençal works).

A particularly suggestive element concerns Antonello da Messina’s possible self-portrait. A forensic analysis conducted in 2021 by Chantal Milani compared the face of the young painter depicted in the Triumph of Death with the famous Portrait of a Man preserved at the National Gallery in London. The results, according to Prinzivalli, suggest a moderate compatibility between the two faces, indicating that they may indeed represent the same person. Although this is not conclusive evidence, “it is certainly unlikely,” Prinzivalli writes, “that this similarity between the two figures could only be the result of extraordinary chance, and it is nonetheless a truly surprising result and one that cannot be overlooked when one considers that there is a possibility that the two faces being compared depict the same subject while they could be anyone. Adding to these conclusions the documentary evidence on the London self-portrait and that on the Palermo frescoes exhibited in this study strengthens the hypothesis and increases the probability that those faces, already at first glance so similar despite the different pictorial language, are of the same person.”

A unique masterpiece (and Antonello’s role).

The Triumph of Death represents a unicum in 15th-century Sicilian painting, an extraordinary synthesis of cultural and artistic influences. The work reflects the dialogue between different traditions, from Flemish painting to international Gothic through the early manifestations of the Italian Renaissance. Antonello da Messina’s involvement may add a new dimension to the understanding of this masterpiece.

If Antonello had indeed been a collaborator of the Master of the Triumph of Death, this episode would represent a fundamental stage in the painter’s training, marking the starting point for a career that would make him one of the protagonists of the Italian Renaissance. The fresco, in turn, emerges as the product of an international workshop, capable of blending tradition and innovation in a work that continues to exert unchanged fascination. Who knows if the mystery about the author will ever be unraveled: what is certain is that to take the path of unraveling will also require studying the directions indicated by Prinzivalli.

|

| Did the young Antonello da Messina work on the Triumph of Death in Palermo? The scholar's hypothesis |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.