Cimabue’s gold backgrounds? They were not always made with real gold leaf: this is the finding of a research team led by the Institute of Chemical Sciences and Technologies “Giulio Natta” (Scitec) of the National Research Council (CNR) and the Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna, in collaboration with the University degli Studi di Perugia and the University of Antwerp (Belgium), which subjected Cimabue’s Maestà preserved in the church of Santa Maria dei Servi in Bologna to rigorous examination (the results were published in the scientific journal Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry).

Instead of expensive gold leaf, Cimabue used in this case a mixture composed of metallic silver powder and orpimentum (a yellow pigment “resembling gold,” as Cennino Cennini had called it in chapter XLVII of his Libro dell’Arte, the first treatise on painting in the vernacular, composed at the end of the 14th century). This particular mixture had the advantage of imitating gold very well and being less expensive, but the disadvantage was that over time it was bound to darken and lose its luster. The famous Majesty of Santa Maria dei Servi, datable to a period between 1280 and 1285, is precisely among the works affected by this darkening process. The browning, revealed Letizia Monico, a CNR-Scitec researcher and first author of the article, is primarily attributable to humidity, and this phenomenon can worsen if the painting is exposed to light.

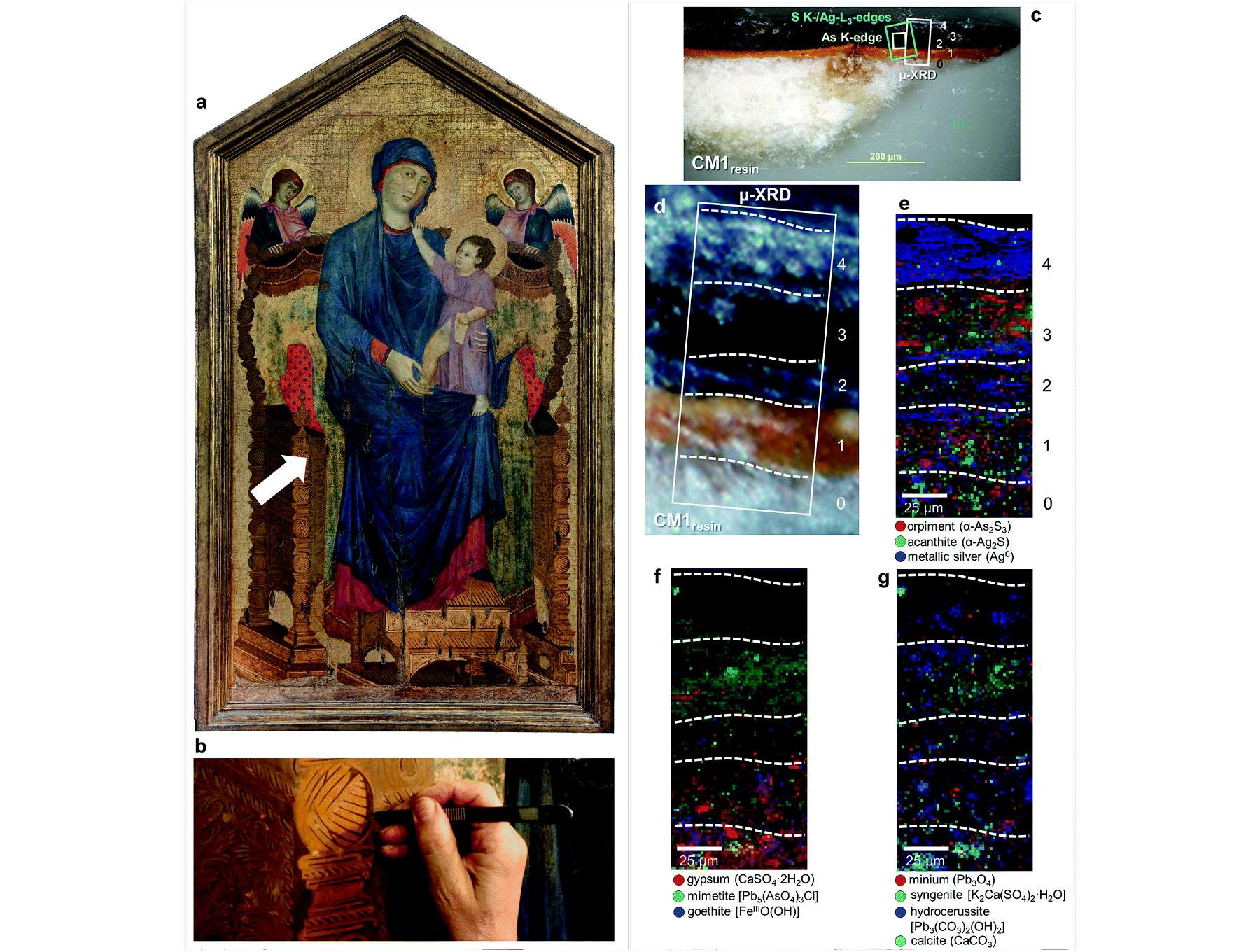

To obtain this scientific result, which is fundamental for the development of preventive conservation strategies for the work, a couple of micro-fragments carefully taken from darkened backgrounds of the Cimabuesque altarpiece were analyzed. The investigation was carried out by both laboratory-based vibrational microspectroscopy methods and techniques employing X-ray sources at the European synchrotron infrastructure ESRF (Grenoble, France) and the German national synchrotron PETRA III-DESY (Hamburg, Germany). In order to perform the analysis, micro-samples of the size of about 600-700 x 200-300 micrometers were taken. In particular, Letizia Monico explained to Finestre sull’Arte, “the micro-samples (analyzed in the form of stratigraphic sections) were studied by means of micro-analytical techniques employing sources of different nature (from IR radiation to X-ray radiation). It should be noted that these analytical investigations showed that the use of gold leaf was limited to only some areas of the work (such as the halo of the Virgin and Child and part of the background).” On the contrary, Monico further explains, “faux gold leaf” was instead used in other places, namely “at some of the decorations of the Throne of the Majesty.”

Cimabue was not the only one to use this preparation: it would also have been used, for example, by Pietro Lorenzetti, as shown by a study published in 2017. In fact, gilding characterizes many paintings made by famous masters of Italian sacred art in the late Middle Ages, such as Cimabue himself, Giotto, Duccio di Buoninsegna, and the aforementioned Pietro Lorenzetti. Gold, a symbol of royalty and devotion to God, was used in leaf to embellish backgrounds and decorative details. However, the NRC explains, because of its high cost its use was generally limited to the creation of the most precious details, such as haloes.

“Micro-analyses carried out at the synchrotron,” Monico further said, “allowed us to show that the darkening is due to the formation of silver sulfide, a black compound, which, to be clear, is the same material responsible for the blackening of many objects or jewelry made of silver. The chemical transformation, promoted by ’exposure to moisture and/or light, is accompanied by the formation of additional whitish degradation compounds, such as sulfates and arsenates.” To get further feedback, the paper says, micro-samples from the painting were compared with other samples taken from models that were artificially aged, and it was thus possible to establish that the alterations on some pigments to which the yellow orpiment is comparable are due to environmental agents acting on those very pigments. And again, the alteration of the gilding on the Majesty of the Servants occurred at two times, probably before and after the application of the oil-based varnish currently on the painting.

“The study of the painting,” adds Aldo Romani, associate professor at the University of Perugia, and co-author of the paper, “was supplemented with investigations of artificially aged tempera paint specimens, prepared using a mixture of orpiment and metallic silver, very similar to that identified in the ’faux gold’ decorations of the throne of Cimabue’s La Maestà. The results show that the original orpiment (chemically an arsenic trisulfide) by reaction with metallic silver is transformed into silver sulfide and arsenic oxides under conditions of high percentage relative humidity and/or in the presence of light.”

“The analysis of both the painting and laboratory pictorial specimens, with investigation techniques that are complementary to each other and characterized by high specificity, sensitivity and lateral resolution,” says Silvia Prati, associate professor at Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna, and other corresponding author of the work along with Monico, “has allowed us to understand the origin and evolution of complex degradation processes. This approach can then be successfully exploited to examine works of art executed with a technique similar to that of Cimabue and suffering from similar conservation problems.”

Thus, it was concluded that two factors should be acted upon to mitigate and slow the progress of the darkening process of the Majesty: exposing the painting to percentage relative humidity levels of no more than about 30 percent and maintaining lighting at the standard values expected for light-sensitive painting materials.

“At the moment,” Monico concludes, “we plan to continue to further study the problem of darkening on the same painting, supplementing it with further studies in the laboratory. Certainly the same strategy of analysis can also be applied to the study of other works made with a technique similar to that found in the Cimabue painting we analyzed.”

Pictured: (a) Photograph of the Maestà di Santa Maria dei Servi (ca. 1280-1285; tempera and gold on panel; Bologna, Santa Maria dei Servi) before the 2015 restoration (white arrow indicates sampling area). (b) Detail image of the sampling point of sample CM1. (c) Micrograph of CM1 resin cross sections taken with visible light (magnification: 200 ×) and (d) Corresponding detail image in which SR μ-XRD mapping was performed. (e-g) SR μ-XRD composite images of the identified crystalline phases [map size ( v × h ): 140 × 75 μm 2 ; step size ( v × h ): 1.5 × 1.5 μm 2; exp. time: 1 s per pixel; energy: 21 keV] (see Fig. S1 † for a selection of XRD patterns). In (c) the yellow and cyan rectangles show the areas where SR μ-XRF/μ-XANES surveys were performed, while the numbers indicate the painting stratigraphy.

|

| Cimabue did not always use gold in his paintings: here is the preparation that imitated it |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.