According to an American study, Leonardo experimented with gravity. A century before Galileo

Leonardo da Vinci pondered the laws of gravity and would have even conducted physical experiments on the acceleration of falling objects. The hypothesis, which would assign Leonardo a role as a forerunner of Galileo Galilei, was formulated by three scholars, Morteza Gharib (professor of aeronautics at the California Institute of Technology), Chris Roh (professor of biological and environmental engineering at Cornell University) and Flavio Noca (professor of aerodynamics at the Graduate School of Applied Sciences in Geneva). The theory was formulated in a paper published in Leonardo, a journal devoted to the relationship between science and art, published by MIT Press.

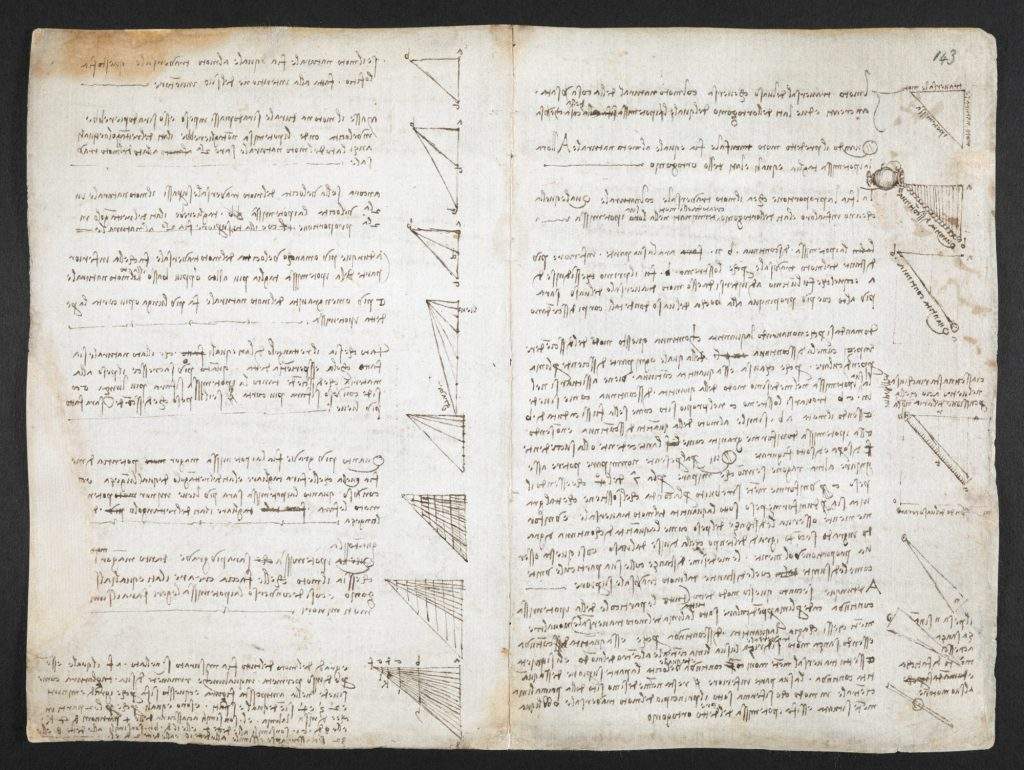

“Leonardo noted,” theabstract reads, “that if a vase pouring water moves transversely, imitating the trajectory of a vertically falling object, it generates a right-angled triangle (as in orthogonal) with cathetes of equal length, composed of falling material aligning diagonally (forming the hypotenuse) and the trajectory of the vase forming one of the cathetes.” Scholars refer to folio 143 of the Arundel Codex, preserved in the British Library, where they see an illustration of the vase from which the water falls. On the hypotenuse Leonardo writes the phrase “Equatione di Moti,” noting the equivalence of the two orthogonal motions, one operated by gravity and the other prescribed by the experimenter.

Professor Gharib, first author of the scientific article, told the New York Times that he learned of Leonardo’s gravity experiments while reviewing an online version of the Arundel Codex. This is a collection of notes compiled between 1478 and 1518, that is, between the ages of 26 and 66. The drawings and texts found in the Arundel Codex cover many topics in the fields of art and science. The item that caught Gharib’s attention is what he calls “a mysterious triangle” near the top of folio 143. Its strangeness lies in the way Leonardo’s sketch shows a jug pouring water from its spout, drawn together with a series of circles that formed the hypotenuse of the right triangle already mentioned in the article’sabstract . Gharib used a computer program to flip over the triangle and adjacent areas of writing. Suddenly, the static image seemed to come to life, as the scholar told the U.S. newspaper, “I could see the movement, I could see it pouring.” According to Gharib, this image would reveal Leonardo’s early experiment.

The effects of gravity are generally seen as the falling of something downward: one especially remembers the “gravi” experiment that Galileo threw from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, not to mention the legend of Isaac Newton’s apple. By looking at Leonardo’s drawing, Dr. Gharib believes he was able to prove that Leonardo had also conducted similar experiments.

In the drawing, Leonardo notes where the movement of the water-filled jug had started, labeling it with the capital letter A. Then, to show the falling material, he adds a series of vertical lines descending from the top line of the triangle, and the series lengthens as it moves away from the jug. This design would thus “transform the hidden nature of gravity into visible increments,” reads the New York Times. The jug experiment, Gharib said, revealed that gravity was a constant force that resulted in constant acceleration, a constant increase in speed. Leonardo, aware then that the water would not come out of the jug at a constant speed, but accelerated, was able to demonstrate this.

Researchers say Leonardo wrote in the code that he witnessed fast-moving clouds from which hailstones had fallen, which they believe inspired the experiment.

Gharib said that “the fascinating part” of Leonardo’s feat was that it allowed him to estimate a constant of nature, the gravitational constant, represented in physics today by the letter G. The constant quantifies the exact magnitude of the force of gravity and thus how fast an object can accelerate. And according to Gharib, Leonardo was able to calculate the gravitational constant with an estimated margin of error of, at most, 10 percent of the modern value. “It’s astounding,” the scholar said. “This is the beauty of what Leonardo does.” Finally, the researchers explained, Galileo and Newton approached the problem in a more complex way because they had better mathematical tools and more advanced devices to measure time as objects fell. They acknowledge Leonardo as a pioneering scientist, however. And Gharib said many art historians have examined the Arundel Codex, but the same cannot be said for scientists, so Leonardo’s notes are still “an open book that they haven’t looked at yet, haven’t spent time exploring. There is so much more to discover.”

Pictured is folio 143 of the Arundel Codex.

|

| According to an American study, Leonardo experimented with gravity. A century before Galileo |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.