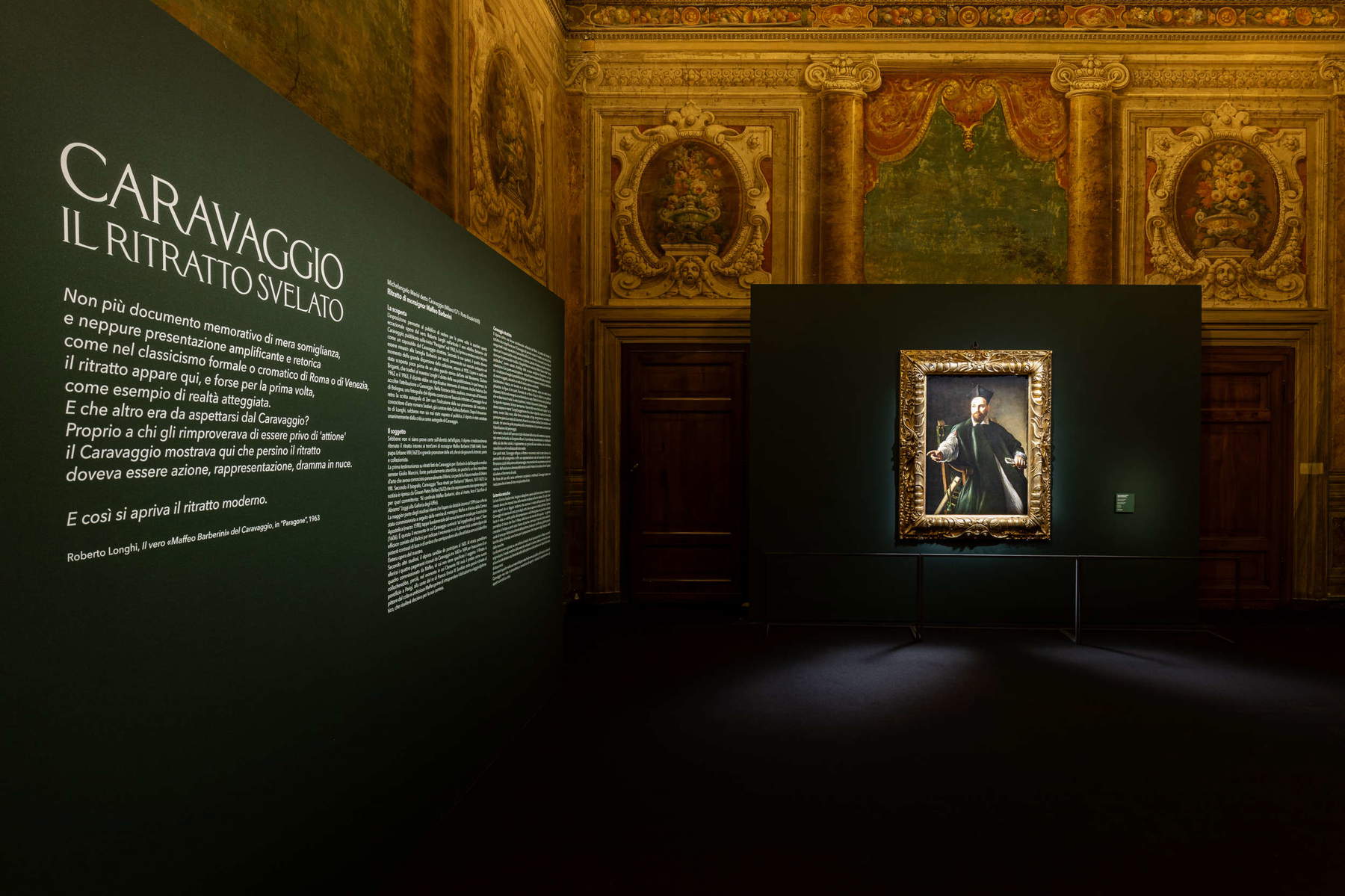

A never-before-seen Caravaggio is unveiled to the public. In fact, from Nov. 23, 2024 to Feb. 23, 2025, the National Galleries of Ancient Art in Rome will host an event of historic significance: the first public exhibition of the Portrait of Monsignor Maffeo Barberini, a work by Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi; Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610), which can be seen in the Landscape Room of Palazzo Barberini.

Never exhibited before, the painting comes from a private collection and is unanimously considered an autograph work by Caravaggio. The work depicts Maffeo Barberini (Florence, 1568 - Rome, 1644), the future Pope Urban VIII, in his early thirties. Depicted seated in an armchair placed diagonally, the monsignor is immersed in a dramatic atmosphere created by strong chiaroscuro, with his face and hands illuminated by a powerful light that pierces the darkness of the background. The character, dressed in talar robes in shades of green, holds a folded letter in his left hand, while his right hand, with a sudden gesture, seems to be heading toward an interlocutor outside the scene. The dynamic movement, the intensity of the gaze and the refined details of the painting reveal Caravaggio’s extraordinary talent in the psychological and narrative rendering of his subjects.

“This is the Caravaggio everyone wanted to see, but it seemed impossible,” says Thomas Clement Salomon, Director of the National Galleries of Ancient Art. “We are happy and proud that the National Galleries of Ancient Art has succeeded in this feat and that for the first time ever this masterpiece can be admired by all at Palazzo Barberini.”

The painting was first attributed to Caravaggio by Roberto Longhi in 1963. “No longer a memorative document of mere resemblance, nor even an amplifying and rhetorical presentation as in the formal or chromatic classicism of Rome or Venice,” the art historian wrote, “the portrait appears here, and perhaps for the first time, as an example of posed reality. And what else was to be expected from Caravaggio? Precisely to those who reproached him for lacking ’actione,’ Caravaggio showed here that even the portrait was to be action, representation, drama in nuce. [...] And thus the modern portrait was opened.” The portrait of Maffeo Barberini fills a significant gap in the portrait production of Merisi, known more for his sacred and mythological subjects. Caravaggio’s portraits, in fact, are extremely rare, and many of them have been lost.

Longhi, who published the work in 1963 in Paragone magazine, considered it a landmark for understanding the evolution of the painter’s portraiture. The discovery of the painting is intertwined with a dispute between Longhi and Giuliano Briganti, who was its first discoverer according to the correspondence between the two, and he too attributed the work to Merisi, first, later ceding to Longhi the right to publish it (confirmation of what happened is in a letter dated July 2, 1963). According to Longhi’s hypothesis, the painting must have remained in the Barberini family for centuries, reaching the antiquarian market at the time of the great dispersion of the collection, around 1935. At that time, between 1962 and 1963, the painting underwent significant restoration. Federico Zeri also accepted the attribution to Caravaggio. In the scholar’s Photo Library, kept at the University of Bologna, a photograph of the painting in the file titled Caravaggio has Zeri’s autograph inscription on the back indicating its provenance from the Roman art dealer and connoisseur Sestieri, former curator of the Barberini Gallery. Since Longhi’s discovery, although it has never been exhibited to the public, the painting has been unanimously accepted by critics as an autograph by Caravaggio.

The painting’s autographic characteristics have been confirmed by experts such as Mia Cinotti, who included it in her 1983 Caravaggio monograph, and by other distinguished scholars such as Federico Zeri, Francesca Cappelletti, Gianni Papi, Maria Cristina Terzaghi, Rossella Vodret, Alessandro Zuccari, and Keith Christiansen.

Although there is no certain evidence about the identity of the effigy, the painting is traditionally believed to be a portrait around the age of 30 of Monsignor Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII (1623) and a great promoter of the arts, who from a young age was a scholar, poet and collector. The first account of portraits done by Caravaggio for the Barberini is by the Sienese biographer and physician Giulio Mancini, a particularly reliable source, both because he was a fine connoisseur of art who had known Merisi personally and because he was the future physician of Urban VIII. According to the biographer, Caravaggio “made portraits for Barbarino” (Mancini, 1617 - 1621). The news is echoed by Giovan Pietro Bellori (1672) who specifically mentions two works he executed for that patron: “To Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, besides the portrait, he made the Sacrifice of Abraham” (now in the Uffizi Gallery),

Most scholars believe that the work can be dated to around 1599 and was commissioned following Monsignor Maffeo’s appointment as a cleric of the Apostolic Camera (March 1598), a milestone in the curial cursus honorum for the cardinalate (1606). This is the moment when Caravaggio began “to ingagliardire gli obscuri,” an effective phrase coined by Bellori to indicate the moment when the painter began to create paintings with the powerful contrasts of light and shadow that correspond to the stylistic signature with which the master’s entire oeuvre is identified. According to other scholars, the painting should be dated to 1603. The Portrait could refer to the four payments received by Caravaggio between 1603 and 1604 for the execution of a painting commissioned by Maffeo, the subject of which is not specified. The Portrait would therefore be placed at the time when Clement VIII sent the prelate as papal nuncio to Paris, to the court of the French king Henry IV. He would therefore have been requested to the painter by the cultured and ambitious Maffeo before embarking on the very delicate diplomatic journey that would prove decisive for his career.

The painting fills a considerable gap in Merisi’s activity. The practice of portraiture was far from insignificant for the Caravaggio of the Roman period. The master, according to sources, executed many portraits mainly of personalities of the Curia and of friends and acquaintances, but these works are almost all lost or destroyed. The activity required fast and confident painting due to the presence of the model.

The biographer Mancini reveals that Merisi made portraits “without similitude,” that is, removed from the obligation of accurate physiognomic likeness, and he was valentissimo. With this pictorial exercise - a field of experimentation in naturalistic painting - he best realized the possibility of painting from life and surpassing in vividness the physical reality of men and objects, captured in a unity of vision, action and feeling. The clergyman wears a biretta and a sleeveless cassock, over a pleated white robe. The three-quarter-length figure, illuminated by a beam of light, is seated in an armchair arranged at an angle and emerges from a dark, empty room. Minimized are the attributes that describe her role: the robe, the armchair, the roll of papers, the folded letter. The impatient gaze, the half-closed mouth, and the action of the hand piercing the space “with its right hand suspended and rotating” (Longhi) suggest that she is addressing someone outside the scene, while the other hand, with its rounded shapes, vigorously clutches a letter. In the very foreground is a scroll of documents, closed by a velvet cord, a non-random attractive fulcrum that serves as a perspective guide to the composition and may be a clue to the character’s identification. If the work’s cultural matrices have been identified by critics in Venetian-Lombard Renaissance portraiture, from Giorgione to Moroni, the patron, who is certainly an intellectual from the highest social sphere, is represented here, thanks to the incidental light, with a naturalistic evidence and immediacy quite unprecedented

The light illuminates the smooth, dazzling epidermis, especially on the forehead where a dense impasto is traced that sets the area of maximum incidence on the right eye. The clear eyes are marked by a slight squint that accentuates the vividness of the expression. Typical of Caravaggio is the technique of constructing the eyes, where to separate the sclera from the iris, the painter leaves in view a thin outline of the preparation and on the iris applies a small, full-bodied brushstroke of white lead that fixes the reflection of light and gives intensity to the gaze. The color palette is limited to a few colors: lead whites and earths for the complexion (without cinnabar), copper greens for the dress and back of the chair, cinnabar for the red outlines, yellowish for the studs on the back, and brown earths for the preparation that shine through the thinner layers of the sleeves.

The hues are played out in a symphony of greens, which the light turns on in highly original reflections and arrangements: the metallic green of the robe, which in the shaded parts fades into shades of olive green, and the golden, ringing green of the velvets of the armchair and the cord with the bows of the scroll of documents. Admiring The Painting in its materiality finally allows the public to enjoy a work by Caravaggio that has never been seen before and will enable experts and scholars to delve deeper into its scientific and critical aspects

|

| A never-seen Caravaggio is revealed for the first time: the Portrait of Maffeo Barberini in Rome |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.