A drawing by Michelangelo hits the market: it is recognized as the first of his career

When, in 2019, art historian Timothy Clifford announced that he had identified the first known work of Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564) the stir was great: then, for some time, the drawing he attributed to a very young Michelangelo, less than 15 years old, receded from the news but continued to be the subject of scholarly attention, which has not ceased to debate around this singular Study of Jupiter. And now, the sheet is finally on the market: the London gallery Dickinson presented it at the Florence Biennale Internazionale dell’Antiquariato as a work by Michelangelo, selling for 2 million euros.

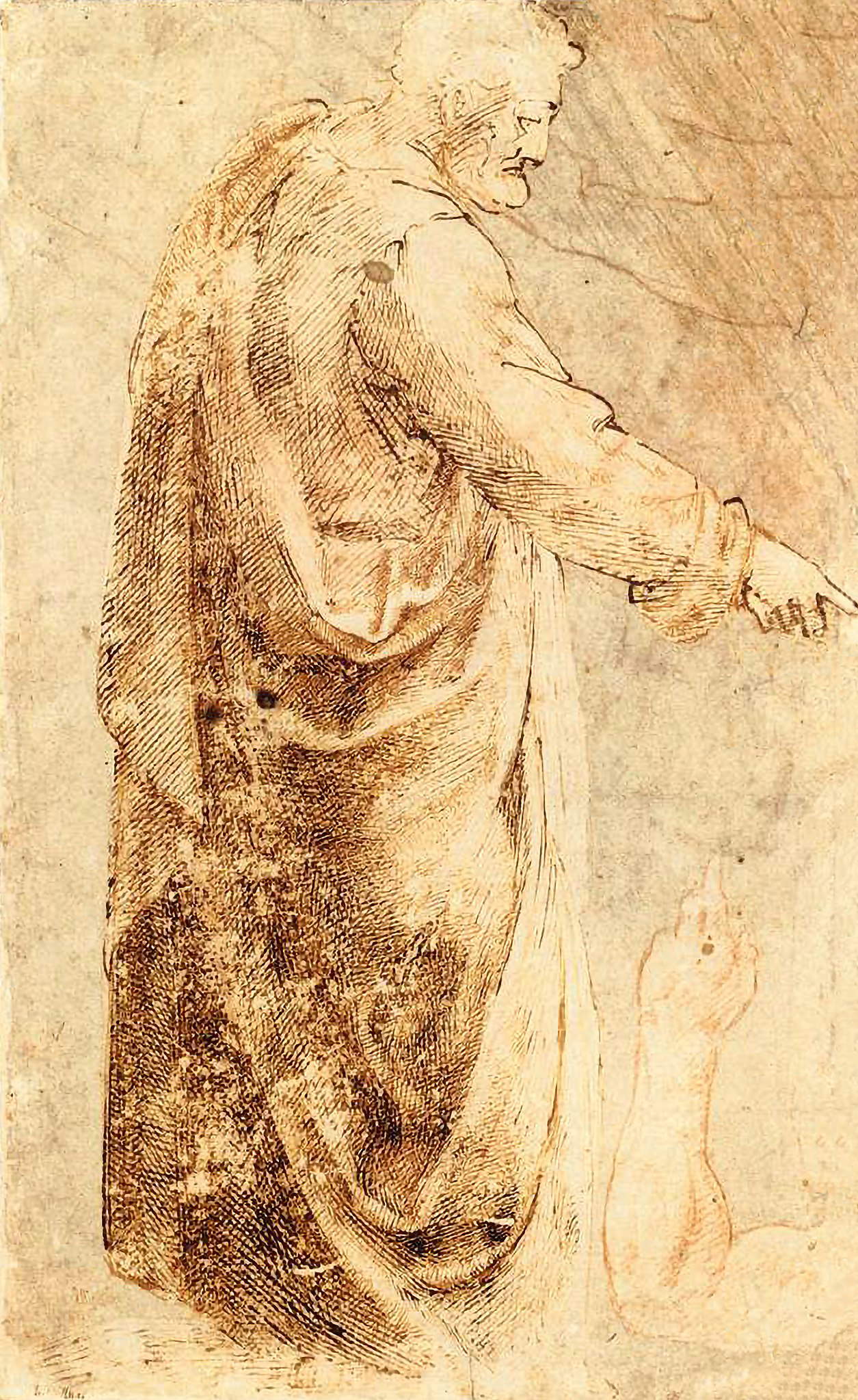

For the gallery, the Jupiter Study “represents one of the most exciting discoveries in the Old Masters sector in recent decades, and is an important addition to the small group of existing drawings by Michelangelo.” The sheet was purchased at auction in Paris in 1989 as the work of an anonymous hand, and is now considered by many scholars to be the Renaissance master’s earliest known drawing. The sketch, in two shades of brown ink, depicts the profile of a bearded man wearing a toga, seated and facing left, caught looking down. He extends his right hand forward and holds a staff or scepter in his left, which rests on his knees; his feet are bare, the right is shown in profile while the left points toward the viewer. The antique throne on which he sits has arms carved with lyre-shaped scrolls and a decorative center section with E-shaped moldings on either side and, in the center, an animal skull. The figure itself is based on a fragment of Roman marble, the lower half of a enthroned Jupiter (1st-2nd century AD) that was then in the collection of collector and merchant Giovanni Ciampolini (d. 1505) in Rome in the late 15th century. This marble, which was later restored with the addition of Jupiter’s upper body and head, is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.

After the discovery, many scholars agreed that the author of the sheet must have been a young man working in Ghirlandaio’s studio in late 15th-century Florence. Exactly like Michelangelo, he passed through the great Florentine painter’s workshop. There, he studied alongside other talented young men, honing his skills and beginning to develop his style. During this period, Michelangelo also benefited from the protection and patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici, who facilitated his access to ancient sculpture and encouraged his ambition. On the basis of comparisons with other early drawings and the significant presence of the two distinctive ink tones, many leading scholars in the field, including Paul Joannides, Timothy Clifford, Zoltán Kárpáti, Miles Chappell, and David Ekserdjian, have argued that this drawing is the earliest known work on paper by the young Michelangelo.

When Ghirlandaio was busy painting the cycle of the Stories of the Virgin in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Michelangelo was introduced to Lorenzo the Magnificent, perhaps through his friendship with Francesco Granacci. This meeting proved invaluable to Michelangelo: the Magnifico, as is well known, allowed him to make drawings of works from his collection of ancient sculpture at his residence near the convent of San Marco. Michelangelo, in the Magnifico’s residence, met several important personalities: the sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni, who had been Donatello’s collaborator and had taken care of the Magnifico’s collection; Angelo Poliziano, the guardian of Lorenzo’s children, a humanist, poet and collector of antiquities; and Giovanni Ciampolini himself, one of the earliest collectors of Roman antiquities.

The survival of other contemporary drawings depicting Jupiter enthroned is evidence of the great fascination with ancient sculpture widespread at the time, as well as of the high regard that, at those chronological heights, Florentine artists had for this fragment. Michelangelo’s drawing is not a simple copy of the enthroned Jupiter, but rather has some relevant differences. As David Ekserdjian has noted, the position of the right foot, which is raised upward from the heel in the marble, rests on the pedestal in Michelangelo’s sheet. In addition, the folds of drapery between the figure’s legs are squarer than they appear in the marble. The upper half of the drawing is evidently an invention, which may explain the detailed description of the lower half of the body, which shows a more cursory study of the face and right hand.

In his discussion of the Study of Jupiter, David Ekserdjian suggested that Michelangelo was not copying directly from the marble, but rather from another drawing depicting the sculpture. This would be in keeping with the practice of the 15th-century Florentine workshop, where apprentices copied their master’s drawings to improve their art. As Clifford pointed out, the ultimate source of the drawing, the marble fragment of Jupiter Enthroned, was in Rome at the time, and Ghirlandaio is known to have regularly traveled to Rome to study recently excavated marble. In the 1568 edition of his Lives, Giorgio Vasari himself explains how Michelangelo had learned from studying Ghirlandaio’s drawings: in particular, Granacci provided the young Buonarroti with drawings by Ghirlandaio every day. It is believed that it was Granacci who first introduced Michelangelo to Ghirlandaio’s workshop and spurred him to ask the master to take him on as his apprentice.

The young Buonarroti began his career in the workshop of his brothers Domenico and David Ghirlandaio at the age of about 12, carrying out commissions for the master and apprentices. In 1488 he was then enlisted as an apprentice for a period of three years, although he remained there for only two. Vasari published, in the second edition of the Lives, the apprenticeship contract drawn up between Domenico Ghirlandaio and Michelangelo’s father Ludovico, signed on April 1, 1488 with the stated intent of instructing Michelangelo in the art of painting. It was through Ghirlandaio’s instruction that Michelangelo came to appreciate, copy and study the work of masters such as Giotto and Masaccio. And it is this proximity to Ghirlandaio that explains the presence of certain details in the Florentine painter’s style in this drawing, such as the drop shapes of the folds. As Zoltán Kárpáti mentioned in the catalog of the recent Michelangelo exhibition in Budapest (2019), where the sheet was first exhibited, Michelangelo was a talented copyist who was able to imitate Ghirlandaio’s technique from his early days as an apprentice.

When the current owner acquired the drawing more than three decades ago, nothing was known about its history, and it was totally unknown to scholars. Early research confirmed that the work originated in Domenico Ghirlandaio’s workshop. The presence of the drop shapes of the folds led Nicholas Turner, formerly with the British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings and an expert on Italian Renaissance drawings, to suggest an attribution to Domenico Ghirlandaio himself. This attribution was rejected by Chris Fischer, who also rejected Everett Fahy’s attribution of the drawing to Fra’ Bartolomeo, an artist who, like Michelangelo, spent time working in Ghirlandaio’s studio. Other scholars such as Francis Ames-Lewis, Jean Cadogan, and Michael Hirst were convinced that the drawing was made by an artist working in Ghirlandaio’s studio.

The drawing’s connection to Michelangelo’s early work was first made by Miles Chappell, an expert on 15th- and 16th-century Florentine drawings. After extensive research, the drawing was first published as a work by the young Michelangelo in 2019 in the catalog accompanying the exhibition Triumph of the Body: Michelangelo and Sixteenth-Century Italian draughtsmanship, held from April 6 to June 30, 2019 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. This research was supported by Paul Joannides, who catalogued Michelangelo’s drawings at the Louvre, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and published Michelangelo’s drawings in the Royal Collection for an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Joannides, in a private communication in October 2015, noted the surprising fluidity with which the quotation from antiquity blends with theartist’s upper body andinvention, characteristic of the way Michelangelo worked and developed during this period. Later, David Ekserdijan agreed with these findings.

The attribution to Michelangelo is based on several factors: chiefly determining it is the fact that the subject, materials, and style of the drawing all agree with what we know of the early stages of Michelangelo’s career. The drawing has two shades of brown ink: this was a technique Michelangelo often used, but in contrast we never see it in Ghirlandaio’s own drawings. Why Michelangelo had chosen this technique is not known: perhaps, he was simply experimenting with means to achieve a wider range of tones in his drawings. However, this was not a technique he used to revise or modify his drawings, as he used the two tones from the very beginning of drafting, rather than using the darker ink to correct passages originally drawn with the lighter one.

Joannides, Clifford and Ekserdijan have speculated that Michelangelo’s Study of Jupiter is his earliest extant work on paper, dating from about 1490. Prior to the discovery of the present drawing, the earliest known work accepted by scholars is a Study of Two Figures by Giotto now in the Louvre, dating from about 1490-1492. Of all Michelangelo’s known drawings, the one in the Louvre is the closest, stylistically, to Ghirlandaio himself, when the lessons of his apprenticeship were most clearly felt and expressed. Clifford describes the “mellifluous ebb and flow of the draperies” from Ghirlandaio’s hand: “They are caught and cast in curls, pools and depressions, with the latter often taking on a ’tear’ form.” Clifford also compares the gathered drapery around the stomach of the figure leaning forward in the Louvre drawing to the folds clustered and gathered in Jupiter’s robe in the Dickinson sheet, described using a network of hatching. Slightly later still, dated roughly to 1492-93, is the Male Figure from Masaccio now in Munich. Considering the progression from the Dickinson sheet, through the Louvre example and on to the Munich drawing, it is possible to see how Michelangelo’s hatching technique is becoming more confident in a short period of time. The description of the figure’s head, its profile described in vivid outlines, with the pen evidently pressing firmly in some places and lightly in others, is very similar to that in the Study of Jupiter. Also similar are the ink brushstroke under the nose (bolder), the V-shape of the eye socket in profile, and the rounded, slightly bulbous chin. A wavy line describes the contours of the sleeves while hatching runs parallel to the arm and also crosswise to add depth and dimension.

Further comparisons can be made with a drawing of Three Standing Men preserved in the Albertina in Vienna, depicting three figures probably copied from a scene in Masaccio’s destroyed fresco in the cloister of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. It is dated around 1492-1496, a period when Michelangelo was moving further away from Ghirlandaio and the hatching used to describe the folds of the cloaks was becoming denser and more complex, with multiple layers of parallel strokes running at an angle to each other. These figures are again shown in profile, and although the anatomy is more assured, some distinctive stylistic features remain: the V-shaped eye sockets, for example, or, as Clifford notes in relation to the Louvre and Munich drawings, the slightly rounded chins. Scholars have also noted some weaknesses in the drawing, typical of a young artist working on his art, seen, for example, in the flat and only vaguely sketched foot of the figure on the back. The hands, notoriously difficult body parts for an artist to master, are absent. The drawing from this period that has come to light most recently is another copy from a fresco by Masaccio: this time, a copy from the Baptism of the neophytes in the Brancacci Chapel, which sold for 23 million euros at Christie’s in 2022. This drawing was reworked by Michelangelo at a later date using brush and ink, but the network of hatching forming the robes of the figures accompanying the central nude can be compared to that seen in the Dickinson drawing.

When the drawing was discovered in 1989, it underwent conservation work by André Le Plat, previously in charge of conservation at the Louvre’s Cabinet du dessin. Le Plat observed that the drawing had been cut from a larger sheet, which probably included other studies, and that the irregular right edge showed traces of tears that suggested there had been some moisture problems in the drawing’s history. In his view, the drawing originally must have been stronger and denser to the touch, and this is evident in a comparison with some of Michelangelo’s other studies from the 1590s, in which the density of the cross-hatching is more pronounced. However, as Clifford noted, there are close parallels between the slightly looser method of cross-hatching in the Study of Jupiter and the hatching used in the sloping figure in the Louvre drawing, particularly on the right arm and in the curve where the arm meets the back.

A particularly interesting feature of the Study of Jupiter is the unconvincing and awkward depiction of the left hand. This hand was an invention of the artist and, unlike the lower half of the drawing, was not copied from an earlier model. It is known that Michelangelo was more concerned with the monumentality of his figures than with the details of the extremities, as noted by Jean Cadogan, who observed that “Michelangelo was not interested in the detailed drawing of hands and heads when copying from the Old and Renaissance masters. His main interest was in rendering volume, mass, and monumentality in his subjects. I think this is evident when you look at all his copies from the Renaissance masters.”

Only later did Michelangelo become interested (indeed, it became almost an obsession) in the study of anatomy, and in these early drawings there is a constant weakness in the hands and feet, typical of an artist without significant experience. In the Louvre drawing of comparable date, the stooping figure is shown with a hesitant, flaccid hand, with a heavier, darker outline that suggests an attempt to rework and refine it, though with little success. An awkwardness also detectable in the Munich drawing.

The Study of Jupiter has already aroused a great deal of curiosity, given also the numbers that Michelangelo’s drawings are capable of achieving, by virtue of their extreme rarity: toward the end of his life, in fact, Michelangelo burned, or ordered to be burned, most of his drawings (about 600 survive, most of them preserved in museums). Consequently, when a sheet arrives on the market, it is always the object of much attention. In this case, however, compared to some sheets that have gone to auction recently, the demand is lower. But we are still talking about a 2 million euro work and a sheet that has all the credentials to shake up the market.

|

| A drawing by Michelangelo hits the market: it is recognized as the first of his career |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.