Throughout his career, Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890) painted hundreds of works of art, now preserved in museums around the world: it is estimated that Van Gogh authored about nine hundred paintings and over a thousand drawings. Contrary to what one might think despite the vast amount of Van Gogh’s works that we know of, his career was very short-lived: the artist, in fact, came to painting very late (first he worked as a salesman at the Goupil art house and then, from 1876 to 1880, he spent a period as a teacher in England, after which, back home, he worked as a bookseller in Dordrecht: only from 1881 did he devote himself fully to art, albeit without success), and his parabola lasted less than ten years, from 1881 until his death in 1890.

Full recognition also came only posthumously. Although Van Gogh was an extremely well-read artist, contrary to what mainstream narratives might suggest (his work at the Goupil art house enabled him to study art in depth, plus he possessed a good personal library), and although he could boast the friendship of some of the best artists of the time (his connection with Gauguin is well known), the innovative scope of his art was not immediately perceived by his contemporaries. Van Gogh was, however, among the first artists, along with Gauguin himself and a few others, to radically change the course of art, which also thanks to him began to focus on the motions of the artist’s soul and interiority, rather than on nature or the external aspects of reality.

Today we know Van Gogh’s art to perfection also because we preserve almost in its entirety his epistolary corpus: in particular, the letters sent to his brother, the art dealer Théo van Gogh (Zunder, 1857 - Utrecht, 1891), in which the artist, confiding intimately, revealed his dreams, ambitions, quests, and even his difficulties and torments, are a most valuable source for understanding the motivations that animated his art. However, having to trace a path in his art, which works best help to understand his painting? The choice is very difficult: however, we have made an attempt and try below to list fifteen fundamental works to begin to become familiar with Vincent van Gogh’s art, chosen so as to cover his entire career, although in a balanced way, that is, with greater concentration in the periods when his painting reached its most innovative outcomes.

This is the artist’s first known work, marked with inventory number F1 in the general catalog of Van Gogh’s works. The painting, which is unsigned, is also mentioned in a letter sent to Théo on December 12, 1881. The painting attests to the beginnings of the painter, whose early works were devoted to realist imitation art, depicting (and this would be a constant throughout his life) what was available to him, in this case some objects he had at home. It is in this case little more than an exercise in form and color, which the artist nonetheless resolves in spite of little experience, managing to convey the differences in texture of the painted materials. We are, however, still a long way from the mature outcomes of his art.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Still Life with Cabbage and Clogs (November-December 1881; oil on canvas, 34.5 x 55 cm; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) |

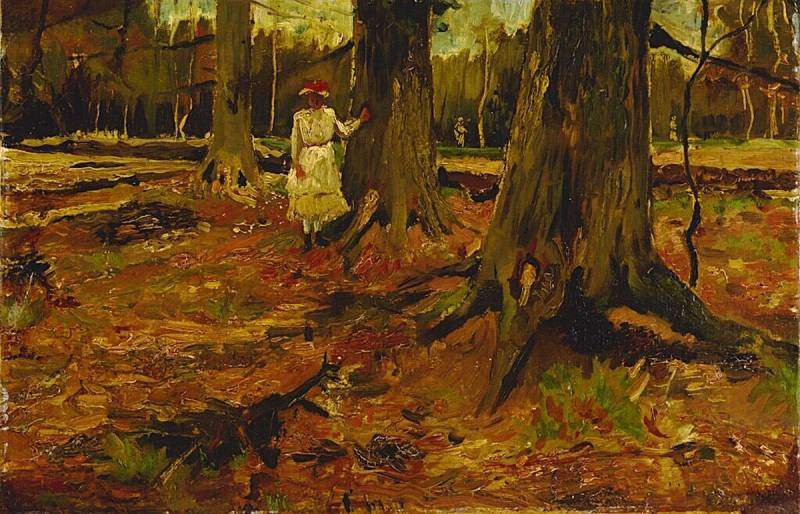

The Kröller-Müller Museum houses the world’s second-largest collection of Van Gogh’s works (the first being that of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam), and to this collection belongs Girl in a Wood, another unsigned work, which depicts a girl inside a forest near The Hague: this is where Van Gogh went to carry out his first experiments en plein air, beginning to mature that close relationship with nature that would be another of the founding elements of his art (we also devoted a lengthy in-depth article in the magazine to this theme). The theme of autumn, with its colors transforming the appearance of the forest, gives Vincent a way to begin to express his sentimental vision of nature.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Girl in a Wood (1882; oil on canvas, 37 x 58.8 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

The work is known in two versions, both dating from the same period and preserved, one at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and the other at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo. It dates from the period the artist spent among miners in the Borinage, a rural area of Belgium that at the time lived almost exclusively on agriculture. Van Gogh, having come into contact with the harsh reality of the peasants who lived only off the fruit of their lands, drew from this experience a remarkable impact: he lost all hope in religion (before becoming a painter he had expressed the desire to be a Protestant pastor, the same job his father did: the experience in the Borinage, however, made him radically change his mind), and he matured new political and social convictions. “A peasant,” he would write in a letter to Théo, “is truer in his moleskin clothes among the fields than when he goes to mass on Sundays in a kind of society dress. In the same way I think it is wrong to give a painting of peasants a kind of smooth, conventional surface. If a painting of peasants smells like bacon, smoke, vapors rising from boiled potatoes [...], it’s all right, it’s all right for that to be the smell of stables.”

|

| Vincent van Gogh, The Potato Eaters (April-May 1885; oil on canvas, 82 x 114 cm; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) |

This is a very little-known painting, but it is nonetheless interesting because it is one of the works that closes the Nuenen period (the town where the artist stayed between 1883 and 1885, spending long periods in contact with the miners of the Borinage), and where the artist began to really bring his talent to bear. And then the work is not insignificant because it is one of the first instances in which Van Gogh operates that transfiguration of reality according to his own feeling that will be one of the cornerstones of his painting in the end of his career. The piece depicted in this Spanish painting has not been identified with certainty given the absence of reference points. Again, the twilight atmosphere allows the artist to grapple again with those somber tones that he had admired in the Dutch paintings of the seventeenth century and that characterized the early part of his career. As is well known, in his later years his palette would instead embrace a luminosity unknown in the paintings of his early years.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Sunset Landscape (1885; oil on canvas, 35 x 43 cm; Madrid, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza) |

This is the first work directly dependent onJapanese art, which Van Gogh delved into during his stay in Antwerp (1886), when he managed to procure several Japanese prints traded cheaply by merchants in the harbor area. From his contact with Japanese art, Van Gogh gained a simplification and compositional freedom that would later accompany him for the rest of his career(at this link you will find an article to learn more about Van Gogh’s relationship with Japan). This oil on canvas is a free interpretation of a work by Kesai Esan that in turn had been reproduced in the magazine Paris illustré (issue of May 4, 1886).

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Japan: Oiran (October-November 1887; oil on canvas, 100.7 x 60.7 cm; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) |

The protagonist of this painting dating from the Paris period is a fritillary plant (a bulbous plant that blooms in spring) inside a copper pot. It is a painting that is affected by the contact of the friendship that Van Gogh developed with Paul Signac and that imprinted a further turn to his art: Vincent, drawing on the theories of pointillisme borrowed from Signac, realized the blue background by means of many close dots that reflect each other, and he does the same with the copper vase, achieving a result of luminosity that is unprecedented in his art. Moreover, here Vincent, who had studied sixteenth-century painting, also employs complementary colors (in this case, the blue of the background and the orange of the flowers) to have a greater brilliance. Van Gogh often painted flowers because they gave him the opportunity to do many experiments with colors.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Imperial Fritillary in a Copper Vase (1887; oil on canvas, 73.5 x 60.5 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

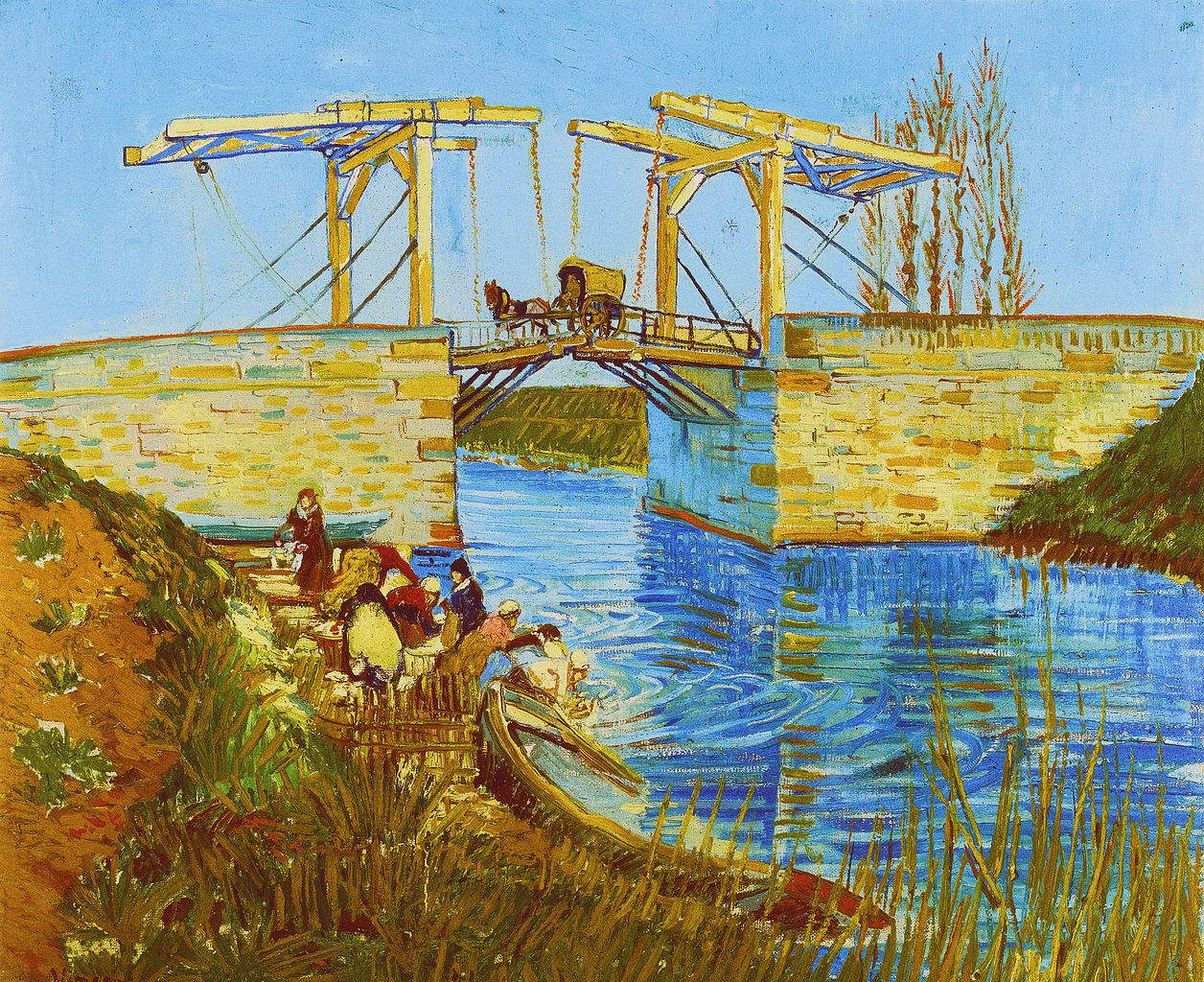

The Langlois Bridge is one of the best known works from the Arles period (where the artist moved in February 1888 with the intention of brightening his palette in the light of the “Midi”) and is deeply indebted to the Japanese prints Vincent had continued to buy and collect. Provence, for Van Gogh, was a kind of “European Japan,” and given these ideal assumptions it is easy to understand why The Bridge of Langlois also makes use of the bold views and the kind of flat two-dimensionality that are two typical elements of ukiyo-e, the woodcuts of Japanese artists. “The country,” Vincent would write to Théo from Provence, “seems to me as beautiful as Japan because of the clarity of the atmosphere and the effects of joyful color.” Beginning with this painting, and others from the same period, Van Gogh came to use very bright colors set in light tones.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, The Langlois Bridge (March 1888; oil on canvas, 59 x 74 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

It is impossible to draw a list of Van Gogh’s works without referring to his portraiture, and the portrait of letter carrier Joseph Roulin is one of the most significant examples of this. Van Gogh wanted to portray him because of his imposing presence (his beard, the artist said, reminded him of that of the Greek philosopher Socrates), as well as because of their friendship: there are several portraits of Roulin, although the one in Boston is the most famous. According to Giulio Carlo Argan, Roulin’s portrait is one of the works from which Van Gogh’s vision of art, and in particular of the artist’s role in the face of reality, is best evinced: “He makes a portrait of a letter carrier, Mr. Roulin. [...] There is no social interest: he does not portray Mr. Roulin because he is, nor although he is, a letter carrier, nor because he interests him as a human type. [...] It is a reality that he neither judges nor comments on: he can only passively undergo it or make it his own, re-make it with the material and acts that are of his own craft as a painter, of his own existence. In fact, he builds it, models it with color: he experiences the thickness of cloth in the opaque density of turquoise, [...] the transparency of flesh in the cold veils on pink.”

|

| Vincent van Gogh, The Postman Joseph Roulin (August 1888; oil on canvas, 81.3 x 65.4 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

Vincent’s Room at Arles has become one of the symbols of Van Gogh’s art, partly because of its simplicity, partly because the transfiguration of reality (see, for example, the wall with the crooked pictures, the unrealistic colors of the background window, the bold perspective foreshortening) is typical of the last phase of Van Gogh’s art, although he would later reach further advanced levels. In addition, the painting depicting his room (there are several, however: at least three are known) has also become iconic because it allows us to enter Van Gogh’s intimacy, to see how he lived (on the edge of misery), what objects kept him company in his daily life. A work that, in short, tells us about the artist: that is also why it is so famous.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Vincent’s Room at Arles (October 1888; oil on canvas, 72 x 90 cm; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) |

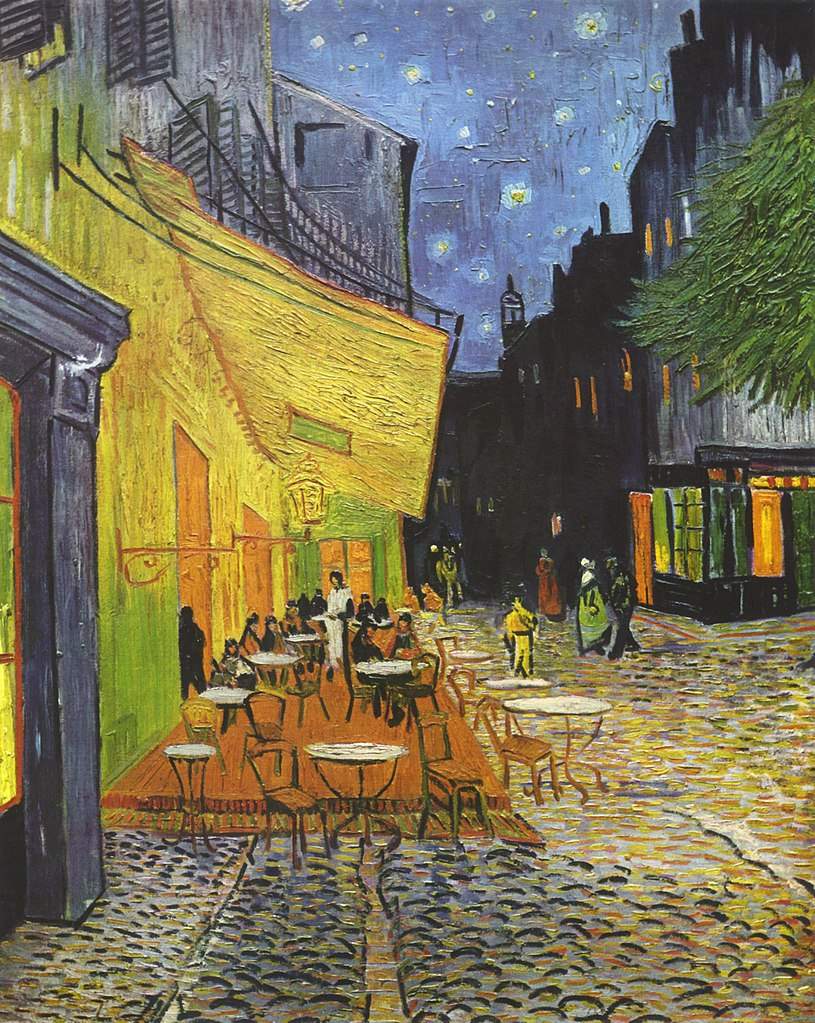

Another iconic painting, known because it allows us to enter the Arles of 1888, but also important for a reason actually little known to the general public, namely that it is a painting of literary inspiration: in fact, Vincent made the Terrace after reading the very famous novel Bel-Ami by Guy de Maupassant. Why this is so is explained in a letter to Théo: "the beginning of Bel Ami contains a description of a starlit night in Paris with the cafes brightly lit on the boulevard and is roughly the same subject that I have just painted. It is also an unusual painting because it is one of the few works of his later years where the lines become more relaxed and where the impasto is more worked than in other coeval works, a sign that the artist had to paint the work in complete serenity, as opposed to what he would do in the period immediately following. However, there is no lack of certain elements, such as the excavations in the impasto and the thick brushstrokes, which the artist nonetheless continued to use, giving relief to the painting.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Café Terrace in the Evening, Place du Forum, Arles (September 16, 1888; oil on canvas, 80.7 x 65.3 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

Van Gogh painted sunflowers during both his stay in Paris and his stay in Arles: in Paris the sunflowers were cut, while in Arles the painter always placed them in a vase. The Paris sunflowers are known in four versions, while the Arles sunflowers are known in seven versions (one of which, the one formerly preserved in Japan, was destroyed during World War II in a U.S. air raid). They are among Van Gogh’s most famous works so much so that they have become further icons of his art: the sunflower was for Van Gogh a kind of symbol of the light of the south and it is for this reason that it is part of his art. In addition, sunflower is chosen for its color (Van Gogh loved yellow, and this flower therefore gave him the opportunity to experiment with its various hues): as was always the case in his floral still lifes, flowers become a kind of “pretext” for researching color.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, The Sunflowers (1888; oil on canvas, 91 x 72 cm; Munich, Neue Pinakothek) |

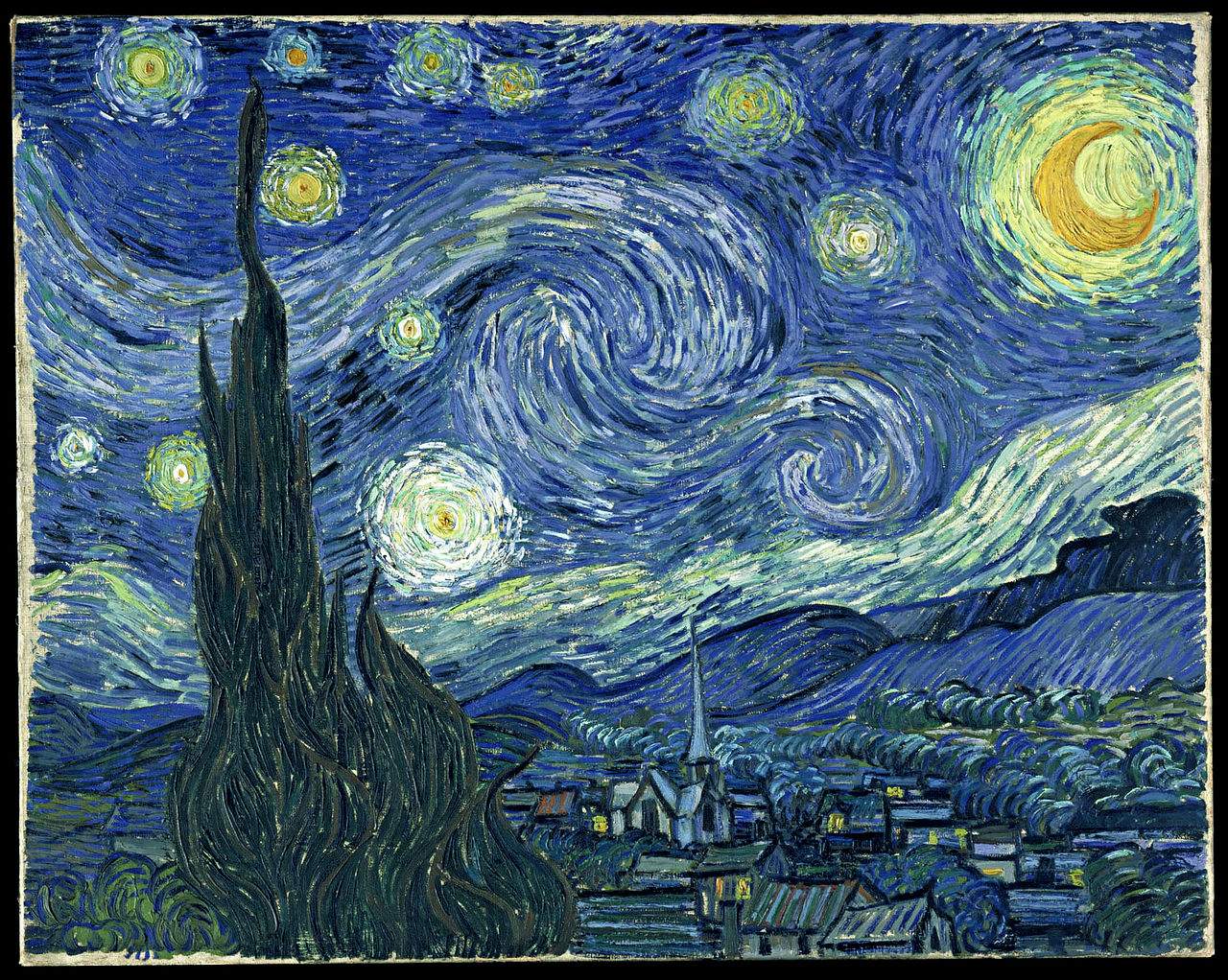

This is one of the earliest works from the period the artist spent in the Saint-Rémy-de-Provence psychiatric hospital to be treated for his mental illness, the most difficult and tormented of his career, but also a time when his art reached new heights. It is the celebrated night view of the village of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, which is painted by the artist--as he sees it within himself. It is an evocative work, representing not a real view (there are very few contacts that the landscape has with reality), but an inner image.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night (June 1889; oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art) |

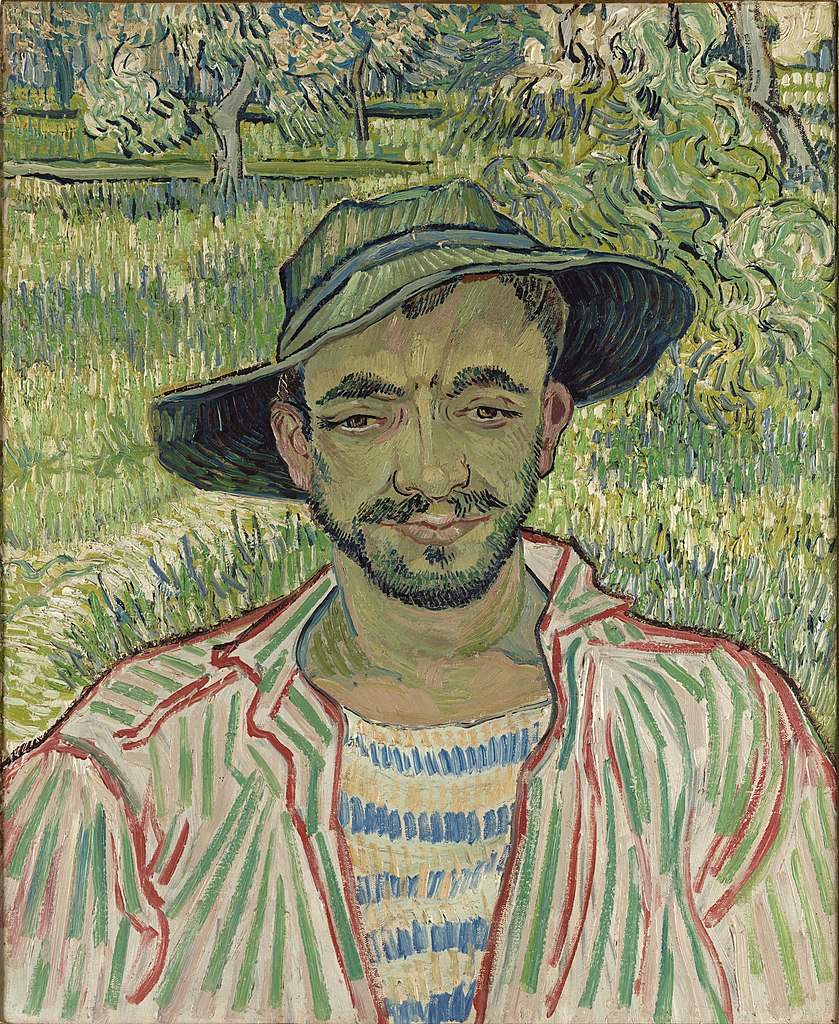

The portrait of this Provençal peasant is one of the rare works by Van Gogh preserved in an Italian public collection, probably the most important of all. Some elements of the last Van Gogh return: the use of primary and complementary colors, the very dense impasto, the partly threadlike and partly sinuous brushstrokes, and the juxtaposition of short brush strokes according to a technique borrowed from the pointillists. It is considered one of the masterpieces of Van Gogh’s portraiture and is one of 140 paintings the artist made while he was hospitalized in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, The Gardener (September 1889; oil on canvas, 61 x 51 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

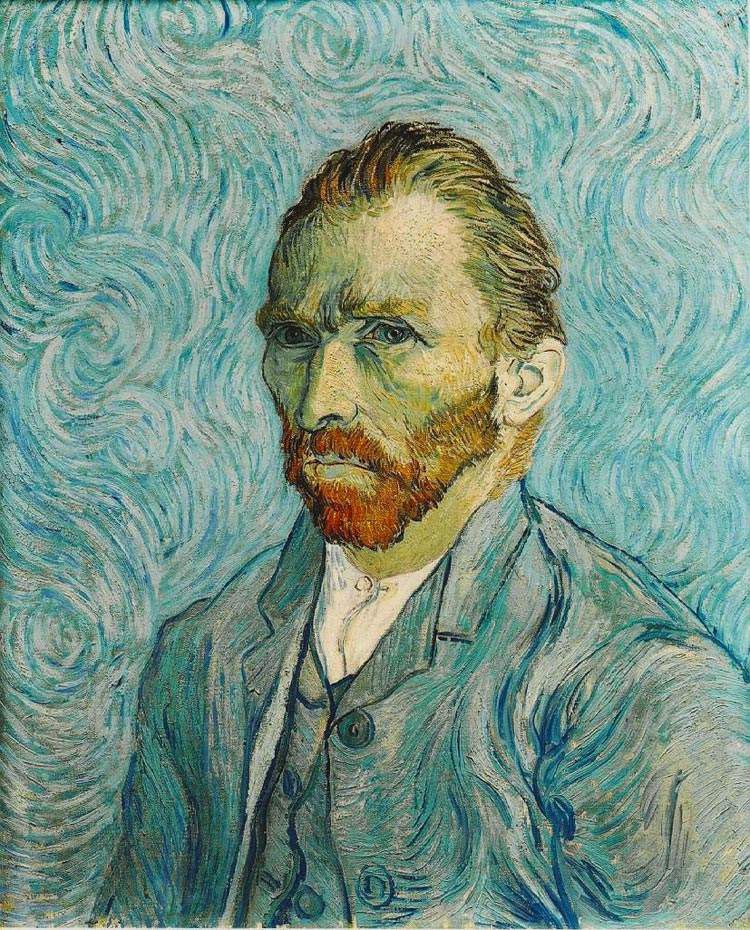

Van Gogh produced a large body of self-portraits, and the one painted in 1889 in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence is probably the most famous of his career. When he painted it, the artist believed that he had recovered from the illness that had made him insane: “You will notice,” he wrote in a letter to his brother Théo, “how the expression of my face is calmer, although it seems to me that the gaze is more unstable than before.” Perhaps it is precisely the alienated gaze (along with the wavy, undulating background) that have made this masterpiece so famous, manifesting the symptoms of a state of neurosis that is still probably unresolved.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, The Gardener (September 1889; oil on canvas, 61 x 51 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

Wheatfield with Flight of Crows has long been thought to be Van Gogh’s last work: it is not, although it appears to belong to the extreme stages of his activity. Certainly, it is one of the artist’s most painful paintings: the tense and nervous brushstrokes with which the artist paints nature (the wheat, the sky, the crows), the extremely bright colors, and the disorder that cloaks the composition are indicative of the inner heartbreak the artist felt just days before his death. It is the artist himself who communicates these feelings of sadness, of a bad mood, as if he felt threatened by an unknown evil.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Flight of Crows (1890; oil on canvas, 50.3 x 103 cm; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) |

|

| Works of Van Gogh: 15 masterpieces to learn about the great artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.