Vorticism. History and style of the English davantgarde movement.

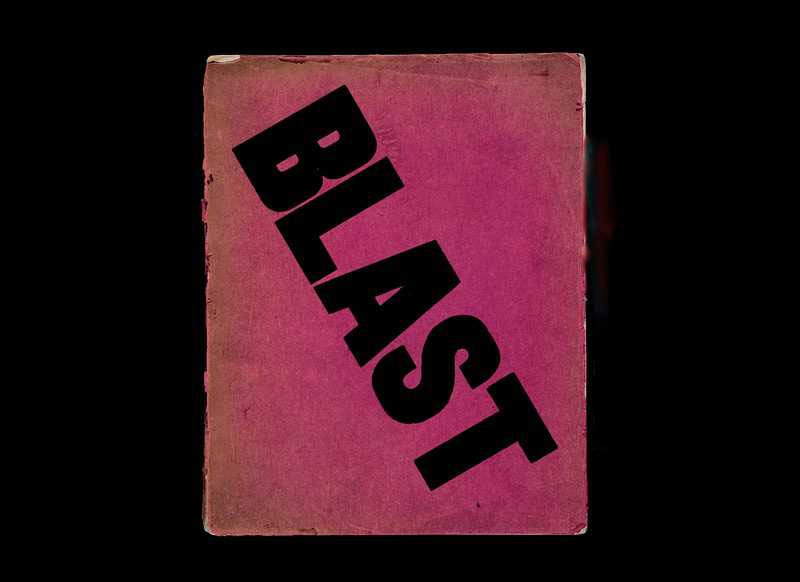

Vorticism was a short-lived literary and artistic movement that flourished in England in 1914 by British painter and writer Percy Wyndham Lewis (Amherst, 1882 - London, 1957) and a diverse group of young artists. The name of the movement was coined by the poet Ezra Pound (Hailey, 1885 - Venice, 1972) who was a passionate supporter of it and participated in it through the magazine “Blast,” through which the Vorticists manifested themselves on the London art scene and constituted an effective stimulus to English artistic renewal.

The artists involved along with Lewis and Pound, were poet Lawrence Atkinson, painters William Patrick Roberts, Cuthbert Hamilton, Fredrick Etchells and Edward Wadsworth and painters Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismor, sculptors Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and others whose researches presented similar characters to those expressed in their manifesto.

Using the tools of contradiction, humor, and rhetoric, the Vorticists celebrated the energy and dynamism of the modern machine age and declared an assault on British artistic traditions, becoming England’s first radical avant-garde group to relate art to industrialization. While drawing many cues from Cubism and especially Futurism, they deliberately distanced themselves from them in their search for a "pure form" centered in their historical present.

Vorticism expressed itself through prose and poetry and promoted a geometric graphic and pictorial style tending toward the abstract, with hard lines and sharp angles in bold, contrasting colors that tended to emphasize the dynamism of industrialized cities, opposing the soft, curved lines of 19th-century sentimentalism. In addition to painting, the Vorticist aesthetic affected various other media, from typography and design to sculpture, in an attempt to transform the way people interacted with those new urban and economic living conditions. The horrors of World War I, however, dampened the group’s energy.

History of Vorticism

The programmatic text of the English art movement was published by Percy Wyndham Lewis with the help of Ezra Pound in the first issue of the magazine they founded, Blast, in June 1914. In a sequence of twenty pages, characterized by a dynamic graphic layout and underlined and bold fonts of various sizes, the Manifesto listed under the two labels "blast“ and ”bless" everything that Vorticism contested and supported.

Lewis’s writing was in polemic with Futurism, the first historical Italian avant-garde of the twentieth century, and with its founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, with whom he had come into contact and then disagreement after their meeting in London in 1910. Against the legacy of the past and against the illusions of the future, and for that very reason against Futurism, Vorticism extolled the vital dimension of the present and the vigorous sensation of being “traversed” by the raw vital energy of the world. Writers and artists were committed to representing the vitality of the modern era with what their leader described as “a new living abstraction.” The cover proclaimed this bold goal by affixing the words"blast“ diagonally across a bright pink page. Ezra Pound described it as a ”large pamphlet covered in magenta." Inside it featured a number of bold typographical innovations to engage the reader, and text and illustrations by Pound, Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Edward Wadsworth and others, alongside an excerpt from Ford Madox Ford ’s novel The Saddest Story, better known by its later title The Good Soldier.

When Pound used the image of the vortex to describe the creative energy emanating from this group of artists, they elected it as a metaphor for much of their aesthetic theory. “Long live the vortex!” wrote Lewis, “Blast aims to be an avenue for all those vivid and violent ideas that could reach the public in no other way....”

By producing a magazine, a cheaply distributed periodical, these artists were offering an alternative to official art displayed in museums and literature printed by established publishers. The intention was for it to be an assault, visual and conceptual, on the British cultural establishment, rejecting inclinations for class snobbery, do-goodism, standardization and romantic inclinations, to embraceinnovation,radical art,individualism, machinery andurbanization, in an attempt to release the vitality of the modern world. Only two issues were published, but they were essential to understanding the aims and attitude of the Vorticists, containing some of the most significant poems and visual artworks of that experience.

After the first issue in 1914 that featured the group’s manifesto, published only a few weeks before the outbreak of World War I, the second issue came out a year later, in July 1915: decidedly more sober even from the monochrome cover, with a woodcut by Lewis, it signaled the effects of the war on the positions set by the Vorticists just before. This issue offered more poetry and prose, with contributions by Ezra Pound, Helen Saunders, and Jessie Dismorr, including two poems, Preludes and Rhapsody on a Windy Night later to become famous, by the American T.S. Eliot, who had become associated with the movement through his friendship with Pound.

Among the singular aspects of the second and final Blast of 1915 is that it also contained Vortex: Written from the Trenches by sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, a text written from the trenches, published posthumously and with which the artist’s death was announced, having been killed in the war shortly before the magazine was published. Also in 1915, during the war, the group held its first exhibition at the Doré Gallery in London, which included works by key members of the group, including Lewis, Saunders, Dismorr, Fredrick Etchells and Gaudier-Brzeska himself, as well as a number of other non-Vorticist artists who were nevertheless invited to show their work. Unfortunately, however, Gaudier-Brzeska’s death shortly before overshadowed their importance. Later, Lewis and other members also went to the front.

In 1917 Pound and American collector John Quinn organized the only contemporary Vorticist exhibition outside England, at the Penguin Club in New York City. Conditions at that time of war made it difficult to transport the works to the United States, and the exhibition did not generate much public or press involvement. In 1920 Lewis then tried to revive the movement with "Group X," a London exhibition at Heal’s Gallery in which he again brought together some of the Vorticist artists, who were meanwhile taking their art in new directions. The original group, however, never reunited; the prewar momentum had been lost.

Themes and style of the major exponents

The Vorticist group emphasized both the literary content and the visual aspects of their manifesto at the same time. The rhetoric used in the writings secured the movement a place in art history alongside Futurism and Dadaism. Wyndham Lewis himself was, first and foremost, a writer, flanking two of the most famous poets of the Modernist period Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. In addition, other members of the movement who were primarily visual artists, such as Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jessica Dismorr, were encouraged to publish their literary texts in Blast, along with their own images. The decision to disseminate their art and ideas in the form of a magazine was very significant, first because of the format, which allowed the members’ disparate creative impulses between literature, visual arts, and design to be combined, and also in that it allowed more people, who could not otherwise afford to collect artwork or expensive books of poetry, to purchase it by supporting a real artistic product. Although it did not reach a very large audience at the time, to this day Blast 1 and Blast 2 remain the group’s most important legacy. Original copies are held in British collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, Tate, Chelsea College, University of Exeter Special Collections, and American collections, Yale University, Wake Forest University, University of Delaware, and others.

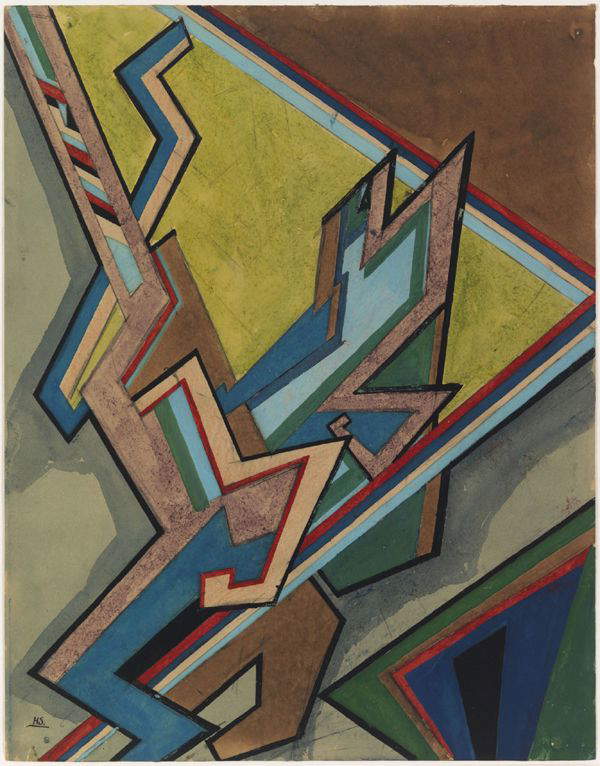

Vorticism established its most important idea in the vortex image, developed in two and three dimensions on paper and canvas and in sculpture. These artists were deeply interested in the swirling quality of life at that time, and their attention turned to the search for a still point, a still center in the impetuosity of motion, which symbolized artistic creation. “You immediately think of a vortex,” Lewis stated, “at the heart of the vortex is a great silent place where all the energy is concentrated; and there, at the point of concentration, is the vortexist.” The compositions were based mainly on intersections of diagonals firmly contained in the picture plane.

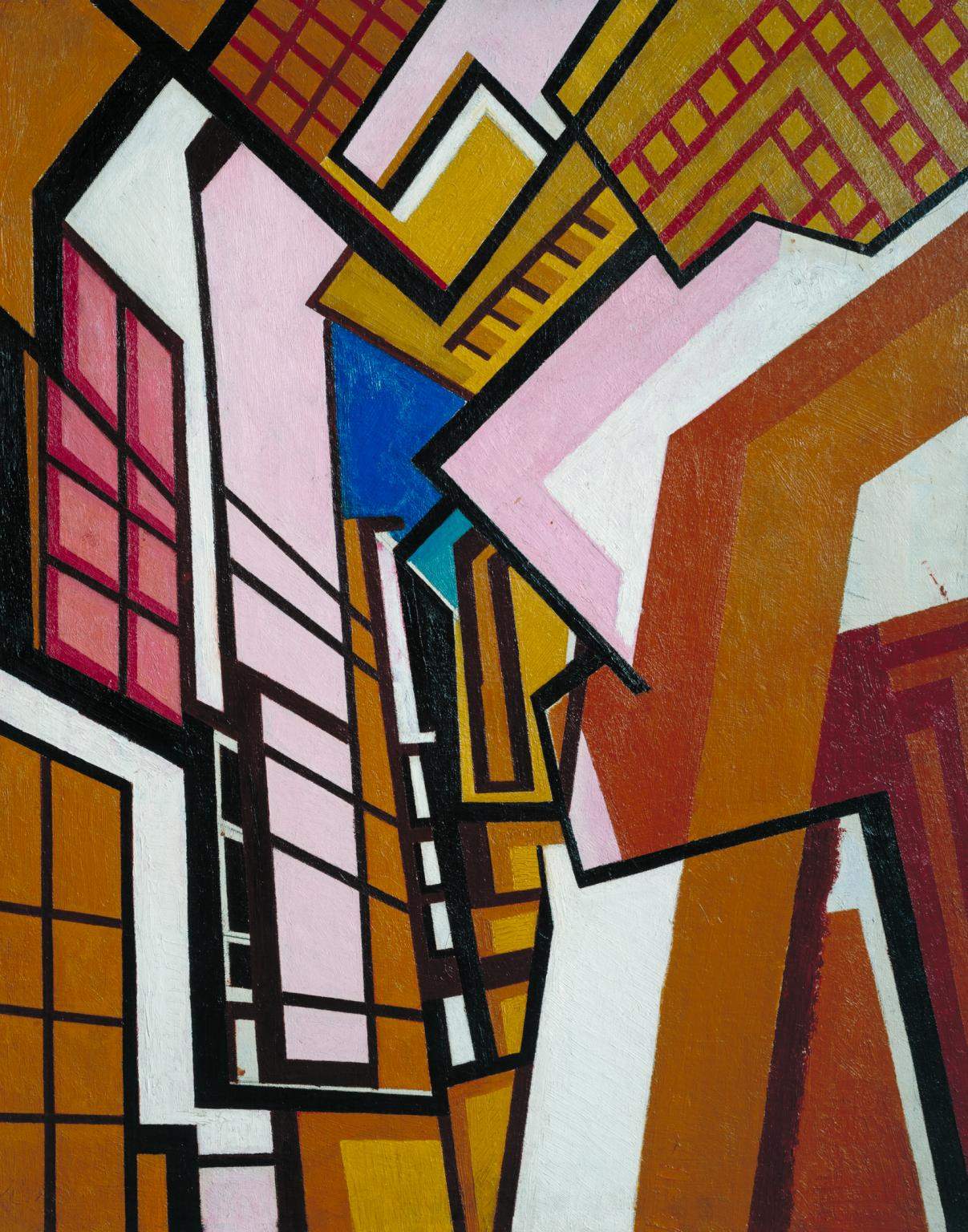

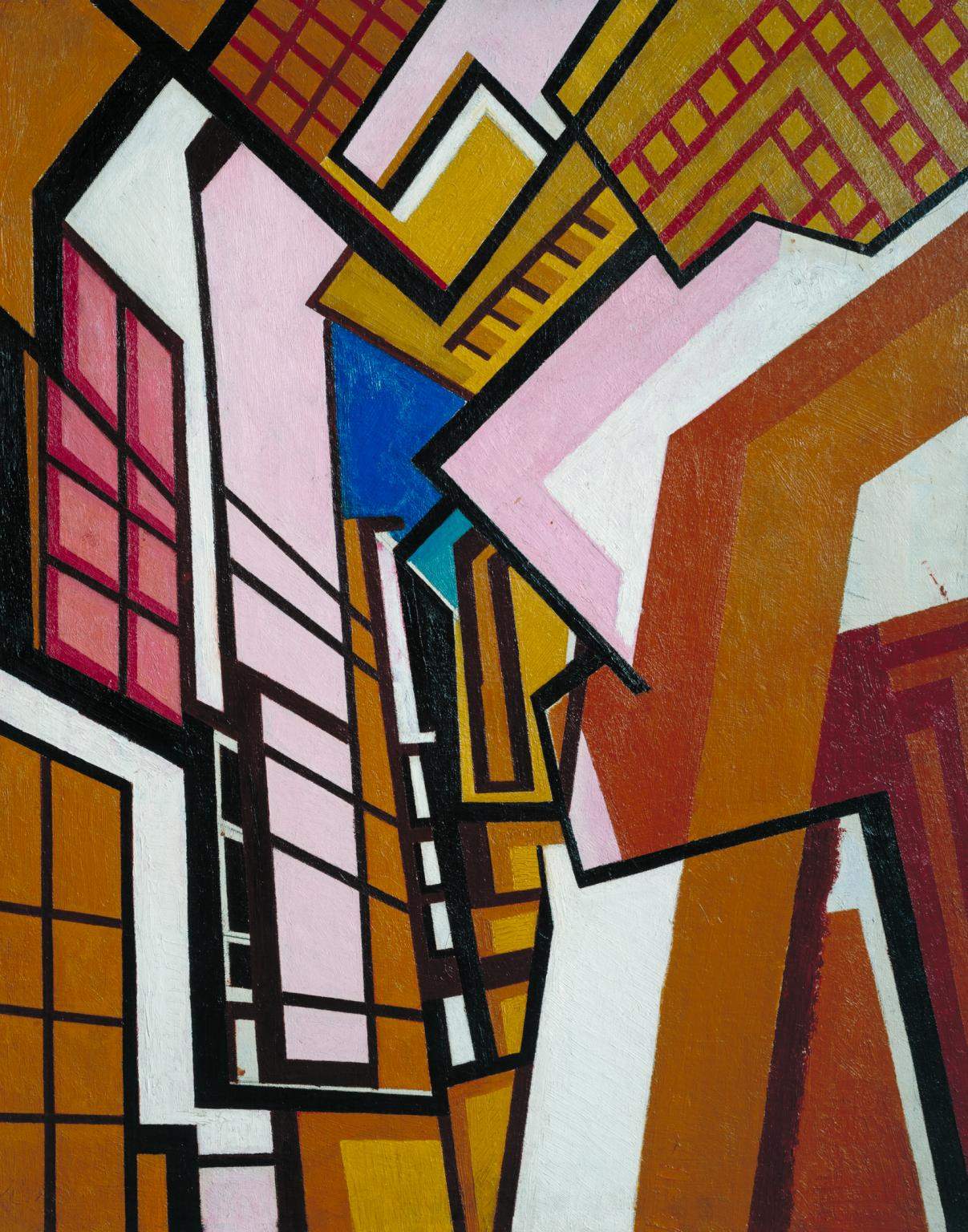

As a founder, Lewis was instrumental in developing the aesthetic thrusts that characterized the movement; his oil on canvas work Workshop of 1914-15 demonstrates Vorticism’s abstract geometric style and clarity of vision. Vivid lines and colors create a swirl of pushed planes. The title suggests that the painting represents a physical space, but it is difficult to distinguish whether it is an indoor or outdoor space. It could be a cityscape, perhaps an industrial London, or the interior of a studio, with the sky seen through a skylight. The sharp angles and loud colors were an assault on traditional composition and harmony. This work of his along with several others demonstrate the need for comparison between static and dynamic elements in the painting. Jessica Dismorr, too, in her Abstract Composition, oil on wood of 1915, made a series of geometric shapes in pastel colors on a black background that suggest a vision of a series of rigid architectures overlapping and seeming to float alongside one another. In the second issue of Blast, Dismorr described London as “towers of scaffolding drawing their crisscrossing pattern of bars in the sky, a monstrous tartan.”

The choice to render the vitality of the urban environment and bodies is well expressed in drawings such as Helen Saunders’s Dance (c. 1915) and in sculpture, for example, in Gaudier-Brzeska’s Red Stone Dancer of 1913, where the artist abstracts a dancer’s body into large planes organized in such a way that they appear to twist around each other. Suggesting the figure’s movement, despite the solid, static feel of the stone, the artist expressed his guiding concept: “Movement is the translation of life, and if art depicts life, movement should enter art, since we are aware of life only because it moves.”

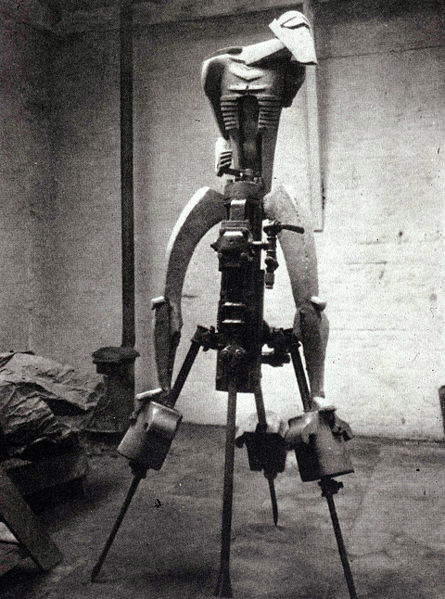

Also from 1913 is a pivotal work by sculptor Epstein, who, although he did not subscribe to the Vorticist manifesto, presented evolutions that were closely related to it at the time: The Rock Drill (“The Rock Drill”), had begun as a celebration of the union of man and machine, a hybrid that anticipated humanity’s future as cyborgs, but was disrupted by the artist’s awareness that machines and machinery had wreaked havoc in World War I. Epstein initially created a plaster cast of a human body straddling an industrial mining drill, which was to be between 2 and 3 meters tall indicating the frightening but exciting possibilities of that industrial age. But after experiencing the horrors of war, he abandoned the positive idea of the machine as a human aid and transformed the work, truncating the human figure and removing the drill, into a limbless mutilated torso cast in bronze and presented on a pedestal. A “pure form,” which, as in abstract painting, alluded to the distilled essence of its subject, powerless and defeated by the mechanics of war. Epstein’s vision of the future of humans and machines had changed as it had for many of the members of the Vorticist movement, demonstrating the parabola, the rise and fall, of futurist aesthetic ideals at the turn of the century.

|

| Vorticism. History and style of the English davantgarde movement. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.