Vasily Kandinsky, between Spiritual and Abstractionism. Life, works, treatises

Figurative painting reigned supreme from the Renaissance until 1910, the year when the Russian artist, Vasily Kandinsky (Moscow, 1866 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1944) gave birth to the world-famous First Abstract Watercolor, considered to be the first work of abstract art in art history (although, as will be seen below, a recent debate on the birth of abstract art may take the primacy away from him). What Kandinsky conceives is not a mere doodle, as a first-time observer might think, but rather testifies to the artists’ need to go beyond objectivity, moving away from that real dimension that makes one image trace back to another. In those years, important changes were taking place in art, especially in the relationship with patrons: artists, for centuries bound to more or less large commissions and free to deal with the subject only up to a certain point (if not responding to precise needs), from the nineteenth century had begun to claim their total freedom of expression. Thus we see a progressive evolution, the roots of which lie in previous centuries.

If in the eighteenth century it was clothes, family crests, and jewelry that characterized portraiture, already with Francisco Goya (Fuendetodos, 1746 - Bordeaux, 1828) a new sensitivity to human individuality emerged. During the nineteenth century the individual began to occupy an increasingly central and fundamental place in artistic research; feelings, the human psyche, were investigated, and studies on psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud (Freiberg, 1856 - Hampstead, 1939) became decisive. While fidelity to figuration is maintained in the nineteenth century, however, it is with Kandinsky ’s watercolor that a more pronounced departure from traditional painting takes place, although, as mentioned, recently the primacy of the Russian painter is being challenged in a debate about the birth of abstract art(read an in-depth discussion on the birth of abstractionism). The artist, however, does not just present his work, but also wants to explain the reasons for abandoning figuration. This is the period of the great treatises, born to explain and motivate choices and stances. Kandinsky, who will always combine his artistic activity with a conspicuous treatise activity, is not alone; he is surrounded by colleagues who agree to put an “end” to a figuration now felt to be no longer obligatory, and which had alienated the artist from his own needs. Along the same lines as him ran the researches of Piet Mondrian (Amersfoort, 1872 - New York, 1944) and Theo van Doesburg (Utrecht, 1883 - Davos, 1931), the two founding fathers of Neoplasticism. The researches of great artists such as František Kupka, Kazimir Malevič, László Moholy-Nagy, Franz Marc, and Paul Klee, also ran parallel; although they were all different artists with different personalities, they were united by the desire to break the link with tradition in order to achieveabstraction. As evidence of a varied and complex artistic panorama, it is worth mentioning that in the same years Giorgio De Chirico’s Metaphysics was born in Italy, a movement, technically speaking, extremely linked to the figurative dimension, although the reality represented is rarefied and deformed as well as inhabited by unusual objects.

Finally, it should be mentioned that most of the named artists were forced to emigrate, from Germany where their researches had found fertile ground (the same goes for Kandinsky, who was present in Germany until 1933), to less hostile territories in the years leading up to World War II, roughly between 1933 and 1939, since with the advent of Nazism non-figurative art was condemned as degenerate art. In this regard, in 1937, the Entartete Kunst exhibition was held in Munich to denounce all art that did not adhere to the figurative standards imposed by the regime (abstract art obviously did not fit in, so many works were withdrawn, seized and sold or destroyed: read a detailed discussion of degenerate art according to the Nazis here).

|

| Vasily Kandinsky in 1905 |

Biography of Kandinsky. From first abstract watercolor to teaching professorship at Bauhaus

“At one time, the painter was looked at sideways if he wrote-even if it was letters. One almost wanted him to eat, even, with his brush, instead of with a fork” (Vasily Kandinsky, My Wood Engravings, 1938).

Known as the father ofabstractionism, Vasily Vasil’evič Kandinsky was born in Moscow on December 16, 1866, to a wealthy merchant family that moved to Munich in 1870. He began drawing as a child, following a trip to Venice, but went on to earn a law degree in 1892 although in 1896, after graduating in law, he decided to give himself to art instead: that year he therefore enrolled at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, where he was a student of Franz von Stuck. In 1889, while studying law, he had been commissioned to conduct research on rural Russia-a formative background that the artist would always carry with him. In 1901 he founded the Phalanx group, which promoted Jugendstil art, and the following year exhibited for the first time with the artists of the Berlin Secession. In 1903 he made a trip to Italy and then went to Russia, and again in 1904 he exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in Paris. Instead, it was in 1908 that he bought his house in Murnau, Bavaria, which was to become a meeting place for artists, and where he began to make his first abstractionist experiments.

In 1909 he joined the Neue Künstlervereinigug München, New Association of Artists in Munich, dissatisfied with the rarefied secessionist climate, which was too close to Impressionist solutions and not very tense toward modernity. Kandinsky began to conceive of his works by impressions, compositions and improvisations, three categories derived from the emotional-interior sphere that the artist, according to Vasily, necessarily had to take into account. His theories converge in his writing The Spiritual in Art, conceived in 1910 and published in late 1911. It is the first treatise to deal with abstraction, through the study of the perception and effects of color in the viewer and, of course, in the artist. These effects are not to be charged by external elements, but by inwardness, deep and pure. The treatise justifies Kandinsky’s choices to abandon figuration. In 1911, the artist was struck by the writing Handbook of Harmony, by composer Arnold Schoenberg, with whom he would end up establishing a deep friendship (read also an in-depth look at the relationship between Kandinsky and Schoenberg). Kandinsky decided to write him a letter: it was the beginning of a series of correspondences between the two, who would come to talk about dissonances in art, thoughts not without contradictions, but fundamental as a starting point for modernity.

In 1911 Kandinsky founded the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group together with artist Franz Marc, thus breaking away from the New Association of Artists. It was a brief (lasting from 1911 to 1914) but effective experience, expressing the lives of the artists who joined it; in addition to them, the Austrian Alfred Kubin, the Swiss Paul Klee, the Germans August Macke and Gabriele Münter, and the Russian Alexej von Jawlensky were members. The group pursued all areas of artistic, musical, poetic and graphic research, hence the idea of totalizing art to which Vasily adhered. A second Russian period began in 1914, which provided the artist with further insights into his work, but simultaneously put Kandinsky, whose art was not appreciated in his homeland, in a bad light. In 1922 the artist settled in Berlin, where two solo exhibitions of the artist were organized, one at the Goldschmidt-Wallerstein gallery and the other at the Thannhauser in Munich. In the same year he moved further and further away from the Russian Suprematist avant-garde, abandoning the ruler and straight lines forever. In the 1920s he was called as a teacher at the Bauhaus school in Weimar, founded by architect Walter Gropius, where Kandinsky taught theory of form and a practical workshop in mural painting. Summarizing the courses taught here is the 1926 treatise Point, Line, Surface where the artist turns his attention to the psychological aspects of color within pictorial representation. The paper is elaborated at a time when the Bauhaus headquarters was being moved to Dessau. In elaborating it, Kandinsky took into account the innovations brought by the theories expressed by art historian Wilhelm Worringer in Abstraction and Empathy, but not only that: the two also collaborated on some writings. In 1933 the Bauhaus school was forced to close due to the hostilities of the Nazi regime. An artist, theorist, teacher, and music lover, Kandinsky nevertheless fell on the lists of artists whose art was considered degenerate by the Nazi regime: so Kandinsky, then almost 70 years old, moved to Paris where he remained until his death in Neuilly-sur-Seine on December 13, 1944. Abstractionism would not come to an end with Kandinsky’s death: artists of new generations would carry on the discourse he had undertaken, such as the current ofAmerican Abstract Expressionism, whose greatest exponent Jackson Pollock, inventor of dripping, a painting technique in which the artist’s gesture is subordinated to the inner emotional trend.

|

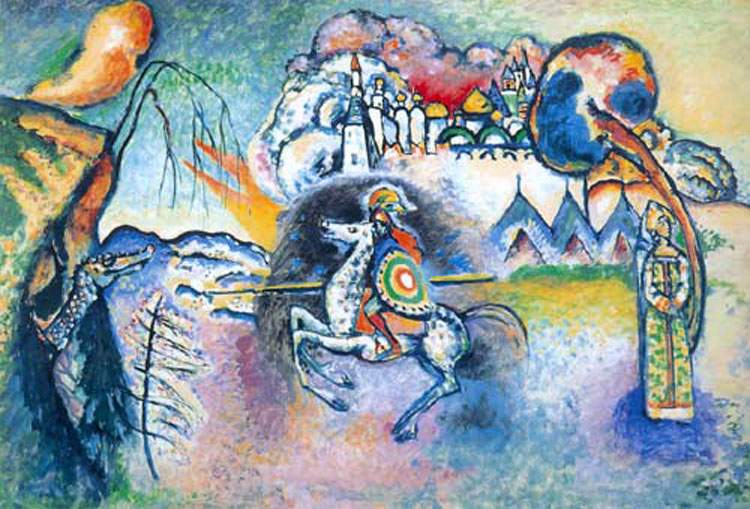

| Vasily Kandinsky, The Knight (St. George) (1914-1915; oil on cardboard, 61 x 91 cm; Moscow, Tretyakov Gallery) |

|

| Vasily Kandinsky, Composition 8 (Komposition 8) (1923; oil on canvas, 140.3 × 200.7 cm; New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) |

|

| Vasily Kandinsky, Yellow-Red-Blue (1925; oil on canvas, 128 × 201.5 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) |

Art and key works

The experience of the Balue Reiter arouses in Kandinsky interest in a pure originality, a primitive art, linked to the simple spontaneity of the childlike world (“Every art,” Kandinsky writes in The Yellow Sound published in an issue of the almanac The Blue Rider, “has its own language, that is, its own particular and exclusive medium. Every art is therefore something concluded. Every art has a life of its own. It is a realm of its own.”) The First Abstract Watercolor recalls, visually speaking, the playful dimension of children, because the primal instinct is itself spontaneous and pure. However, Kandinsky’s departure from figuration is progressive. The First Abstract Watercolor is a turning point for art history, starting with the technique, since the use of watercolor had always been considered secondary to tempera or oil painting, but also to preparatory sketching. What intrigued Kandinsky were the possibilities the technique offered: consisting of substances diluted then in water, it offered the possibility for artists to achieve transparencies, enhance luminosity, through muted colors. The Russian painter would continue to make works far from figuration until the end of his existence. Kandinsky’s main influences lie in his gaze toward the Symbolists, but also of the works of Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and are mindful also of the dramatic decomposition of German Expressionism. But if in the eyes of us contemporaries his art is appreciated, on the contrary the critics of the time attacked Kandinsky often even viciously. There were two positions taken toward him: one of appreciation and admiration for the innovative scope of his art, the other of contestation and contempt. The artist repeatedly accused of making cold works without logical meaning by his contemporaries; if the death blow came from the Nazi regime, consecrating his art (and that of many other great artists) as degenerate, he never stopped painting, continuing to convey the ideals of a non-figurative simplicity.

Kandinsky also allowed himself to be influenced by sources outside the world of the visual arts, starting with music. During his lifetime, in fact, he maintained correspondence relations with the composer Arnold Schoenberg, a fundamental testimony to reconstruct the salient moments in the evolution of the artist’s thought. The painter had been playing the cello since childhood, not surprisingly integrating the musician’s discoveries about dissonance into his conception of art. The two established a friendship, which was interrupted with the outbreak of war. The musical influence was so important that it can be put on the same level of importance as those derived from the visual arts. Kandinsky’s project was to give rise to evocative art, capable of moving away from the observation of reality and settling on the plane of states of mind, where analogies between musical notes and colors are fundamental (for the Russian artist, colors, as well as notes, correspond to states of mind): “Problems great and small in painting,” Kandinsky writes in his seminal book The Spiritual in Art, “will depend on interiority. The path we take, and which is our greatest fortune, will lead us to rely no longer on exteriority, but on its opposite: inner necessity.”

|

| Vasily Kandinsky, First Abstract Watercolor (1910; Watercolor, pencil and India ink on paper, 49.6 x 61.8 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) |

|

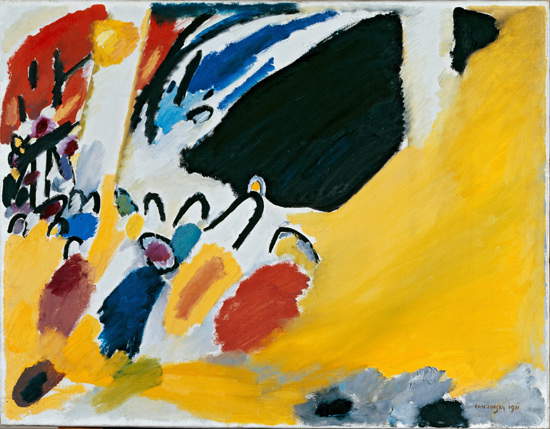

| Vasily Kandinsky, Impression III (Concert) (1911; oil on canvas, 77.5 x 100 cm; Munich, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus) |

|

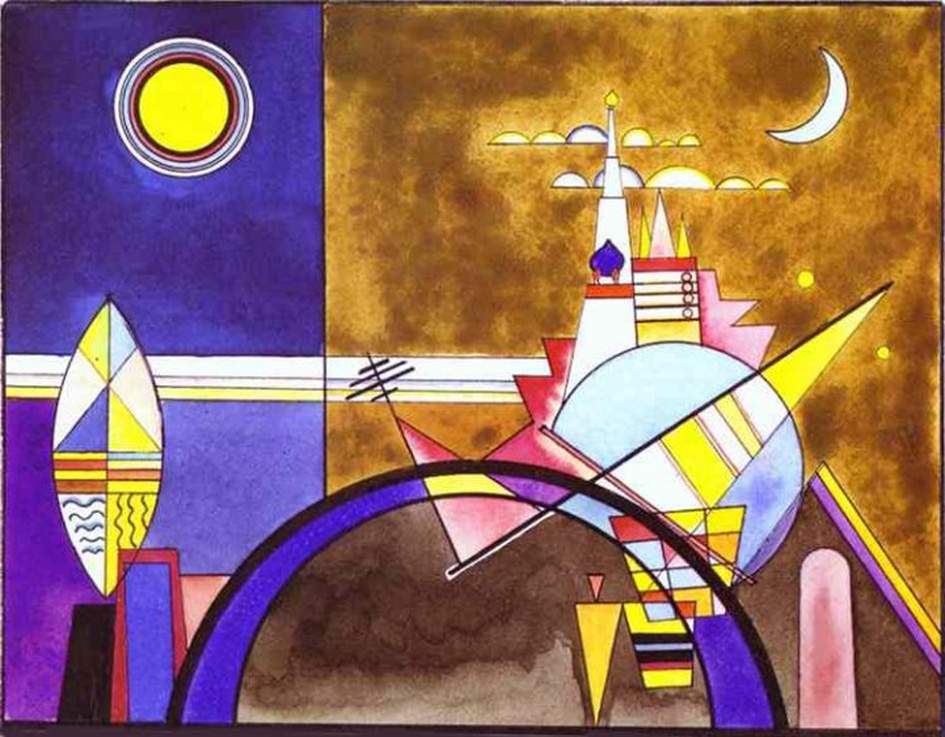

| Vasily Kandinsky, Bühnenentwürfe zu Musorgsky (1928; tempera and watercolor on paper, 21.2 x 27.3 cm; Cologne, Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung Schloss Wahn) |

Where to see the works of Vasily Kandinsky

There are several works by Kandinsky in Italy. To see them, one must go to the GaMeC in Bergamo and the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, where Angular Line, among the most significant examples of abstractionism, is preserved. Kandinsky is also present in Venice, at the Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna Ca’ Pesaro and in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, where several works from the period 1913-29 are housed. Still in Milan, at the Museo del Novecento, and at the Mart in Rovereto, some of the Russian painter’s works can be admired: in particular, no less than five works and a watercolor from 1925 are at the Mart.

Abroad, his works can be found in several countries, but at the Lenbachhaus in Munich many of the artist’s works are preserved, particularly from the Blue Rider period. Other important works are at the Russian State Museum and Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Tret’jakov Gallery in Moscow. Another museum that holds a good number of Kandinsky’s works is the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

The person who collected Kandinsky’s works early on was one of the founding fathers of the Guggenheim Foundation, Solomon R. Guggenheim, who began acquiring works by Vasily as early as 1929, enabling him to accumulate a considerable number of them. The Guggenheim in Bilbao, between 2020 and 2021, has organized a major retrospective exhibition dedicated to the artist, as part of which it has also launched a virtual tour that can be reached through the institution’s website. Recently, the Google search engine launched a new app called Play a Kandinsky, so you can hear the sounds of the colors in his works.

|

| Vasily Kandinsky, between Spiritual and Abstractionism. Life, works, treatises |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.