“I would like to erase all the values I knew that I know and am losing sight of, to redo, rebuild on a new basis! All the past, wonderfully great, oppresses me I want new! And I lack the elements to conceive where one is at, and what one needs. With what to do this? with color? or with drawing? with painting? with verist tendencies that no longer satisfy me, with symbolist tendencies that I like in few and have never attempted? With an idealism that I do not know how to concretize?” When Umberto Boccioni (Reggio Calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916) wrote these lines, on March 14, 1907, the artist, among the leading exponents of Futurism, was going through one of several moments of crisis in his short career, which lasted just nine years but was among the most important in the entire history of art. Boccioni at that time was only twenty-five years old and was already revealing his temperament: that of a constantly dissatisfied artist, but also of a profoundly “rebellious” nature, one might say, which fueled his propensity for continuous experimentation, his openness to the new, and his desire to investigate some of the age-old problems of art history.

Umberto Boccioni’s parable fits fully into that of futurism, a movement that stood in contrast to traditional culture, rejecting “passatism” and academicism, proposing the intent to eliminate all the values of previous culture in order to give rise to a completely new art capable of obliterating all the old forms of expression, perceived as stale and outdated: an art that, in essence, celebrated modernity, speed, the dynamism of city life, and technological development. Intents that the Futurists also expressed through their various manifestos: it was February 5, 1909, when Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Alexandria, Egypt, 1876 - Bellagio, 1944) published, in the Gazzetta dell’Emilia, the Manifesto of Futurism (the publication in Le Figaro, on the other hand, dates back to February 20: the latter is the date that is most often remembered in art history textbooks since at the time the center of art was Paris and the publication of the manifesto in the French newspaper naturally had a much wider resonance). Famous is the sentence in which Marinetti states, “A racing automobile with its hood adorned with large snake-like tubes with explosive breath...a roaring automobile, which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace,” which is often quoted to give a sense of the futurists’ aims.

Within the movement there were different stylistic orientations, of course. Thus, if Giacomo Balla was much influenced by Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s photographic experiments, if Gino Severini, as a Tuscan, provided the most delicate and light interpretation of Futurism, if on the other hand Fortunato Depero was the most playful Futurist, Umberto Boccioni was of the movement the most dramatic, the most tormented, one of the most radical and incendiary, and he was the futurist who, in the field of sculpture, achieved the most modern and innovative results, so much so that he could be considered as the artist who opened the twentieth century, thanks above all to one of his greatest masterpieces, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. The most original results would be those that Boccioni achieved only in the last six years of his career: six years, however, that probably changed the course of art history.

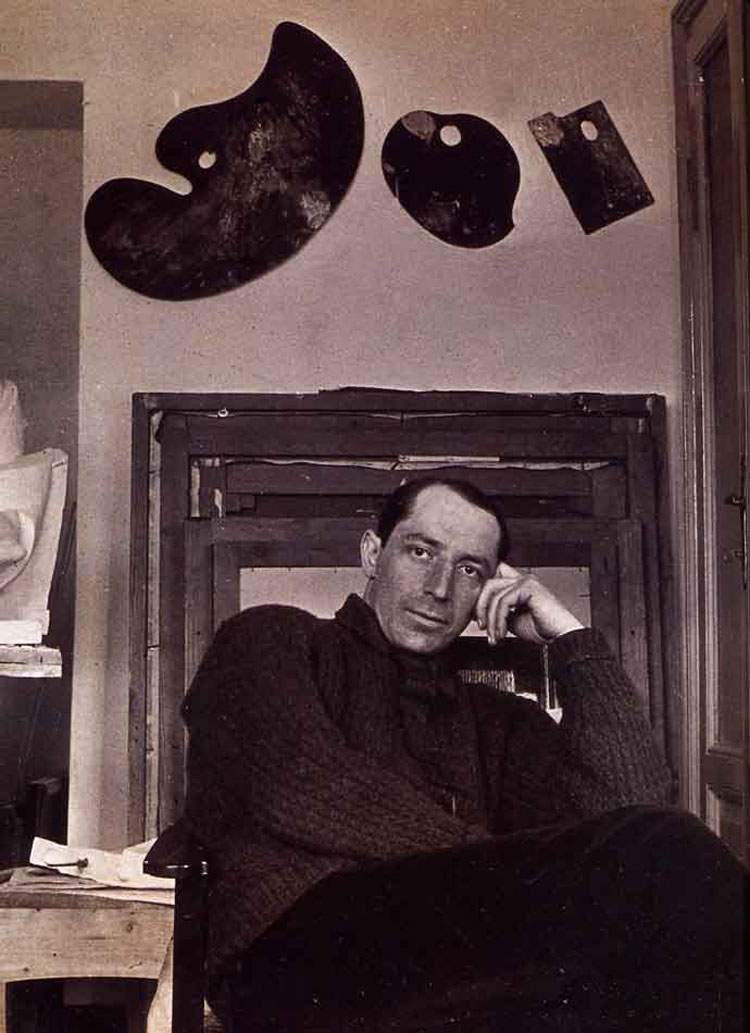

|

| Umberto Boccioni in 1914 |

Umberto Boccioni was born 1882 in Reggio Calabria to Raffaele, a prefecture clerk originally from Morciano di Romagna who was in Calabria for work, and Cecilia Forlani. In the early years of his life the artist moved to different cities in Italy (Genoa, Padua, Catania) following his father’s work, and graduated from the 1897 Istituto Tecnico di Catania. Boccioni initially nurtured literary aspirations, so much so that he wrote a novel, Pene dell’anima (of 1900), which, however, remained unpublished. In 1901 he moved to Rome and here began a timid artistic activity as a poster artist. At the same time he began to paint after meeting Gino Severini: the two attended the atelier of the older Giacomo Balla and then decided to enroll in the free school of the nude at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome. After exhibiting at a group show at the Teatro Nazionale in Rome in 1905, he managed to get his parents to pay for a trip to Paris in 1906: on his return, he decided to enroll at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, but abandoned it to move to Milan in 1907, where he attended Romolo Romani and Gaetano Previati, and where he met Marinetti and other Futurist artists.

A key year for Boccioni’s biography is 1910, when, in addition to painting some of his masterpieces such as La città che sale or Rissa in galleria, he signed with Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painters, which Boccioni himself read on May 8 of that year at the Politeama Chiarella in Turin. He began to paint his first major works, and again in 1910 he exhibited them first in the spaces of the Famiglia Artistica in Milan, then in Venice, at Ca’ Pesaro, in an exhibition set up by Nino Barbantini, who organized a show of no less than 43 works for him. In 1911 and then again in 1912 he was again in Paris where he exhibited his works, and also in 1912 he published the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture, exhibiting at the Salon d’Automne. Having meanwhile become a contributor to the magazine La Voce, he also became the soul of the celebrated Futurist evenings, which often ended in brawls due to the provocations and incendiary passion of the Futurists.

In 1914, on the brink of World War I, Boccioni was a fervent interventionist and even participated in some demonstrations (even being arrested in Bologna in the fall). Still in 1914, together with Carrà, Boccioni, Marinetti, Russolo, and Ugo Piatti he signed the Futurist Synthesis of War manifesto, while the Italian Pride manifesto, signed together with the same artists, Mario Sironi, and Antonio Sant’Elia, was in 1915. In May, Boccioni enlisted as a volunteer, and in November, his experience on the front having ended, he returned to Milan where he resumed his activities (in addition to painting and sculpting, Boccioni wrote extensively in various magazines). He returned to the war in July 1916 and was assigned to the Verona artillery regiment: he died on August 17, 1916 in the military hospital in Verona, following a fall from his mare in which he had been seriously wounded. He is buried in Verona’s Monumental Cemetery.

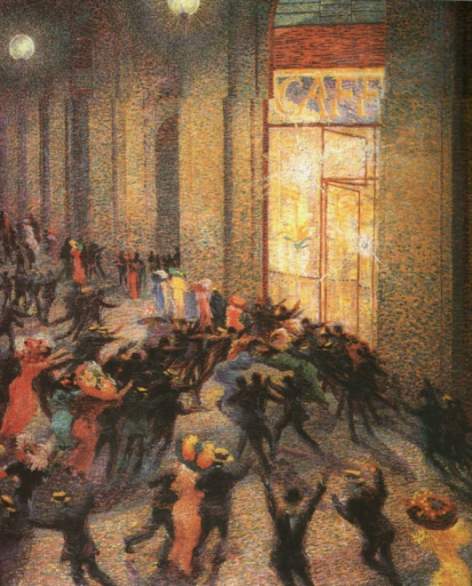

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Rissa in the Gallery (1910; oil on canvas, 76 x 64 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento) |

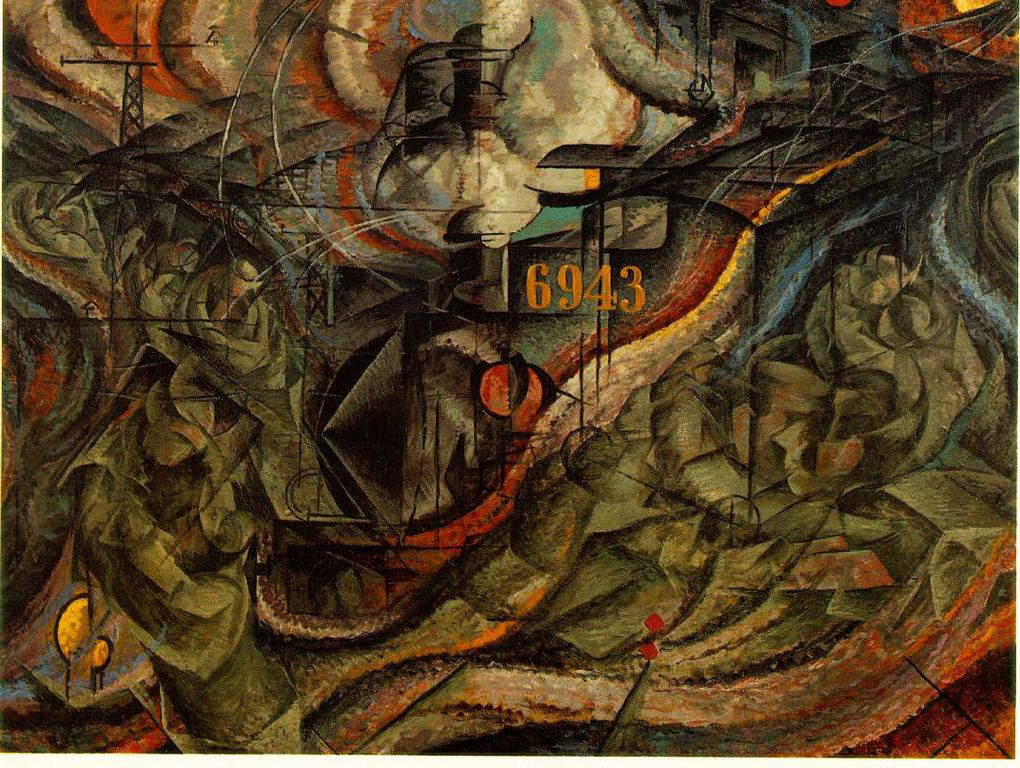

|

| Umberto Boccioni, The Rising City (1910; oil on canvas, 199.3 x 301 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913, cast in bronze, 1931; bronze, height 126.4 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento) |

Boccione’s early art is, from 1907 to 1910, still very much linked to divisionism within which the artist asi formed, following Giacomo Balla (see, for example, The Mother, a pastel preserved at the Galeria d’Arte Moderna in Milan). In addition to the experiences that could be more closely compared to Divisionism, Boccioni, caught up in his constant research, also juxtaposed a lesser-known production of an expressionist type, indebted to the research of Munch. The perspective, however, changed completely in 1910, when the artist signed with his colleagues the Technical Manifesto of the Futurist Painters, which read, among other resolutions: “The gesture, for us, will no longer be a stopped moment of universal dynamism: it will be, decisively, the dynamic sensation eternalized as such. Everything moves, everything runs, everything turns quickly. A figure is never stable before us, but incessantly appears and disappears. Because of the persistence of the image in the retina, things in motion multiply, deform, following one another, like vibrations, in the space they run through. Thus a running horse does not have four legs: it has twenty, and their movements are triangular. Everything in art is convention, and yesterday’s truths are today, for us, pure lies. We affirm again that the portrait, to be a work of art, cannot and must not resemble its model, and the painter has in himself the landscapes he wants to produce. To paint a figure one must not make it; one must make an atmosphere of it.”

The masterpiece that best represents this phase is La città che sale: on a substrate that is still fundamentally symbolist, Boccioni grafts a violent chromatic whirlwind, painted with fragmented brushstrokes that impart a strong sense of movement to the scene. The Rising City is also one of the earliest Futurist masterpieces, as well as Boccioni’s first fully Futurist painting, the first to introduce a much more dynamic vision of the subject (which in this case, as is often the case in Boccioni’s painting, is nothing more than a view of a city). Boccioni had arrived at this tension after coming very close with works from the same period: Rissa in the Gallery, for example, is from 1910, is still a work deeply linked to Divisionism, but a component of movement is already introduced that forms the basis for the masterpieces of the next phase.

With the States of Mind of 1911, Boccioni’s painting has already been radically renewed and arrives at a mode of expression in which colors, contrasting tones, forms, space, expressionist-like deformations, and movement combine to give rise to swirling compositions, where space is dilated and where lines contribute to suggest the tension of the scene (in The Farewells, one of the canvases that make up the first States of Mind series, the sensation the artist communicates is that of a moving train, with the locomotive appearing behind a chaos of lines and shapes that suggests not only the movement of the vehicle but also the confusion of the station). The theme of movement is then further developed in such work as Dynamism of a Cyclist and Dynamism of a Footballer, which go in search of the “dynamic manifestation of form,” to use an expression of the artist.

It has been said that one of the main subjects of Boccioni’s research is that of the mother, very present in his early works, but also present when Futurist research was in full swing: this is seen, for example, in Materia, a famous “Futurist” portrait of Boccioni’s mother. A staordinarily modern portrait that finds in the reflections of Paul Cézanne the starting point for the simplification of space and is nourished by Picasso’s suggestions, Materia is a work that, Marisa Dalai Emiliani has written, “peremptorily camps on this side and beyond the canvas, on this side and beyond the transparent double diaphragm of a dematerialized window (but an inescapable reminder of Alberti’s metaphor of Painting) and in the pierced arabesque of the railing, which the lines-force of its volumes cross and by whose planes they are interpenetrated.” That of lines-force is one of the key concepts of Boccioni’s aesthetics: they are the means by which Boccioni decomposed his figures by constructing his forms in motion, to arrive at the “representation of the motions of matter in the trajectory that is dictated to us by the line of construction of the object and its action.” “What we want to represent,” he had to write, “is the object in its dynamic experience and to give the synthesis of the transformations that the object undergoes in its two relative and absolute motions. We want to give the style of movement. We do not want to transport in image we identify with the thing. So for us the object has no a priori form. But only the line of its weight and expansion is definable. This suggests to us the force lines that characterize the object and lead us to understand the main essence of the object this the intuition of life.” The artist also employs force-lines in what is perhaps his main masterpiece, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, the work with here the artist “conquers” space by opening to the fourth dimension that will later be definitively conquered by Lucio Fontana, who will see in Boccioni a kind of ideal father.

|

| Umberto Boccioni, The Mother (1907; pastel on paper applied to canvas, 72 x 80 cm; Milan, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Raccolta Grassi) |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, States of Mind I. Farewells (1911; oil on canvas, 71.2 x 94.2 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Matter (1912; oil on canvas, 226 x 150 cm; Mattioli Collection, on deposit at Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice) |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913; oil on canvas, 70 x 95 cm; Mattioli Collection, on deposit at Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice) |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Development of a Bottle in Space (1912; bronze, 38 x 59 x 32 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento) |

The main masterpieces are kept in several museums in Italy and abroad: while it is relatively easy to see the unique Forms of Continuity in Space (the original in plaster is kept at the Museum of Contemporary Art in São Paulo, Brazil, but there are several posthumous bronze castings, one of which is kept at the Museo del Novecento in Milan), it is not so easy to see some key masterpieces (for example, La città che sale and Gli addii mentioned above are at the MoMA in New York). However, wanting to point to two museums to get a first “smattering” of Boccioni’s art, one can mention the Museo del Novecento in Milan and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice.

The Milan museum has dedicated a room to Boccioni, thanks to which it is possible to broadly reconstruct his path, which is well represented by paintings from different periods. There is, for example, Mrs. Virginia, a quiet portrait from 1905, there are The Farewells from the second series of States of Mind, Elasticity from 1912, Under the Bower from 1914, and then also a highly relevant sculpture such as Development of a Bottle in Space and the aforementioned posthumous fusion of the Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. At the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, on the other hand, it is possible to find Matter and Dynamism of a Cyclist, both here on deposit from the Mattioli collection, the sculpture Dynamism of a Horse In addition, at the end of 2020 the Umberto Boccioni Museum was founded in Morciano di Romagna, the homeland of the Boccioni family, awaiting to find a permanent home: here a good documentation on the early years of the great Futurist artist is gathered.

What we want to represent is the object in its dynamic experience and give the synthesis of the transformations that the object undergoes in its two relative and absolute motions. We want to give the style of motion. We do not want to transport in image we identify with the thing. So for us the object has no a priori form. But only the line of its weight and expansion is definable. This suggests to us the force lines that characterize the object and lead us to understand the main essence of the object this the intuition of life

|

| Umberto Boccioni: the life and works of the great futurist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.