Transavantgarde was an artistic movement that arose and developed inItaly in the early 1980s, achieving conspicuous success. The emergence of this artistic movement entailed a return to figurative, citationist painting with neo-expressionist ancestry. The artistic expression of the Transavantgarde always had a pointed eye toward the past, a past that it wanted to revisit and reinterpret in the full style of a “return to order.”

This artistic mode certainly had a major impact on Italian art, but it also resonated internationally, contributing to the rediscovery of painting technique and figurativism after a period, the 1970s, that had experienced the artistic dominance of the idea, of the concept. For example, in the United States, this trend suffered the legacy of the imposing pop culture, and thus resumed its more typical figuration.

It was the critic Achille Bonito Oliva who designated the features of this new current, first writing about it in an article in 1979 and then in 1982, in more detail, in his work Avant-Garde Transavanguardia. The Transavanguardia experience was short-lived, and the grouping of painters who had adhered to this artistic attitude was always unofficial, as each of them developed a very independent poetics and style. Because of these expressive diversities, the artists pursued their careers separately, but without coming to an effective dissolution of the group.

With the term Transavanguardia born in the Italian art scene in the early 1980s, a new type of expressionism was emerging, adopted to indicate a return to figurative painting and a recourse to the traditional artistic techniques of drawing, painting, and sculpture. Technically, the pictorial style pursued was deliberately crude, strong, and subversive. By virtue of the latter aspect there were other names, such as bad painting and dumb art; but also new image painting, highlighting a return of images and icons. In this artistic declination of the late twentieth century, it became possible to combine a naive expressive framework (precisely, dumb) with a post-conceptual dialectic. However, the regressive charge inherent in the revival of figure painting allowed a pictorial inflection toward a direct, expressively immediate style.

To the figure of Achille Bonito Oliva (Caggiano, 1939) we owe the invention of the term and the theorization of the movement, thus also the foundation of the group, of which he was a critic-manager. The neologism was intended to indicate the hybrid, trans-cultural and trans-historical nature of a language that aimed to mix moments and characters of even very different artistic traditions. It was above all a citationist style, characterized by nomadism. As can be deduced from the term, the Transavantgarde wanted to traverse the Avant-gardes, going beyond them to open itself to the possibility of experimentation, maintaining a retrospective gaze while inventing new stylistic combinations and solutions to probe the artistic legacy accumulated up to that time. The Transavantgarde artist could rely on the various texts of the past and combine them, even resorting to the use of popular materials, such as comics or advertising. This process was carried out in complete freedom, and at the same time allowed for the expression of the unconscious component of the creative act, drawing on the aestheticizing and playful aspect of the act of painting. For this reason, it can be said that Transavantgarde drew on both Surrealism andExpressionism.

On these tracks and under the new label of Transavanguardia traveled the five Italian artists named by critic Bonito Oliva in 1979, in his article published in “Flash Art” (nn. 92-93): Enzo Cucchi (Morro d’Alba, 1949), Mimmo Paladino (Paduli, 1948), Sandro Chia (Alessandro Coticchia; Florence, 1946), Francesco Clemente (Naples, 1952), and Nicola de Maria (Foglianise, 1954), who were united by their rejection of an ideologized and political art and their rejection of a linear conception of progress, as was typical of the historical avant-garde and post-modern man.

From the study of the poetics of these authors, there emerges a particular interest in the figure and work of the metaphysical artist Giorgio de Chirico, that is, the first to employ expressive languages by taking them backwards in the History of Art. To explain the production of Transavantgarde artists, Achille Bonito Oliva used the metaphor of the “seeing blind man”: according to this, the artist shatters the lenses that make his a unified vision. So he looks around with a fragmentary, kaleidoscopic gaze. In this way, he becomes able to grasp elements that are distant from each other and tries to bring them back to a principle of balance and harmony. The Transavantgarde artist, therefore, had a distrustful attitude toward history, did not propose chronologically identifiable models, but transcended cultural and geographical boundaries to create his own imagery, absolutely arbitrary, in which he was free to insert autobiographical experiences and memories.

Transavantgarde, in transcending the conceptuality inherent in the work of art, dragged along the suggestions of Arte Povera and Conceptual Art. Since its founding, critic Achille Bonito Oliva has been at pains to point out what differences existed between the movement of which he was theorist and the artistic trends dominating the Italian scene. Despite the conscious distancing, some common areas can be identified, especially with Arte Povera. In fact, the five Italian artists indicated by the critic all had direct experiences with those modes of operation, or at least worked in close contact with the major exponents of those currents. From a formative point of view, these were decisive cultural exchanges, and it was natural that they were affected by those suggestions in the continuation of their careers. Moreover, the publicity operation carried out by the critic Germano Celant was comparable to the one carried out by Oliva for the Transavanguardia: both are distinguished as initiatives carried out to impose themselves as a novelty, an avant-garde solution with its own distinct characters.

Other common aspects are the critique of Darwinian positivism and the notion of progressivism, the openness attributed to the concept of uncertainty and that of complexity; the importance given to tradition and craft, the anti-intellectualism. So, the general opposition to earlier artistic production converged with the revival of traditional techniques. In a very few years, the five exponents managed to touch considerable market quotations and become pioneers, the object of imitation by artists from all parts of the world. However, it becomes somewhat difficult to identify the traits that united the Transavantgarde artists themselves. For example, Nicola de Maria distinguished himself by being a predominantly abstract painter, while Sandro Chia and Francesco Clemente aimed for a predominantly figurative line. A major innovation of the Transavanguardia resided in the indifference with which artists chose to express themselves: the medium was not important, what really mattered was the freedom to range from one technique to another.

In 1982 the Italian Transavanguardia maintained a correspondence with the German art milieu, participating in Documenta Kassel 7 alongside the Neuen Wilden (for Italian critics, Nuovi Selvaggi). The latter was a group of young artists from various German cities, united by the physical pleasure of the act of painting in an expressionist style, à la Die Brücke - a style they used to render their perception of reality.

For an international look, one can distinguish other components that can be associated with Transavantgarde. The aforementioned German neoexpressionist strand, with the artists Anselm Kiefer, Jörg Immendorff, Georg Baselitz, Markus Lüpertz, and A. R. Penck. Theirs was a fast-paced, unsettling painting that was distinct from the French situation, with Gérard Garouste, more winking at the Italian Transavanguardia or American pop “graffitism.” Unlike Arte Povera, which long continued to represent Italy in the international art arena, Transavanguardia soon stopped moving as a group.

The substantial lack of homogeneity, both linguistic and poetic, inevitably led the artists to follow autonomous paths, inexorably resulting in the brevity of the artistic phenomenon and the inconsistency of the association.

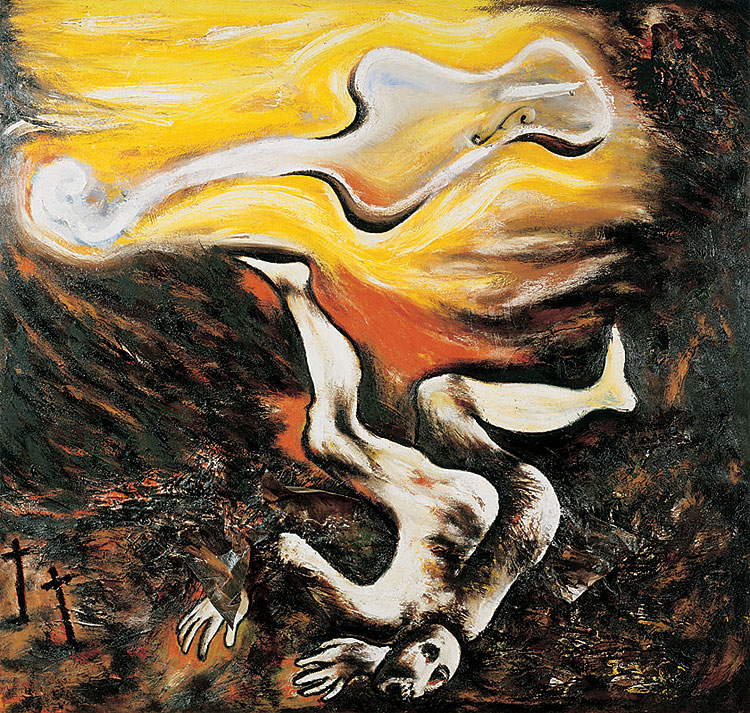

In the process of disbanding the Transavanguardia group, the vicissitudes of some members led them to working autonomy. Enzo Cucchi, in particular, seemed favored toward increasing independent success. The artist drew inspiration from the German figurative tradition, as is evident from Paesaggio barbaro (1983), a painting with dense paint that plays on hazy, acid colors.

In Cucchi’s painting, the faces and figures are deformed and in close connection with certain pictorial solutions of German Expressionism: in Inebriated Music (1982), the figures stretch out in an energetic movement, creating a dark and intense composition. Enzo Cucchi invented his own repertoire of figures, eschewing the rule of decorum. He composed his paintings using numerous techniques, from painting to drawing, from sculpture to artist’s books. Cucchi’s images unsettle but welcome the viewer to immerse himself in the artist’s vision of reality.

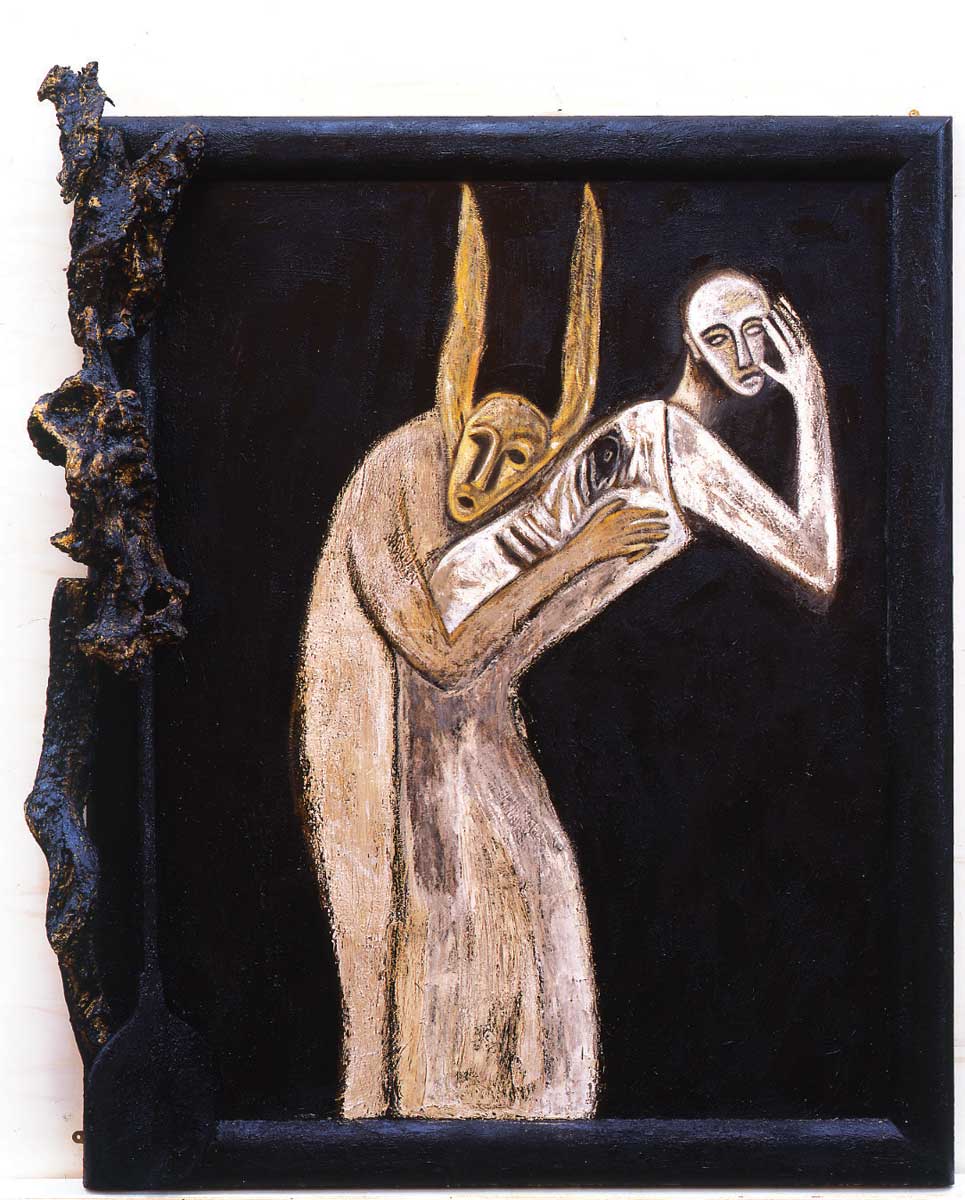

Mimmo Paladino, on the other hand, moved between figurative and abstract, making constant references to the language and semantic area of myth. He wandered through tradition and cultures furthest apart, never really giving in to exoticism: his art is a contamination between symbols and organic forms, between natural forms and anthropomorphic figuration. The artist chased the archaic meaning of the sign by inserting it naturally into his post-modern vision. In Closed Garden, 1982, he exhibited the motif of thehortus conclusus, taking it from the medieval iconographic tradition, where it appeared in both pagan and religious settings. In the work, the symbolic value of a protected place remains intact, and this value is conveyed by virtue of the archaic language pursued by Paladino.

The following year, Paladino produced The Virtue of the Baker in a Carriage, an oil on canvas in which the subjects are affected by a magical, lunar atmosphere. The figures are defined by a few essential strokes, as was the case in primitive cultures and early German Expressionism. These mingle with a fantastic and at the same time monstrous imagery.

In the revival and combination of references to different cultures and moments in art history, the work of Sandro Chia stands out. The artist is characterized by a transgressive, violent pictorial vision. His is a universe made up of anti-heroic subjects and a Michelangelo-like sense of monumentality, often contrasting with the meaning of the composition. In 1982 he made Daredevil Raft, in which he revisited the famous historical painting by French painter Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19). Chia offered an ironic reinterpretation of the nude figures of the classical matrix. The powerful torsos are in stark contrast to the loose brushwork, conducted with a liquid line that downplays the scene. In Sinfonia incompiuta (1980), in the center of the scene is a figure placed with her back turned in the direction of the viewer as she expels a musical score as if it were a physiological instinct.

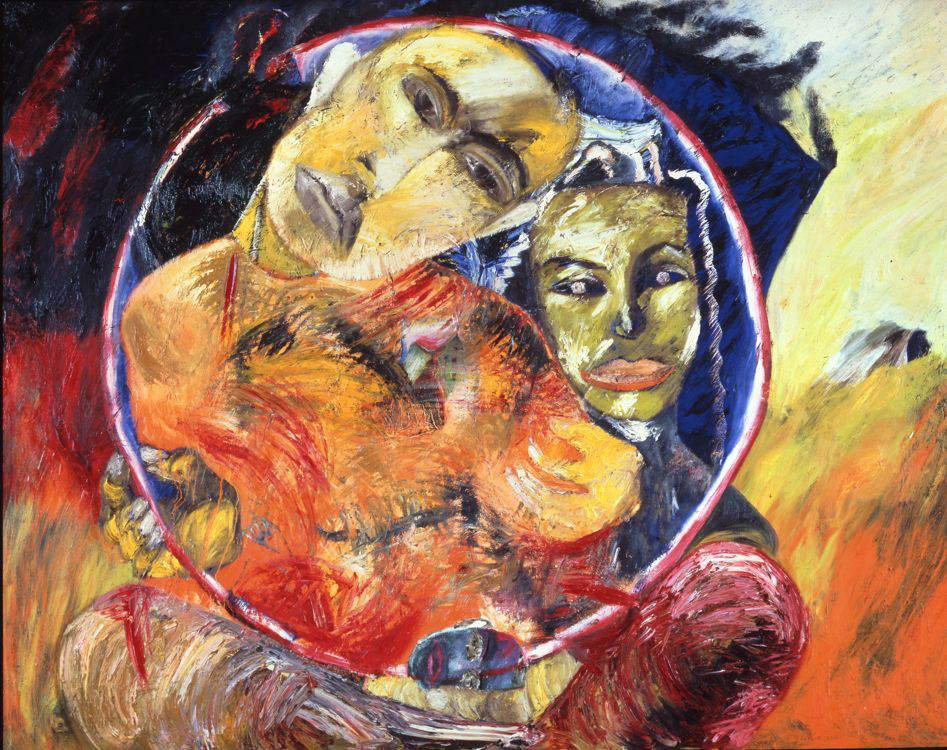

Francesco Clemente (Naples, 1952) deeply investigated his own subjectivity, rendering his own interiority in different aspects in his creations. In his production, the concepts of fragmentary gaze and nomadism typical of the Transavantgarde are understood both as the object of representation and as an investigation of the potential of artistic techniques. In Milarepa’s Circle, a work executed in 1982 and part of a series of twelve canvases, Francesco Clemente represented a subject for which he was inspired by an Eastern tradition. The faces bear his personal suggestions for the figure of a Buddhist monk. The surface of the work is full-bodied, formed by multiple pictorial layers. In the affixing of multiple layers of pictorial matter, one can glimpse an interpretation of the trials the monk had to face during his earthly life as a hermit.

Nicola De Maria was the artist most oriented toward architecture and the exploration of space. He executed large wall paintings, environments in which the viewer is forced to move around losing frontal confrontation with the work. There was in him a great attention to poetry and writing. In 1986 he made Five or Six Broken Spears in Favor of Courage and Virtue, a work in which the artist completely covered a room in the Museum of Contemporary Art in the Castello di Rivoli, Turin, a building with a strong historical connotation. Transcending this detail completely, De Maria painted the walls in different colors to characterize the room in a unique and engaging sense.

|

| Transavantgarde: history, developments, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.