Immediately after the experiences of Masaccio and Beato Angelico and once the patrons had overcome their lack of understanding of Renaissance novelties, we can say, simplifying, that Renaissance painting in Florence took two directions: one that looked to Masaccio’s plasticism and scientific perspective, and the other that instead turned toward Beato Angelico’s sense of colorism (although the situation was more complex and there was no shortage of artists who were participants in both directions imprinted by the two “initiators” of the Renaissance). These two “lines” reflected the orientations of the patrons: those who favored order and harmony (and these were mostly commissions from religious circles, or public works in the city), and those who had appreciated the sumptuousness of the International Gothic and were looking for a style that could continue its brilliance and in some cases its luxury (and in this case they were mostly wealthy private patrons). This was what we can call the second generation of Renaissance painters, most often younger than Masaccio and Beato Angelico, but sometimes even older: they were mostly painters trained in the groove of late Gothic art, who having come into contact with the innovations of the Renaissance wanted to give their art a turn.

This is the case, for example, of Paolo di Dono, nicknamed Paolo Uccello (Florence, 1397 - 1475): he trained together with the late Gothic painter Gherardo Starnina but soon came into contact with artists such as Lorenzo Ghiberti and Masaccio himself. Above a substratum that was still characterized by the fairy-tale atmospheres of the International Gothic, Paolo Uccello, interested in research on perspective (scientific perspective had first found application in painting in Masaccio’s work), devoted himself to perspective almost obsessively. However, the artist rejected perspective artificialis (that of Brunelleschi and Masaccio) to experiment instead thoroughly with perspectiva naturalis (natural perspective), of medieval origin, that is, one that responds not to the laws of geometry but to those of optics. Paolo Uccello is known to have been probably the painter most fascinated by perspective to such an extent that anecdotes about him arose (most famously, the one according to which he neglected his wife to devote himself to his perspective studies), and for creating the most daring perspective compositions of the first half of the fifteenth century that often seem almost to flow into the irrational. This is, for example, the case with the Universal Flood, c. 1447-1448, Florence, Santa Maria Novella, Green Cloister.

Similar to Paolo Uccello’s experience is that of Andrea del Castagno (Castagno, c. 1420 - 1457), who, however, rejected the extreme peaks of Paolo Uccello’s art and directed his research toward an expressionism that he applied to the study of the psychologies of his characters (as in the cycle of the illustrious men, e.g. Farinata degli Uberti, 1449-1451, Florence, Uffizi): a study that derived to Andrea del Castagno from his reading of Donatello ’s art and that influenced not a few artists of the next generation.

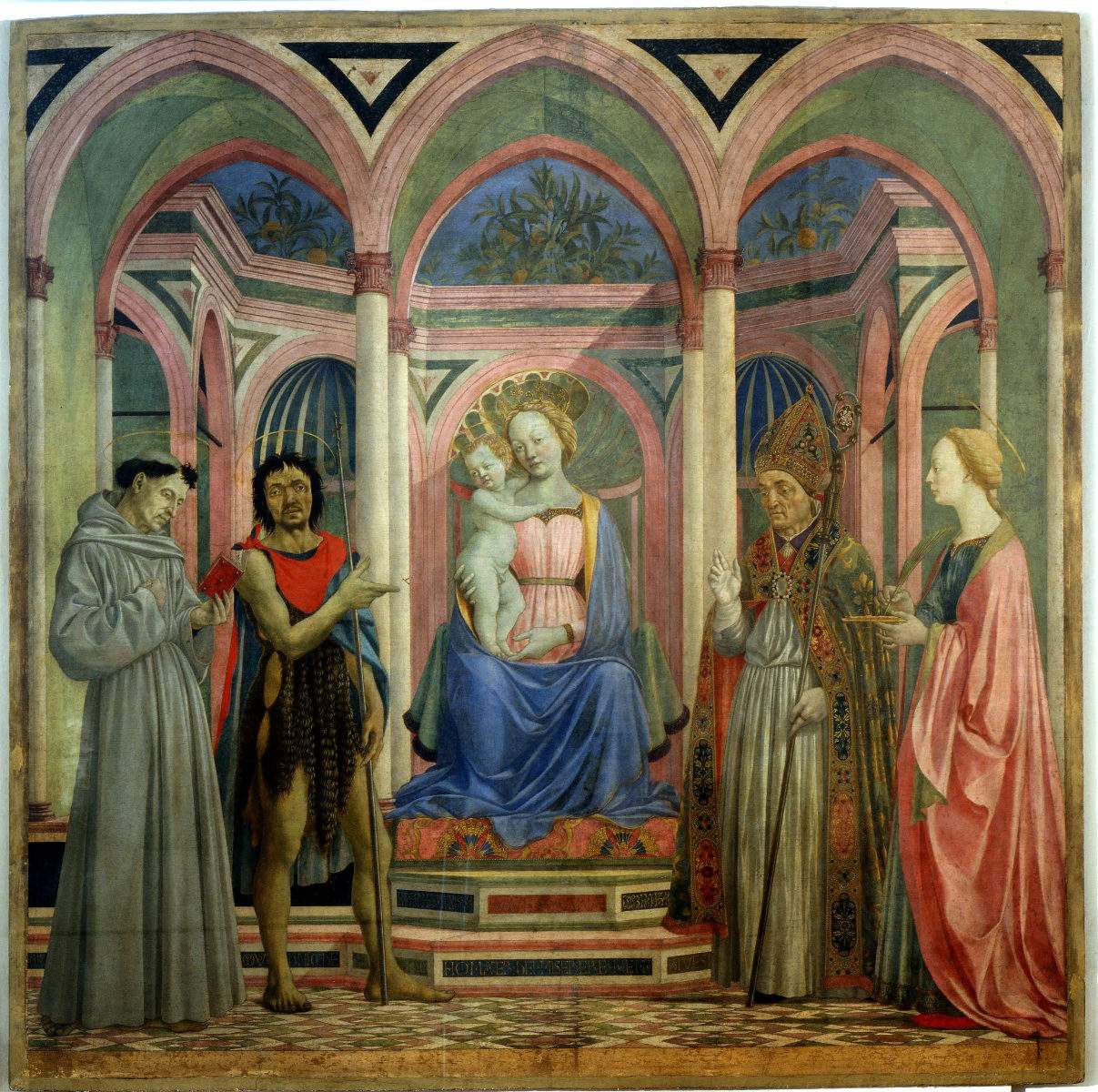

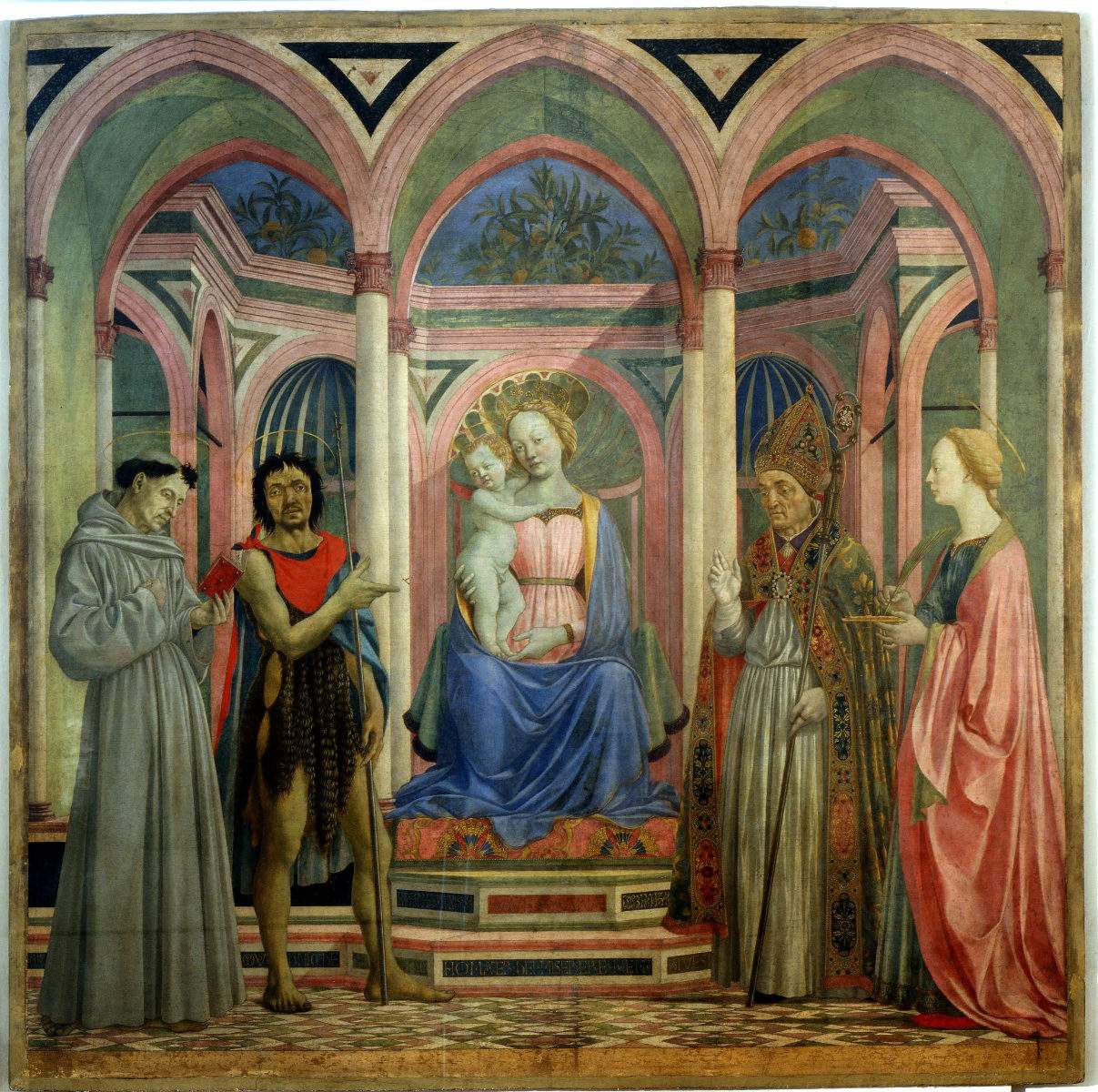

On the opposite front from that of Paolo Uccello and Andrea del Castagno we find instead Domenico Veneziano (Venice, 1410 Florence, 1461): an extremely elegant painter, he proposed an almost aristocratic art that knew how to appeal to a patronage that had not ceased to appreciate late Gothic refinements but that also sought to keep up to date with Renaissance novelties. It is no coincidence that Domenico Veneziano himself was a pupil of Gentile da Fabriano upon his arrival, very young, in Florence, and that from Gentile da Fabriano he took up the great passion for luxury. Domenico Veneziano was also the author of one of the greatest masterpieces of the early Renaissance, the Magnoli Altarpiece (1445, Florence, Uffizi), a panel characterized by brilliant but delicate colors, the rigorous application of scientific perspective, and the persistence of some elements drawn from the lexicon of the International Gothic.

In the midst of these two trends assumed by the second generation of Renaissance painters, stands the figure of Filippo Lippi (Florence, 1406 - Spoleto, 1469), a brother-painter who probably learned to paint almost self-taught, observing Masaccio and Masolino da Panicale at work in the Brancacci Chapel, which was located in the church of the Carmine, that is, the church of the convent into which Filippo Lippi had entered. Filippo Lippi knew how to combine Masaccio’s plasticism with the delicacy of Beato Angelico’s colors, producing now masterpieces with strong, vigorous figures (such as the Trivulzio Madonna, c. 1431, Milan, Castello Sforzesco), now delicate works with an almost intimist flavor (such as the so-called Lippina, c. 1455-1465, Florence, Uffizi). It was, however, his lyricism that was the most important characteristic of his art, a lyricism that was an example for many painters who came after him, above all Sandro Botticelli, who was a pupil of Filippo Lippi.

|

| The second generation of Renaissance painters. Developments, styles, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.