The Secessions: origins, development, and major international exponents

The Secessions were international movements of schism from official art that characterized the Central European art scene in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Arising in reaction to the conservatism of the dominant art institutions of the time, such as the academies of fine arts, associations, and official exhibition circuits, they promoted a renewal of taste and integration between various artistic genres. In several European cities in Germany and Austria, groups of artists formed in the last decade of the nineteenth century that broke with classical academic genres and the preexisting rigid attitude in organizations, giving rise mainly to the Munich Sec ession in 1892, the Vienna Secession in 1897, and the Berlin Secession the following year. These experiences contributed to a new cultural orientation and search for a unifying style of all arts and to the emergence of alternative places and centers to the traditional ones of production, dissemination and promotion.

Strongly connected to the historical, political, and economic conditions of the fin-de-siècle, secessionist artists aimed not only to introduce a new stylistic repertoire but also ignited the debate around modernist art, which involved together the fine arts and the arts, aimed at the production of everyday objects, known as applied art. Art was no longer to be confined and corporate, but to penetrate all fields of everyday life by interpreting the transformations of society, brought about by technological progress and the decisive purchasing power that the bourgeoisie was gaining.

Specific organs of the debate in those years were the magazines founded by the various secessionist groups. In the different national contexts there developed more than a homogeneous stylistic current, a common conscious desire to overcome easel painting and classical sculpture, linked to individual activity and museum display, in favor of an aesthetic and productive group cohesion, starting with architecture.

Origins and development of the Secessions in Munich, Vienna and Berlin

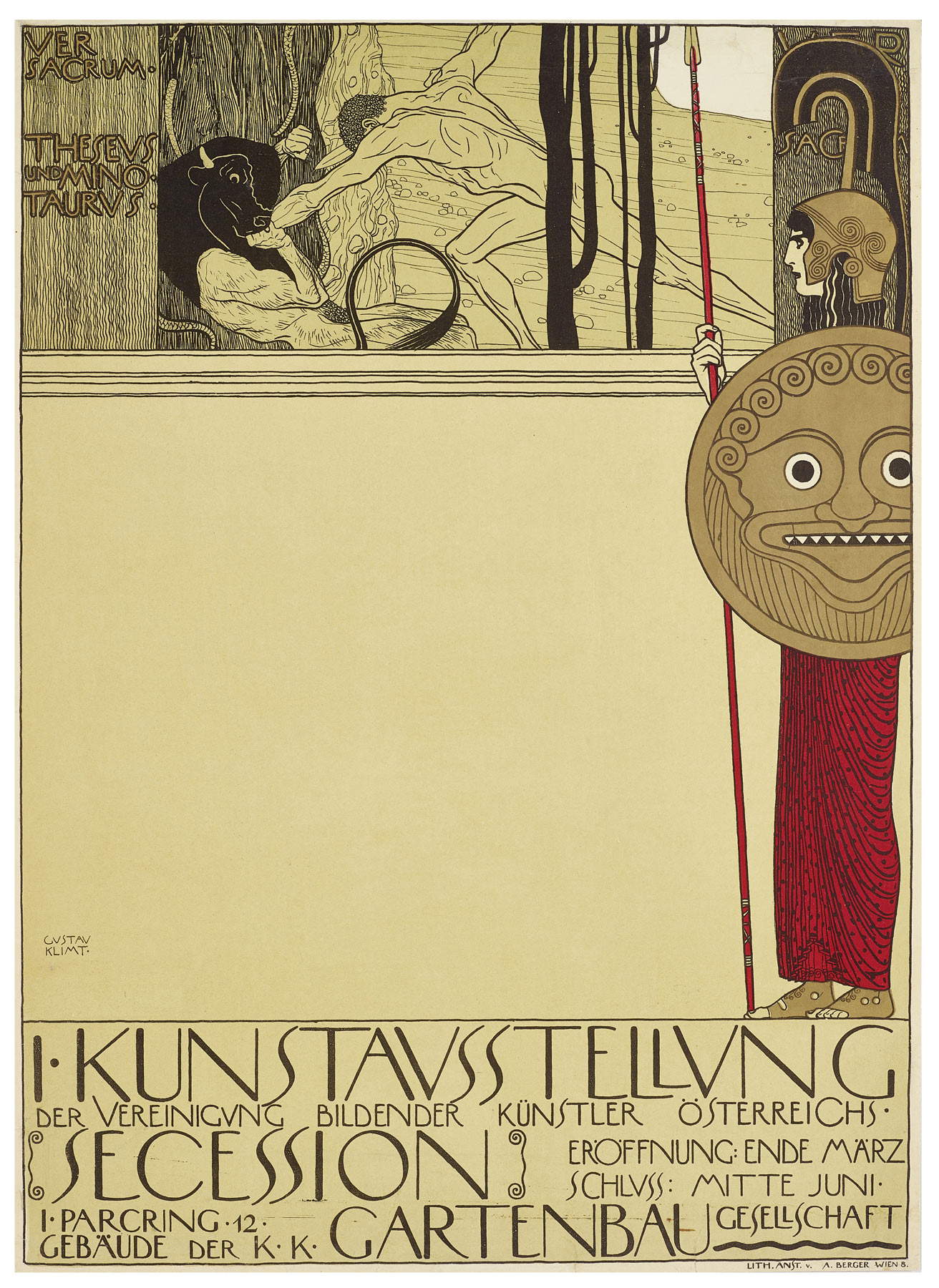

Because of its strong influence at the European level, the best known and most recognized of the secessions is theVienna Secession (Wiener Secession), which was formed in 1897 on the initiative of the painter Gustav Klimt (Baumgarten, 1862 - Vienna, 1918) and the architect, graphic artist and designer Joseph M. Olbrich (Troppau, 1867 - Düsseldorf, 1908), an association of nineteen artists and architects including Josef Hoffmann (Brtnice, 1870 - Vienna, 1956), also like Olbrich a pupil of Otto Wagner, and Koloman Moser (Vienna, 1868 - 1918), who helped establish the highly symbolist and ornamental Art Nouveau style over Austrian artistic conservatism and prevailing commercial taste, in painting as in graphics, architecture as in the decorative arts.

The Viennese Secessionists built their own dedicated venue in the city, the Secession Palace (1897-98), a building that constitutes the first permanent exhibition space dedicated to contemporary art. In parallel with the publication for a five-year period of the official journal "Ver Sacrum" (Sacred Spring), the work of individual artists rehabilitated Austrian art on a global scale.

This formation represents the birth of a forward-looking and internationalist vision of the art system. However, in chronological order, the first secessionist group had formed in Munich in 1892, led by painter and sculptor Franz von Stuck (Tettenweis, 1863 - Munich, 1928) together with art dealer and collector Wilhelm Uhde, with numerous followers. An independent association that countered the conformist politics of the city’s official artists’ association, now considered by many to be backward. The experience of the 96 members who heralded the Munich Secession followed in turn that of the Düsseldorf Artists in 1891, with some fifty members seeking their own exhibition space. The new Munich association immediately operated as a cooperative, formed to secure the economic interests and artistic goals of its members, sparking a real revolution. The exhibition they organized in 1893 was attended by 297 artists, an event that also inaugurated their own purpose-built exhibition building, and counted more than 876 works, including those by Arnold Böcklin of Switzerland along with French artists Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet and the Berliner Max Liebermann, artists who belonged to the nineteenth-century currents of naturalism, Impressionist tendencies and subsequent developments, choices that proved common to those of the Berlin Secessionists.

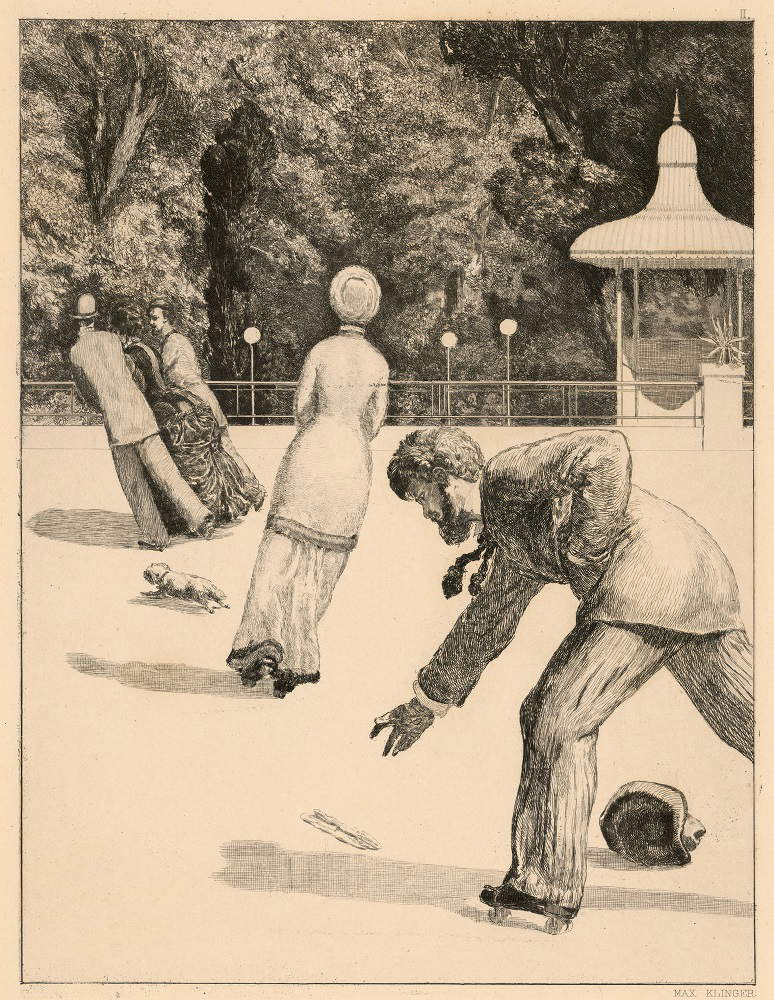

The beginning of artistic discontent in Berlin dates back to 1892 when Gruppe XI was being formed, from the very idea of Max Liebermann (Berlin, 1847 - 1935) and Walter Leistikow (Bromberg, 1856 - Berlin, 1908). An initial split was determined by an exhibition of the Norwegian Edvard Munch (Løten, 1863 - Oslo, 1944) at the Berlin Artists’ Association Exhibition, the official circle of established artists that was to all intents and purposes a guild, where non-Germanic elements were not well regarded and for which the use of color and the emotional charge of Munch’s subjects were not welcome. His works were branded as “ugly and unfinished,” so much so that the exhibition was closed prematurely. The episode for which the painter Munch was forced to withdraw his paintings, referred to as the "Munch Case", paved the way for the voluntary split that later led to the Berlin Secession in 1898, when with the initial promoters 65 artists joined a free association and as in Munich organized themselves to break out of the governmental consolidated art system.

It had happened that year, 1898 that the jury of the Great Berlin Art Exhibition rejected a landscape painting by the painter Leistikow, a key figure in the same group of young artists interested in the modern evolution of art, triggering the final split by its supporters. This Berlin group also gave itself a structure, opposing the corporate condition and demonstrating visual and plastic possibilities even outside the classical and nationalist canons, building its own exhibition halls by architect Hans Grisebach. Affirming the Impressionist trend, they did not fail to present the Post-Impressionists, the Nabis and the Fauves, and, among others, an exhibition in 1902 hosted works by the Swiss Ferdinand Hodler, the Russian Vasily Kandinsky and those of Munch himself, who was present with a large selection of paintings.

The more decisive Vienna Secession in the same years would also offer works by Klimt and Max Klinger, the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, and Hodler in its exhibitions.

Indeed, their goals included establishing contacts with artists internationally and promoting an exchange of ideas, as well as creating a new unified artistic expression that was specifically opposed to the art of the official salons of Vienna. The goals were consciously forward-looking and attempted to break with the past and national traditions, and clearly hoped to inject new outside thinking into a system that for them had become narrow and restrictive.

Concepts and trends of the Secessions

The dominant academic system in art education from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century had hitherto supported the belief that media such as painting and sculpture were superior to crafts such as furniture and object design. The Secessions and the international spread of Art Nouveau sought to overturn that belief by aspiring instead to total works of art, according to the concept so expressed in German Gesamtkunstwerk, which had been popular since 1849 and which describes the combination of different artistic expressions into a single cohesive whole, where each element contributes harmoniously into the whole. The Secessionists operated from exhibition buildings and interiors in which everything from buildings to paintings to objects was envisaged by declining a relative visual vocabulary. The splits that occurred in the various cities and systems expanded into multiple fields of culture affecting not only artists but also institutions. The freedom of expression promoted and proclaimed by the numerous secessionists produced a plurality of styles. The three groups of secessionists also soon divided into internal nuclei and factions and “new” secessions.

As mentioned above, it was the Viennese group that produced some of the most significant works of the period, such as the Secession building that was the site of Olbrich’s exhibitions, which still stands for the movement in its complexity. Rising to anchor itself in the city’s cultural district, it was designed to hold its own against the various surrounding institutional structures, and even from the entrance it presents a clear reference to the revolutionary nature of the Austrians: the inscription"Der Zeit ihr Kunst - der Kunst ihr Freiheit / To every age its art, to art its freedom."

The Palace, on the lines of a design by Klimt who envisioned it as a temple of the arts, ensured that the Secession remained in the public eye both as a permanent architectural monument and as a venue for frequent exhibitions of its direct members and foreign artists. Klimt ’s Beethoven Frieze that is inside, painted for the group’s most famous Secession exhibition in 1902, is a monumental work whose main significance lies in being part of the environment in the sense of totality that the Secessionists sought to create.

Symbols of the power of the Viennese message beyond city limits are the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony (1901-1908) in Germany, also designed by the young architect Olbrich, and the Stoclet Palace in Brussels. Commissioned by a private individual, the Belgian industrialist of the same name, Stoclet, from the Wiener Werckstätte, an association of draughtsmen and craftsmen founded in 1903, it was the product of the collaboration of the Secessionists Hoffmann and Klimt, and in which the latter realized between 1905 and 1909 the Stoclet Frieze, the palace dining room mosaic featuring subjects among the most representative of the artist’s genius in his “golden” or “golden” period, a synthesis of figural and decorative elements. Realizations, these, intended as total, composite and magnificent works of art from which the daily lives of the patrons were to be inspired.

Although the Secessionists were known as a group that attempted to break with artistic traditions, their relationship with the past was more complex than just forward thinking. For example, Klimt, along with many of his fellow painters and graphic artists, cultivated a drive to ’interpret the symbolic nature of mythical and allegoricalfigures and narratives from Greece, Rome, and other ancient civilizations. So too was he inspired by the mosaic culture of Ravenna. With his colors and uncertain boundaries between elements, Klimt initiated the dissolution of the figure that would lead to the spread of abstraction.

The open debate in those years was indicative of the climate in Central Europe, entrusted to the magazines produced by secessionist groups: in addition to the Berlin-based Pan, which began publication in 1895, Jugend appeared in Munich in 1896 and Ver Sacrum appeared in Vienna, which came out from 1898 to 1903. The latter founded and starring again Klimt with Max Kurzweil, influenced the history of editorial graphics and typesetting, also fundamental to the development of Art Nouveau.

|

| The Secessions: origins, development, and major international exponents |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.