Tano Festa, the Italian Pop Art artist: life, works, style

Tano Festa (Rome, 1938 - 1988), an artist, painter and photographer with an intense life, was one of the Italian artists closest to Pop Art. In his youth he became friends with a number of Roman artists who came together in the Scuola di Piazza del Popolo group, including Mario Schifano and Jannis Kounellis. He soon achieved a fair degree of fame that led him to participate in important exhibitions and collaborate with leading galleries in Rome.

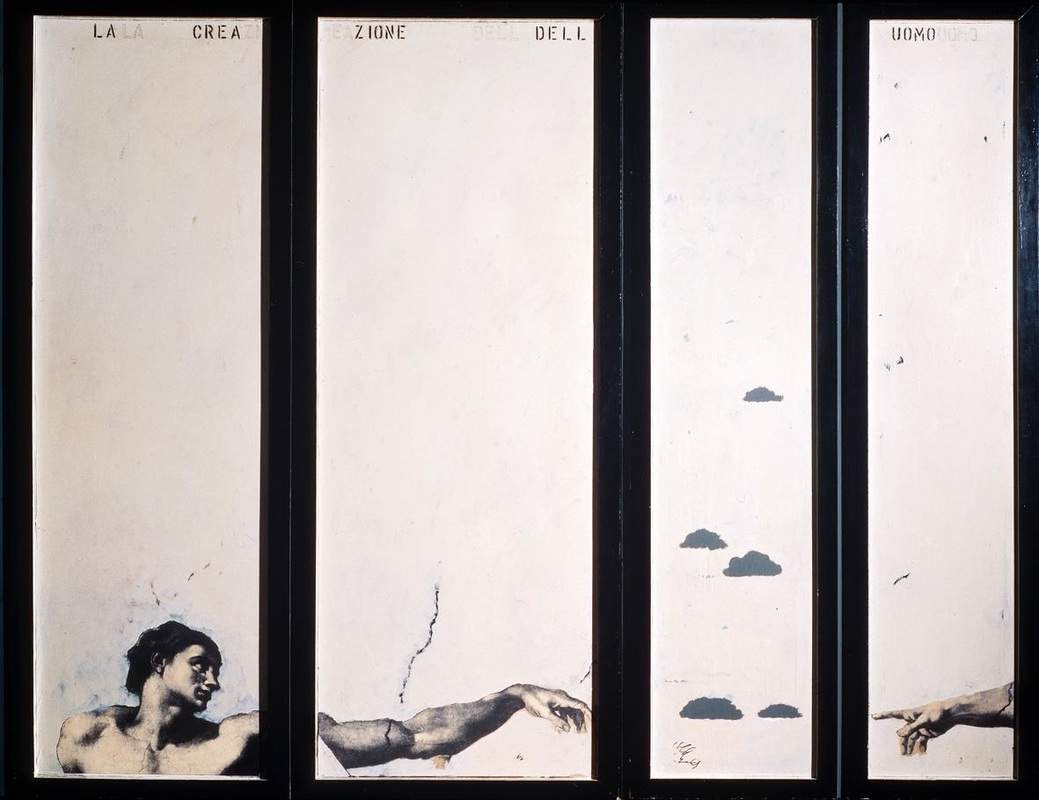

Festa’s production is very varied, but common points can be identified. First, his tendency to produce series of works on the same theme, which Festa carries on even years later. Among the most famous are the series devoted to the ’Adam of the Michelangelo Sistine Chapel, portraits of friends and family members, and Confetti, on bright and colorful backgrounds.

A great admirer, as anticipated, of Pop Art, he has often been defined as an exponent of so-called Italian Pop Art, however Festa was well aware of the difference in context between the United States and Italy, the outcome of which could be, rather, a “popular” Italian art, which takes its cue from the great masterpieces of the past to make them current.

The life of Tano Festa

Tano Festa was born in Rome on November 2, 1938. His mother, Anita Vezzani, came from a family of merchants and was born in the province of Bologna, while his father, Vincenzo Festa, had origins in Palermo and Naples. His father encouraged Festa as a child to paint as a hobby, and the artist himself declared that he “unofficially” began painting at this juncture. He was the brother of another artist, Francesco Lo Savio, so recorded at the registry office, therefore with a surname different from his own. His brother committed suicide at a very young age in Marseilles in 1963, and this episode influenced Festa’s art in later years.

Festa enrolled in 1952 at the Art Institute in Rome, and graduated in 1957 in artistic photography. During these years he hung out with some of his peers who also became renowned artists, such as Mario Schifano, Franco Angeli, and later Jannis Kounellis and Mario Ceroli. Together, this group of important like-minded personalities came to be known as the Scuola di Piazza del Popolo, named after the square where they used to meet, usually in the Caffè Rosati or the La Tartaruga gallery.

Festa first exhibited his work in 1958 at the Painting Exhibition for the Cinecittà Prize, organized by the Italian Communist Party. The following year he established a collaboration with Gian Tomaso Liverani’s La Salita gallery in Rome, one of the most prestigious venues for contemporary art, where he mounted his first solo exhibition in 1961. In the same year he also participated in the XII Premio Lissone and many other exhibition opportunities, consolidating a good level of interest that critics were beginning to show in his work.

The relationship with the critics was fluctuating, as for some periods other artists were preferred to him, leaving Festa somewhat on the sidelines, but in the 1980s some innovations in his pictorial production aroused interest in him again. In 1962 he established a new collaboration with the gallery La Tartaruga, and among its rooms Festa met Giorgio Franchetti, who would become his main collector and supporter. In 1970 he married Emilia Emo Capodilista and moved to his wife’s family home in the province of Padua. Two daughters, Anita and Almorina, were born of the union.

After traveling the world and participating in several major exhibitions both in Italy and abroad, Festa meanwhile battled an illness that took him away in Rome on Jan. 9, 1988, at the age of 49. At his side was journalist Antonella Amendola, whom he had met in 1976. Following his death, an anthological exhibition was held in Rome curated by Achille Bonito Oliva, and another tribute to his figure was paid with another exhibition in the XLV Venice Biennale (1993), entitled Fratelli in that Lo Savio’s works were also exhibited.

Tano Festa’s style and works

Tano Festa’s earliest works, which must have been made between 1956 and 1958, are shown to us through drawings, from which an affinity with Surrealism emerges, while monochrome paintings appear as early as 1960. In these works the canvas is covered with strips of paper, soaked in the same color as the background, so as to give it greater vertical thrust. Festa very often uses the color red, of a tone that is similar to that of blood, in contrast to the vividness found in his friend Mario Schifano. As early as the following year, Festa replaces the paper strips with wooden slats and uses industrial paints, so that the new works show an understanding of the painting as an object. These works are presented in Festa’s first solo exhibition in 1961.

In 1962 real “objects” appear for the first time , i.e., windows, doors, cabinets, and generally common furniture, which are designed by the artist and made to be produced by a carpenter. The peculiarity of these furnishings is that they turn out to be without hinges, handles or locks, thus becoming inaccessible and losing their primary practical function to become art. They include The Red and Black Window and Red Room, in which the color red always remains predominant, and Shutter, which he presented in New York in the “New Realists” exhibition in 1962. The following year, Festa introduced lettering, which he affixed to the inside of the frames of his furniture. Over the years, following the death of his brother Lo Savio, Festa’s proposed objects became melancholy and suggested echoes of metaphysics, investigating the relationship between life and the afterlife.

Between 1962 and 1963 Festa often proposed the theme of the tombstone, and he began to make his first works in which he cited great masterpieces of the past, particularly Michelangelo. In Particular of the Sistine dedicated to my brother Lo Savio (1963) and The Creation of Man (1964), made in two versions, the Creation of Adam, Michelangelo Buonarroti ’s masterpiece frescoed on the vault of the Sistine Chapel, is cited, reinventing it according to different approaches, for example applied on four vertical panels of different sizes that create a sort of screen. Later Festa made other versions in which the face of the Adam is rendered in bright colors reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s work. In the late 1970s, he will use aniline, in deep blue, tracing the outline of the face with a white pencil and inserting spots on the canvas made with acid, which go to interfere with the outline of the protagonist.

The concept behind the quotations from great Italian works lay in wanting to propose an Italian art that was " pop" , in the sense of popular. By the artist’s own admission, U.S. Pop Art proposed consumer objects that were a founding part of local culture, such as Campbell’s soups, brought to the canvas by Warhol in order to take them out of their context and become a cue for artistic reflection, while in Italy he found no such references and could only compare himself with the masters of art history. During a period spent in the United States in 1965, Festa began to develop the technique of hand tracing of projected images, focusing on silhouettes of objects such as paintbrushes, hammers, screwdrivers. He also comes to the reworking of another of Michaelangelo’s works during these years, namely the head of Aurora, part of the complex of the tombs of Giuliano and Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence in the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo. He works on this theme very often, as frequently as the Adam, and uses the technique of projection on canvas, hand tracing and enamel sampling.

Next came the series Gli amici del cuore (1967) and Per il clima felice degli anni Sessanta (1969), in which the names of people close to the artist appear, including artist collectors and gallery owners, such as Schifano, Franchetti, Angeli, Lo Savio and Mimmo Rotella. The images, in black or blue, stand out against a white or blue background, with an essential, geometric design that features some lettering with a stencil or silhouettes of projected images. With the same approach he also made Solitude in the Square (1969), in which he depicts in ways close to pictorial expressionism the silhouette of Admiral Horatio Nelson on the monument in London’s Trafalgar Square.

Between the 1970s and the 1980s Festa would produce several series that share technical details of execution. In fact, in repurposing quotations from past works Festa experiments with a new technique in which the figures are always projected onto the canvas, but are reproduced in a fragmented way going on to lose more and more of their connection with the original work. One example is extracted again from the Sistine Chapel, namely a fragment of the original Tree of Sin placed within perspective frames outlined with chalk, so that all spatial reference is also eliminated. Another proposal concerns names inserted in isolation in lettering in standard type on the canvas, which are often names of nineteenth-century artists complete with dates of birth and death, similar therefore to a tombstone. Among the names mentioned are William Turner, Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir, Vincent van Gogh or Pablo Picasso, with whom several works are created, some of them named Homage to Color.

In the late 1970s, the artist offered two more series, Le Piazze d’Italia and Rebus in which he introduced enamel and aniline on an emulsified canvas. One of his most famous series of this period is certainly Coriandoli, which he elaborates after a period of disappointment from the point of view of critics, who had ignored him and instead returned to him with this proposal. It is a canvas prepared with very vivid acrylic colors, red, green, blue, but also black, on which he then applies real colored confetti. Meanwhile, in the last years of his life Festa often devotes himself to portraits, as in the series The Private Paintings in which he offers enlarged photographs depicting his family members. In the 1980s he uses acrylic color a lot to portray friends and also imaginary figures that are inspired by literature, such as Don Quixote (1987), giving it a dark and hermetic tone. Window to the Sea (1988) is one of Festa’s very last works, visible on the waterfront of Villa Margi between Palermo and Messina and dedicated to the memory of his brother Francesco Lo Savio.

Where to see the works of Tano Festa

The copyright holders of Festa’s works are his two daughters, who have been establishing an Archive of Tano Festa’s works since 2001, with the aim of establishing a catalog raisonné of their father’s entire artistic output. The archive is still under construction, as a public appeal was published on the website tanofesta.it/catalogue for anyone who had a work by Festa in their homes to send documentation of it.

Several works, however, are in Italian museums. Some, for example, are kept at MAMbo in Bologna, in the section “Figurabilità. Painting in Rome in the 1960s,” while Homage to Rothko (1963) is housed at MACRO - Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome.

Also placed in the Vatican Museums is one of the many works dedicated to Michelangelo’s Adam, titled The Dying Militiaman (1979) deliberately just before arriving in the Sistine Chapel.

Often Festa’s works are shown in exhibitions, both solo and group, such as Ricordando Tano Festa. Works 1961-1979, a major anthological exhibition held in 2004 at the Galleria dell’Oca in Rome.

|

| Tano Festa, the Italian Pop Art artist: life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.