Suprematism. History and style of the Russian avant-garde movement.

Suprematism was an avant-garde movement theorized by the Russian painter Kazimir SeverinoviÄ MaleviÄ (Kiev, 1879 - Leningrad, 1935) around 1913, which together with Constructivism constitutes one of the two main Soviet artistic currents of the early twentieth century. Indeed, in Russia, in the years before and after World War I and the 1917 revolution, the artistic avant-gardes were active and incisive movements in arriving at non-figurative positions. The Suprematist movement, joined among others by Olga Rozanova (Melenki, 1886 - Moscow, 1918) and Aleksandr RodÄenko (St. Petersburg, 1891 - Moscow, 1956) to El Lissitzky (PoÄinok, 1890 - Moscow, 1941), was among the first radical developments in abstract art.

The name “Suprematism” was related to MaleviÄ’s belief that art should lead to the “supremacy of pure sensibility in the pictorial arts.” Influenced by avant-garde writers and poets, who interested in questioning the constituent elements of poetic verse and prose were going to break the traditional rules of language, MaleviÄ rejected the idea of art as a copy of nature and rather imagined using its basic geometric forms, squares, triangles, circles, as in Cubist and Futurist painting. In following the path opened by literature, similarly the Suprematists revolutionized visual language.

The Manifesto of Suprematism, conceived in 1915 and published in 1916, presented one of the first organic theorizing on abstractionism, calling on artists to create works of art free from any reference to objective natural phenomena and from realistic imitation of human forms, in favor of geometric rigor “foreign to customary objectivity.”

The Suprematist experience was short-lived, as the newSoviet regime (theSoviet Union came into being in 1922 after the dissolution of the Russian empire) focused on art with a strong social value, especially after Lenin’s death in 1924, thus incompatible with MaleviÄ’s ideas.

History of Suprematism

Abstract, or “nonobjective” or “nonrepresentational,” art was a phenomenon that emerged within the European avant-garde during the second decade of the 20th century. Russia can claim to have been the birthplace of two of the greatest pioneers of abstract art, Vasily Kandinsky (already recognized at the turn of the century as a co-founder of the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter) and MaleviÄ. Suprematism can be seen as the culmination, in Russia, of the interest in geometric forms that from Cubism went on to spread with Futurism, and with “Cubofuturism,” a derivative, distinctly Soviet movement that merged both and to which MaleviÄ initially adhered.

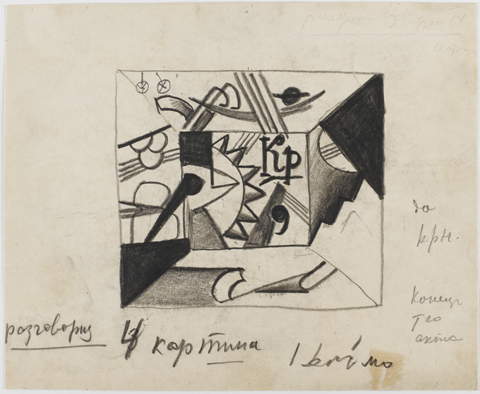

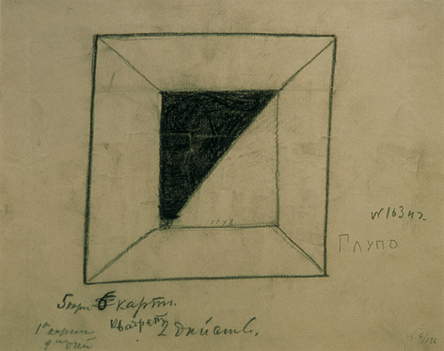

The first expression of the Suprematist experience can be traced back to his designs for Victory over the Sun, a Futurist opera staged in St. Petersburg in December 1913. The stage design MaleviÄ created marked a major break with decorative and illustrative theatrical conventions (usually painted landscapes or interiors), designed to emphasize the parallels between pictorial art, literary text, and music.

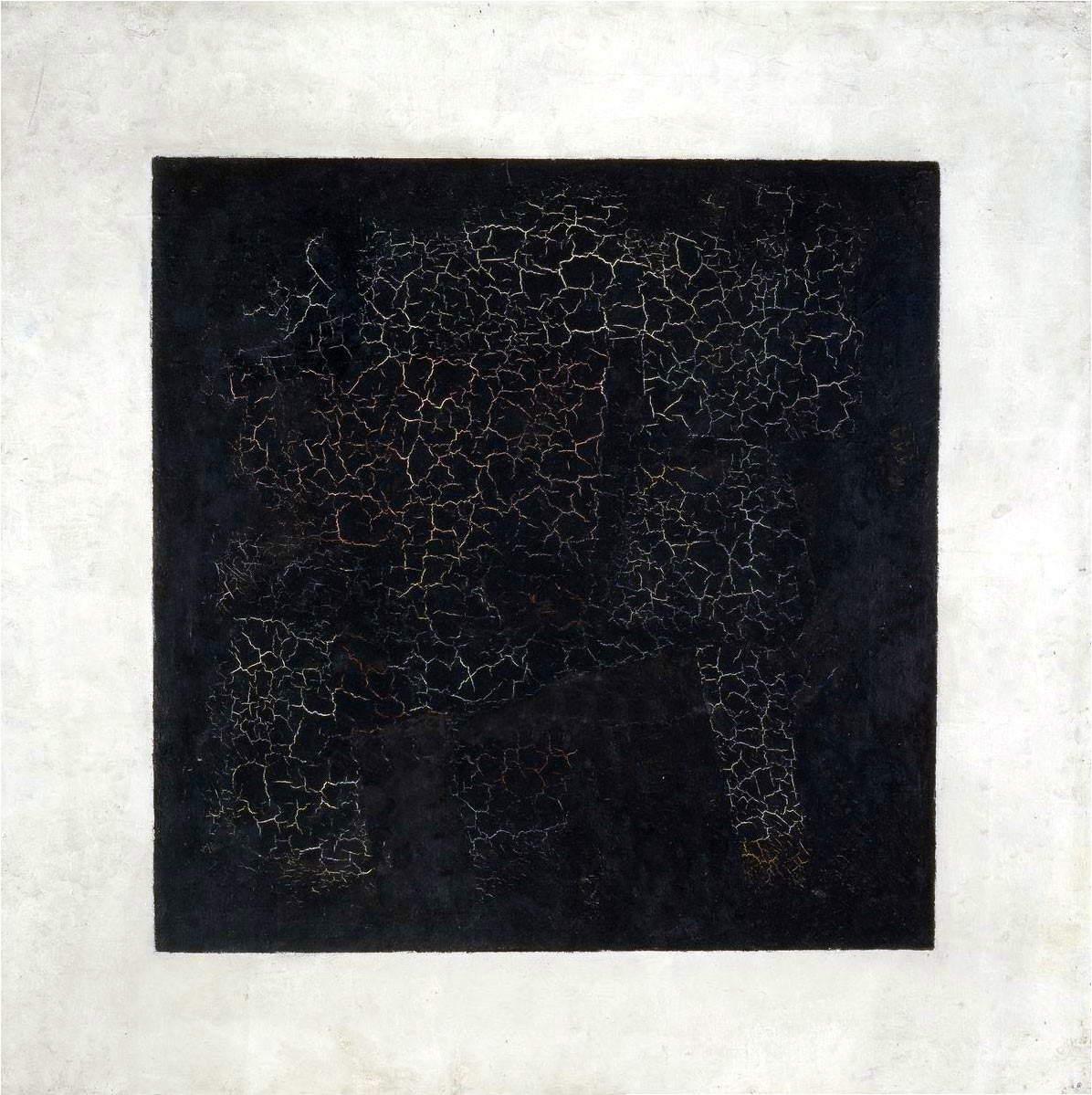

A square, divided diagonally, would appear in the sketches, signifying the invasion of darkness and the arrival of victory over the sun, which would also be the subject of his first work recognized as a Suprematist, a work with the significant title: Black Square on a White Background, in pencil on a neutral field, made later but which the artist backdated to 1913. Of this image, exemplary of his artistic poetics, MaleviÄ proposed over the course of his career at least four versions, with controversial dates. Through the depiction of a geometric form that was neither objective, drawn from nature nor whimsical or inventive, the artist affirmed Suprematism as an art form that would supersede all then-current and earlier art movements. The black square came to be identified with feeling and the white background with “the void beyond this feeling,” he wrote, seeking an “appropriate means of representation, which is always that which gives the greatest possible expression to feeling as such and which ignores the familiar appearance of objects.” In fact, MaleviÄ expressed his Suprematist ideas then only later, in December 1915, at an exhibition called The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10 at the DobyÄina Gallery in St. Petersburg, where he exhibited more than thirty “non-objective” works, with a series of simple geometric forms suspended in the background field.

He was joined by Russian artists Kseniya Boguslavskaya, Ivan Klyun, Mikhail Menkov, Ivan Puni, Lyubov Popova, and Olga Rozanova, among others who, with at the exhibition, announced themselves as the Suprematist group. The variety of shapes, sizes, and angles in their works created in these compositions a sense of depth whereby squares, circles, rectangles, and crosses seemed to float and move in space, completely replacing what up to that time had been only figurative works.

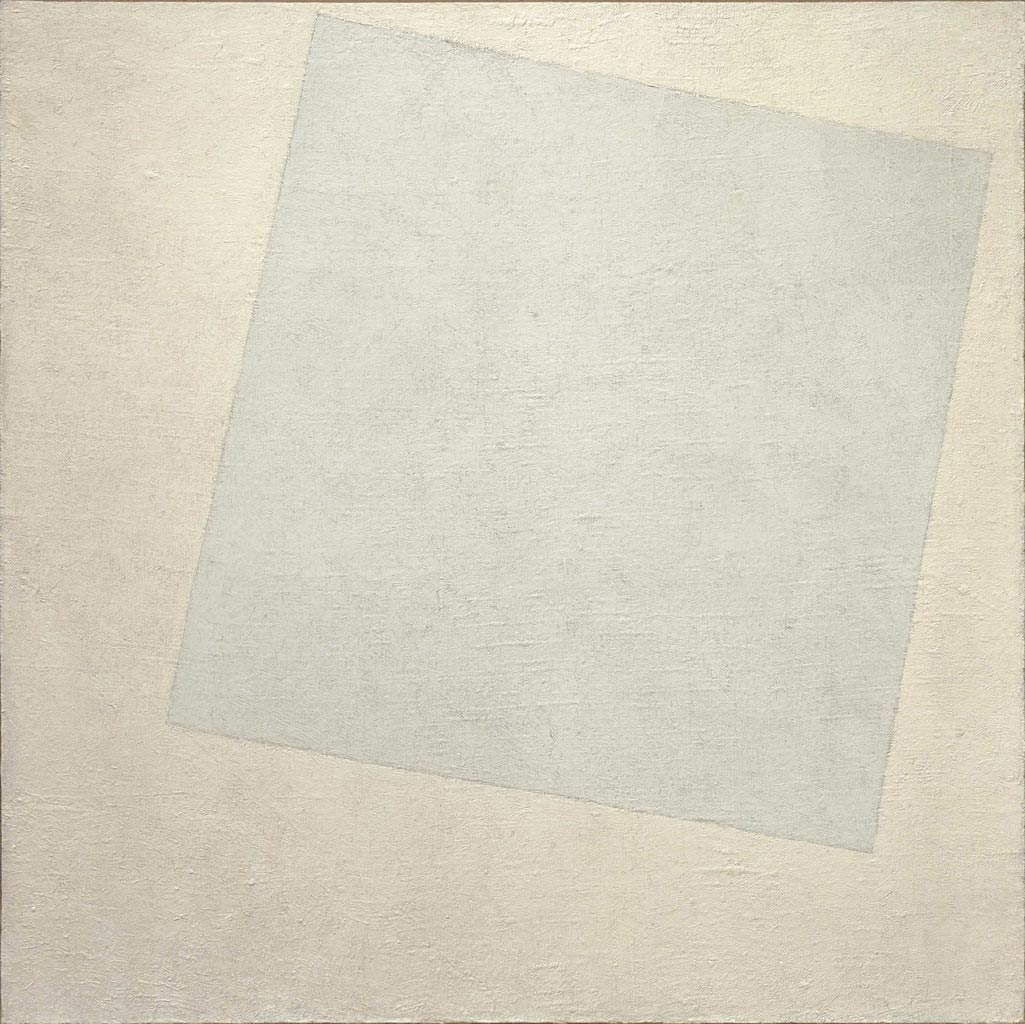

In the winter between 1915 and 1916 MaleviÄ flanked the exhibition with the publication of pamphlets and gave lectures popularizing Suprematism, announcing its intentions in the manifesto entitled From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: the New Realism in Painting. Written with the collaboration of several authors, most notably the poet Vladimir Majakovsky, this text argued that the movement was bringing a new sense of awareness and transcendence to art. While in early productions the artist had limited his palette to a very few essential colors, in 1916-17 he extended his range to include a complexity of forms and spatial relationships that went on to create the illusion of three-dimensionality. His experiments then culminated in the white-on-white paintings of 1917-18, in which barely delineated color and form emerged from the background. MaleviÄ reached, in his quest for the absolute, the extreme limit, the degree zero of painting, as it was understood up to that time, by painting the White Square on a White Ground in 1918. “I have come out of the white,” he wrote, “I have landed in the abyss, here is suprematism. I put all the colors in the sack and tied a knot in it: here is the free white abyss, the infinite, they are before us.”

With the Tenth State Exhibition “Non-Objective Creativity and Suprematism” in Moscow (1919) MaleviÄ announced the end of the movement, later entrusting to a 1920 essay Suprematism, or the World of Nonrepresentation important considerations on his theory of art and his Suprematist poetics. He had thus freed painting from the necessity of depiction. This geometric style, along with other abstract tendencies in Russian art, was transmitted through Kandinsky and El Lissitzky to Germany, particularly to László Moholy-Nagy (Bácsborsód, Bacs-Kiskun, 1895 - Chicago, 1946) a teacher at the Bauhaus, where suprematist ideas circulated successfully in the early 1920s. El Lissitzky, like Aleksandr RodÄenko, later joined the Constructivist movement, which has its aesthetic roots firmly fixed in the Suprematist movement.

The pictorial style of Suprematism

“Not only in the art of Suprematism, but in art in general, the stable, authentic value of a work of art (to whatever school it belongs) consists exclusively in the sensibility expressed,” MaleviÄ wrote. Under his leadership, Suprematism evolved through three overlapping phases, guided by its use of black, color and white alone. Each phase featured paintings that explored a different geometric combination, but each was connected by MaleviÄ’s ideal form, the square.

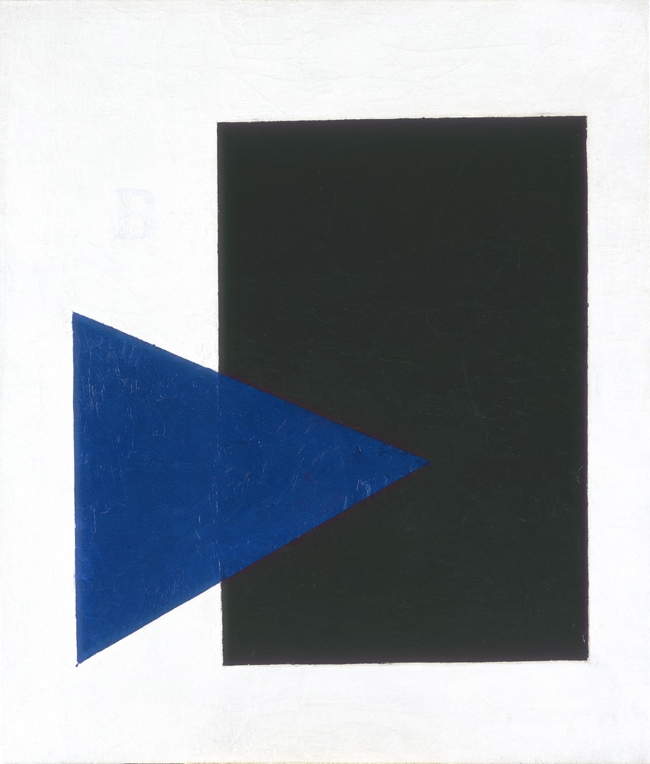

The painter conceptually declared his phases of Suprematism, superimposing this conception on the actual chronology of the paintings’ execution. Indeed, MaleviÄ was in the habit of backdating works by indicating the date when they were conceived, as an idea, rather than when they were actually painted. Beyond that, for the titles he avoided all evocative references, to emphasize their total abstraction and tie them to exclusively pictorial factors, describing only shapes and colors (as with Blue Triangle and Black Rectangle, 1915).

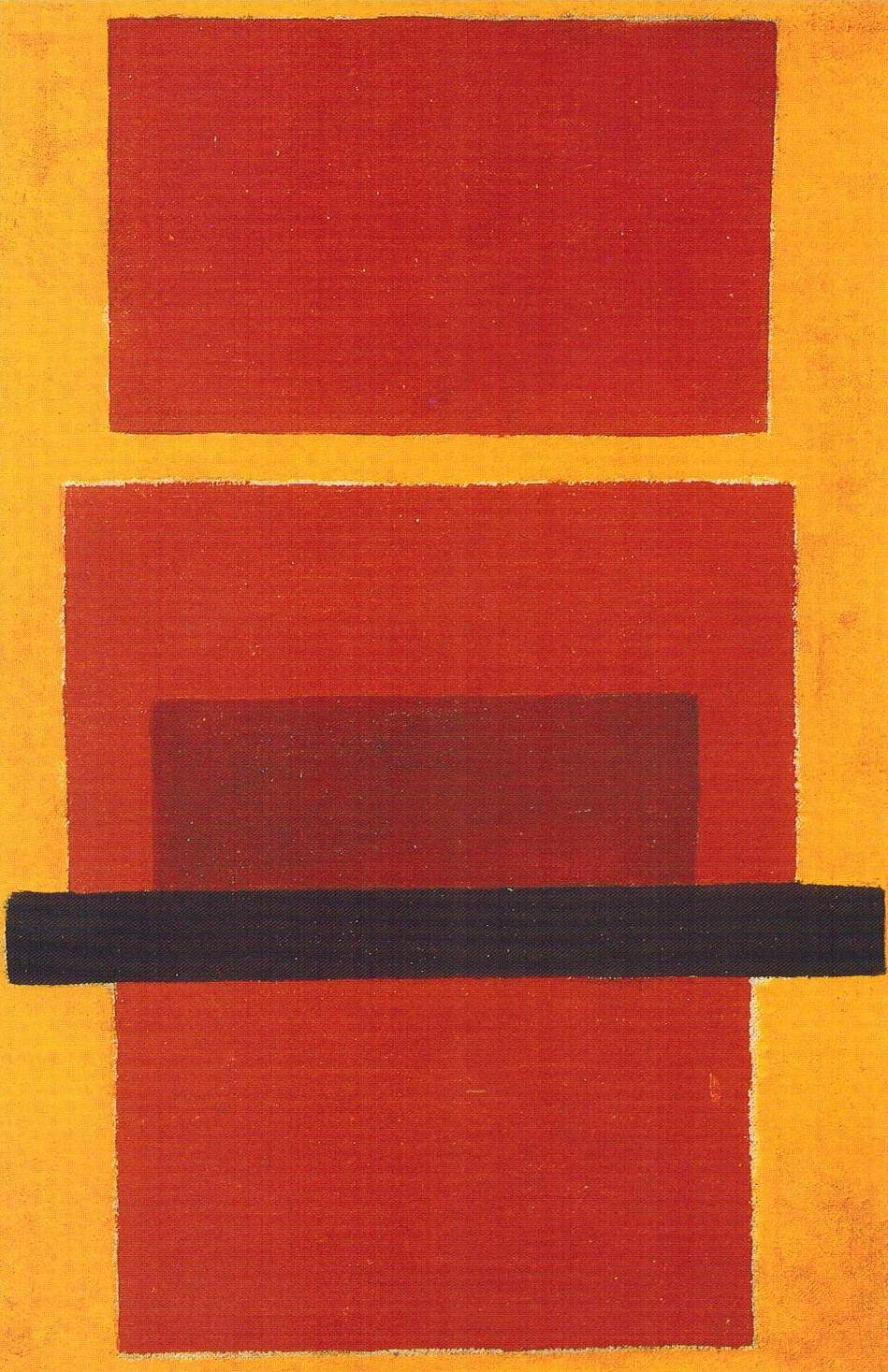

The “black” phase takes its name from most of the paintings in which MaleviÄ presented black forms on a white background, establishing a Suprematist canon: “the first step of pure creation in art,” he claimed, “first there were naive deformities and copies of nature.” In the “color” phase, sometimes referred to as Dynamic Suprematism, MaleviÄ incorporated a limited range of colors. By expanding his palette (albeit moderately), he was able to experiment with relationships of form and color that challenged accepted traditions of painterly harmony and created a greater sense of movement and energy. Olga Rozanova had begun producing colorful geometric collages around 1915, advocating Dynamic Suprematism as a concept. In line with the Suprematist program, she was exploring ways in which simple shapes and colors could provoke emotional or spiritual responses in the viewer. A recognizable example is Color Painting (Non-Objective Composition) of 1917. Toward the end of that 1917, MaleviÄ began to produce paintings in which colored forms dissolved into the white background. A process he described as “dissolution.”

In the definitively “white” phase, the painting White on White, indeed, of 1918 (there were four versions of it with subtle variations) was the pinnacle of the movement. Renouncing form almost completely, the work announced itself as seemingly nothing more than an idea or concept (hence the use of the term “dissolution”). The painting was exhibited at the Tenth State Exhibition “Non-Objective Creativity and Suprematism” in 1919. MaleviÄ wrote, “even the white color is still white, and in order to show the forms in it, it must be created so that the form can be read, so that the sign can be received. And so there must be a difference between them but only in the pure white form.” MaleviÄ had come to the conclusion that white embodied the entire spectrum of colors, and was the only one that offered his viewer the possibility of contemplating the existence of the divine.

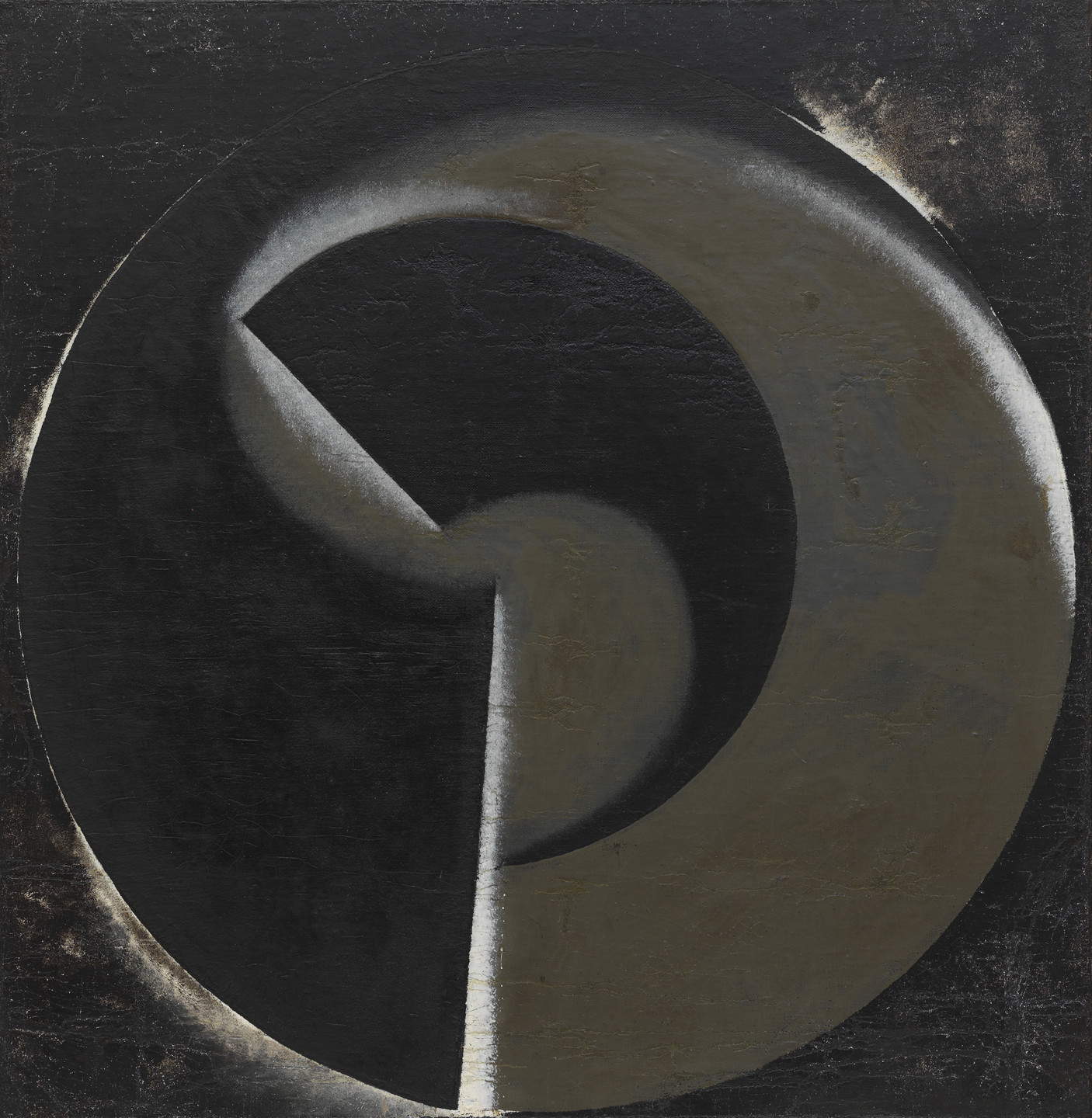

Also exhibited at the Tenth Moscow Exhibition was, among others, Aleksadr RodÄenko’s Non-Objective Painting No. 80 (Black on Black), placed directly opposite MaleviÄ’s White on White. In addition to the similarities between the titles, parallels were intercepted between the two works: they had roughly the same size, texture and tone (with combinations of matte and glossy colors), where, however, the thick black-on-black curves, which took the overall shape of a circle, served as a counterpart to the white square on a white background. RodÄenko who had approached Suprematism with a painting the year before in 1918, and still continued to use black in a variety of textures and finishes, to in turn found a painting of physical properties, bringing attention to the material quality of the surface.

These years saw the birth of a new chromatic significance in painting as in graphic design, of which the works of El Lissitzky, who was one of MaleviÄ’s students at the Revolutionary People’s Art School in Vitebsk, founded by Marc Chagall and later directed by MaleviÄ, are exemplary. Lissitzky’s 1919 lithograph Beat the Whites with a Red Wedge is considered one of the most iconic of all Russian avant-garde works and, in its preference for basic geometric shapes and colors, is indicative of the transition from Suprematism to Constructivism.

|

| Suprematism. History and style of the Russian avant-garde movement. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.