Spatialism, origins, theory, styles

The term Spatialism is intended to refer to an artistic trend that was officially born in Argentina but defined itself in Italy in the 1950s. The movement’s birth is inextricably linked to the name of Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968): born to an Italian family, he studied in Milan, at the Brera Academy, but returned often to Argentina, where he worked as an artist and teacher. In Buenos Aires, in 1946, the artist began to set the foundations of Spatialist poetics. Returning to Italy the following year, he was able to continue to work in this direction thanks to the cultural scenario he found there; although it was a post-war moment, he did not encounter a poor situation, but was able to experience a very intense and creative season, which brought Italy on a par with other European countries.

In the 1950s in Italy, the artistic outcomes were essentially Abstraction and Informal: artists often went through various phases, inevitably passing from Neo-Cubist and Picasso-like figuration. In this sense, Lucio Fontana testifies to a number of Italian sources that had nothing to do with Surrealism or Cubism. In fact, the artist was barely touched by the “Picassianism” of those years, turning rather to consider the progressive impulse pertinent to the poetics of Futurism. The definition of Spatialism was thus structured by a series of debates that took place in Milan, at the Naviglio Gallery. They were exchanges that led to the drafting of manifestos that Fontana signed beginning in 1947, with the support of other intellectuals including critic Giorgio Kaisserlian, philosopher Benjamino Joppolo, and writer Milena Milani.

The term refers to the new “space age,” with developments in the field of technology and all those innovations that made it possible to disintegrate the limits created by matter and led toward the exploration of communication via the airwaves. Devices such as radio and television became models of inspiration, as they were able to break down material three-dimensionality to open a window to the “fourth dimension.” In this sense, the spatial movement fully returned the face of its time, constituting an account of the society of those years that was discovering the possibilities allowed by the new media. Given the new availability of resources, new attitudes and new ways of understanding and practicing art were inevitable.

The spatial movement was joined by artists such asRoberto Crippa (Monza, 1921 - Bresso, 1972),Enrico Donati (Milan, 1909 - Manhattan, 2008),Gianni Dova (Rome, 1925 - Pisa, 1991), Tancredi Parmeggiani (Feltre, 1927 - Rome, 1964), and Milena Milani (Savona, 1917 - 2013). Artists such as Giuseppe Capogrossi (Rome, 1900 - Rome, 1972), Ettore Sottsass (Innsbruck, 1917 - Milan, 2007), Alberto Burri (Città di Castello, 1915 - Nice, 1995), Enrico Castellani (Castelmassa, 1930 - Celleno, 2017), and Agostino Bonalumi (Vimercate, 1935 - Desio, 2013) also had some spatialist experience.

![Lucio Fontana, Black Light Spatial Environment (1948 [2017]; reconstructed installation for Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan). Photo: Agostino Osio / Lucio Fontana Foundation Lucio Fontana, Black Light Spatial Environment (1948 [2017]; reconstructed installation for Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan). Photo: Agostino Osio / Lucio Fontana Foundation](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/fn/lucio-fontana-ambiente-spaziale-a-luce-nera.jpg)

Birth and development of Spatialism: the manifestos

“Art is in a latent period. There is a force that man cannot manifest. We express it in literal form in this manifesto. Therefore we ask all men of science in the world, who know that art is a vital necessity of the species, that they direct a part of their investigations toward the discovery of this luminous and malleable substance and of instruments that produce sounds that enable the development of tetradimensional art.” Thus opens Manifiesto Blanco, a text in which the Spatialist movement found its first foundations. The manifesto, published in the form of a leaflet, grew out of Lucio Fontana ’s (who returned to Argentina during the years of World War II) collaboration with young artists and intellectuals from the Academy of Altamíra, from their exchange of new research ideas. Published in Buenos Aires in 1946, it was drafted by Bernardo Arias, Horacio Cazenueve and Marcos Fridman, and was also signed by Pablo Arias, Rodolfo Burgos, Enrique Benito, César Bernal, Luis Coli, Alfredo Hansen and Jorge (Amelio) Rocamonte.

The text echoes an energetic force already characteristic of the Futurist manifestos: the signatories did not include Fontana, who was founder and teacher of the Academy at the time and held a position of official recognition. The artists urged the “overcoming of painting, sculpture, poetry and music, to arrive at an art based on the unity of time and space.” It was a theoretical formulation that denounced the urgency that art had to renew itself, the need for a cultural response to the new stimuli that every area of life was experiencing thanks to technological and scientific achievements. “The development of three-dimensional art” was one of the priority goals in Spatialist poetics, as was the desire for “trespassing” to discover the potential of artistic expression beyond the imposed threshold of matter.

The search for the fourth dimension, was encouraged in every sphere of art: “A change in essence and form is demanded. Overcoming painting, sculpture, poetry and music is called for. A greater art is required in accordance with the demands of the new spirit.” With a view to pursuing the idea of an art that was totalizing, the old groove already beaten by the historical Avant-gardes was taken.

When Lucio Fontana returned to Milan in 1947, he embarked on an unprecedented quest, completely aimed at the spatial concept. Gallery owners Renato and Carlo Cardazzo organized a series of public meetings at the Galleria del Naviglio to interpret and explore this research. It was from here that Spatialism found its first real definition, announced in the First Spatial Manifesto that bore the signatures of Fontana and also of critic Giorgio Kaisserlian, philosopher Benjamino Joppolo and writer Milena Milani.

The research undertaken by Lucio Fontana started from the consideration and ideas of the artist Umberto Boccioni (Reggio Calabria, 1882 - Verone, 1916). According to the artist, Boccioni was the only one who initiated his own expressive research toward breaking down the two-dimensional barrier, guiding his art toward physical expansion and figurative dynamism. Fontana appreciated a similar "conquest of space,“ which he believed was also characteristic of the development of Baroque art, with the theatricality of its bizarre forms, ”The Baroque has directed us in this direction, [...] the figures seem to abandon the plane and continue in space the movements represented.[...] the physics of that epoch reveals for the first time the nature of dynamics, it is determined that motion is a condition immanent to matter as the principle of the understanding of the universe" (from the Technical Manifesto of Spatialism, see below).

Investigations of this sort helped break out of traditional patterns, leading to the conception of immateriality that flowed into Spatialism: in the First Spatial Manifesto, in fact, the status of the work of art is largely questioned. “Art is eternal, but it cannot be immortal. [...] It will remain eternal as gesture, but it will die as matter.” Importance was given to gesture as a manifestation of thought: these are the statements that underlie experiments such as the Spatial Environments or the Neon Spatial Concept that Fontana made in the 1950s.

A second draft of the Manifesto took place in March 1948: the need to loosen ties with the art of the past was reiterated, coming out of its “glass bell,” proceeding to the use of new technical means. Two years later, the Proposal for a Regulation (the Third Spatial Manifesto) was circulated, organized into nine points, one of which enunciates that “The Spatial Artist no longer imposes a figurative theme on the viewer, but puts him in a position to create it for himself, through his imagination and the emotions he receives.” Like many other art movements of the second half of the twentieth century, Spatialism breaks down the contemplative passivity of the visitor who is rather called to the performance of an active role, to interaction with the new spatial concepts.

In 1951, the Technical Manifesto of Spatialism recovered the theme of the need for art to evolve in tune with new technological and scientific discoveries. “The conditions of life and society and of each individual are being transformed. [...] The discoveries of science gravitate to every organization of life. [...] The application of these discoveries in all forms of life creates a substantial transformation of thought. The painted cardboard, the upright stone no longer make sense; the plastics consisted of ideal representations of known forms and images to which they ideally attributed reality. The materialism established in all consciousnesses demands an art far removed from the representation that today would constitute a farce.”

This was followed by the publication of the Fourth Spatial Manif esto in 1951, which drew a balance, and in May 1952 the Manifesto of Spatial Movement for Television saw the light of day, coinciding with the experiments Fontana conducted for RAI, using canvas and perforated papers to project moving light images. The paper recognized television as “a medium [...] integrative of our concepts,” that is, an extender and multiplier of visual forms and experiences.

As the various manifestos had to describe it, Spatialism represented the need to create an art of the future, one that lived in its time, told its science, and was transmissible in space. Theattraction to the cosmos was the impetus that Fontana and other artists felt for directing their research toward a new dimension. The results of these studies were first gathered in 1952, when the Galleria il Naviglio in Milan presented the first spatial group show: Milena Milani, Gian Carozzi, Roberto Crippa, Beniamino Joppolo, Lucio Fontana, Cesare Peverelli, Henry Mitchell and Vander Spuis. Here the Spatialists illustrated how the concept, the content of the work could be conveyed by any material medium.

Works by Lucio Fontana and other trends

From the early 1930s, Lucio Fontana was committed to overcoming the conception of sculpture as a static object closed within limits with respect to the space that accommodates it. The artist wanted to break relations with the values of classical statuary in order to reconnect with Boccioni’s dynamism, the Futurist lesson. Signorina seduta of 1934 is a work in which the plastic element was conceived in relation to the surrounding space. Figuration here became a pretext for investigating the space around, hence the use of gold in the maiden’s hair, which increases contrast and modulates light. The black robe also catches the light because of the roughness of its material, which is vibrant and charged with dynamism. In this bronze, Fontana more decisively implemented that synthesis between sculpture and painting already tentatively attempted by the Informal movement.

In Fontana’s research, the conception of the work of art changed: it now went from the object to the environment. It was 1949 when Fontana set up Ambiente spaziale a luce nera (Spatial Environment in Black Light): in a room of the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan, Fontana responded to the need for a “new vision of art” by placing a papier-mâché sculpture covered with fluorescent paint and hung from the ceiling of a room completely painted black. An ultraviolet-emitting light (Wood’s lamp, invented in 1935) was the only light source. The impression was that of floating in an infinite, enveloping dimension. With this installation, Fontana entered the heart of spatialist research, aimed at the trespassing of physical limits. It was the first Italian environmental work, conceived as a space where “each viewer reacted with his or her state of mind of the moment.” TheSpatial Environment of the Naviglio, in fact, was an installation created to act energetically on the sensory and emotional faculties of the public.

From this first truly “spatial” work, Fontana began to conceive of light as plastic matter. Later, the large neon Spatial Concept was inserted in this direction. The work was created in collaboration with architect Luciano Baldessari for the grand staircase of the 1951 Milan Triennale, the same year in which the Manifesto Tecnico was published. If in theSpatial Environment of 1949 Fontana had used black light to modulate the perception of matter in space, in 1951 the artist used light to draw in space; he created an “arabesque” by bending one hundred meters of neon tubes.

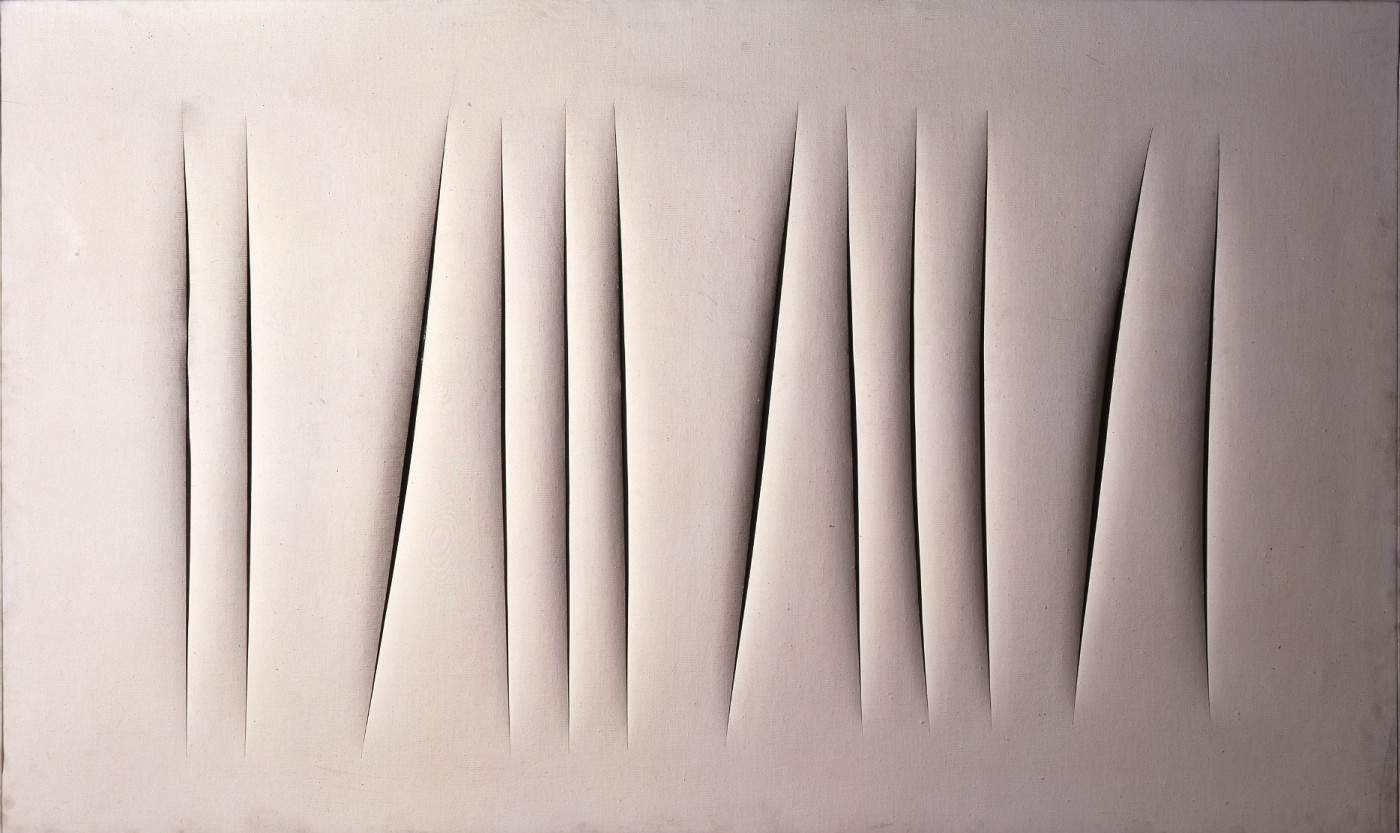

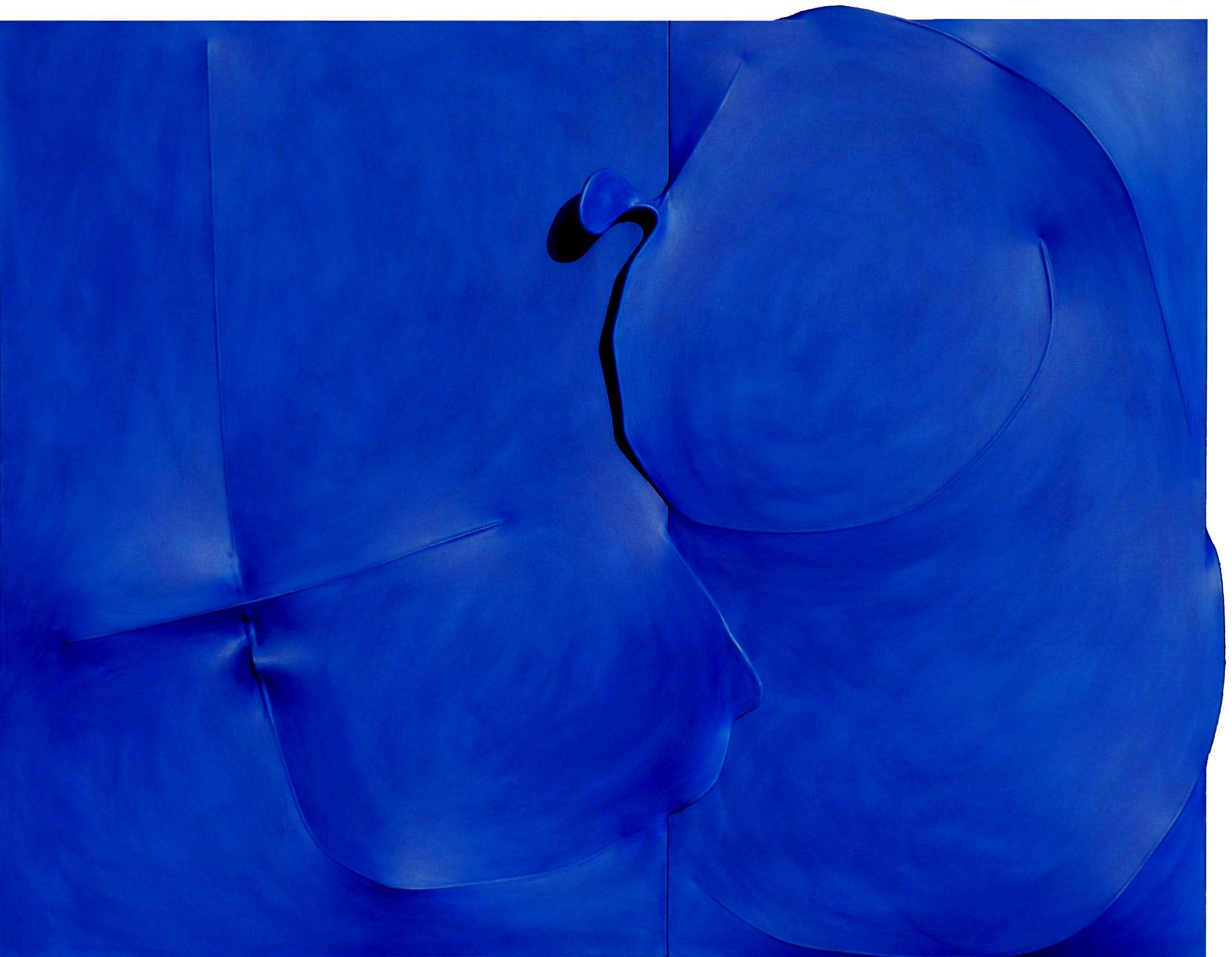

Fontana’s research took place mainly in the spatial void: parallel to the environment, he conceived form and spatial research on canvas as well, since the concept can be applied anywhere. In 1949 he began the Spatial Concepts series, “The discovery of the cosmos is a new dimension, it is infinity: then I pierce this canvas that was the basis of all the arts and I have created an infinite dimension.” So Fontana had this to say to Carla Lonzi in a famous interview. The “hole” is not a destructive gesture but an action that brings the concept of space into the work, it is the opening beyond the limit. The mental operation that gives rise to the gesture of opening matter to spatial conception is what led Fontana to the series to which his name will remain permanently linked: the Cuts. Seemingly simple impulsive gestures, they are actually the result of sharp and very thoughtful incisions (read more about how Fontana’sCuts were born here ). The surfaces of the canvases are always monochrome, in strong pure colors such as red and blue, often painted with an application of water paint to impart gloss and immateriality. By carving the canvas, Fontana created a cosmic and compositional balance, erasing the traditional physicality to which the material is bound. The first cut was made by the artist in 1958: this was the start of the series for which Fontana claimed to have succeeded “in giving the viewer of the painting an impression of spatial calm, of cosmic rigor, of the serenity of the infinite.” Whether they were one or several cuts juxtaposed, each remains a placid, unique and unrepeatable gesture, an opening to the infinite, a dimension suspended between the material world and conceptual space. The indeterminacy was appropriately suggested by the subtitle Waiting.

Fontana’s work also found space in the field of ceramics: Battaglia, 1947, demonstrates how he made works with a figurative theme, however, always giving much expressive value to the material, which twists, clumps and returns effects of great dynamism. In Albisola, between 1959 and 1960, he made Concetto spaziale. Nature, where irregular spheres in terracotta or even bronze were slabbed, drilled, carved; nevertheless, they retained the energy of a primal matter.

None of the spatial artists who orbited Fontana ever approached the complexity and articulation of Cuts ’ canvases or his installations. Spatialism, therefore, remained anchored in the figure of the Italian-Argentine artist, although it meandered among the artistic languages of different personalities; Spatialist nuances also appeared in the activity of artists such as Alberto Burri, Giuseppe Capogrossi, and Ettore Sottsass. In fact, according to Spatialism, the concept could be rendered in any medium.

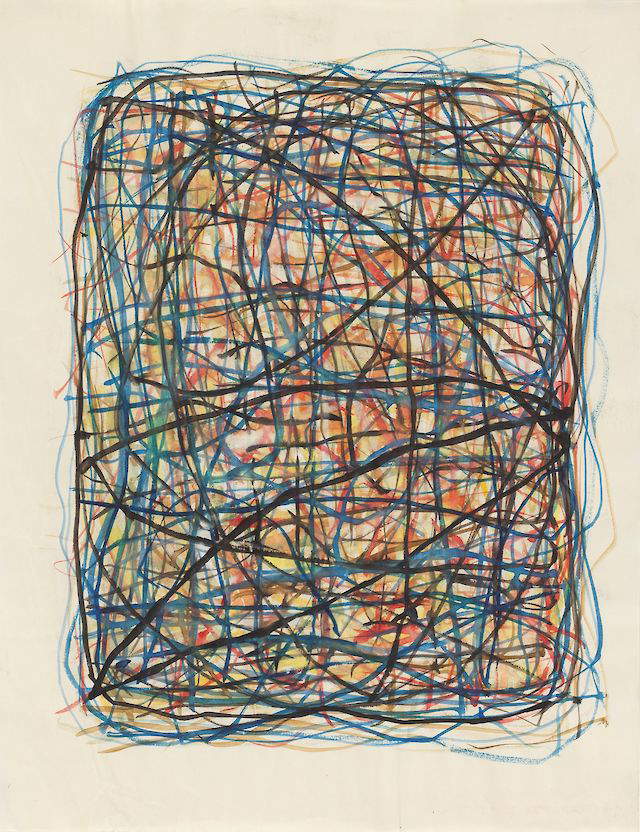

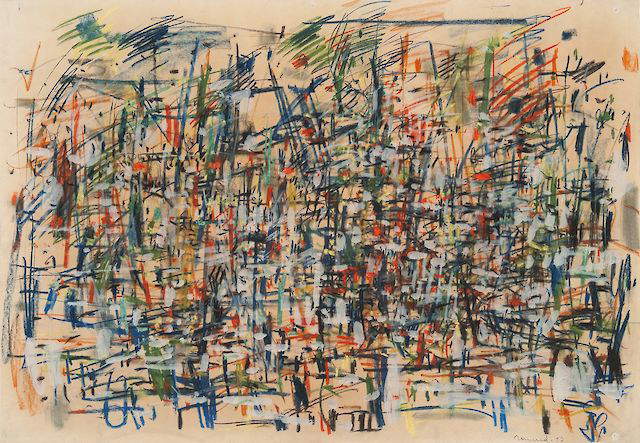

Milena Milani was one of the first signatories of the 1947 Manifesto: with her, a Ligurian writer and journalist, the word understood as a conceptual sign found hospitality on decidedly innovative majolica, ceramics and canvases. Tancredi Parmeggiani, a friend of Carlo Cardazzo and Peggy Guggenheim (who bought his works and promoted them in the United States) subscribed to the 1952 Manifesto, and exhibited several times at the Galleria del Cavallino in Venice and the Galleria il Naviglio in Milan. Tancredi understood Spatialism yes in a strongly pictorial declination, but working much on the side of sign, recalling that of the American sources of painters Mark Tobey and Jackson Pollock. This is evidenced by some Untitled works purchased by Peggy Guggenheim herself and kept in Venice.

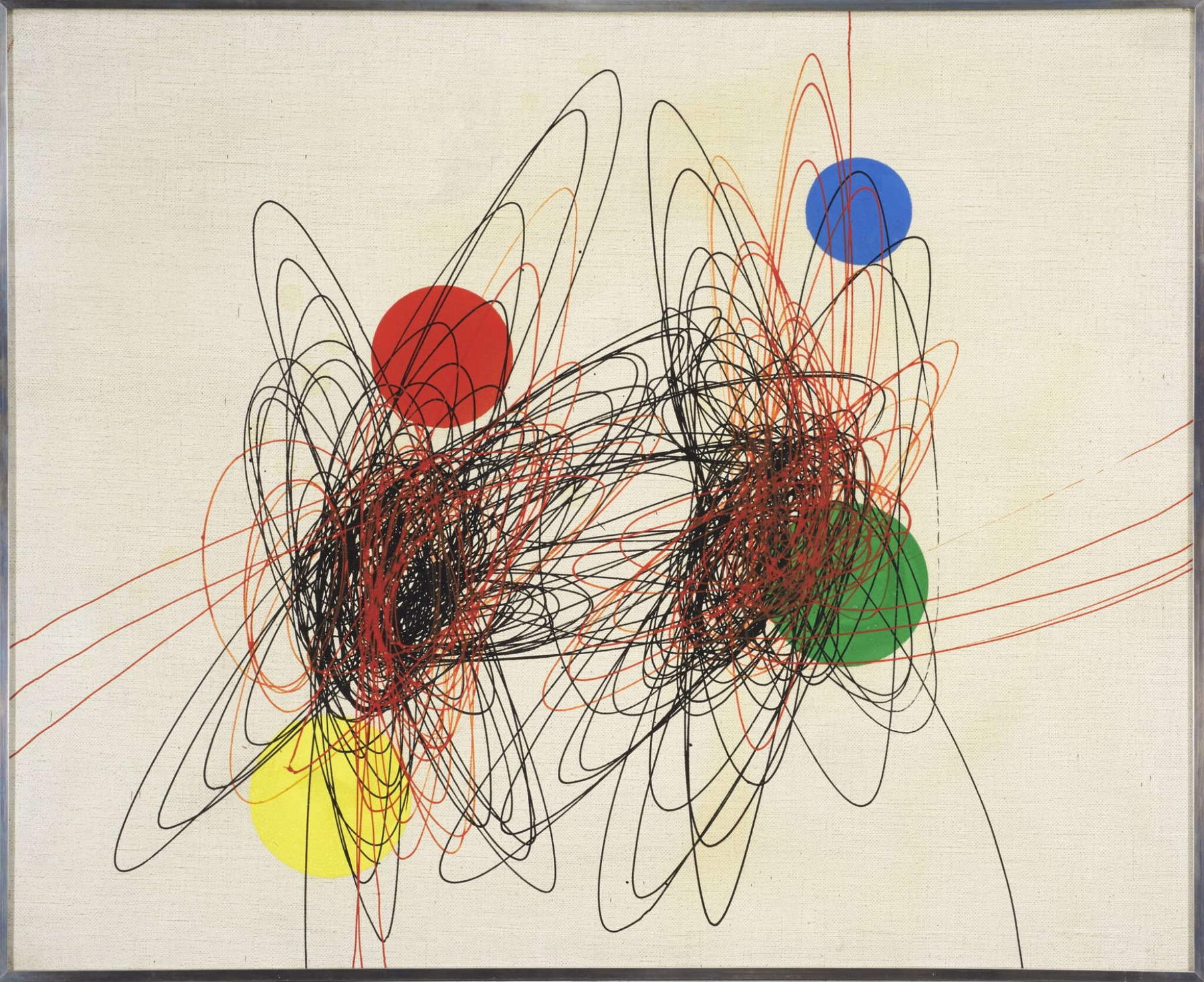

Roberto Crippa soon approached Fontana’s movement, even signing the Proposal for a Regulation, the third manifesto in 1950. During these years his artistic activity focused on Spirals, a series of abstract paintings that reproduced the involutions he practiced aboard his plane. The circular movements produced rays that ideally projected outward from the canvas, constraining its limits. Another artist who supported the movement immediately, from 1947, was Gianni Dova who exhibited at the Galleria del Cavallino and the Galleria del Naviglio, but soon abandoned the current to turn his artistic investigations to a more “nuclearist” painting.

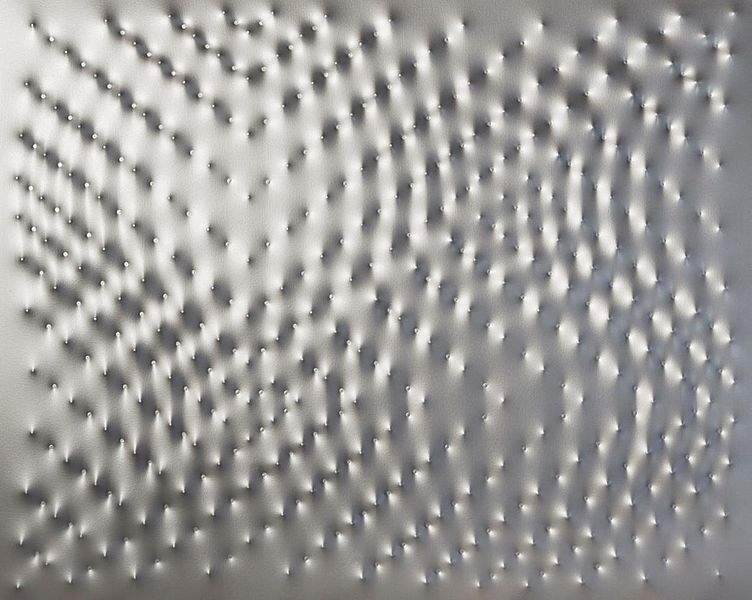

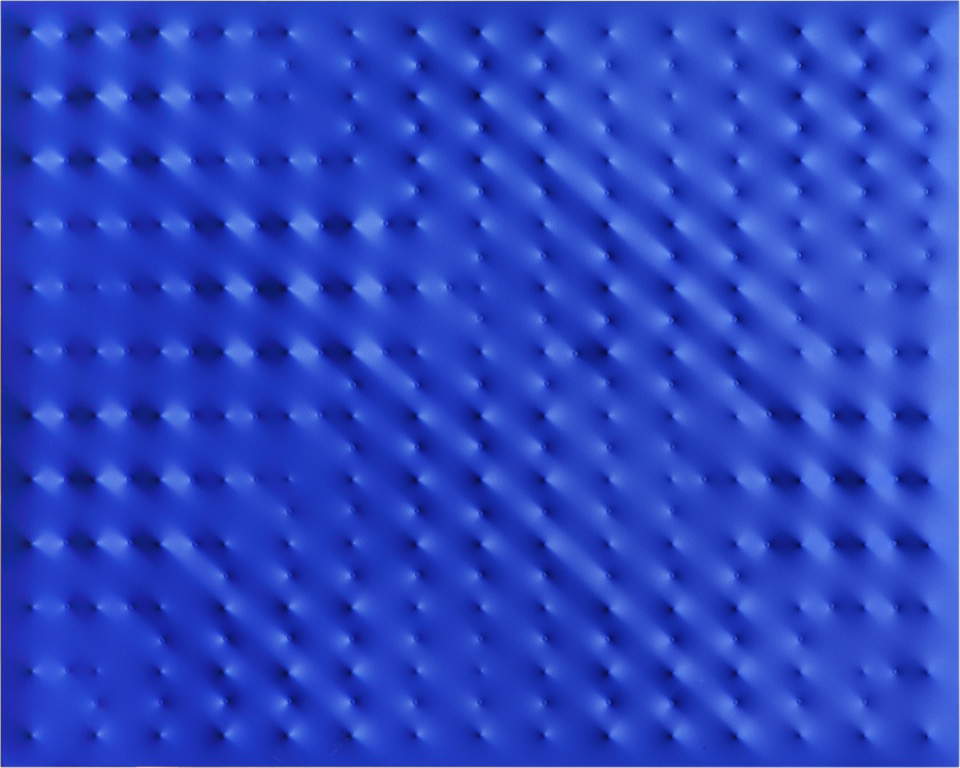

The most important developments in Fontana’s Spatialist investigations found continuity in the work of two artists who did not subscribe to the manifestos but were fascinated by the results of Fontana’s art: Enrico Castellani and Agostino Bonalumi, who expanded and decisively transformed the concept of space in contemporary art. Both worked on the idea of overcoming the two-dimensionality of the painting: this conceptualization of space as an integral part of the work of art profoundly influenced Castellani and Bonalumi. Enrico Castellani, with his relief surfaces, extended Fontana’s research by exploring the possibilities of monochrome and three-dimensionality. Using nails and other tools to deform the surface of the canvas, Castellani created a series of works characterized by an undulating and dynamic surface. This method allowed light to interact variably with the surface, creating plays of shadows and reflections that give a sense of movement and depth, breaking the static nature of traditional painting, and exploring the concepts of rhythm, time, and infinity: his surfaces can almost be considered pieces of infinity that the artist captures and proposes to the viewer, since the patterns followed by the artist are regular and potentially replicable indefinitely.

Bonalumi pursued a further evolution of the spatialist concept. His works, often referred to as “object-paintings,” use underlying structures to deform the canvas in a controlled manner, creating protrusions and depressions that invade the viewer’s space. Bonalumi explored sensory perception and physical space, playing with optical illusion and tangible reality, making the artwork a physical and interactive entity. Both artists thus expanded Fontana’s vision, integrating physical and perceived space into art, and contributing significantly to the emergence of a new three-dimensional aesthetic that has profoundly influenced contemporary art.

|

| Spatialism, origins, theory, styles |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.