In Counter-Reformation Rome, the most illustrious families of the Roman nobility, such as the Borghese, the Aldobrandini, the Ludovisi, the Barberini and others (families from which popes and high-ranking clergymen also came), had begun to develop, in private, a considerable interest in classical antiquity. Many had also begun to set up collections of archaeological finds: in particular, the Farnese created a very rich collection of ancient statues. To house them, they had a gallery built in their Roman palace(Palazzo Farnese) and commissioned the Bolognese painter Annibale Carracci (Bologna, 1560 - Rome, 1609) to decorate it with frescoes. This was the commission that effectively sanctioned the birth of seventeenth-century classicism and that began to outline the dictates of the classicist taste that would dominate all of seventeenth-century Rome and that would know, in addition to Rome, another very important center of diffusion, namely Bologna, from where almost all the classicist artists of the first generations came.

Annibale Carracci, together with his brother Agostino and cousin Ludovico, affirmed the need for art that adhered to the truth, and tried to apply this thought to art with classical subjects as well. An example of this is the Galleria di Palazzo Farnese itself (decorated between 1597 and 1600), where mythological scenes are treated with a compositional freedom and spontaneity that almost leads to the loss of the conception of space and to the rhythmic scansion of the scene resembling that of an ancient frieze, thus at the expense of narrative intent. Therefore, Carraccan classicism magniloquent tones particularly suited to the needs of the patrons. The characters also did not lack a certain amount of naturalism, in line with Carracci poetics.

At the same time, Annibale Carracci arrived at a reinterpretation of landscape painting destined to influence this genre of painting throughout the seventeenth century (artists such as Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain openly referred to the models of the Bolognese painter): in fact, the landscape is no longer the description of a precise place but the description of an ideal place where one can find beauty, the founding canon of classicist poetics. However, this search by Annibale Carracci for ideal beauty in nature (a search that constituted a strong innovation since no one before then sought ideal beauty in nature) did not contrast with his naturalist poetics: in fact, for Annibale Carracci, ideal beauty represented, one might say, the stage of perfection of natural beauty, that is, that which is visible to the eyes. A conception, this, that would later be theorized a few decades later by Giovan Pietro Bellori. And Carracci’s was, moreover, a nature where man is always present, as he too is a participant in the world of nature.

The most important exponent of classicism in the early seventeenth century was Guido Reni (Bologna, 1575 - 1642), who was also the first to embrace the instances of Carracci classicism. Guido Reni was, among seventeenth-century artists, the one in whom the cult of ideal beauty probably reached its peak, and led the painter to be inspired by theart of Raphael Sanzio, whom no seventeenth-century artist probably studied as much as he did. In painting his characters, especially nudes (nudes that found ample space in mythological scenes), the Bolognese artist aspired to give their bodies as much perfection as possible(Samson Victorious, 1611-1612, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale). In the last phase of his career the figures became ethereal and almost metaphysical, so idealized were they. This desire for ideal perfection was underscored by extremely limpid and crystalline painting.

Even Guido Reni, however, was not immune to the typically seventeenth-century problem of the choice between Idea and Nature, a problem that arose, however, from the same basis that found its foundation in the will to react to Mannerism. The reaction could only be conducted in the two ways contrary to Mannerist virtuoso inspiration, that is, by seeking ideal perfection oradherence to truth. The problem, in Rhenish painting, arose especially where the painter had to paint scenes in which bloody or, at any rate, excited action took place. A typical example of the way Guido Reni solved the problem is the Strage degli Innocenti preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna (1611), a work that reveals the artist’s profound reflection on Raphael’s painting. As in Raphael, in fact, the artist brings an extreme simplification of the scheme, with the movement and excitement of the scene taking on a geometric arrangement (particularly here in the shape of an inverted triangle ) and with the feeling of grief expressed in very composed and calm tones.

Different, however, was the approach to classicism of Domenico Zampieri known as Domenichino (Bologna, 1581 - Naples, 1641), who started from the same basis as Guido Reni: the study of ancient art and the great masters, Raphael above all again, and the desire to search for ideal beauty. However, Domenichino turned out to be more attentive to Carracci’s lesson: more spontaneous than Guido Reni, he produced more humanized figures than those of his fellow citizen, and figures in which the search for the characters’ state of mind became more vivid(Reprobation of Adam and Eve, c. 1623, Grenoble, Musée des Beaux-Arts). A state of mind that, however, was communicated more by the characters’ gestures than by their expressions: this expedient made Domenichino’s painting more theatrical than Guido Reni’s (without, of course, achieving those results of spectacularity that would have been contrary to the search for compositional order fundamental to his idea of art).

Domenichino also practiced landscape painting much more than Guido Reni(Paesaggio con guado, 1604, Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj), although in this case he demonstrated a departure from the manner of Annibale Carracci: although his were ideal landscapes, they were often enriched with completely realistic elements that were absent in Carracci’s landscapes.

Alongside these artists came Francesco Albani (Bologna, 1578 - 1660), who was the author of paintings brimming with a highly refined classicism that took on almost courtly and solemn contours(La Primavera, 1616-1617, Rome, Galleria Borghese). A solemnity that was counterbalanced, however, by a lesser compositional ability than that of his contemporaries, resulting in works that were probably less free and characterized by more rigid patterns.

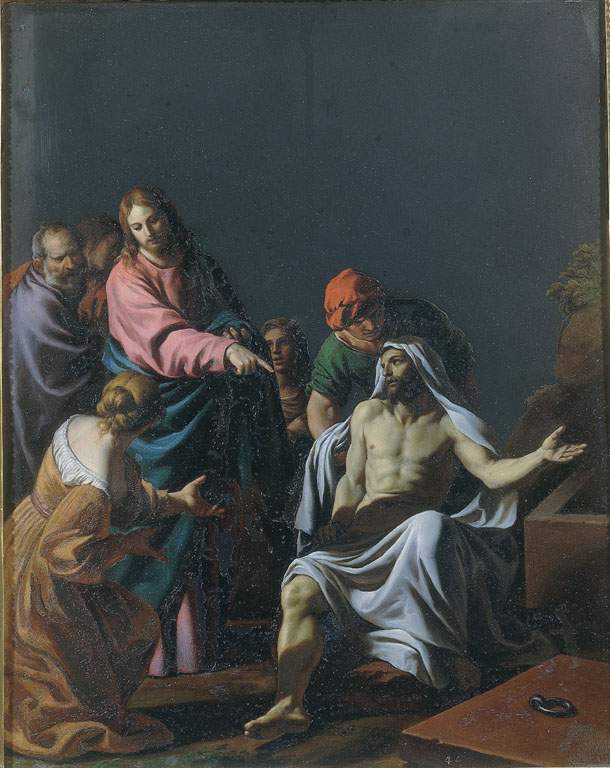

One of the earliest and most important non-Bolognese classicist artists was Alessandro Turchi known as l’Orbetto (Verona, 1578 - Rome, 1649), the author of devotional compositions updated in the style of Ludovico Carracci but which also looked to the common point of reference for all classicist painters of the seventeenth century, namely Raphael. In addition, when he moved to Rome in 1614 (the city where he settled permanently), Alessandro Turchi came into contact with the novelties of Caravaggio’s art, which, only four years after the death of Michelangelo Merisi, was experiencing a particularly fortunate season: however, Caravaggio’s manner did not make much of an impression on the Veronese artist, who did, however, use Caravaggio’s luminism to create effects that enriched his classicist compositions(Resurrection of Lazarus, c. 1616-1617, Rome, Galleria Borghese).

A pupil of Francesco Albani and Ludovico Carracci, on the other hand, was Andrea Sacchi (Nettuno, 1599 - Rome, 1661), who continued to propose his classicist painting composed, simple and made up of few figures at a time when the Baroque language was already fully established (although Sacchi showed, in some of his achievements, to be somewhat contaminated by Baroque art).

Singular, on the other hand, was the iter of an artist like Giovan Francesco Barbieri known as Guercino (Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666), who can be framed more as an artist of transition to Baroque poetics than as a fully classicist painter. Guercino’s production can be roughly divided into three phases: one characterized by production of an almost Caravaggesque matrix (although Guercino never used light to construct forms as Caravaggio did) and softened, however, by the experiences of the Carracci(La Madonna del Passero, 1615-16, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale), a second phase characterized by the elaboration of the so-called Guercinesque macchia, i.e., a technique (mindful of Venetian solutions) according to which forms were constructed through the juxtaposition of real “spots” of color juxtaposed(Vestizione di san Gugliemo, 1620, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale), and a third, more markedly classicist phase(Saul versus David, 1646, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica).

However, Guercino ’s classicism was rather far removed from that of the artists who preceded him: in Guercino there was a lack of that desire to search for ideal beauty (perceptible, however, in his landscape production), but instead there was a certain degree of naturalism in the characters (even in the most classicist paintings) and a search for theatricality achieved either through compositional devices (arrangement of elements in the scene) or through a certain amount of movement inserted into the compositions. These new instances in Guercino’s art made him, as anticipated, a painter who broke away from the more purist classicism and tended instead toward a way of painting that was closer to the dictates of Baroque art.

At the height of the Baroque era, seventeenth-century classicism was carried on by an artist like Giovanni Battista Salvi known as Sassoferrato (Sassoferrato, 1609 Rome, 1685), a pupil of Domenichino who created works characterized by a strong sense of devotion. However, the quest for ideal beauty that had distinguished the classicists of the previous generation had by this time been drained of meaning, so much so that Giovanni Battista Salvi no longer drew on antiquity but observed directly (and perhaps almost solely) the art of Raphael. He thus came to create works that were rather devoid of feeling, bordering almost on imitation, but which were nonetheless characterized by such great sweetness and exceptional clarity as to make Sassoferrato one of the most delicate painters of the seventeenth century(Madonna at Prayer, c. 1640-1650, London, National Gallery).

Last and later exponents of seventeenth-century classicism were Carlo Maratta (Camerano, 1625 Rome, 1713) and Carlo Cignani (Bologna, 1628 Forlì, 1719). Carlo Maratta worked mostly in Rome, gaining such fame that he influenced the style of Roman painting at the end of the century. He, too, looked to Carraccesque and Raphaelesque precedents but could not help but measure himself against the Baroque art that was experiencing its zenith in the very years in which he was beginning to offer his works. The Marche painter’s art thus demonstrated a monumental classicism with scenes characterized by grandiose and magniloquent installations and rich in elements typical of Baroque poetics (e.g., the ubiquitous clouds on which the characters rest or the effects of light), so much so that we often go so far as to label Maratta’s painting as Baroque classicism(Dispute on the Immaculate Conception, 1686, Rome, Santa Maria del Popolo).

Compared to Maratta, Carlo Cignani was, on the other hand, less tempted by Baroque novelties and adhered more to the lesson of his masters (he was a pupil of Francesco Albani): this resulted in a classicism in which the search for the idealization that had distinguished the production of the classicist artists of the early 20th century was renewed. However, in his fresco works, Cignani showed openness to the illusionistic solutions widely used in the Baroque era.

|

| Seventeenth-century classicism: origins and development from Carracci and Maratta |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.