Seventeenth-century Naples was a city characterized by strong contrasts: the capital of the Spanish Viceroyalty, it had been the object, on the part of the Spanish, of a policy of centralization of power that had brought greater wealth and had also brought out the cultural role of Naples. However, it also had to deal with a social reality characterized by social clashes and widespread poverty. It was a city full of contradictions: its problems would lead to the famous Masaniello revolt, which broke out in 1647 and was quelled the following year. In a Naples so full of contrasts, however, there developed a particularly vital artistic fabric, which experienced a remarkable development after Caravaggio stayed in the city in the early seventeenth century: the Lombard painter’s presence gave the necessary impetus to the flourishing of the local school, which in the early part of the century was clearly Caravaggesque in character.

The first artist to absorb the innovations introduced by Caravaggio in Naples was Battistello Caracciolo (Naples, 1578 1635). Trained in a distinctly late Mannerist milieu, Battistello Caracciolo soon learned the Caravaggesque lesson and was the first to disseminate it in Naples through a religious painting in which Caravaggio’s spirit was followed almost slavishly, although he showed that he developed above all the dark component of Michelangelo Merisi(Liberation of St. Peter, 1615, Naples, Pio Monte della Misericordia). This is why Caracciolo’s works are often set in gloomy atmospheres from which the figures emerge thanks to the skillful use of light, which for him, however, was an expedient to highlight the characters and not to build them up as Caravaggio did.

Freer was the adherence to Caravaggism by José de Ribera, also known as Jusepe de Ribera or by the nickname Spagnoletto (Xátiva 1591 - Naples 1652), a Spanish painter transplanted, however, to Naples who developed that realist component of Caravaggio’s art, which proved particularly suited to his talent. Ribera, in fact, had a marked taste for analyzing details. The artist regularly fished for his subjects in the slums of Naples and thus enriched his painting with bizarre characters, full of physical defects, but who were placed in compositions with highly dramatic tones through which the painter wanted to lead the viewer to reflect on the meaning of the paintings(Democritus, 1630, Madrid, Prado).

Another important moment in the development of the Neapolitan school was the sojourn of Artemisia Gentileschi, who arrived in Naples at a time in her career when the dramatic charge of her youthful works had been diluted into a more intimist poetics. Shortly before, moreover, Giovanni Lanfranco and Domenichino had also arrived in Naples, so that for a brief period, between the 1930s and the 1940s, there was a simultaneous presence of the three great artists of the seventeenth century. Another contribution to the reflection on Bolognese classicism was also made by Guido Reni, who stayed in the Neapolitan city for a brief period in the 1920s: thanks to these presences, Naples saw its primacy in the artistic field even more established. Artemisia Gentileschi had a profound influence on a number of painters, the most important of whom were Massimo Stanzione (Orta di Atella, 1585 - Naples, 1656) and Bernardo Cavallino (Naples, 1616 1656), who also showed an openness, however, to the classicism of Domenichino.

Massimo Stanzione was a painter who reflected at length on Caravaggio’s lesson, interpreting it, however, in very delicate tones. In his painting, women, thanks mainly to the influence of Artemisia Gentileschi, became protagonists with their intense expressions and their non-stereotypical but realistic, almost commonplace beauty(Judith with the Head of Holofernes, c. 1630, New York, Metropolitan Museum). Stanzione elaborated a very refined poetics, with limpid colors that mingled with atmospheres characterized by Caravaggesque tenebrism: on this refinement of his played a decisive role the influence of the classicists, above all Domenichino.

Bernardo Cavallino also produced art similar to that of Massimo Stanzione, but at a certain point in his career he made a decisive turn in a more Baroque direction, so much so that it is possible to say that Bernardo Cavallino was, along with Mattia Preti (Taverna, 1613 - Valletta, 1699), the first Baroque artist to work in Naples. In fact, Cavallino showed that he reflected on the painting of artists such as Rubens and van Dyck, but also on the powerful and dramatic colorism of Titian, to elaborate a rather vigorous language marked by a certain degree of dynamism and theatricality(Esther and Ahasuerus, c. 1650, Florence, Uffizi).

Mattia Preti, also known as the Cavalier Calabrese since he became a knight of Malta in 1642, was one of the most successful artists in seventeenth-century southern Italy. He was originally from a small village in Calabria but trained in Rome where he followed his brother Gregorio, a modest painter. In Rome in particular, Mattia Preti reflected on the art of Bartolomeo Manfredi and the Manfrediana methodus, so much so that his early productions are all very careful depictions of daily life in seventeenth-century Rome, a Rome made up of taverns, soldiery, and gamblers(Partita a dama, c. 1630-1635, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum). His art therefore was not unlike much contemporary production, although Mattia Preti revealed an uncommon capacity for naturalistic investigation equal only to that of the greatest artists of the time.

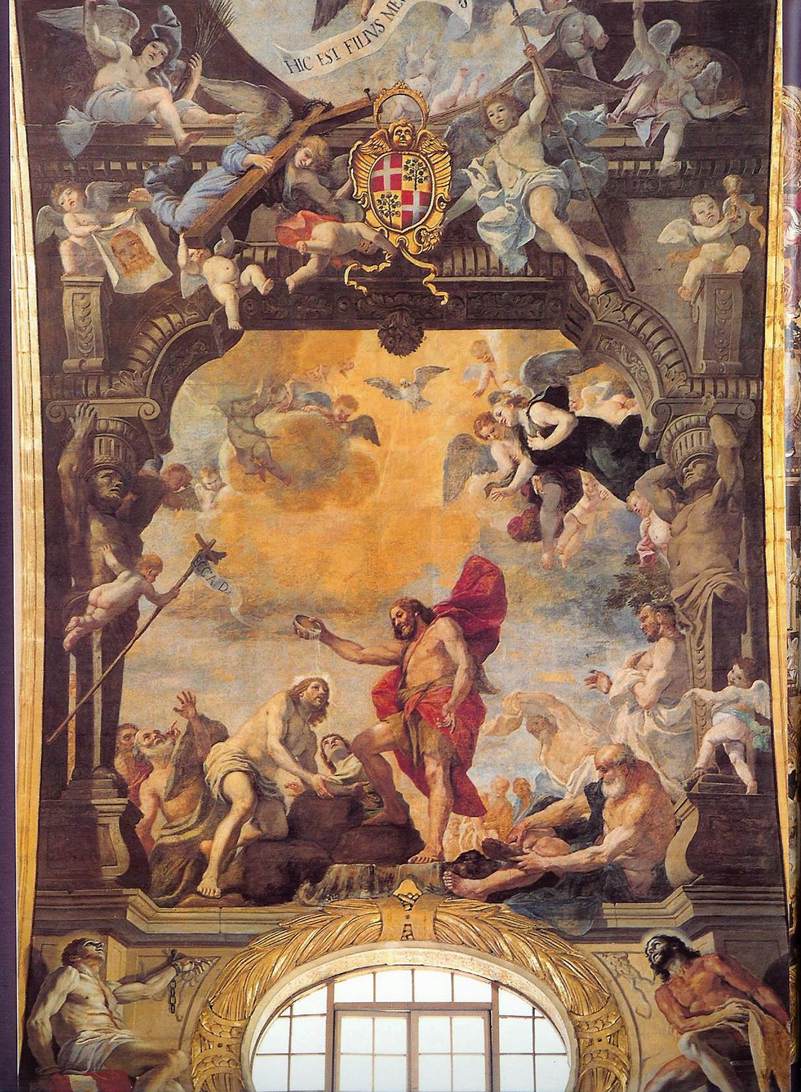

After studying the works of the classicist painters (above all, once again, Domenichino), and following his stay in Genoa where he came into contact with Luca Cambiaso’s luminism, evident especially in the paintings he made in the Ligurian city itself, Mattia Preti elaborated a more monumental language, characterized by more vigorous forms and greater theatricality(Clorinda frees Sofronia and Olindo from the stake, 1646, Genoa, Palazzo Rosso), which later led the artist’s style to blossom into the Baroque. Mattia Preti offered a first test of these tendencies in the frescoes of Sant’Andrea della Valle in Rome, where he was able to take advantage of Pietro da Cortona’s advice: however, his first Baroque experiment ended in failure, due to the fact that his exceptional gigantism resulting from a personal and too hasty interpretation of Cortonism was not appreciated by his contemporaries. Reflecting on his mistakes, however, the artist came to demonstrate, in his maturity, a Baroque style of solemnly celebratory and illusionistic implantations, which, as in Pietro da Cortona, made use of quadratures and light effects to extend the spatiality of the frescoes to infinity: a style, this one, most evident in the frescoes he painted in Malta for the Valletta Co-Cathedral (1661-1666).

Seventeenth-century Naples also saw the presence of an offbeat artist such as Salvator Rosa (Naples, 1615-Rome, 1673), one of the most original, innovative, peculiar, and bizarre artists of the entire seventeenth century and perhaps even of the entire history of art. In Naples he began his career under the sign of José de Ribera’s painting, but after meeting Giovanni Lanfranco, who had advised him to move to Rome, he went to the capital of the Papal States where he became acquainted with the art of the Dutch painters present in the city but also with that of Caravaggio, and also in Rome he was an important protagonist of the city’s cultural life. Salvator Rosa in fact was an eclectic artist: a painter but also a singer, musician, and writer, so much so that his Satires constitute one of the most interesting writings of the time also because they give us insight into the artist’s thoughts on many aspects of life at the time. Salvator Rosa in particular was very critical of the powerful, who were guilty of dissipating huge amounts of money in frivolities and reserving very little for the poor.

Alongside Caravaggesque paintings, Salvator Rosa developed a very particular landscape painting. Meditating on the classicist landscape paintings of artists such as Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, the Neapolitan artist revisited what had been produced until then to propose landscapes where nature is no longer idyllic and idealized but becomes wild and disturbing, the buildings are often in ruins, the sea stormy(Seascape with ruined tower, c. 1645-1650, Florence, Palazzo Pitti). A painting that in many ways proved to anticipate the landscape painting of Romanticism that developed in the19th century.

Another strand of Salvator Rosa’s painting was that of the fantastic and monstrous. In fact, the artist often produced scenes with witches’ sabbaths, demonic presences or creepy creatures (such as the terrifying monster of the Temptations of St. Anthony, shown here in the version in the Pinacoteca Rambaldi di Coldirodi, San Remo, c. 1645-1649). Salvator Rosa developed this taste for the horrid inspired by some Dutch paintings of magic and alchemy, in open contrast to the classicist painting of his time, to affirm all the contradictions of an era marked by strong social contrasts. In this sense, it could be said that Salvator Rosa’s painting was the visual expression of his literary activity, but also an extreme implication of the taste for the drama of Baroque art, which found in his work unattainable heights of bizarreness. What’s more, the witchcraft scenes, at a time when modern scientific thought was being born, could also be an attempt to confer artistic dignity through a precise and intentional aesthetic of the horrid on popular beliefs that, in the eyes of a man of culture, could only seem absurd.

|

| Seventeenth-century art in Naples and southern Italy |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.