Sandro Botticelli (Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi; Florence, 1445 - 1510) is one of the iconic artists of the Renaissance, and in particular of the Florentine Renaissance, not only for the proverbial beauty of his goddesses and Madonnas, but also for many other reasons: a character of great culture(read here an in-depth look at his illustrations for the Divine Comedy), he was one of the finest painters of his time (although he was also capable of decidedly more muscular paintings than those with which his name is generally associated), he was the artist who perhaps more than any other gave shape to the ideals of Neoplatonic philosophers(read here an in-depth look at the development of Neoplatonism in Medici Florence), was the Medici painter par excellence, was able to demonstrate great gifts by trying his hand at a wide variety of subjects (from mythological paintings to sacred scenes, from the large altarpiece to the small panel for private devotion, from portraits to the tondo), and was also an artist who found himself living between two eras: the last years, those of the religious crisis, were in fact the years of the fall of the Medici and the rise and subsequent fall of Savonarola. Botticelli is an artist symbolic of the Renaissance, then, not least because with him a certain ideal of Renaissance art reaches its zenith and at the same time ends its parabola.

Botticelli’s career took place almost entirely in the Florence of Lorenzo the Magnificent: the artist, in fact, began to work on his own from 1469, a year that coincided with the beginning of the seigniory of the Magnifico, a figure of considerable importance(read here an in-depth look at ten masterpieces commissioned by him) not only on a political level but also on a cultural level, the Magnifico having been a great patron of artists and men of letters, who gathered in his court gave rise to a fervent circle of intellectuals (from Marsilio Ficino to Cristoforo Landino, from Pico della Mirandola to Luigi Pulci, from Poliziano to Demetrio Calcondila, passing through artists such as Pollaiolo, Verrocchio, Ghirlandaio, Botticelli himself, Filippino Lippi and a very young Michelangelo Buonarroti). Botticelli thus lived through the most luminous moment of the Florentine Renaissance: the end of the Medici seigniory would mean for him a profound crisis that would lead him, in the last years of his life, to completely change his orientations and then also to stop his career as an artist.

His baton was inherited by only one important painter, Filippino Lippi, a restless painter where, however, the lesson of Botticelli could still be read: however, with the master gone, a season had already ended, and his works were soon forgotten. At the time when Botticelli’s star was fading, those of artists such as Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci were already shining, already at the top of their careers and able to steer trends, tastes and ideas in very different directions from those in which Botticelli had moved. Who nevertheless remains one of the fundamental painters of the 15th century.

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, later called Botticelli perhaps because of the nickname of his brother Giovanni (who was called “Botticello” because he was corpulent), was born in 1455 in Florence’s Via Nuova to Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, a leather tanner by trade, and his wife Smeralda. He was initiated into the art probably by his brother Antonio, a goldsmith by trade. In 1459 he became a pupil of Filippo Lippi, with whom he collaborated on the frescoes in Prato Cathedral. In 1466, following Filippo Lippi’s departure for Spoleto, Sandro moved to Verrocchio’s workshop and around 1467 executed the Madonna della Loggia, one of his earliest known works. In 1470 he opened his own workshop and in the same year obtained his first public commission, the figure of the Fortress for the Tribunale della Mercanzia: this is also his first documented work. Two years later, Filippo Lippi’s 15-year-old son Filippino became Sandro’s collaborator. In the same year the artist joined the Compagnia degli Artisti di San Luca. In 1474 he executed another public work, an Adoration of the Magi for Palazzo Vecchio that has been lost. In the same year he is in Pisa where he takes over from Benozzo Gozzoli as director of the Camposanto frescoes but leaves the post after a very short time. The following year he was commissioned to make the designs for the wooden inlays of Federico da Montefeltro’s studiolo in the Ducal Palace in Urbino, and around the same year he executed theAdoration of the Magi preserved in the Uffizi.

In 1477, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici commissioned his great masterpiece, the Primavera. It is unclear when Sandro finished the work, perhaps around 1482. In 1480 he was commissioned by the Vespucci family (the same as the famous Simonetta Vespucci often referred to as Botticelli’s muse: however, this is a story rooted in the nineteenth century and of which there is no evidence, read more here) to execute the Saint Augustine for the church of Ognissanti. In 1481 he was commissioned by Pope Sixtus IV to create some fresco scenes in the Sistine Chapel together with other great artists of the time-Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, Luca Signorelli, Bartolomeo della Gatta. Around 1482 he executed instead the Madonna of the Magnificat preserved in the Uffizi. In about 1484 he painted the Birth of Venus.

The climate changed in Florence in 1489, the year in which Girolamo Savonarola’s sermons began: Sandro was greatly impressed. In 1492 Lorenzo the Magnificent dies: this is the beginning of Sandro’s artistic decline as he enters a phase of mysticism a partly because of Savonarola’s sermons. In this climate, around 1495, he painted Apelles’ Calumny, after which, in 1501, he executed his last work: the Mystical Nativity, which is also his only dated and signed work. In 1504 he was part of the commission that was to deliberate on the placement of Michelangelo’s David , while in 1505 he was enrolled in the Compagnia di San Luca. Sandro Botticelli died in Florence on May 17, 1510. He is buried in the church of Ognissanti.

Sandro Botticelli’s career began in the sign of his masters, above all Filippo Lippi and Verrocchio, as seen in the Madonna della Loggia, one of his earliest known works. Coming from Filippo Lippi’s lesson are the grace, lyricism, and taste for the marked outline: these are elements that Botticelli reworks, reinterprets, and makes into true “trademarks” of his painting. In the Madonna of the Loggia we also notice suggestions derived from Verrocchio’s lesson, particularly the realistic rendering of certain details, such as the decorations of the robes and the architecture: Verrocchio’s art was one of the most naturalistic in Florence at the time and was based on a vibrant, realistic (a term that must obviously be weighed against the era), attention to detail representation.

Even before he devoted himself to mythological painting for which he is universally known, Botticelli in fact excelled in religious art. TheAdoration of the Magi conserved in the Uffizi, a masterpiece from around 1475 commissioned by the banker Gaspare Zanobi del Lama, and where a probable self-portrait of Sandro Botticelli can also be discerned (the blond young man on the right, wearing a gold dress), is the painting through which the painter definitively procured the graces of the Medici (the patron was part of the Medicientourage ). It is in fact a work that emphasizes the role, prestige and power of the seigniory and the family that ruled it (in the procession of the Magi, in fact, Botticelli also includes portraits of some members of the Medici family). Also famous are Sandro Botticelli’s Madonnas, and in this regard one of the best and most celebrated examples is the Madonna of the Magnificat, also in the Uffizi (it takes its name from the hymn, the Magnificat, that the Madonna is writing on the book that the two angels hand to her). Note the detail of the Child Jesus placing his arm over his mother’s to guide her in her writing, to make her even more a part of this union with divinity. This is a tondo of great elegance, beauty and refinement, capable of great success even at the time: the graceful faces of the characters, the contemplative expression of the Infant Jesus, that of the Madonna absorbed in writing the incipit of the Magnificat, the richness and fineness of the decorations of the garments, the crown, the golds, the calligraphy with which the hymn is written, the landscape behind the figures, the skilful use of outline, and the precious colors denote, as well as the perseverance of the Lippesque lesson, the elegance and meticulousness of the artist in outlining every single detail. It is, moreover, one of the first works in which the artist begins to show signs of the mystical crisis that would later overwhelm him after the fall of the Medici.

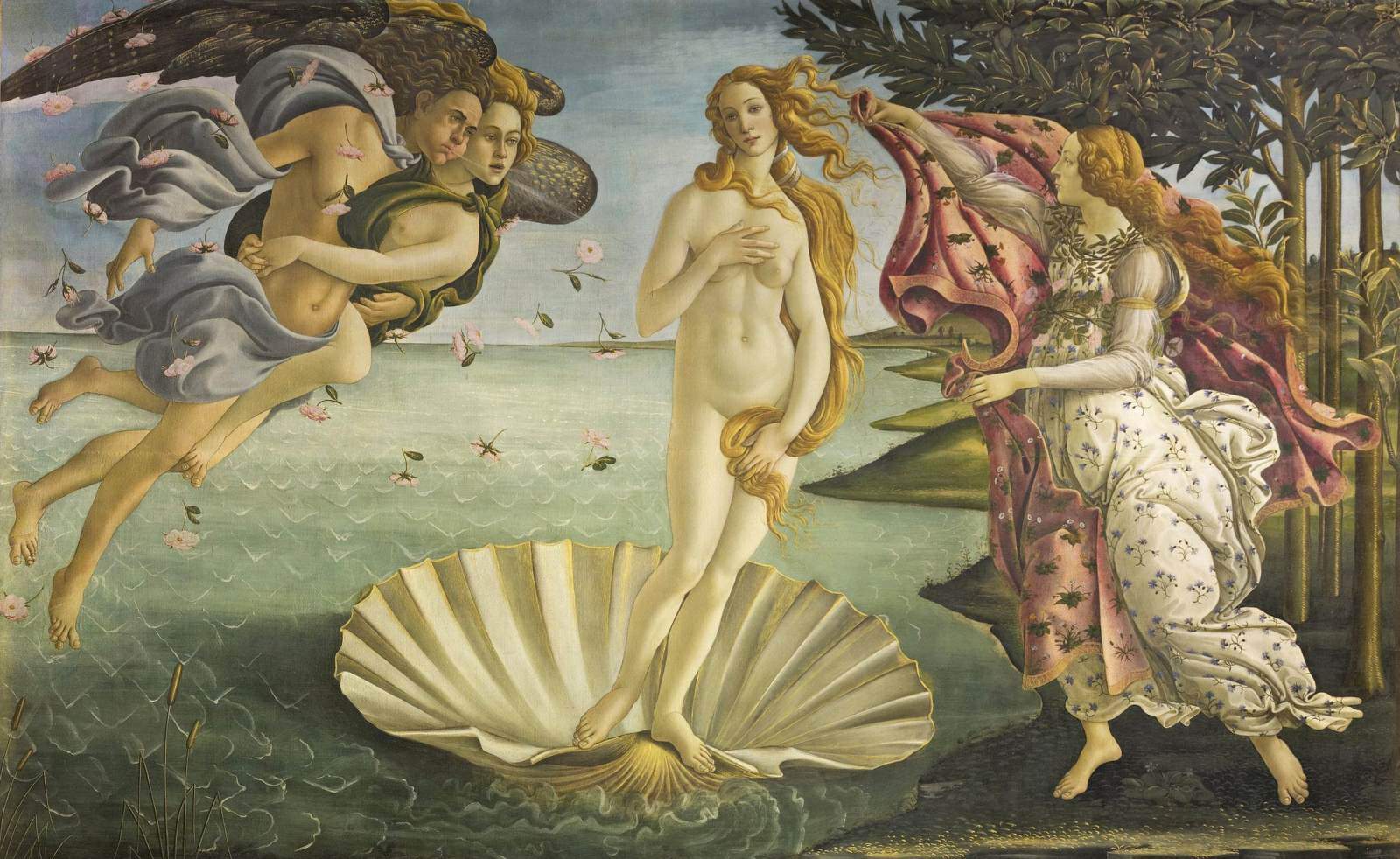

Botticelli’s name, however, is mainly associated with the Birth of Venus and Primavera. The Primavera, the older of the two (it was commissioned from Botticelli in 1477 by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de Medici, cousin of the Magnifico), features several characters who, according to the traditional (though not humanistically accepted) identification: read here an in-depth discussion of a recent alternative proposal) are, from the left, Mercury, the three Graces, Venus and Cupid, the wind Zephyrus, the nymph Chloris, and finally Flora, that is, Chloris transformed as a result of her union with Zephyrus (Flora is the personification of Spring itself), all set in a lush garden where botanical experts have identified some two hundred different plantspecies (read here an in-depth discussion of plant species in Spring). The painting depicts the reign of Venus, described on the basis of an iconographic program perhaps developed by Poliziano on the basis of the texts of classical authors, above all Horace and Ovid. Sandro Botticelli was, in fact, part of a circle of intellectuals who were active at the court of the Magnifico, and who ranged in different fields, from art to literature via philosophy, and were united by Neoplatonic ideals. In a letter he wrote to the commissioner of the Primavera, the philosopher Marsilio Ficino recommended that he be inspired by Venus, the embodiment of the ideal of Humanitas on which all humanism is based. This interpretation, formulated by Ernst Gombrich, would attribute a pedagogical purpose to the painting, since Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco at the time of the commissioning was 14 years old, and this would also explain the other figures because Venus-Humanitas elevates man from the senses, symbolized by the trio on the right, to lead him to contemplation, symbolized by Mercury, by passing through reason, that is, the three Graces. In contrast, according to Charles Dempsey, spring would represent nothing but the season itself: Zephyrus, Chloris and Flora symbolize the month of March, Venus, Cupid and the Graces the month of April and Mercury the month of May. Other scholars also hypothesize spring as a symbol of the pax medicea: at that time, Florence was experiencing a season of peace, and it was the Medici’s dream to defend it for as long as possible. Finally, according to Erwin Panofsky, the painting could be an allegory of spiritual love, while on the contrary, the Birth of Venus would be, according to the same scholar, a symbol ofearthly love.

The Birth of Venus possibly dates from 1484 and was also executed for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici: although the work is universally known as the Birth of Venus, what we see is not the birth of the goddess in the strict sense, but instead the arrival on the island of Cyprus, sacred to the goddess, after her birth. Again, the theme is inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses and a modern take on it probably suggested by Poliziano. Like Spring, Birth of Venus is a painting of uncertain date and whose meaning eludes: it has therefore been the subject of various interpretations. According to Panofsky, the painting would represent earthly love: Venus, nude, is in the center of the composition in the pose of the Venus pudica (thus a classical quotation) and standing on the shell, while on the left Zephyrus and Chloris arrive under a shower of roses carried by the spring wind, while the figure on the right, the one who hands the beautiful mantle with flowers to the goddess, is one of the Hours, the personification of the seasons according to Greek mythology, and in particular this would be Spring. As in the case of Spring, Venus could still allude to the ideal of Humanitas and thus echo the philosophy of Marsilio Ficino: in particular, the nudity of the goddess would refer to the purity of the soul. Some speculate that instead Sandro Botticelli had intended to reproduce Venus Anadiomene (“born of the sea,” an attribute of the goddess), a work of classical antiquity executed by the Greek painter Apelles. A Christian-based interpretation wants the painting as the birth of the soul from the water of baptism. And again, there are those who have read the Birth of Venus as a representation of love, with passion, sensuality and eroticism symbolized by the couple on the left and chastity symbolized by the Now who wants to protect the nakedness of the goddess, who in turn embodies both sensuality and chastity, since she is naked but at the same time covers her pubis. The Birth of Venus, moreover, is one of the few paintings by Sandro Botticelli to have been executed on canvas instead of panel, which was the medium most commonly used in the 15th century.

The climate of tension that engulfed Florence after the fall of the Medici is reflected in an allegorical work preserved in the Uffizi, Apelles’ Calumny, although it is not known to whom exactly it refers, that is, it is not known who the slanderer is: some think it may be Botticelli himself, others think it may be a friend of his, but in any case it may be a painting that arose in the political context of Savonarola’s Florence. Apelles, a painter who according to tradition depicted Calumny in the terms that would later be taken up by Botticelli, was allegedly slandered and responded to his slanderers by making an allegorical painting. To create the painting, Botticelli relied on written sources and reconstructions, particularly a description by Leon Battista Alberti in his De Pictura, a description in turn taken from the Greek author Lucian. Botticelli faithfully follows the narrative: starting from the right we meet on the throne the king, usually identified as King Midas, painted with donkey ears, an attribute that emphasizes his ignorance. The two female figures whispering in the king’s ears are Ignorance and Suspicion, while the slanderer is the young man who is dragged by the hair by the female figure holding a torch in her left hand: the latter is Slander, and the torch could be either a symbol of her fury or of false love for the truth. The figures styling the hair of the Slander are Fraud and Insidiousness, signifying that in appearance the Slander appears to be telling the truth because he presents himself with good looks. The ugly man in rags who holds her hand and asks the king to be heard is Livor, which thus drives Calumny. The Remorse (also identified by others as the Penance) is depicted as an old woman hidden under long, worn black and white robes, watching the Truth, naked, looking skyward as if to say that that is where justice will come from. It is a highly symbolic work, full of classical citations (statues and reliefs that might even ironically allude to scenes of justice), characterized by heightened dynamism and tension: it is a painting that marks a clear division between the Botticelli “Medici,” so to speak, and the Botticelli of late maturity.

The work-symbol of the later Botticelli is the Mystical Nativity, dated 1501 (it is Botticelli’s only dated and signed work), kept at the National Gallery in London. Date and signature are found in the Greek inscription accompanying the painting, which also alludes to the events of those years, including an explicit reference to theApocalypse of St. John. The painting is perhaps an allegory of peace, to which the olive branches carried in the hands of the angels in flight would also allude, established by Christ’s advent on earth. This is a fundamental work because it is the pictorial manifesto of this phase of Botticelli’s career: a painting that is the bearer of all his anxieties due to the influence on him of Savonarola’s sermons, a painting that also manifests a certain archaism (the Madonna, for example, is larger than the other figures, in an unrealistic way: a typical mode of hierarchical depiction in medieval painting). It is a painting imbued with mysticism and restlessness, the work of a painter whose career was now heading for decline, at a time when other great artists, such as Leonardo and Michelangelo, were beginning to establish themselves.

To learn about Sandro Botticelli’s art, it is essential to travel to Florence, where his major masterpieces are located. The best known are at the Uffizi, where you can see the Birth of Venus, the Primavera, the Madonna of the Magnificat, the Madonna of the Loggia, theAdoration of the Magi, Pallas and the Centaur, the Fortress, the Return of Judith to Bethulia and several others. Works such as the youthful Madonna and Child, Two Angels and John the Baptist and the Madonna of the Sea can be admired at Accademia Gallery, while the Pitti Palace holds the Portrait of a Young Man and the Portrait of a Young Woman, and also in Florence, one can see the St. Augustine in the Study in the Church of Ognissanti. Other Italian museums that preserve works by Botticelli are the Museums of Palazzo Farnese in Vicenza (the tondo with the Madonna and Child and St. John the Baptist), the Carrara Academy in Bergamo (the Portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici), the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan (the Madonna of the Book and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, the latter among the key works of late Botticelli), and the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan (the Madonna of the Pavilion).

Not everyone knows that Sandro Botticelli also frescoed the Sistine Chapel: there where one usually goes to see Michelangelo, one can also admire, on the side walls, three scenes by Botticelli, namely the Trials of Moses, the Punishment of the Rebels and the Trials of Christ. Abroad, museums that hold works by Botticelli are the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the National Gallery in London (where there are two masterpieces such as Venus and Mars and the Mystical Nativity), the Prado in Madrid (where three of the four episodes of the story of Nastagio degli Onesti are located), the Louvre, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, and the Fogg Art Museum (the Symbolic Crucifixion).

|

| Sandro Botticelli, life and works of the iconic Renaissance artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.