Rosso Fiorentino, life, works and style of the great Mannerist painter

Together with Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino (Giovanni Battista di Jacopo; Florence, 1495 - Fontainebleau, 1540), is the key figure of early Florentine Mannerism: the two painters, about the same age, had the same training (they were both pupils of Andrea del Sarto) and proposed a distinctly new painting, outside the box. Rosso Fiorentino’s reality is a decidedly alienated disturbing “nonreality”: his works are peopled with grotesque, alienating, bizarre figures, often marked by bewildered or worried looks, and by the total breakdown of the balance and harmony that were one of the main achievements of the Renaissance. In a world as unsettled and full of restlessness as the world of the early sixteenth century was, Rosso Fiorentino’s painting reflects all the concerns of the man of the time.

Rosso Fiorentino (so nicknamed because of the color of his hair) was a highly original artist, intolerant of rules, who proposed a personal style that was outside the canons: and that Giovanni Battista di Jacopo was a rebellious, restless and tormented painter is evident from his training, because Giorgio Vasari himself, in his Lives, states that Rosso did not like the art of his contemporaries, except for “a few masters” (it is Vasari himself who adopts this expression) whom he wanted to follow instead, and among these few masters appreciated by the painter were Andrea del Sarto, an important point of reference for young painters of the time in Florence, and Michelangelo Buonarroti (Vasari points out that important for Rosso Fiorentino’s training was Michelangelo’s cartoon of the Battle of Cascina, which Rosso Fiorentino copied at a young age: read a detailed discussion of the Battle of Cascina here).

For being one of the main figures ofMannerist art and, along with Pontormo, the initiator of Mannerism in Florence, Rosso Fiorentino can be placed among the great names in the history of Italian art. His work exerted a major impact on many later artists: for example, Giorgio Vasari, Giulio Romano, Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli, Francesco Granacci, Francesco Primaticcio, Andrea Lilio, and several others.

|

| Giorgio Vasari and aids, Portrait of Rosso Fiorentino (fresco; Arezzo, Casa Vasari). Photo by Francesco Bini |

The biography of Rosso Fiorentino

Giovanni Battista di Jacopo was born in Florence in March 1494, a couple of months earlier than his “alter ego,” Pontormo (who was instead a native of Pontorme, a suburb of Empoli). We do not know much about the painter’s family: we know that his father Jacopo was a native of the Val di Chiana and that his brother Filippo was a friar in the church of Santissima Annunziata. Il Rosso, a nickname derived from the color of his hair (it seems, moreover, that Giovanni Battista was a very handsome man), would complete his training with Andrea del Sarto, and the study of Michelangelo’s Battaglia di Cascina would be fundamental for him. In 1512, when he was not yet eighteen years old, he and Pontormo painted the predella of Andrea del Sarto’sAnnunciation of San Gallo. The painting by the one who was Rosso’s master is now preserved in the Pitti Palace, while the predella by his two pupils has been lost. Rosso was confirmed as an artist of precocious talent when in 1513, at the age of nineteen, he began painting his first work that can be dated with certainty, the fresco of theAssumption in the basilica of Santissima Annunziata in Florence, which would be finished the following year.

In 1515 Rosso was involved in the preparation of the preparations for the festivities on the occasion of Pope Leo X’s arrival in Florence. In 1517 he enrolled in the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali, while the following year he produced, for Leonardo Buonafede, the work known today as the Spedalingo Altarpiece, preserved in the Uffizi, one of his best-known and most famous masterpieces, although the work’s decidedly unusual appearance led the commissioner to dislike it. Around 1520 the artist was in Piombino where he worked for the local lord, Jacopo V Appiani, although we do not know for sure the dates of his stay. In 1521 Rosso Fiorentino is in Volterra, where he paints his greatest and most famous masterpiece, as well as the cornerstone of all Mannerism and the history of Italian art: the Deposition now in the Pinacoteca Civica in Volterra. Also in Volterra he executed the Villamagna Altarpiece. In 1522, for the Dei family, he painted the Dei Altarpiece now in the Uffizi. Again, around 1523 he painted one of his best-known masterpieces, Moses and the Daughters of Ietro. In the same year he moved to Rome where he worked on the Cesi Chapel in the church of Santa Maria della Pace, the same place where Raphael Sanzio had worked a few years earlier. In 1527, during the sack of Rome, he was taken prisoner by the Germans, but later managed to free himself and took shelter in Perugia. In the same year he reached the town of Sansepolcro, where he painted the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, another key work in his production, also known as the Deposition of Sansepolcro.

In 1528 Rosso Fiorentino was in Città di Castello where, for the local cathedral, he painted Christ in Glory. On Maundy Thursday 1530 he is involved in a fight that broke out in a church in Sansepolcro, where Rosso Fiorentino and one of his apprentices are forced to confront some priests (the grotesque episode is recounted in Vasari’s Lives ). The artist decides to go to Venice, where he is welcomed by his friend Pietro Aretino (whom he probably met in Rome), and then leaves for France, a place where, according to Giorgio Vasari, the painter had always expressed a desire to go. In France, Rosso Fiorentino became court painter to Francis I. In 1532, for Francis I of France, he began directing work on the so-called Gallery of Francis I in the castle of Fontainebleau, which was to be decorated with a series of frescoes. He was involved in the project until 1539, and in the same year he began, together with Francesco Primaticcio (Bologna, 1504 - 1570), to work on the frescoes of the Loves of Vertunno and Pomona, which were finished the following year. The artist died suddenly, aged only forty-six, on November 14, 1540, in Fontainebleau. The cause of death is not known with certainty: according to Vasari, the painter allegedly committed suicide, feeling a strong sense of guilt for having unjustly accused a painter friend of his, Francesco di Pellegrino, of theft, who was also later tortured in prison. Vasarian information, however, is not confirmed by any other source (and for the same reason, namely the absence of documents on the subject, it cannot be refuted either). All his building sites and commissions were inherited by Primaticcio, who continued Rosso’s work, giving rise to the so-called Fontainebleau school, which introduced Italian Mannerism to France thanks to the presence of some leading figures.

|

| Rosso Fiorentino, Assumption (1517; fresco, 385 x 337 cm; Florence, Santissima Annunziata, Chiostrino dei Voti) |

|

| Rosso Fiorentino, Shovel of the Spedalingo (1518; tempera on panel, 172 x 141.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

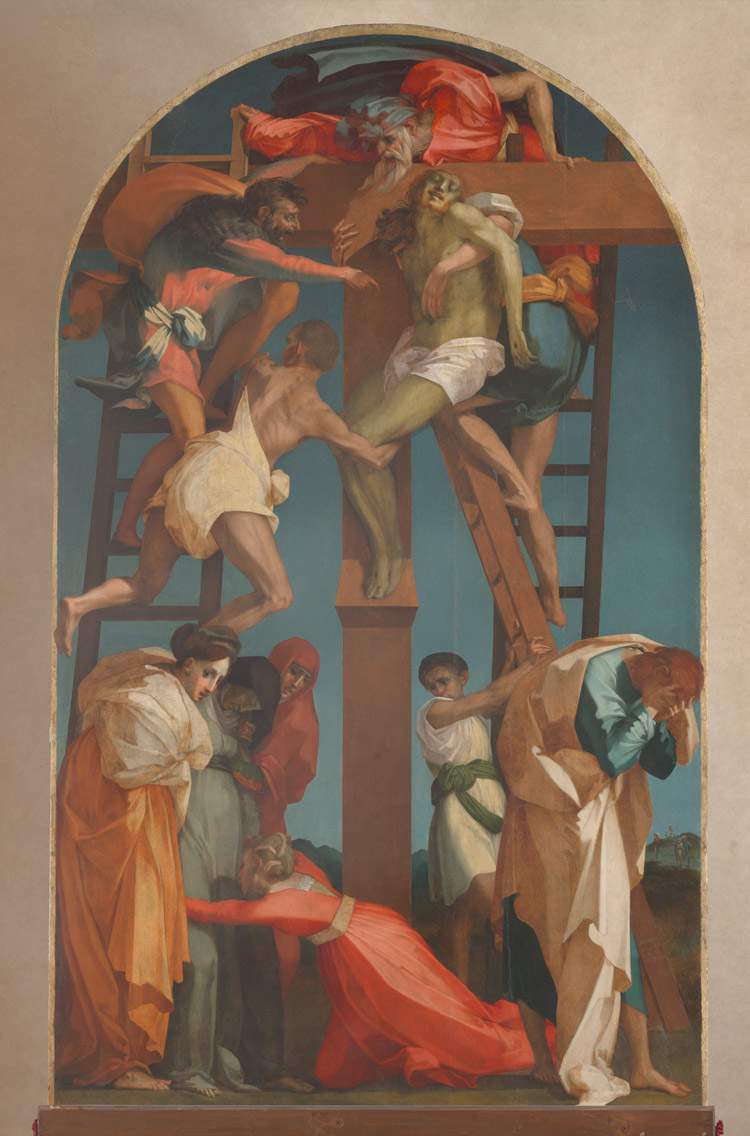

| Rosso Fiorentino, Deposition from the Cross (1521; oil on panel, 343 × 201 cm; Volterra, Pinacoteca and Museo Civico) |

Rosso Fiorentino’s style and major works

Rosso Fiorentino’s first certain work is theAssumption of the Virgin made between 1513 and 1514, when the artist was just eighteen years old, and found in the so-called Chiostrino dei Voti, a courtyard of the basilica of Santissima Annunziata in Florence in whose fresco decoration all the greatest artists of the time participated, starting with Rosso’s own master, Andrea del Sarto (it is plausible that Rosso Fiorentino’s participation in the undertaking was advocated by Andrea del Sarto himself, who at only twenty-seven years old was already one of the most prominent artists in Florence at the time). Rosso’s fresco is divided into two registers, the upper one in which the Madonna is observed to be ascending to heaven amid a jubilation of angels, and the lower one in which the apostles are noted to be astonishedly watching the scene, for a compositional scheme that recalls that of Fra’ Bartolomeo’s Last Judgment. Alongside the vigor of the figures, which recalls the art of Michelangelo, and the chromaticism that instead harks back to the art of Andrea del Sarto, in this Assumption it is already possible to notice many of the traits that will be peculiar to the art of Rosso Fiorentino, such as the way of treating the draperies, which are very wide (they almost always appear wider than they should be) and with angular shapes (one of the many oddities that distinguish the Florentine painter’s style). TheAssumption is also notable for the modernity with which the artist arranges the figures of the apostles, which are not rigid and schematic, but take on different poses and angles. Again, it is important to observe the drapery of the central figure: the green mantle that comes out of the frame within which the painting is placed constitutes a motif that breaks harmony and balance (elements that will be the basis of the birth of Mannerism).

An even more original Rosso Fiorentino and even more directed toward Mannerism can be seen in the so-called Pala dello Spedalingo, a work from 1518 now in the Uffizi. It is so called because it was commissioned from him by Leonardo Buonafede, an important monk in Florence at the time and “spedalingo,” or rector of the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, who was destined to become bishop a few years later. The altarpiece should have been placed in the church of Ognissanti, but it was not liked and therefore was not displayed in the church (it was instead sent to the church of Santo Stefano in Grezzano, a hamlet of the town of Borgo San Lorenzo). Regarding the painting, Vasari tells an anecdote that Leonardo Buonafede, going to the painter’s studio to see how the work was progressing, fled in horror because the saints looked like devils to him. We do not know if this was actually the case, but this story very eloquently communicates the originality of Giovanni Battista di Jacopo’s art. Indeed, the figures, particularly those of saints advanced in age such as St. Anthony Abbot and St. Jerome, appear strongly ungainly: St. Jerome, for example, is hunched over, has a skeletal body and a pair of hands (especially the left) with fingers that look more like claws. A saint, therefore, with a grotesque appearance. The other saints, namely St. John the Baptist on the left and St. Stephen next to St. Jerome, have looks and expressions that are anything but joyful and calm: they look astonished and restless, each looking in a different direction, and the very heavy shading around the eyes (look at those of the Infant Jesus, for example) contribute to making the saints’ slightly flushed faces even more disturbing.

Rosso Fiorentino’s best-known work, however, is the Volterra Deposition: in fact, after the experience of the Spedalingo Alt arpiece, the artist left Florence (although we do not know if the move is related to the affair of the altarpiece), and was first in Piombino, then in Volterra where he executed two works: the Villamagna Altarpiece, now in the Diocesan Museum of Volterra, and the grandiose Deposition preserved today in the Pinacoteca Civica (it was made for the Compagnia della Croce of Volterra and was placed in the compagnia’s chapel inside the church of San Francesco). With the Deposition, Rosso Fiorentino signed one of the most important works in the history of Italian art, a milestone of Mannerism. With his Deposition, exactly as Pontormo would do a few years later, Rosso Fiorentino aims to strangle the viewer by subverting harmony and balance: Mannerism denies the rules of the Renaissance, it is contrary to any logic of realism and verisimilitude, it is a reflection of the era of strong contradictions and political upheaval in which this movement was born (and consequently the artists were affected and began to transfer all their anxieties and restlessness onto canvas). In Rosso Fiorentino’s Deposition there is no lack of spatial references (they would have been lacking in Pontormo’s Deposition ), although the ladders leaning against the cross are placed asymmetrically, but the drama and sense of disquiet are conveyed to the relative by the concussed and agitated movements, the physical aspects of the characters, their completely unrealistic poses, the very bright colors, and the extremely angular and very unrealistic depiction of the draperies. In addition, the choice of having the light come from one side (i.e., from the right side of the composition) causes some portions of the robes to have very bright hues and those in shadow to be very dark, without gradual transitions from light to shadow, an expedient that lends a sense of greater drama to the scene, as if the emphasized movement of the protagonists, as well as their almost grotesque gestures, were not already enough. And, in this regard, the cries of the characters who are removing the body of Jesus from the cross are interesting on the one hand, and on the other the cries of despair of the characters below, with Magdalene theatrically falling to embrace the Madonna’s legs and St. John instead striding toward the viewer holding his face in his hands (it seems, moreover, that the saint conceals a self-portrait of the painter: according to what Vasari relates, Rosso was a young man of beautiful appearance). Then there is another detail that contributes to making the whole even more alienating: the painter, in fact, decided to insert, in the lower right corner, some figures that apparently have nothing to do with the scene (they are three characters that appear near the hill, dressed in contemporary clothes, which in photographic reproductions are barely noticeable but if one observes the work live at a close distance they are easily noticed). It can be assumed that they are soldiers and thus have to do with the story of the Passion of Christ (they would be, therefore symbolic of evil).

Other important works include the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the Church of San Lorenzo in Sansepolcro: the work was commissioned by the Confraternity of the Battuti for the Oratory of the Holy Cross, and was later moved to its present location. Completed in 1528, the painting is among the most disturbing of Rosso Fiorentino and of all Mannerism. The tones become dark, gloomy, the blue sky disappears, and Rosso introduces the dark background: these tones convey an idea of the dramatic experience the painter had in 1527 during the sack of Rome, so much so that the absolute most disturbing element of the painting, namely the soldier behind the fainting Madonna, looks monstrous, because the soldier in the context of the Passion of Christ symbolizes evil. Moreover, here Rosso Fiorentino probably also wants to condemn the experience he had in Rome the year before. The restlessness is therefore different from that which animated the Volterra Deposition: if in Volterra Rosso divided the painting into two registers, creating a contrast between the two planes, the upper one of fatigue and the lower one of despair and pain, here the whole group of participants is animated exclusively by pain and it is only on pain that Rosso’s attention is focused. Again, in Umbria, in Città di Castello, the painter executed between 1528 and 1530 the Risen Christ in Glory, a work made for the Corpus Christi company and intended for the town’s cathedral, while today it is kept in the local Museo Diocesano. The figures close to Christ are Magdalene, Our Lady, St. Anne, and St. Mary of Egypt, while below are a variety of figures representing different trades as well as peoples of the world (also noted are a gypsy woman and a black character, peoples who were saved by the sacrifice of the dead and risen Jesus and to whom the message of Christ himself is therefore intended). The work did not receive much appreciation, because according to the mentality of the time the inclusion of such bizarre characters in a work of art of this kind was difficult to accept, and then also because a painting such as this, which was meant to express serenity and joy at Christ’s resurrection, was still made with dark tones and atmospheres reminiscent of those of the Sansepolcro Deposition. Again, the rejection of tradition and harmony, figures that always accompanied Rosso’s art, prevails.

|

| Rosso Fiorentino, Pala Dei (1522; oil on panel, 250 x 299 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Palatina Gallery) |

|

| Rosso Fiorentino, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1528; oil on panel, 270 x 201 cm; Sansepolcro, San Lorenzo) |

|

| Rosso Fiorentino, Risen Christ in Glory (1528-1530; oil on panel, 348 x 258 cm; Città di Castello, Museo Diocesano) |

Where to see Rosso Fiorentino’s works

Few paintings by Rosso Fiorentino remain to us. A good number of Giovanni Battista di Jacopo’s works can be found in Florence: in the Tuscan capital is theAssumption in the Chiostrino dei Voti of Santissima Annunziata, several works in the Uffizi (the Spedalingo Altarpiece, theAngiolino musicante, the Ritratto di Giovani in nero, the San Giovannino, and the Moses defending the daughters of Ietro). The Palatine Gallery in Palazzo Pitti, on the other hand, preserves the Pala Dei, while at the Basilica of San Lorenzo one can admire the Marriage of the Virgin. To get to know Rosso Fiorentino’s art, however, it is essential to go to Volterra, to admire the Villamagna Altarpiece and especially the Deposition, his greatest masterpiece. Still in the region, it is possible to admire the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the church of San Lorenzo in Sansepolcro.

Outside Tuscany, few places host works by Rosso Fiorentino. In Città di Castello is the Risen Christ, while the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples holds a Portrait of a Seated Young Man with Carpet. The later masterpieces are all outside Italy: there are the frescoes in the Gallery of Francis I in Fontainebleau, the Bacchus, Venus and Love at the Musée National d’Histoire et d’Art in Luxembourg, and the last masterpiece, the Pieta, made in France and kept in the Louvre. Other works kept outside Italy include the Madonna in Glory of 1517 (at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg), theAllegory of Salvation (at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), the Holy Family with St. John at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, the Portrait of a Young Man at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Dead Christ Mourned by Four Angels at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Death of Cleopatra at the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig, Germany.

|

| Rosso Fiorentino, life, works and style of the great Mannerist painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.