Romanticism: European origins and development, themes and styles of the great painters

Romanticism was a wide-ranging international literary, philosophical and artistic movement that arose in Europe between the late 18th century and about the middle of the 19th century, spreading rapidly in reaction to the firm rational ideal upheld by the Enlightenment, and in opposition to the academic artistic conditioning of neoclassicism.

In the arts, inheriting the awareness of individual rights that the 18th century had won and was celebrating with the French Revolution (1788-1799), parallel to a growing poetics of feeling, the power of expressive freedom,imagination and personalintuition asserted itself. To reason, scholastic study and classicist harmony, the creative capacity and subjectivity of the artist were added, affirming the profile of the nonconformist creative genius , as it later came to be regarded throughout the 20th century, whose creative spirit is more important than strict adherence to formal rules and traditional procedures. Romantic sensibility had different outcomes and chronologies in each cultural area, but with a common predilection for landscape and the world of history, including contemporary history, considered from a psychological and internalized perspective and with specific inclinations towardfantastic and visionary evocation and spiritual and sentimental values.

Origins and development of Romanticism

Romantic art developed in Germany and then spread to France, England as well as Italy, investing mainly in painting, although it also gave impetus to a new understanding of sculpture, architecture and music and derived from an inescapable literary feeling. The artists who considered themselves part of the movement shared an attitude toward artistic practice, nature and humanity, not relying on strict definitions or principles. Romantic artists in each discipline found a voice in many genres and varieties of styles, being able to lighten themselves from the academic dictates and tastes that chased classical canonical beauty in most European countries, to explore instead their own states of mind and proclaim each their own position and originality.

The fundamental attitudes of Romantic artists were: a deep appreciation of the beauties of nature; a general exaltation of emotion over reason and of the senses over the intellect; a retreat into the self and a thorough examination of the human personality, its states of mind and mental potentialities; a preoccupation with the genius, the hero and the exceptional figure in general and a focus on his inner passions and struggles; an emphasis on the imagination as a gateway to transcendent experience and spiritual truth; an interest in popular culture, national and ethnic cultural origins, and the medieval period; and a predilection for the exotic, the remote, the mysterious, the strange, the occult, the monstrous, the sick, and even the satanic.

The historical terms of the Romantic period can be understood between the fall of the Napoleonic empire, when with the Restoration monarchical absolutism returned to reign in Europe, to become dominant in the 1820s and until about the 1940s, when the art movement of Realism raged from France, with due exceptions in the various countries.In the aftermath of Napoleon’s military defeats, an anachronistic attempt to return to the Ancien Régime (“Old Regime”) was rampant, contrasting the ideas of the French Revolution (1788-1799).Instead, Romanticism supported the struggles for freedom, equality and justice, and was closely linked to the emergence of nationalism, responding to imperial universalism with the uniqueness of the various European monarchies. Indeed, there was a need to recognize each country’s right to manage itself independently in the name of the homeland, emphasizing local traditional values, for which art became a spokesman by stimulating national identity and pride.

Local folklore, traditions and landscapes, formed the visual imagery for many Romantic painters who shed light on social injustices through their dramatic compositions, rivaling the more serious neoclassical history paintings accepted by national academies, to which they infused a call for social and spiritual renewal.

As the absolute and unquestionable value of classical rules was going to be replaced by the free creativity of thought, Romanticism also coincided with the liberal tendencies of the first half of the 19th century, which led to the frequent insurrectional uprisings, culminating in those of 1848, which saw almost all of Europe fighting against its sovereigns and which, in Italy, took shape in the first war of independence up to the Risorgimento era. TheRomantic artist lived intensely through all the even political events of his time, proving himself a rebel against legalitarian conformism. In an attempt moreover to react to the crushing industrialization, the arts expressed the symbolic values of that cultural period, such as the need for the individual to be reunited with nature and with an idealized, mostly medieval past, as an example of a society governed by a Christian ideal of simplicity and moral integrity, by virtue of a newfound nineteenth-century spirituality. In fact, the term Romanticism is derived from “romance,” which denoted literary compositions such as medieval chivalric novels that depicted fantastic events within historical settings and scenarios.

In Germany in the decades 1770-1780, an especially literary pre-Romantic cultural current, known as “Sturm und Drang” (Storm and Impetus), had emerged, which advocated the valorization of the styles of the Middle Ages and German spiritual history, and a vocation to the ideals of the irrational, the myth of nature, the emotions and fantasy, claiming the right of man to fulfill his intimate aspirations without imposed laws and conventions. It was an experience of great impact and influence on public and artistic consciousness, which went on to spread to other nations. The most representative painters of the Romantic movement were Caspar David Friedrich in Germany, William Turner and John Constable in England, and Jean-Louis-Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix in France. Italy, too, had an important exponent of so-called historical Romanticism in Francesco Hayez.

Themes and styles of the great European painters

In many countries, Romantic painters turned their attention to nature and outdoor painting. Works based onclose observation of the landscape, sky and atmosphere elevated and promoted the genre to a new level. Some artists emphasizing humans as one with nature, others depicting the power and unpredictability of nature over humans. In each case devoting themselves to depicting the subjective reaction, the inner life in relation to the surrounding nature.

In fact, the philosophical aesthetic concept of the “sublime,” introduced in the mid-eighteenth century by the English philosopher Edmund Burke and taken up in 1790 by the German philosopher Emanuel Kant, became widespread, understood as that feeling of awe and dismay in the face of nature and all those things in the world, not necessarily related to beauty, capable of emotionally overwhelming us. The experience of the sublime triggered a crucial reflection for Romanticism, as can be seen in the painting produced along these lines. The interest in the transient phenomena of the natural world led painters to devote themselves to a careful study of light andatmosphere and their effects on the landscape. The concern to preserve the spontaneity of the impression led to a revolution in painting technique, with the rapid notation of the sketch then reproduced in the final composition.

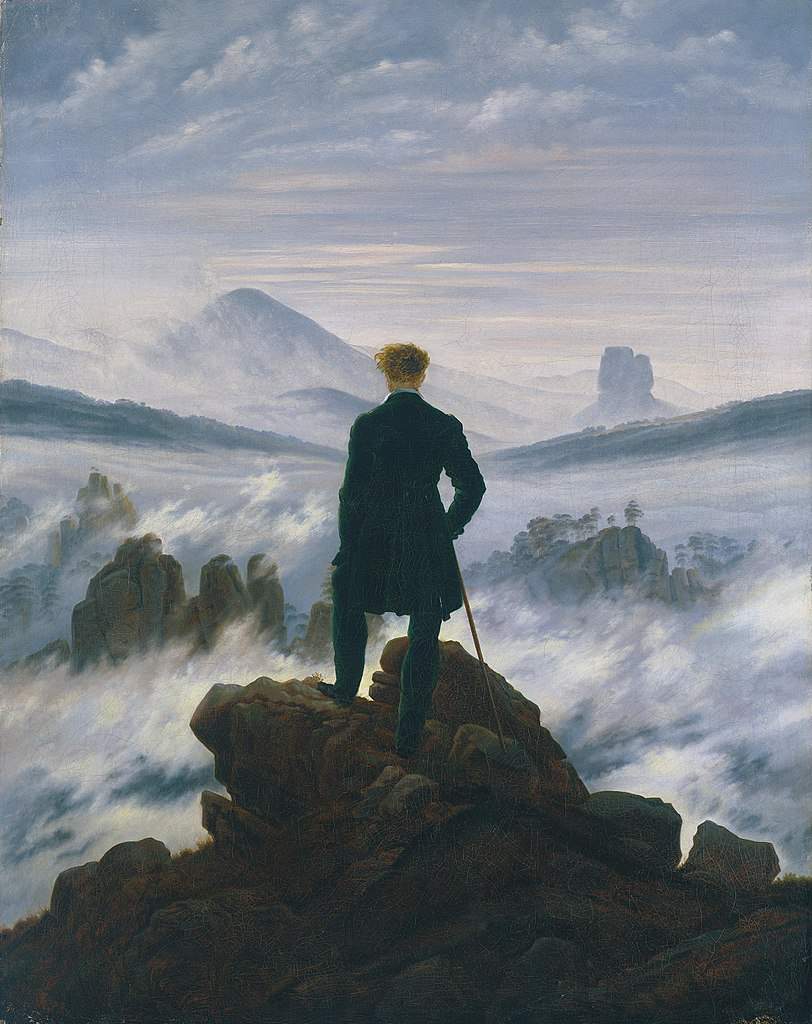

In Germany, the leading Romantic artists focused precisely on painting natural landscapes. II most important was Caspar David Friedrich (Greifswald, 1774 - Dresden, 1840), a painter who succeeded in translating onto canvas man’s relationship with the forces of nature, understood as a divine, sublime and monumental manifestation.With his paintings, landscape painting became an allegory for the human soul, as well as a symbol of freedom and boundlessness that subtly criticized the political narrowness of the time. Friedrich procured a revolutionary break with the traditions of Baroque and neoclassical landscape painting. He never simply replicated an objective view, but rather provided an opportunity to contemplate the presence of God in natural works, fascinated by the symbolic and allegorical power of earthly elements seen as a religious emanation.

To the natural themes and motifs he combined human presence, mostly with his back to the viewer, and a sense of spirituality, especially through allegories of loneliness, death, ideas about the afterlife and hopes for salvation, opening up largely unknown pictorial contexts. The motif of the “Rückenfigur” includes the viewer in the process of interpretation ( The Wayfarer in the Fog of 1818 is famous), a solitary human figure seen from behind, caught contemplating the landscape in front of him that allows the viewer of the work to identify with the character in the work. One of the key ways in which German Romanticism differs from French and British Romanticism. With his attitude as a melancholy painter prone to a mystical religiosity Friedrich helped solidify the image of the Romantic artist par excellence. His dedication to landscape painting as an alternative to traditional religious or history painting encouraged his contemporaries to reconsider the genre with excellent results.

English Romantic painters also favored landscape. Their depictions were not as dramatic and sublime as their German counterparts, but were more naturalistic, emphasizing more bucolic landscapes. These artists emphasized the transient effects of light, atmosphere, and color to portray a dynamic natural world capable of evoking awe and grandeur. John Constable (East Bergholt, 1776 - London, 1837) was among the most influential English landscape painters, combining careful observation of nature with deep sensitivity, and rebelling against the standard practices of the academy. His use of color, with juxtaposed, vibrant patches, was influential on the great French landscape painters, such as Eugène Delacroix, who was inspired by Constable for his unmistakable rendering of shimmering light with touches of white.

Color was also explored even more radically by William Turner (Covent Garden, 1775 - Chelsea, 1851), among the greatest English painters of all time. Turner was a prolific but eccentric and reclusive artist who worked in oils, watercolors, and prints. By applying color in increasingly rapid strokes, he created a kneaded, dynamic surface that earned him the epithet “painter of light,” instrumental to the Impressionists in the late 19th century. And while Constable painted the freshness of nature, Turner captured its grandeur and, as with the German Friedrich, depicted man’s bewilderment in the face of the majesty of his phenomena. In Turner’s works, the traditional landscape dissolves into undefined forms that cancel out the texture of objects, immersing the viewer within the painting.

Unlike their German and English colleagues, the French painters had a wider repertoire of subjects, including portraiture and history painting, suggesting rather man’s desire to conquer nature. Inasmuch, the spirit of the French Revolution greatly stimulated interest in depicting contemporary historical events, and artists sought to authentically represent the crucial moments of their time. The Enlightenment’s rule of reason was perceived as limiting and mechanistic, consequently they turned to scenes of rebellion and protest. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars with Napoleon in exile, they began to challenge the neoclassicism of personalities such as Jacques Louis David, the most prominent painter during the Revolution. If the neoclassical heroic figures were idealized and posed, with the Romantics they were depicted dynamically, in top battling moments.

Artists Théodore Géricault (Rouen, 1791 - Paris, 1824) and Eugène Delacroix (Charenton-Saint-Maurice, 1798 - Paris, 1863) led and developed the French Romantic movement. Their painting arose from real life and depicted, as with the landscape painters, transient moments, movement and dynamism in scenes constructed with monumental tones and metaphorical elements of the feelings of humanity at the time. Important masterpieces such as Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819), inspired by a true account of a shipwreck, and Delacroix’s The Boat of Dante (1822), brought Romanticism to the attention of a wider, international audience. Both paintings scandalized the Paris Salons where they were exhibited, in 1820 and ’22. Deviating from the favored neoclassical style and using contemporary subjects, they outraged the Academy and the general public. The depiction of emotional and physical characteristics and various psychological states would become hallmarks.

Géricault entered art history with his depictions of collective dramas, individual heroism and suffering, as in the series of portraits of ordinary and humble people, the poor, the elderly and the insane depicted with unparalleled intensity and expressiveness. After Géricault’s untimely death in 1824, Delacroix became the leader of the Romantic movement because of his emphasis on color as a mode of composition and his use of expressive brushstrokes to convey feelings. His use of color was rich and sensuous, his compositions dynamic and his subjects exotic and adventurous, ranging from North African Arab life following an inspirational trip of his own to revolutionary politics at home. An important example of this is the large and well-known canvas Liberty Leading the People, which was created in connection with the Parisian revolutionary uprisings of July 1830, in which the artist took part, representing what he experienced firsthand, beyond his narrative imagination.

Also in Italy, the greatest exponent of Romanticism painting, Francesco Hayez (Venice, 1791 - Milan, 1882) was known for themes drawn from Italian history and subjects from the past, in a period of transition between neoclassical and freer Romantic visual culture. He produced symbolic, brightly colored works of high patriotic value, with truthful historical reconstructions, political references and sentimental accents, demonstrating a new sensibility in dealing with historical subjects. One example is the painting of a medieval scene Sicilian Vespers (1846). His repertoire also includes portraits of famous figures of his time, as well as well-known works such as The Kiss (1859), which demonstrate the primacy of the sentimental poetics of that era.

|

| Romanticism: European origins and development, themes and styles of the great painters |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.