René Magritte (Lessines, 1898 - Brussels 1967), nicknamed “le saboteur tranquille” because of his ability to succeed in insinuating doubts about reality, is considered one of the greatest exponents of Surrealism, so much so that he is considered one of the fathers of the Surrealist movement. Surrealism, an avant-garde of which he was a member, is an artistic movement born in France in the 1920s, from the very beginning it presented itself as arevolutionary avant-garde that went beyond reality thus emphasizing a new dreamlike dimension made up of dreams, paranoia, free associations, and madness, thus freeing the unconscious from mental constraints. The most influential artists of the movement besides Magritte are Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Man Ray, and Yves Tanguy.

Despite the depiction of seemingly realistic subjects, Magritte’s greatness lies in the transformation of the everyday into illusion and dreams by unearthing unusual meanings and declaring open war on reason. Magritte’s works consequently push beyond the rational, crossing the thresholds of the ordinary in a humorous key. “Reality is never as we see it: truth is above all imagination”: through this famous statement by the painter we can perfectly frame the artist’s thinking, noting in him a desire to always find new forms of suggestion of reality, continuing to question where the boundary between real and fiction lies. Admired by the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio De Chirico, he implemented a new language based on evasion from reality.

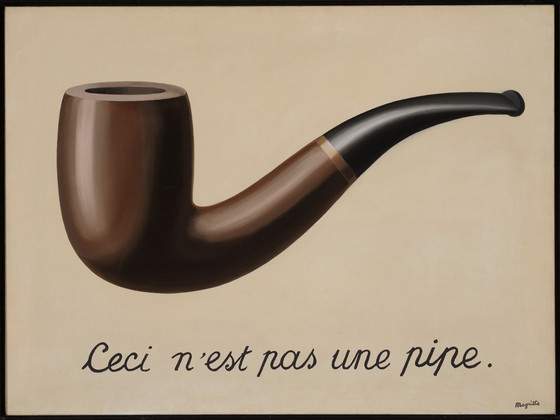

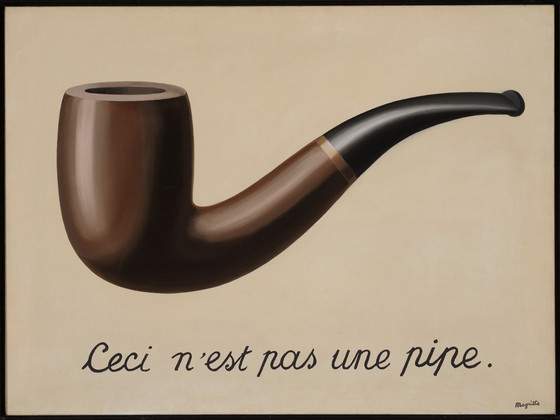

Magritte is best known today for his work La Trahison des Images (1928-29), a painting depicting a pipe and a caption quoting the phrase “ceci n’est pas une pipe,” which invites the viewer to deep reflection on what the real object really is and what representation is. No matter how realistically the object is represented, it is unable to fulfill its function, which is to be smoked, and that is why it cannot be defined as a pipe. All of Magritte’s works thus focus on the contrast between reality and fiction, between the rational and the irrational, between realistic and dreamlike representation, between the ordinary and the mysterious.

|

| René Magritte |

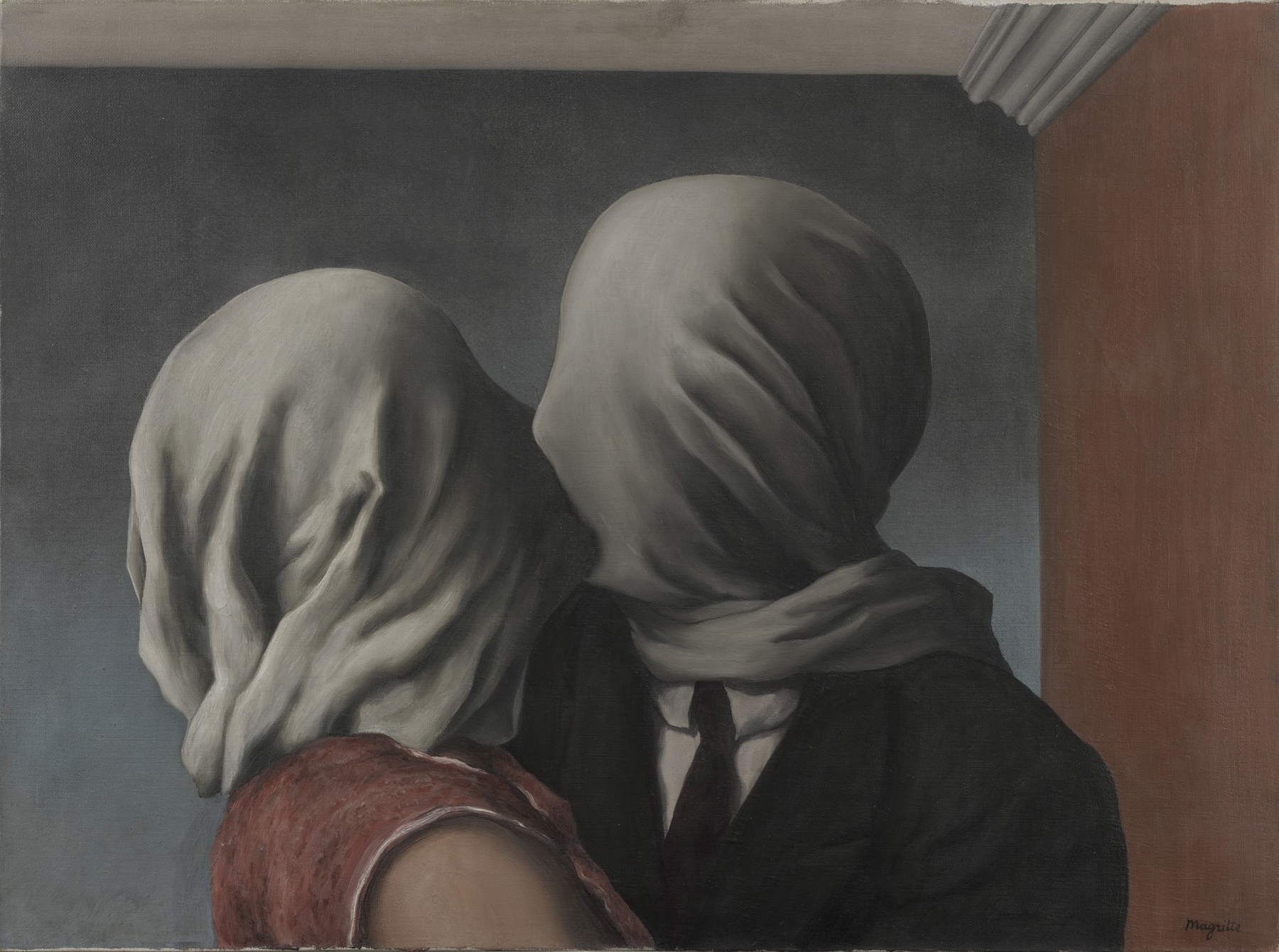

René Magritte was born in Lessines, a small Belgian town, on November 21, 1898. His childhood is marked by numerous relocations and especially by the suicide of his mother, who in 1912 decided to take her own life by throwing herself into the Sambre River, being found with a shirt wrapped around her face. This traumatic event profoundly influenced the painter’s artistic activity to the extent that he depicted in several paintings(L’histoire centrale and Les amants), figures with their faces completely covered by a white veil.

Moving to the city of Charleroi, Magritte will keep his childhood traumas at bay while trying to start a new life. He thus began classical studies and later focused on painting. Following his great passion, he will decide to enroll in 1916 in theBrussels Academy of Fine Arts where he will begin to become interested in avant-garde movements such as Cubism and Futurism. Having completed his academic studies in 1922, he married Georgette Berger, his partner since high school, and in 1923 began his first job as an advertising graphic designer instead.

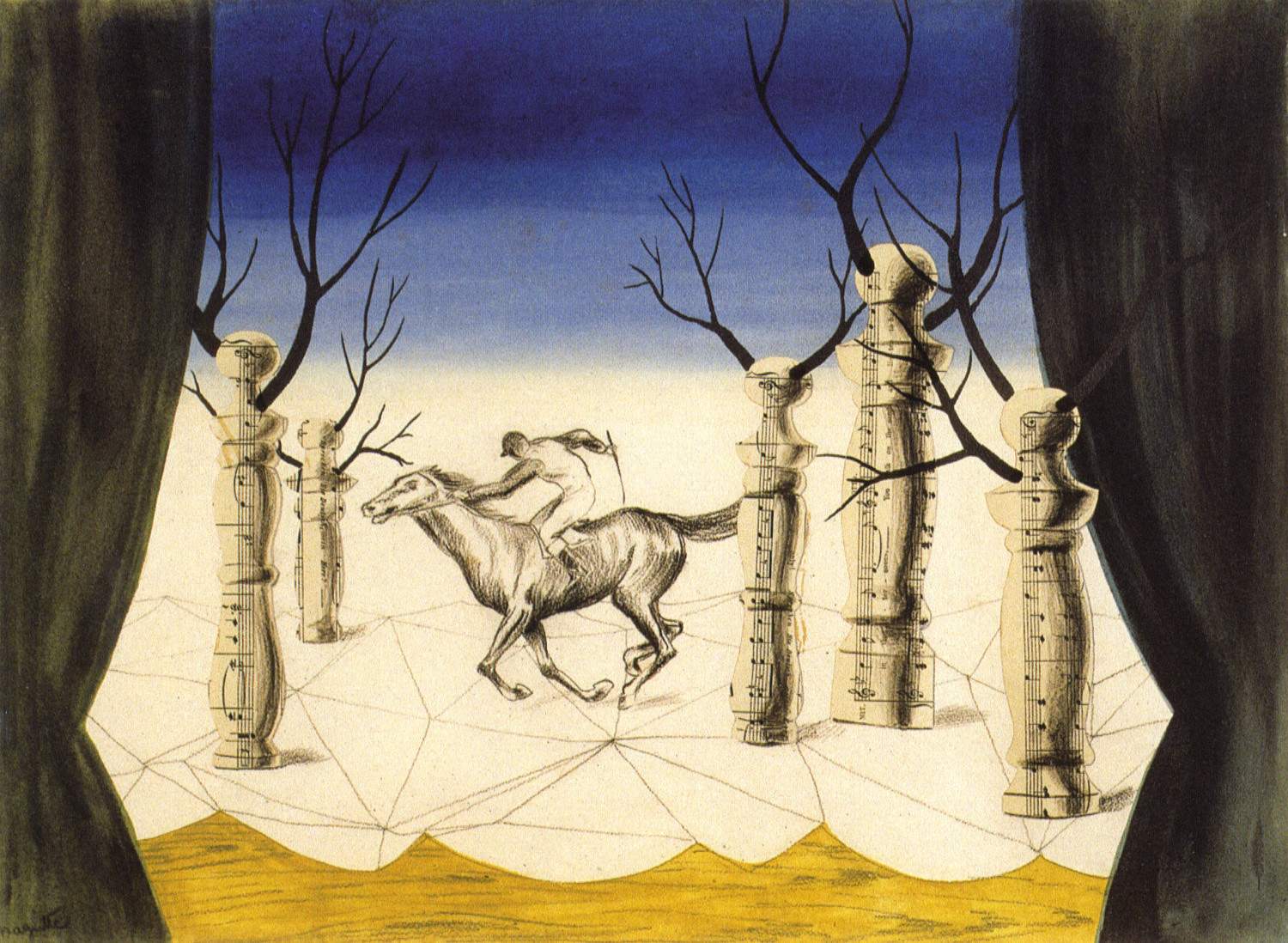

Parallel to his work as a graphic designer, Magritte continued his interest in the avant-garde, thus deciding in 1925 to join the Surrealist group in Brussels. His interest in the movement came with his discovery of Giorgio de Chirico’s painting Song of Love , whose ability to represent a new way of seeing, going beyond appearances, he admired. The first Surrealist picture he painted was Le Jockey Perdu (1926), a watercolor collage in which a jockey is depicted on top of his own galloping horse running toward trees in the shape of chess pieces: the entire scene is surrounded by a curtain that goes to accentuate a scenic vision.

A year after joining the Surrealist Avant-Garde, Matisse met André Breton, a leading figure in the Movement. In 1927 he held his first solo exhibition at the Le Centaure gallery in Brussels: the show turned out to be a total failure, and all sixty-one works exhibited were heavily panned by critics. The following year, in 1928, he and his wife Georgette decided to move to Paris. Their move to Paris was short-lived: the gallery La Cantaure where the painter had a work contract closed, and the two decided to move back to Brussels in 1930 to a neighborhood north of the city at 135 rue Esseghem in Jette. Their quarters would become a meeting place and landmark of the Belgian Surrealist Movement. Since 1999 the same apartment has been used as a house-museum in memory of the celebrated artist.

With the advent of World War II, René Magritte decided to move again with his wife to the south of France to Carcassone to escape Nazi domination. This historical period would greatly influence his painting style: at first he would experiment with a new style called “à la Renoir” or “solar,” moving from stark painting and correct drawing to painting with lighter themes and brighter colors. The solar period will end in 1947, giving way to a new period called “cows,” where the painter will take the concepts of the previous period to exasperation, painting provocative works full of rebellion by poking fun at Fauvism.

The painter would achieve fame only in the 1960s, a few years before his death. Thanks to the advent of pop culture and the exhibition dedicated to him at the Museum or Modern Art in New York

in 1965 his paintings achieved notoriety. René Magritte died on August 15, 1967 at his home on rue des Mimomas in Brussels from pancreatic cancer.

|

| René Magritte, La trahison des images (1928-1929; oil on canvas, 63.5 x 93.98 cm; Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art) |

|

| René Magritte, Le Jockey perdu (1926; collage, watercolor, pencil and ink on paper; New York, Museum of Modern Art) |

Although belonging to the Surrealist movement, characteristic elements can be found in Magritte’s painting that highlight its uniqueness: his way of painting is also called “pictorial illusionism” in that it depicts a classical, ordinary, two-dimensional reality by playing more on concept than painting. He transforms the real into the surreal while leaving plenty of room for the viewer’s imagination. During unhappy years in the postwar period he experimented with other painting techniques “in the manner of Renoir,” a style that exudes lightness by setting aside the paranoia and questioning of earlier years: the palette thus became richer with bright, vivid colors, abandoning gloom. This period, however, was only a medium, thus leaving room in 1947 for his “vache” (cow) period in which in a satirical and ironic key he critically reworks the thoughts and representations of the French Fauves. The two experimental periods were short-lived and soon after Magritte returned to painting in his usual manner.

In the 1928 painting The Lovers , Magritte depicts two figures in the foreground with their faces covered by a white veil, probably in memory of their mother who died by suicide and was found in the Sambre River with a shirt wrapped around her face. The white veil prevents the two lovers depicted from kissing and communicating with each other, making them unrecognizable. The atmosphere that the painting communicates is one of poignancy: the skillful choice of color, as in the case of the female figure’s red dress that resembles death, underscores the painting’s restlessness. The painting certainly refers to Giorgio de Chirico’s famous painting Hector and Andromache (1931) in which Hector and Andromache are depicted in the form of a mannequin in the moment of greeting just before the duel against Achilles. The analogy is visible on both a formal and conceptual level, as the impossibility of loving each other is also perceptible in the latter canvas (“There is an interest in what is hidden and what the visible does not show us,” the artist himself explains. “This interest can take the form of a decidedly intense feeling, a kind of conflict, I would say, between the hidden visible and the apparent visible.”).

Among Magritte’s most famous works is Golconda from 1953: the title evokes the city of the same name in India that has entered the collective imagination thanks to its contrast between the city’s immense wealth and the poverty of its citizens. As in all of Magritte’s works, the latter proposes a critical vision that leaves the viewer room to question his or her own interpretation. The work depicts a series of men in a static pose in the air in typical bourgeois attire (jacket, tie, bowler hat) that we can also find in other famous paintings such as The Son of Man (1964) or in

Mr. and Mrs. Wilbur Ross (1966 ) thus differing only by the different facial expressions. In the background sprout roofs of typical Belgian houses and a clear sky that occupies most of the scene. The multiplicity of men in the scene suggests on the artist’s part a critical look at homogenization. Although the clear sky communicates a sense of tranquility the quantity of men present stands in complete contrast generating a disturbing feeling.

In La Trahison des Images (1926-1966), Magritte presents a depiction of a pipe, depicted in a sharp and precise manner, with attention to detail. This figure is accompanied by a caption quoting “ceci n’est paso une pipe” (“this is not a pipe”). Once again Magritte places emphasis on the language he uses. He will later state, “Who would dare claim that the image of a pipe is a pipe? Who could smoke the pipe in my painting? No one. Therefore, it is not a pipe.” The artist thus takes an ironic attitude that seeks above all to pose questions in the mind of the viewer of the work. As Magritte states, what we see on the canvas is only a representation, and as such the object represented cannot fulfill its primary function, which is to be smoked and used. With this work Magritte opens a debate between real object and representation that still raises questions today by proving to be contemporary. Some artists will question the same juxtaposition: Joseph Kosuth, for example, in Una e Tre Sedie (One and Three Chairs ) places the same focus on language by reproducing a photo of a chair, a real and usable chair, next to it, and the dictionary definition of chair questioning the concept of a chair. La Trahison des Images is also important because it consecrates Magritte as a precursor of conceptual art.

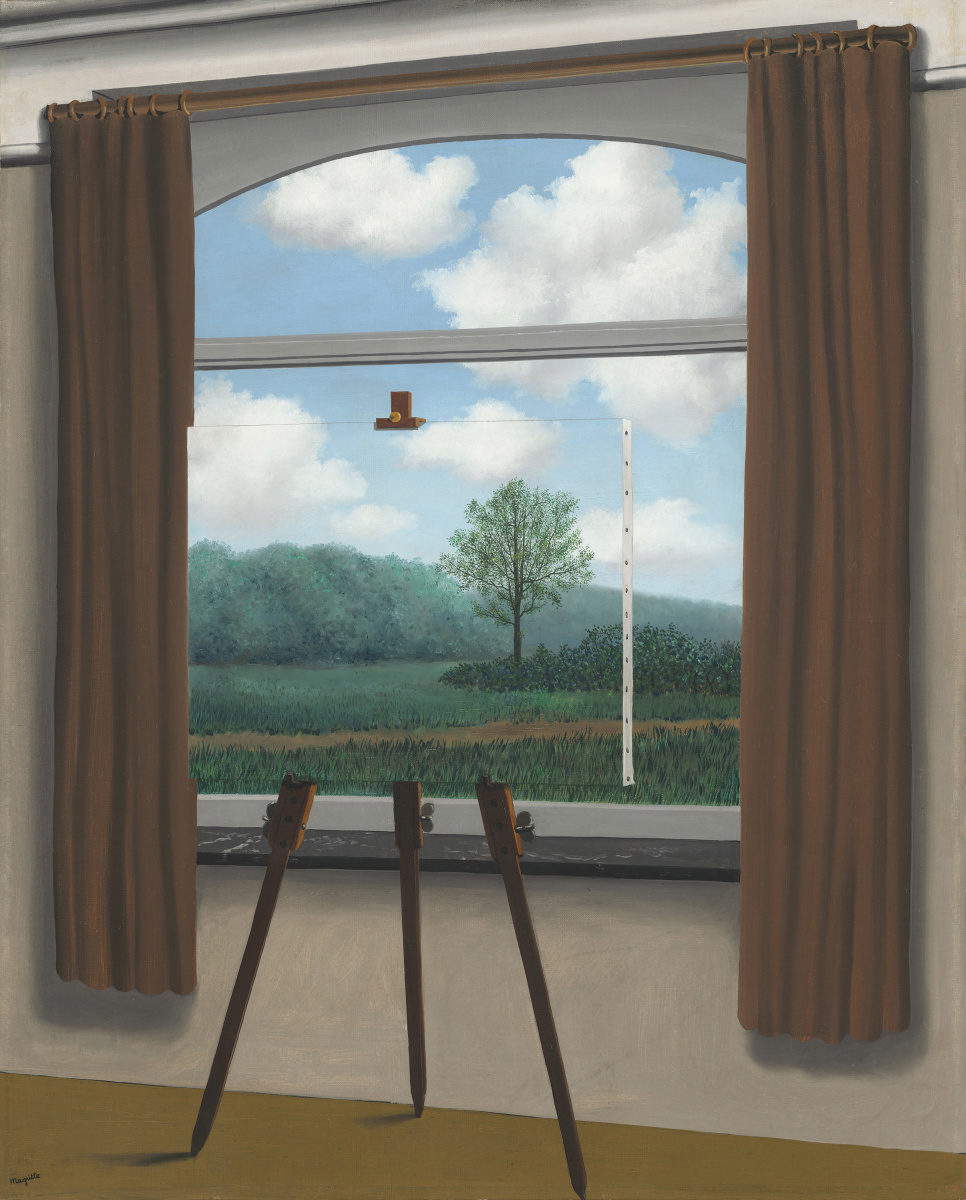

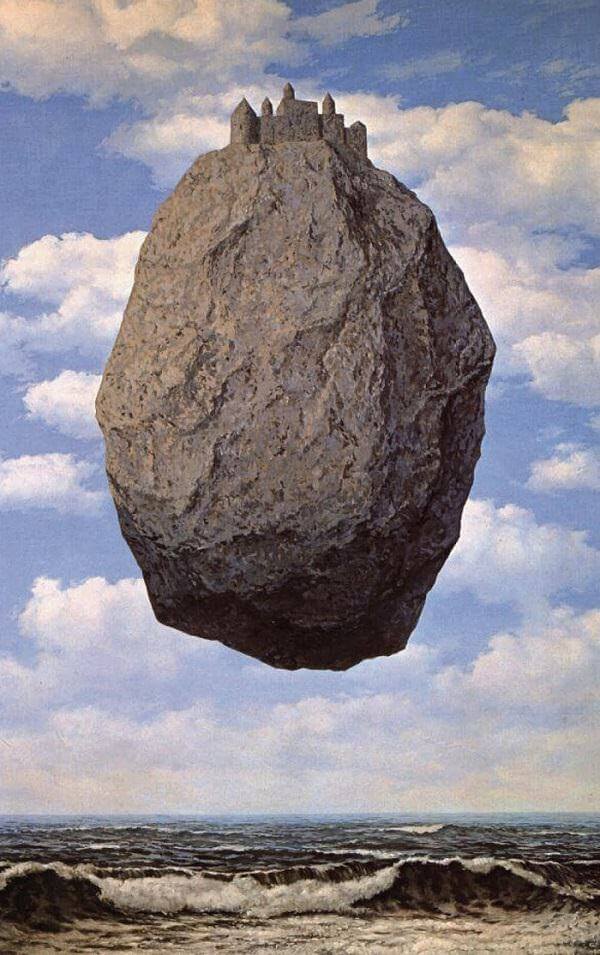

Again, The Human Condition II (1935) is the second version of the painting of the same name: both belong to the “when in the painting” series. In this painting, as in the first version, there is an easel on which rests a canvas representing a landscape, the same that constitutes the background landscape merging with each other giving a perception of continuity. The first version of the painting depicts a typical country landscape while the second version depicts a typical seascape. Playing with juxtapositions and optical effects, Magritte again investigates as in the case of La Trahison des Images the relationship between representation and reality, questioning what really is. When the work was completed, the painter would write, “I placed in front of a window, seen from inside a room, a painting that represented exactly the part of the landscape hidden from view in the painting. So the tree represented in the painting hid from view the real tree behind it, outside the room. It existed for the viewer, as it were, simultaneously in his mind, as inside the room in the painting, and outside in the real landscape. And that is how we see the world: we see it as outside of us even though it is only of a mental representation of it that we experience within ourselves.” Magritte’s research continued along the same lines in his later career, as evidenced by the 1959 work The Pyrenees Castle , a work commissioned by lawyer Harry Torczyner, who chose the painting’s subject. The image depicts a large rock on top of which sits a castle: the large boulder is represented suspended in the air, as if set in weightlessness, in which the background is provided by a seascape that accentuates the contrast between lightness and heaviness. The hardness of the painting is also confirmed by the painter himself, who in a writing with the commissioner states, “it is not free from rigor, even hardness.” Everything appears suspended, not only the rock but also time.

|

| René Magritte, The Lovers (1928; oil on canvas, 54 x 73 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| René Magritte, Golconda (1953; oil on canvas, 81 x 100 cm; Houston, Menil Collection) |

|

| René Magritte, The Human Condition (1933; oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

|

| René Magritte, The Pyrenean Castle (1959; oil on canvas, 200 x 145 cm; Jerusalem, Israel Museum) |

To admire the master’s paintings and visit the places he frequented and lived, there is no better city than Brussels, the Belgian capital where the artist stayed for most of his life with his wife. The site visit.brussels/en/ suggests an itinerary entirely dedicated to the painter. The stops recommended by the site are: the Magritte Museum (which houses many of the artist’s works), La Fleur en Papier Doré (art café frequented by the Movement), Greenwich (historic café where Magritte played chess with his companions), the House-Museum (the artist’s famous home), Shaerbeek Cemetery (the place where Magritte rests). Most of the artist’s works are kept at the Magritte Museum in Place Royale in Brussels. Starting in 1984, the chief curator of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Belgium decided to dedicate a room to the painter, acquiring more and more works there was a need for more space and so in 2005 it was decided to establish a dedicated museum in Place Royale. It was later opened in 2009 and to date some 250 works by the master are on display.

The House-Museum at 135 Rue Esseghem in Brussels, as anticipated, was a key place during the life of the painter, his wife but also the entire group of Surrealists. After Georgette’s wife their possessions were sold at auction by Sotheby’s, it took time before we were able to reconstruct the dwelling as it was inhabited. Thanks to photographs and testimonies from people who lived in the house as it was, the furnishings were recreated from 1993 to 1999. The entire house-museum is considered a tribute to the painter.

There are many museums in the world that preserve works by René Magritte. In Italy, however, there are very few of his paintings. Magritte’s most famous “Italian” painting is probably The Voice of the Winds, a 1931 painting kept at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. Other works of his can be found at the Pinacoteca Civica in Savona (where La confidenza capitale is kept) and at Palazzo Maffei in Verona. In France, his works can be found at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which preserves one of his major masterpieces(The Secret Double), while several works are kept in American museums: the LACMA in Los Angeles preserves La trahison des images, several of his paintings are at the MoMA in New York, and still works by Magritte can be found at the National Gallery in Washington.

|

| René Magritte, life and works of the great quiet saboteur |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.