Relational Art: theory, origins, main artists

The expression “Relational Art” refers to a cultural movement, a contemporary art trend whose theorization is connected to the figure of French critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud (Niort, 1965). This art form, also known as “Socially Engaged Art,” “Community Based Art” and “Participatory Art,” developed around the mid-1990s.Relational work exists because it is based on the condition of the existence of relationships and ties: therefore, the presence of other people in the production of this art is necessary. Relational art does not merely create aesthetic objects, but focuses on creating human experiences and relationships, turning viewers into actors. Therefore, the active participation of the audience becomes necessary.

This artistic trend is contemporary in that it was also born with the intention of bearing witness to the time that accompanies it; in fact, it is an expression with marked political and social characteristics. Central to the relational artistic vision is the conception of man in terms of a creative animal: the relational artist is someone who abandons the production of typically aesthetic objects and devotes himself to creating devices capable of activating an instinct for creativity in the audience. The work of art sets aside the aesthetic aspect to become a site of dialogue and confrontation, and, therefore, of relationship. The relational work is not such as an artistic result or artifact, but is indicative because it is representative of a path, the manifesto of a process carried out between several parties, where an encounter and the gradual discovery of the other has taken place.

Among the precursors of relational art can be considered Maria Lai (Ulassai, 1919 - Cardedu, 2013) as well as the Piombino Group composed of Pino Modica (Civitavecchia, 1952), Stefano Fontana (Turin, 1967) and Salvatore Falci (Portoferraio, 1950) and, later, Cesare Pietroiusti (Rome, 1955). Instead, artists such as Henry Bond (London, 1966), Angela Bulloch (Rainy River, 1966), Maurizio Cattelan (Padua, 1960), Félix Gonzáles-Torres (Guàimaro, 1957 - Miami, 1996), Liam Gillick (Aylesbury, 1964), Jens Haaning (Copenhagen, 1965), Carsten Höller (Brussels, 1961), Pierre Huyghe (Paris, 1962), Philippe Parreno (Oran, 1964), Rirkrit Tiravanija (Buenos Aires, 1961), Xavier Veilhan (Paris, 1963).

Origins and aesthetics of relational art

The codification of this art movement is inextricably linked to the name of French theorist and exhibition curator Nicolas Bourriaud (Niort, 1965). The scholar’s activity was distinguished by his willingness to reconcile theoretical and curatorial aspects. Bourriaud was credited with formulating theories from his frequentation of more experimental artists. Among his publications, Esthétique relationnelle (1998) Formes de vie has had considerable resonance . Other writings include L’art moderne et l’invention de soi (1999), Postproduction (2002) and Radicant. Pour une esthétique de la globalisation (2009).

The writer began his work as an art critic in the second half of the 1980s and organized many significant exhibitions: notably Traffic (1996) at the CAPC Musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, Touch. Relational art from the 1990s to now (2002) at the San Francisco Art Institute and an important curatorial activity at the Palais de Tokyo (2000 to 2006). Through his experience, Bourriaud contributed to the definition of relational art, and through the direct and personal collaboration the theorist had with artists, he was able to point out what particular characters their works had in common, without, however, identifying a univocal style. Rather, Bourriaud understood that relational art was above all a common and certainly new theoretical horizon compared to the past.

In the scenario of the contemporary world, characterized by mass communication, progressive globalization and homogenization of the type of interpersonal and economic relationships, the relational artwork takes on the function of an interstice, that is, a space in which possible life alternatives are created.

The French theorist observed with a critical eye the practices and processes of numerous contemporary artists, pointing out the activity of some artists, defined by him as sign operators or semi-naïve (in particular he mentioned the work of Félix Gonzáles-Torres, Philippe Parreno, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Liam Gillick and Carsten Höller). In Italy, the first examples of relational art are found in the 1980s. Sardinian artist Maria Lai in 1981 performed an extraordinary performance entitled Binding to the Mountain, which required the participation of the inhabitants of an entire village, that of Ulassai in Sardinia. Then in 1984 the collective Gruppo di Piombino was formed: under the aegis of the theorist Domenico Nardone, artists Pino Modica, Stefano Fontana, Salvatore Falci, and Cesare Pietroiusti came together. The group was active until 1991 and was born in opposition to the art forms of the Italian Transavanguardia and Anacronismo, and to all those art forms prevailing in Italy that tended toward the citationist recovery of traditional tools and materials. Despite its name, the group was mostly active between Rome and Milan and with its research contributed to the formation of relational art.

In the context of the relational movement, art was perceived as an activity to be shared. In Italy, art critic Roberto Pinto contributed to the effective affirmation and theorization of relational art with an exhibition organized in 1993, entitled Forms of Relationship. With this exhibition, the concept of relationship became part of investigations and researches that thickened around the Oreste Project: several critics, artists, intellectuals and literary figures came together and chose to work together for the creation of ideas to be shared in spaces, informal meetings and convivial gatherings.

Relational art is first and foremost sharing and therefore participatory. Other realities followed, such as the collective “Stalker,” formed by artists and architects, which was born in 1995. Stalker aimed to carry out territorial activities in a given space through exploration and relationship. For example, the action The Present Territories sees the collective engaged in a walk of five consecutive days in the city of Rome, along what is called its “dark side.”

Compared to traditional art, relational art was designed to be enjoyed in a specific hic et nunc. At a precise moment, for an audience called and invited specifically for fruition. In these precise coordinates, the artist takes action to orchestrate a process of intellectual exchange and physical participation, activating the creativity of visitors and protagonists.

Exponents of Relational Art.

In Italy, artist Maria Lai performed Legarsi alla montagna in 1981: the community of Ulassai, in the province of Nuoro, participated in a unique three-day event. The operation started on a significant day, September 8. The protagonist was essentially a 27-kilometer-long blue ribbon that was hooked between the doors, windows and terraces of the village’s houses. With this ribbon, Maria Lai made art a tool to redesign relationships, represented social cohesions by triggering a cultural reflection aimed at enriching the human and territorial fabric of the town community. It was a celebration, at the end of which some experienced climbers tied the ribbon to Mount Gedili, the highest in the town. Unfortunately, silence fell on this operation for more than two decades. Only recently has an awareness matured whereby Maria Lai is given credit for having carried out, on that day of September 8, the first relational art operation, with traits akin to the sphere of land art.

In the relational art milieu also operated the Piombino Group with interaction actions carried out in urban contexts. In their departure from the dominant contemporary art forms in Italy, the group proposed ideas and concepts far from the tendencies to make aesthetic artifacts with the use and recovery of traditional techniques, something that was happening punctually in the Italian cultural scene of the 1980s. The group’s work began in late 1984, when Falci, Fontana and Pino Modica exhibited Sosta Quindici Minuti, signing collectively. The work consists of five chairs first placed in the Giardini at the 1984 Venice Biennale.

In 1992, in Rome Pino Modica created the work Purchase Reservation Voucher, financing six vouchers worth 250,000 lire each. The vouchers were distributed to non-EU citizens through a lottery held at the CGIL premises. The immigrants could spend them at any city business of their choice; then the artist presented six platforms in the Alice Gallery, on each of which the goods chosen by the six buyers were displayed. It was an operation by which the artist aimed to alter the perceptual model that a merchant usually has of the immigrant, now not a questor but a buyer: in doing so, he explored the process of determining the object by tying it strongly to the issue of immigration. In this sense theaspect of political activism that Relational Art claims emerges very much. In 1995 the Stalker collective was formed in Rome: this proceeded to the investigation and formation of a knowledge of the territory through some group activities. The spaces deputed to the interest of the research were mostly fringe realities, abandoned territories. Stalker intervened in these spaces in an experimental sense, basing its modes of expression on exploratory, listening, relational and convivial environment practices. The design is collaborative and the environment is investigated together with the inhabitants, with the imaginaries and archives of memory. These knowledge tools aim to encourage the evolution and development of processes through the weaving of social and environmental relationships precisely where they have been lacking. Indeed, such absence of relationships and interactions is evidenced by the state of abandonment and degradation of the environments concerned. The present territories, this is the title, was one of the first actions of the collective, during which the group walked sixty kilometers in the city of Rome for five consecutive days, walking “the dark side of the city.”

Abroad, the voice of Nicolas Bourriaud had defined the lineaments of Relational Art in Relational Aesthetics (1998). This is not a work of art, but it is a publication that defined relational aesthetics, influencing many artists in creating works that promotedsocial interaction. The theorist noted here the names of great interest involved in this field, those of the so-called semionouts.

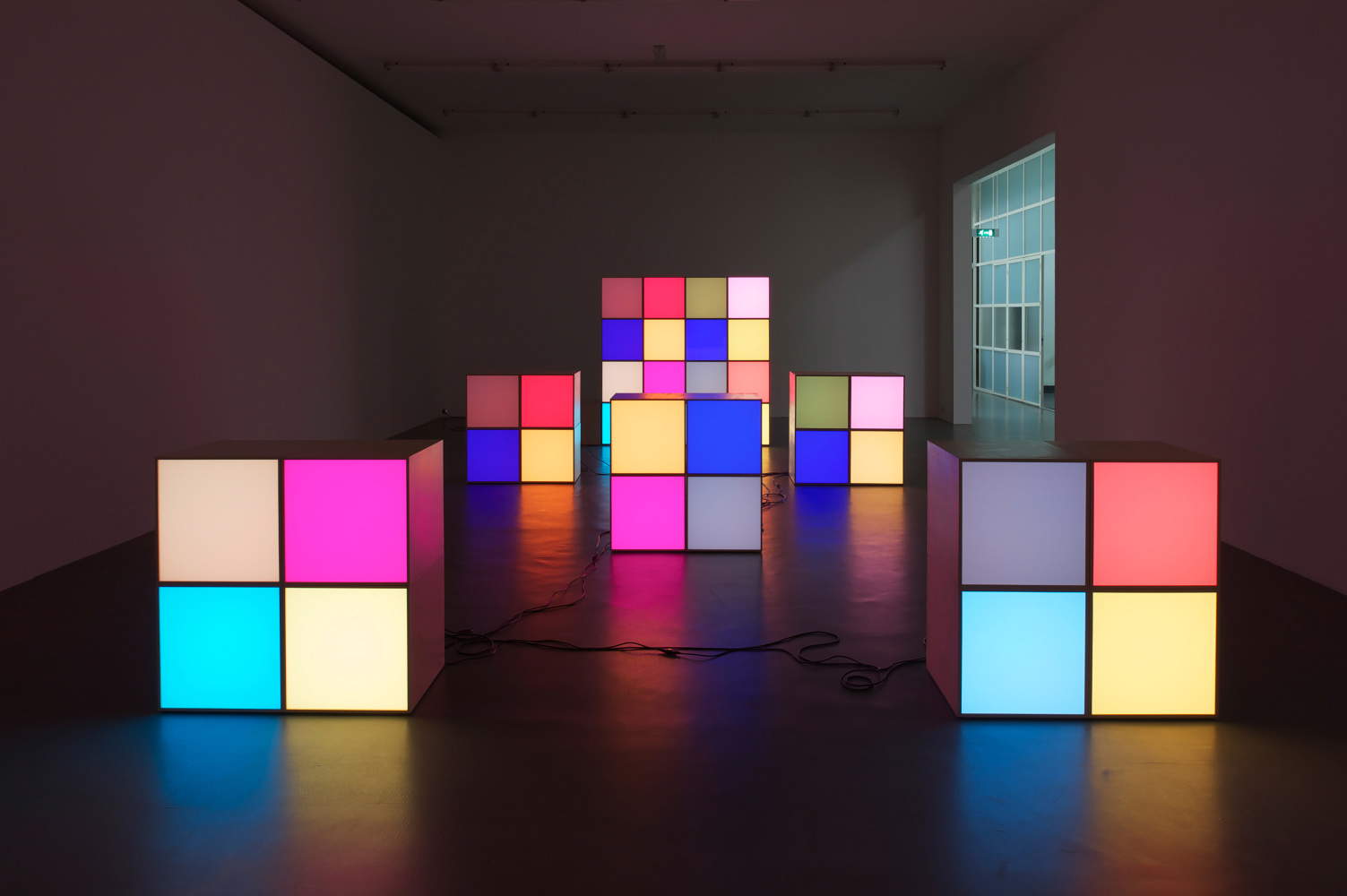

Rirkrit Tiravanija, for example, made Untitled (Free) in 1992: in an art gallery, the artist transformed the room into a kitchen where he invited some visitors. She cooked and served Thai food for everyone, free of charge, creating a serene environment of sharing and dialogue. Also in the early 1990s emerged British artist Angela Bulloch, who fits into the context of relational art through works that directly engage the public and explore the concept of interaction and participation. Her installations are not simply objects to be passively observed, but tools through which the viewer is called upon to interact, modify or complete the work. An emblematic example are the Pixel Boxes, one of his most famous works. These installations consist of light modules that illuminate based on certain interactions. Pixel Boxes are not just light sculptures, but devices that respond to external stimuli, such as human presence or sound, thus creating a dialogue between the work and the viewer. In this way, Bulloch makes clear how the artwork can be a platform for building relationships, both physical and conceptual.

The art of Félix González-Torres was also defined as relational. The artist routinely used rows of intertwined lights, sheets of paper, billboards, clocks, piles of colored candy, the artist, without qualms or modesty, invited the public to enter his life and take part in it, even if only for a very short time. This is why her art is relational: the presence of her lover Ross Laycock and the love González-Torres felt for him can be felt in the almost manic recurrence of the number two: in Untitled (perfect lovers), an installation proposed several times between 1987 and 1990, two clocks, with their perfectly synchronized progression, symbolize the bond that transcends the objects themselves, even beyond death, in a perpetual, unison movement. Particularly illustrative is Untitled (Para Un Hombre En Uniform), a work composed a pile of wrapped candies, spread out on the gallery floor. The candies, which can be taken by visitors, represent the body weight of Ross Laycock, the artist’s companion, who was progressively reduced due to the AIDS that affected him. The candies are arranged in an orderly and uniform manner, recalling the idea of military order and discipline, as suggested by the title, which refers to “a man in uniform.” A key aspect of González-Torres’ work is precisely the interaction with the audience. In the case of Untitled (Para Un Hombre En Uniform), visitors are invited to take a candy, symbolizing participation in the artist’s memory and grief. This gesture creates an intimate connection between the work, the artist and the audience, and at the same time leads to the gradual dissolution of the work itself, reflecting the inevitable loss and impermanence of life.

As Pino Modica did in 1992, the issue of integration of ethnic minorities in social contexts by dominant capitalism was also addressed abroad. Danish relational artist Jens Haaning first made Turkish Jokes in 1994: by means of a loudspeaker installed in a square in Copenhagen, a series of Turkish-language stories were broadcast. The performance was also repeated in other cities such as Oslo, Berlin and Moscow.

Bourriaud observed that the dissemination of the stories and the resulting understanding by the ethnic minority group resulted in social inclusion. Moreover, since the stories were playful in nature, those aroused laughter that enabled the visualization of the network of relationships formed between people, connected and infected by their own smiles. This formation of network and relationships removed the migrant from the isolation of his or her foreign status. Jens Haaning used laughter as a relational and universal tool of language.

Another name highlighted by Bourriaud is that of Carsten Höller. In 2006, the Belgian artist created Test Site, which consisted of an installation in the rooms of London’s Tate Modern. The relational work was composed of large slides and visitors invited to interact by playing with the work, stepping out of the passive observation zone to actively participate (an operation later replicated in Florence, at Palazzo Strozzi, in 2018 with The Florence Experiment).

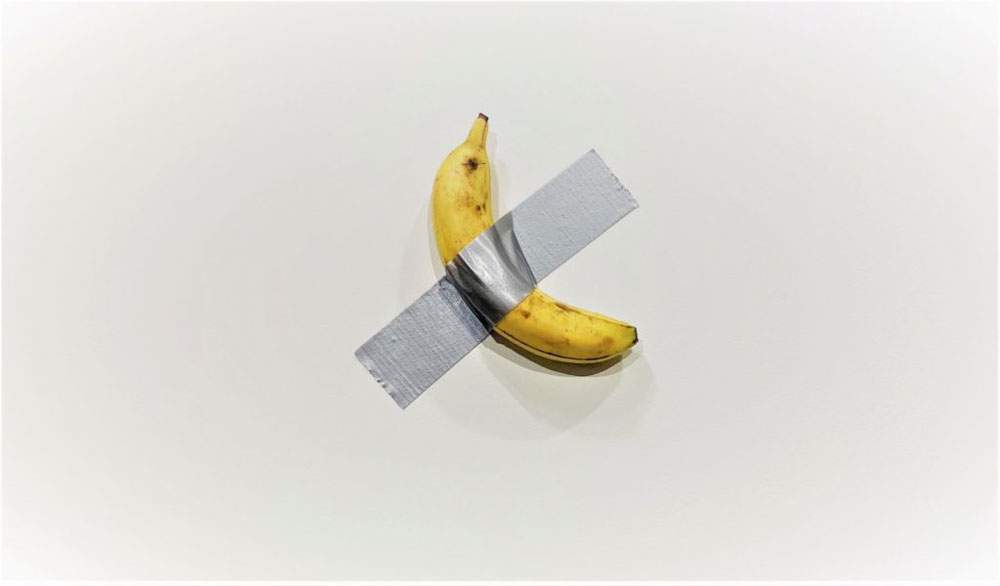

Also associated with the relational art movement is Maurizio Cattelan from Padua, who has never explicitly defined himself as a relational artist, but many of his works reflect the principles of this movement. His installations, performances and sculptures often create situations that invite the public to reflect, react and interact with the work in unexpected ways, and they often tend to create controversies in which the public, even of non-experts, participates through the press or social networks, thus triggering participatory processes that do not even presuppose direct, live viewing of the work. One example is Comedian, from 2019: this famous work, which consists of a banana taped to the wall, is a perfect example of how Cattelan uses irony to provoke discussion. The work is less about the physical object and more about the reaction it provokes in the public and the media. The banana, a mundane object, is transformed into a work of art by the context and social dynamics it creates, reflecting the relational idea of art as a means of generating dialogue. The work conceptually follows A Perfect Day (1999): In this installation, Cattelan literally taped his gallery owner Massimo De Carlo to a wall. The work plays on the concept of power and control in the relationship between artist and gallerist, but it is also a provocation that requires the audience to reflect on power dynamics in the art world. The interaction here is not only between the work and the audience, but also between the artist and his collaborator, making the work a multi-layered dialogue. Or take America, from 2017, as an example: this sculpture, a toilet made entirely of solid gold and fully functional, was exhibited at the Guggenheim in New York, where visitors could actually use it. The work not only challenges the concept of luxury and wealth, but also creates a direct and intimate interaction with the audience, making the experience of art something personal and physical.

Again, Frenchman Pierre Huyghe is known for his complex and immersive installations, which often combine visual, sonic, performative and living elements. His works explore the nature of perception and participation, challenging the boundaries between reality and fiction, natural and artificial, human and nonhuman. Particularly significant in this sense is the Zoodram series, which employ living creatures (aquariums with fish and crustaceans as well as plants) to explore their behavior and interactions, obviously also in front of an audience: these works are like reproductions of social phenomena. Also relevant in France is the work of Xavier Veilhan, whose works often seek to engage the audience directly, encouraging interaction and active participation. This approach manifests itself both in the creation of public spaces that invite collective contemplation and in the use of materials and forms that stimulate a dialogue between the work and the viewer. His work Studio Venezia (2017) is famous: made for the French pavilion at the Venice Biennale, this installation represents a real music recording studio, where artists from around the world were invited to perform during the event. The work not only explores the interaction between visual art and music, but also creates a place for cultural exchange and creative collaboration, embodying the principles of relational art.

|

| Relational Art: theory, origins, main artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.