The great French painter Eugène Delacroix had to write that Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520) was “the earthly manifestation of a soul that speaks to the gods.” Many other artists have defined the Urbino in these terms, describing him as a kind of god on earth: for example, Giorgio Vasari stated that those who possess gifts similar to Raphael’s are “mortal gods,” and various authors and theorists, such as Bellori, Malvasia, Milizia, Quatremère de Quincy and so many others believed that Raphael was an absolute model of perfection. Raphael is one of the greatest protagonists in the history of art because no one like him was able to combine in such a balanced and harmonious way the ideal beauty, the purity of the figures depicted, a pronounced sense of space that resulted in seemingly simple but in reality very studied and articulate compositions, the gentleness and tranquility of attitudes. Raphael’s is a complex and easy art at the same time: “his painting,” said art historian Marzia Faietti, “ is so meditated, pondered, sublimated, it contains so many and layered levels of reading that every observer, from the simplest to the most cultured, has the possibility to admire it and admire different aspects and qualities. Raphael is an artist for everyone.”

Raphael was an extraordinarily receptive artist: open to many stimuli, he studiedancient art but also looked with passion at the works of his contemporaries, above all Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti, thanks to whom his language could be further enriched, updated and updated in turn. Raphael’s works were points of reference for the renewal of portraiture, for the altarpiece, and also for the representation of the traditional themes of humanistic culture: in the Stanza della Segnatura, for example, the great artist from the Marche region was able to bring to life the programmatic contents of Pope Julius II with images that were able to express meaning in a clear and engaging way, making Christian revelation and ancient wisdom dialogue with extraordinary harmony.

Finally, Raphael can be considered the painter of ideal beauty, a model not only for his direct pupils, but for all the classicist painters of the seventeenth century, such as Guido Reni or Domenichino, all the way to the neoclassicism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (think of Anton Raphael Mengs), to the nineteenth century (Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Théodore Gericault among others), and even to contemporary art. Again, Rome owes part of its beauty to Raphael: not only because, according to Pietro Aretino, Pope Leo X was “the inventor of the greatness of the popes” thanks to the works that Raphael carried out under his pontificate, but also because if today we can admire a good part of the wonders of ancient Rome, we owe it to Raphael, whom we can almost consider the first superintendent in history. In 1515, in fact, Leo X invested him with the role of prefect of all the marbles and tombstones, and the artist set about compiling a catalog of the antiquities to be preserved: we can infer all his passion for antiquity in a famous letter sent to the pontiff, which has become almost a basis for the modern concept of protection. Many, then, are the souls of the art of Raphael, one of the greatest artists of all time.

|

| Raphael, Self-Portrait (1506-1508; oil on poplar panel; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings). Photographic Cabinet of the Uffizi Galleries - On concession of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism. |

|

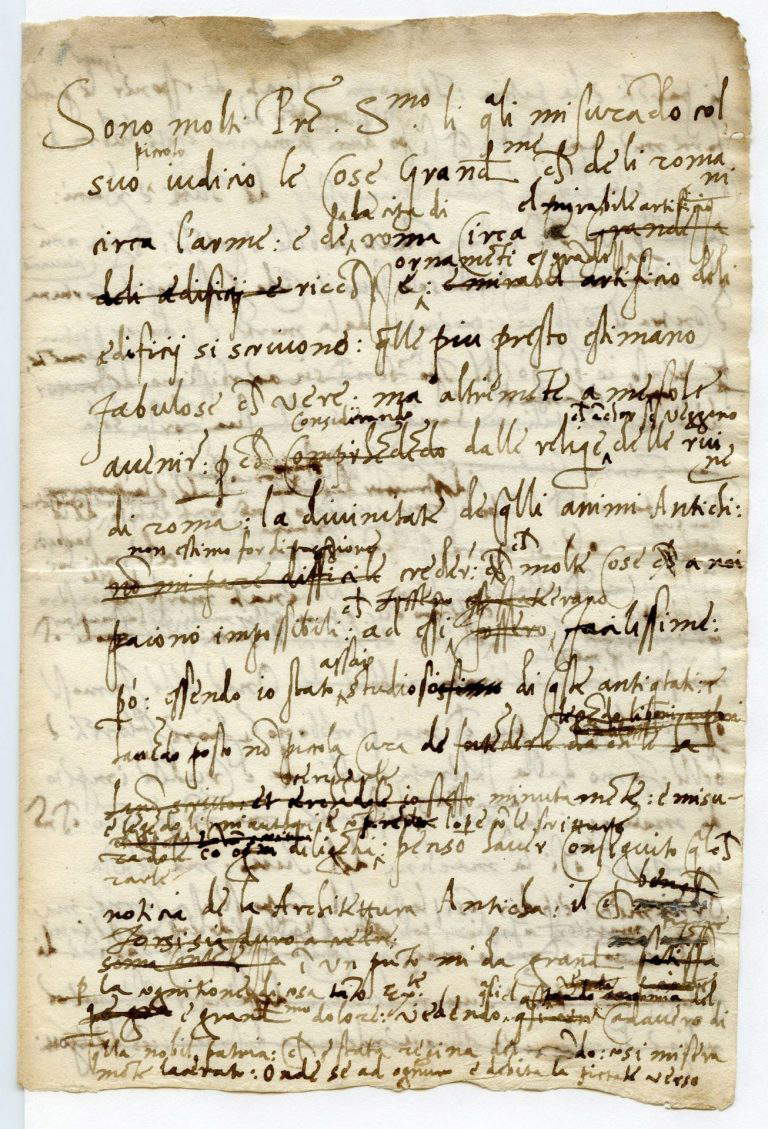

| Raphael and Baldassarre Castiglione, Letter to Pope Leo X (s.d. [1519], paper manuscript, 6 papers, about 220 x 290 mm each; Mantua, State Archives) |

Raphael Sanzio was born in Urbino on March 28. His father was Giovanni Santi, one of the Montefeltro court painters (“Sanzio” is a vulgarization of the Latin “Sancti”), and his mother was Magia di Battista Ciarla, who died when the artist was only eight years old. Raphael completed his first apprenticeship in his father’s workshop in the 1490s, in Urbino, where he was able to make repeated visits to the Ducal Palace and where he could therefore see the works of Piero della Francesca, Melozzo da Forli, Antonio del Pollaiolo, Pedro Berruguete, Giusto di Gand, Luciano Laurana, Francesco di Giorgio Martini and other important artists active in the Feltresque court. Giovanni Santi died in 1494, and Raphael subsequently became a pupil of Perugino, although we do not know exactly when the two met. In 1499, at the age of sixteen, the artist moved to Città di Castello, where he obtained his first independent commission: the Stendardo della Trinità, which brought him into the limelight in local circles, so much so that, in 1500, he was commissioned by the nuns of the monastery of Sant’Agostino to paint the Pala di san Nicola da Tolentino, which the artist executed in Evangelista da Pian di Meleto. In the same period, between 1501 and 1502, Raphael made trips to Florence and Siena, where he was invited, according to Giorgio Vasari, by Pinturicchio. One of his greatest masterpieces dates from 1504: the Marriage of the Virgin desinated at the church of San Francesco in Città di Castello. Later that same year, the artist moved to Florence, where he stayed until 1508.

In Florence, Raphael painted some of his best-known masterpieces, such as the Madonna of the Goldfinch(read an interesting article on this work and how it came into being), the Canigiani Holy Family, the Madonna of the Belvedere, the Madonna Tempi, the Bridgewater Madonna, and the portraits of the husband and wife Agnolo and Maddalena Doni. The artist worked almost exclusively for private patrons and in the meantime continued to maintain relations with Umbria: in 1505, for example, he painted the Trinity with Saints in the church of the monastery of San Severo in Perugia, a work left unfinished and then finished several years later by Perugino. In addition, in 1507, and again for Perugia, he painted while working in Florence one of his best-known masterpieces, the Baglioni Deposition, for the church of San Francesco al Prato, now in the Galleria Borghese(read a detailed discussion of this important work). The Florentine period ended with a masterpiece destined to influence many painters: the Madonna del Baldacchino, which the artist left unfinished.

In 1508, Raphael moved to Rome, where Pope Julius II commissioned him to paint the fresco decoration of the Stanza della Segnatura: here the artist painted some of his most famous masterpieces, above all the School of Athens, and the appreciation was such that he was entrusted with the decoration of other rooms (the Stanza di Eliodoro and the Sala dell’Incendio di Borgo, while he would make for the Sala di Costantino the cartoons for the decoration that his pupils would execute after his death, between 1520 and 1524). It was in 1512 that he made the Madonna di Foligno, with which the artist renewed the tradition of the altarpiece (and he would do the same in 1513-1514 with the Sistine Madonna, which became very famous especially for the little angels in the foreground, one of the most iconic images in the entire history of art), and in 1514 the artist became superintendent of the fabbrica of St. Peter’s, succeeding his countryman Donato Bramante after having been his collaborator. In the same year, the new pope, Leo X, commissioned him to make cartoons for the celebrated tapestries preserved today in the Vatican Museums. In 1516 he began work on the Transfiguration, his last masterpiece, which he would finish in the last year of his life. The artist died in Rome on April 17, 1520.

|

| Raphael, Madonna of the Goldfinch (1506; oil on panel, 107 x 77 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Raphael, Portraits of the Doni couple, left Agnolo (c. 1506; oil on panel, 65 x 45 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery), right Maddalena Strozzi (c. 1506; oil on panel, 63 x 45 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Raphael, Borghese Deposition (1505-1507; oil on panel, 174.5 x 178.5; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

There are many themes that could be introduced by delving into Raphael’s art, starting with the elements he was able to infer from the artists with whom he came into contact, either directly or indirectly. With the fragments of the Pala di San Niccolò da Tolentino (the Madonna with the Eternal preserved at the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples, the angel preserved at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia, and the angel in the Louvre) we can appreciate his links with the Tuscan and Umbrian models within which he was trained, as well as his connection with Melozzo da Forlì, a painter from whom Raphael may have inferred the sense of delicacy and serenity discernible especially in the Brescia angel (Melozzo da Forlì was an artist capable of grafting lyricism and sweetness onto the solemn, perspective-impeccable compositions derived from Andrea Mantegna ’s study of Piero della Francesca: the Forlivese was probably the first painter to propose a new canon of beauty based on grace, a human and gentle beauty). With the St. Sebastian of the Carrara Academy in Bergamo, on the other hand, Raphael’s relationship with the elegance typical of Perugino’s art can be deepened: the young Raphael is an artist who is working out a new autonomous and original language.

He would get there very early, already in Florence, particularly with his Madonnas, which for centuries represented the canon of ideal beauty, the highest feminine perfection, from which so many artists were inspired. His Madonnas express not only a sense of devotion, but great humanity, for Raphael’s Madonnas, though caught in their ideal beauty that served as a model for centuries, emanate a strong human warmth that we notice in their poses, looks, and attitudes. And, speaking of innovative inventions, it is impossible not to mention the Madonna del Baldacchino, painted in 1508 and left unfinished because in that year the artist had to leave for Rome (the work is now in Florence, in the Pitti Palace): here Raphael introduces an original element, namely the very elegant canopy under which the Madonna and Child stand, a setting that would later be “imitated” by several other artists, such as Andrea del Sarto and Fra’ Bartolomeo. Raphael would later again revamp the formula of the altarpiece with the Madonna of Foligno of 1516: it is a painting that stands out for the delicacy of the Madonna and Child (despite the fact that their presence constitutes a theophany that moves somewhat away from the intimacy of the atmospheres of the Madonnas of the Florentine period, their figures nevertheless retain that oh-so-human aspect that characterized the Madonnas of the earlier period), for the naturalism of the characters (see the patron and St. John the Baptist), for the way the characters are inserted into the landscape, and for the unusual detail of the clouds that take on the appearance of cherubs: the Madonna of Foligno thus renews the theme of the sacred conversation in particular and the altarpiece in general.

In the Roman period, from 1509 to 1520, the longest phase of Raphael’s career, fundamental was his relationship with the ancient, at all levels. The subject is vast, but one could begin with the School of Athens: in the Vatican Rooms it is possible to appreciate a Raphael very different from that of the Florentine period, a Raphael who updated himself with contact with Michelangelo and with ancient art to elaborate a monumental and classical language. The School of Athens has been variously interpreted, but perhaps the most likely reading is the one that would have philosophy as the means to arrive at truth, according to a reading in a neo-Platonic key. The fact that philosophers are represented with the features of artists introduces an element in support of this thesis: art, as a way of expressing beauty, is able to lead human beings to the good and the true, according to the Neoplatonic idea for which beauty is the earthly manifestation of love and also of truth and knowledge we could. Moreover, in the Rome of popes, great humanists, intellectuals and letters, Raphael was also able to try his hand at architecture andarchaeology: the artist had the opportunity to participate in excavations that brought to light traces of classical antiquity, to learn about and preserve the finds of ancient Rome, and to perfect the study of his painting thanks to ancient models.

Finally, Raphael also laid the groundwork for what was to come after him. His powerful Transfiguration, his last work, is in fact a shining anticipation of Mannerism. The depiction is divided into two registers, the upper register in which we see the episode, with the three apostles dazzled by the divine appearance of Jesus with the prophets Moses and Elijah on either side, and the lower register populated with characters who refer to the episode immediately following in the Gospel, namely the healing of a possessed man, whom we see on the right being held by the man dressed in green, with the crowd showing him to the disciples as a surround. The scene at the top is symmetrical, heavenly, while at the bottom it is excited and tumultuous, and despite this diversity of atmosphere Raphael has managed to create a very balanced work, dense with Michelangeloesque hints but also with chromatic delicacy: the very palette of the Transfiguration will be a reference for many Mannerist painters. The Transfiguration is a typical example of the last Raphael, of the period in which the more intimate and delicate compositions give way to bold and animated scenes, though always subjected to careful formal control. It is a work that thus displays all the characteristics from Raphael’s art, from the chromatic delicacy to the harmony that distinguished the early part of his career (we notice it especially in the upper part), to the dynamism of the lower register that instead exemplifies the last Raphael. It is no coincidence that it was always a highly regarded work, and even, according to Vasari, it is the finest work that Raphael ever made.

|

| Raphael, Saint Sebastian (1501-1503; mixed media on panel, 45.1 x 36.5 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| Raphael Sanzio, School of Athens (1509-1510; fresco; Rome, Vatican City, Vatican Palaces, Stanza della Segnatura) |

|

| Raphael, Transfiguration (1518-1520; tempera grassa on panel, 410 x 279 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Pinacoteca Vaticana) |

Much of Raphael’s work is concentrated in Rome: in addition to the Vatican Rooms, there are his works at the Pinacoteca Vaticana, the Galleria Borghese, Palazzo Barberini (the world-famous Fornarina is found here), the Villa Farnesina (the splendid Galatea), and not to be forgotten are the frescoes in the Cesi Chapel in Santa Maria della Pace and the fresco of the prophet Isaiah in the church of Sant’Agostino (see also this article with five places in Rome in which to discover Raphael’s art). The other quintessential “Raphaelesque” city is Florence, where Raphael’s masterpieces can be found, meanwhile, at the Uffizi: the Madonna of the Goldfinch, the portraits of the Doni couple, the Perugino portrait, the portraits of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro and Elisabetta Gonzaga, the famous self-portrait, the portrait of Pope Julius II, and the portrait of Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici and Luigi de’ Rossi. At the Pitti Palace, on the other hand, one can admire the Madonna of the Chair, the Madonna of the Grand Duke, the Vision of Ezekiel, the Madonna of the Canopy, the portrait of Phaedra Inghirami, and the Veiled Madonna. Those in Urbino should not miss a visit to Casa Santi, where you can admire the painter’s first known work: the Madonna di Casa Santi, attributed to a Raphael around the age of 15. Also on the calendar, if you are in Urbino, is a visit to the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche to see the Muta. Again, in Perugia you can visit the Chapel of San Severo, which preserves the fresco with the Trinity, and seemingly in Umbria the Stendardo della Santissima Trinità is kept at the Pinacoteca Comunale in Città di Castello. In Bologna one of his masterpieces is kept at the Pinacoteca Nazionale: it is theEcstasy of Saint Cecilia. And then again works by Raphael can be found at the National Museum of Capodimonte in Naples, the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia, the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, and the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan (here the magnificent Marriage of the Virgin can be admired).

Raphael’s most famous works abroad include the Madonna Connestabile (at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg), the Madonna of Belvedere (at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in London) the Three Graces, the Madonna of Orleans and the Madonna of the Veil (all three at the Musée Condé in Chantilly), the Ansidei Altarpiece, the Madonna of the Carnations and the Madonna Aldobrandini (at the National Gallery in London), the Belle Jardinière and the portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione (at the Louvre), the Bridgewater Madonna and the Madonna del Passeggio (at the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh), the Sistine Madonna (at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden), the Madonna of the Fish, the Madonna of the Rose, the Spasimo of Sicily and the Visitation (at the Prado in Madrid), and the portrait of Bindo Altoviti (at the National Gallery in Washington).

|

| Raphael: life, works, masterpieces |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.