Postimpressionism defines the artistic trends that developed in France, with important influences in the rest of Europe as well, roughly between 1880 and the beginning of the twentieth century, which followed and, at the same time, surpassed the experience of Impressionism. Where the last official exhibition of the Impressionists took place in 1886, the activities of artists whose works ferried into the new century were manifested in not quite chronological succession. Most of the artists known as Post-Impressionists initially adhered to the Impressionist movement, only to turn later to an autonomous and gradually more ambitious and subjective style. The term, of English origin, conventionally denotes not an organized group with a programmatic manifesto, but rather the set of heterogeneous expressions of different painters, understood as evolutions of the Impressionist discovery of the decomposition of light and color. It was an artistic climate that involved artists of different interests and temperament who became absolute names in art history such as Paul Cézanne and Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, whose own orientations and masterpieces procured a far-reaching aesthetic impact that determined subsequent currents.

To the imitative depiction of subjects drawn from bourgeois life and nature, the post-impressionists each preferred personal experimentation with autonomous outcomes and different directions, nonetheless valuing that freedom from tradition and the dictates of academic art just earlier experimented with, and admitting debt to the colors of Impressionism and the technique of using them with short brushstrokes. As determined as they were to go beyond their predecessors, each painter pursued the uniqueness of their own quest toward a new definition of forms, not necessarily sharing stylistic goals with the others. They exhibited together on common occasions, but painted mainly alone in their own studios, unlike the Impressionists who had maintained as a close-knit group assiduous relationships by painting en plein air.Art historiography has grouped the various postimpressionist styles roughly into two currents: on the one hand a structured or geometric style that introduced cubism, and on the other a non-geometric expressiveness that led to abstract expressionism.

The term Postimpressionism has been in use since the first decade of the 1900s, coined for the work of French-area painters of the late 19th century byEnglish artist and art critic Roger Fry (London, 1866 - 1934). It was introduced, following the creation of the works in question, in a 1906 essay and then became the title of the first exhibition that decreed the arrival of some important representatives of Impressionism to a new artistic language.

Manet and the Post-Impressionists was the group show organized at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1910, also referred to as "the year of the Post-Impressionists," which featured paintings by Paul Cézanne (Aix-en-Provence, 1839 - 1906), Georges Seurat (Paris, 1859 - Gravelines, 1891), Paul Gauguin (Paris, 1848 - Hiva Oa, 1903) and Vincent Van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890), starting with the works of the father of Impressionism Édouard Manet (Paris, 1832 - 1883), a name at that time already known in England. Exhibition precisely on contemporary French painting that also involved Paul Signac, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Odilon Redon, Maurice Denis and Felix Vallotton, among others. All these French painters, apart from the Dutchman Van Gogh and the Spanish Picasso stationed in Paris, who scandalized the English art scene, which remained anchored in an art of imitation as opposed to the personalization and abstraction to which France and the rest of Europe were moving.

Manet considered as the first modern artist, not only because he had chosen subjects of his time but also because he had challenged traditional representational techniques, towed at that time the names, misrecognized in England, of those who were called the "four evangelists of Post-Impressionism," Cézanne, Seurat, Gauguin and Van Gogh, when by then the artists had already disappeared. Their group identity was thus posthumous, representative of the change in the autonomous approach to the work of art. Their common characteristics were the search for the solidity of the image as opposed to the floating painting of the Impressionists, the certainty and freedom of color. Despite the criticism the exhibition and the curator attracted, Roger Fry chose to reintroduce a Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912, supporting the international consideration the protagonists deserved and broadening the horizon with works by British and Russian artists. A signal of what had been a true stylistic demarcation.

After a phase of restless dissent among the Impressionists, just as Cézanne painted in isolation in Aix-en-Provence in southern France, Paul Gauguin in 1891 settled in self-imposed exile in Tahiti in French Polynesia, and Van Gogh painted in the countryside of Arles, leaving the nerve center of Paris. Seurat had died early at age 31, and his stylistic method was taken up and spread by Paul Signac (Paris, 1863 - 1935). There was indeed taking root among Western intellectuals, as a legacy of early 19th-century Romanticism, the need for renewed contact with authentic nature and a fascination with distant, less industrially developed cultures that were considered closer to spirituality and the elemental forces of the cosmos than the urban “artificial” centers of their European counterparts.

Cézanne, also known as the “Master of Aix” from the pleasant location to which he moved in the south of France, is considered a touchstone of late 19th century artistic quality and innovation. Abandoning the “impression” technique of evanescent light effects in 1878, his approach infused his subjects with a monumental permanence, and each element of the canvas was examined from multiple angles, whose material properties were recombined by the artist not as a copy, but as what he called “a harmony parallel to nature.” The painter tackled the fundamental question of spatial depth by seeking a synthesis in geometric forms, an early attempt to simplify objects and figures with a focus on defining volumes, which later inspired the Cubism of Georges Braque and Picasso in its early stage of development. Cézanne’s brushstrokes with separate colors set the school for many.

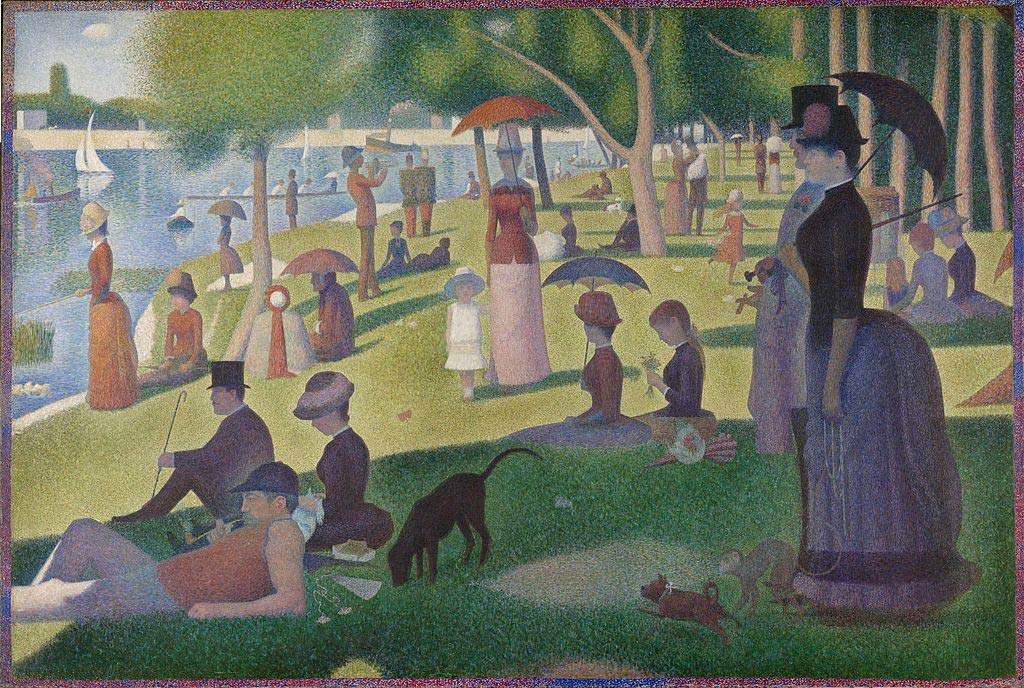

In 1884 Seurat detected a similar intention to Cézanne’s with paintings that showed concentration on composition and deepened the science of color. Taking as his starting point the Impressionist practice of using broken color and the juxtaposition of complementaries, he sought to achieve luminosity through optical formulas with tiny dots of contrasting colors chosen and placed side by side, to merge at a distance into a dominant color. This highly theoretical technique, called "pointillisme“ in Italian puntillismo or pointillism, was adopted by many contemporary painters and formed the basis of the style of painting known as ”Divisionism“ or ”Neoimpressionism."

Gauguin, too, after exhibiting with the Impressionists until 1886, renounced them in search of a more instinctive aesthetic, moving away from the sophisticated urban art world of Paris and manifesting an ever-increasing “primitivism” in his life choices and artistic vision. He found inspiration in tribal iconography, moving away from Western conventions, in medieval stained glass windows and manuscripts, and explored the expressive potential of color and contour line, from which came the technique of "Cloisonnisme." To gradually evolve toward increasingly exotic and sensual color harmonies when he went to live among the Tahitians. Gauguin sought a type of direct relationship with the natural world and treated his painting as a meditation on the meaning of human existence. Symbolic and highly personal meanings, which represented a synthesis between formal elements and the idea or emotion they conveyed to him, were particularly important in his quest between travel and exploration.

Same said for Van Gogh who, having arrived in Paris in that same 1886 in time to attend the last exhibition of the Impressionists, quickly adapted their techniques and color to express his emotional responses and his memories and ideas. In his mature works, now icons in art history of all time, the short brushstrokes of Impressionism became curved, vibrant lines of color that described his vision about the natural landscape, people, and himself. His relationship with Gauguin was important, and before Gauguin left for Tahiti, the two in 1888 lived in Arles for a few months and worked together, influencing each other.

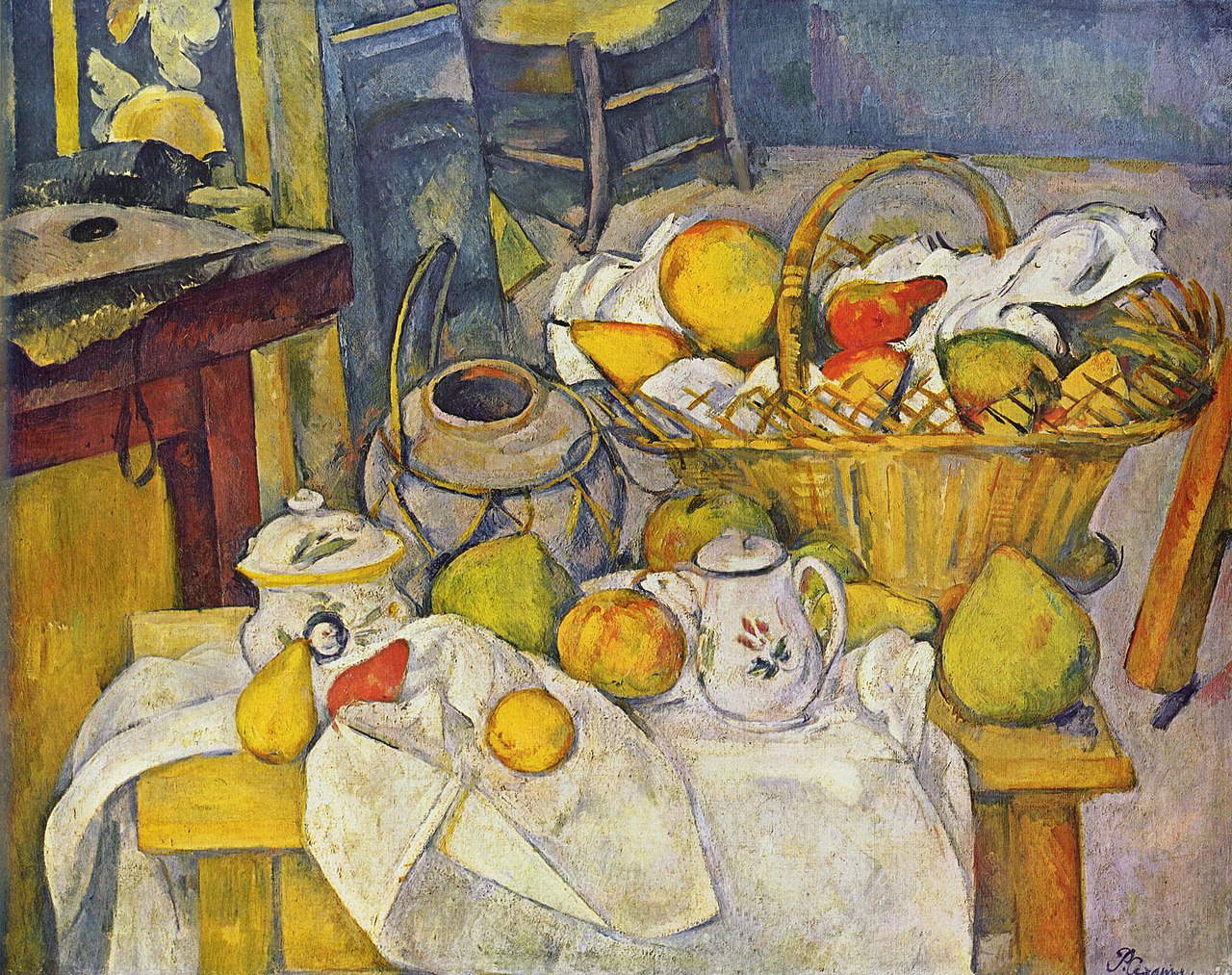

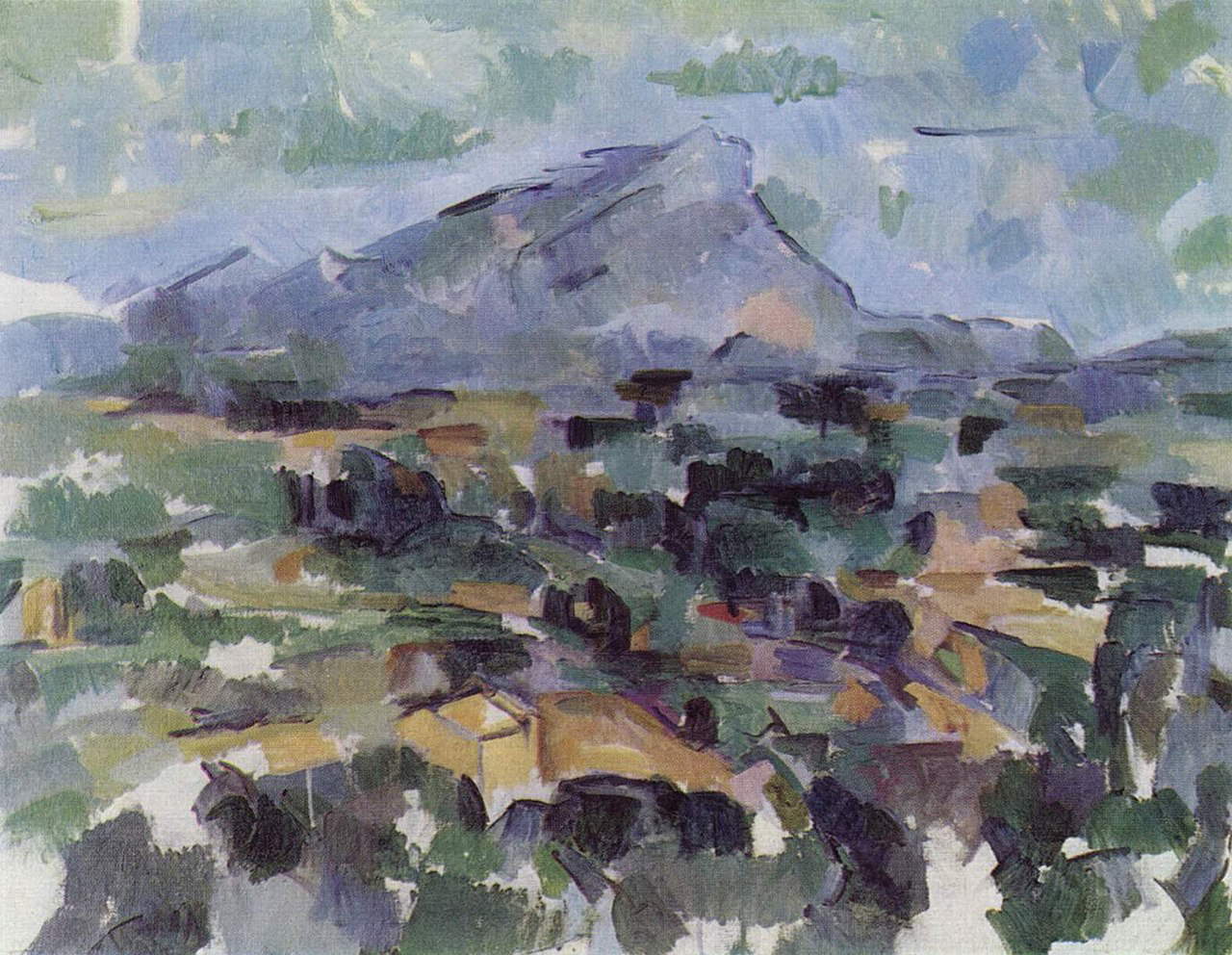

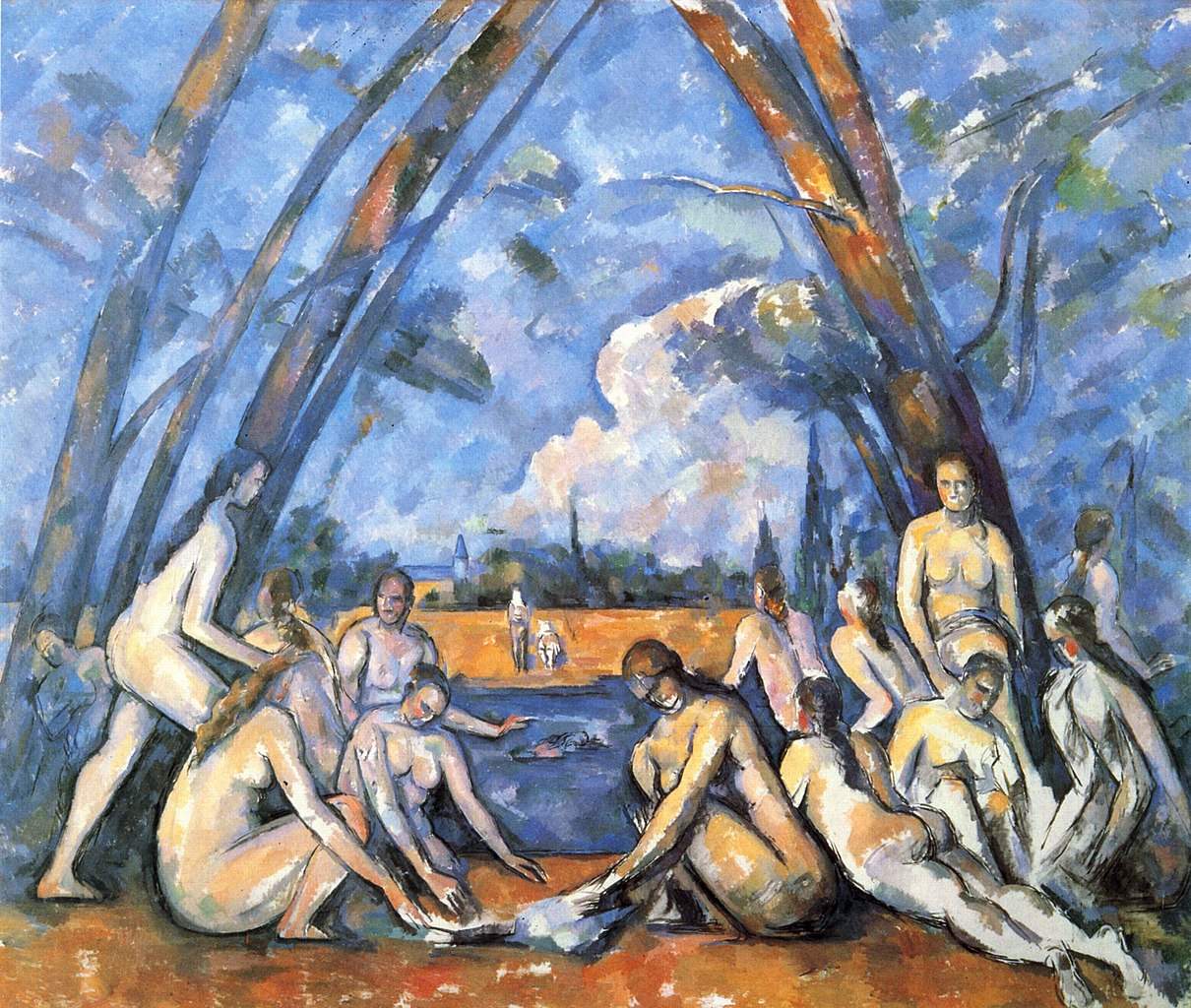

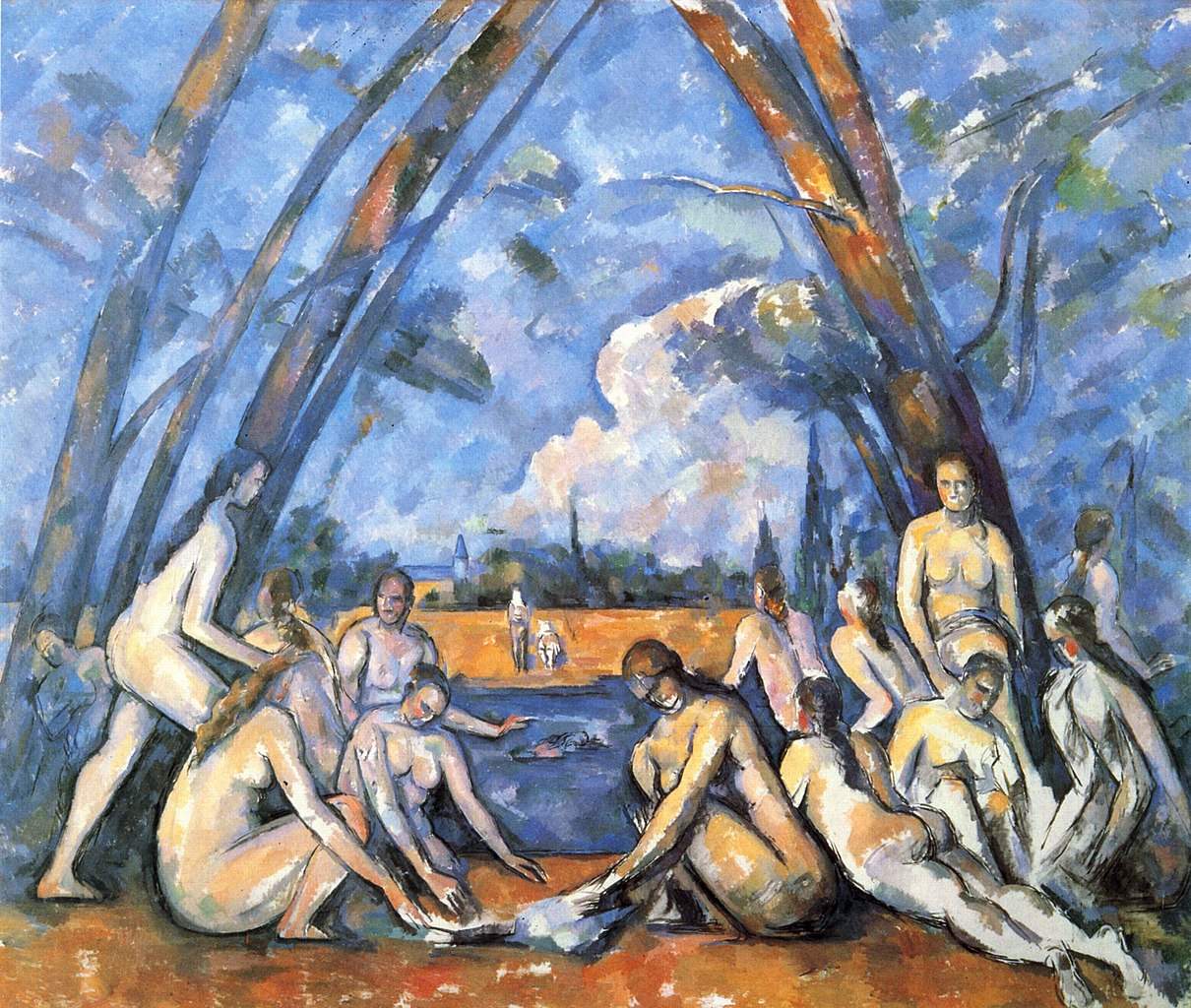

In Postimpressionism, many artists were engaged in seeking vivid styles in composition, color, and symbolic content. The emphasis on expressiveness meant that city life was no longer the dominant subject. Cézanne devoted himself mainly to still lif es(The Kitchen Table, 1889-1890), portraits(Madame Cézanne in the Yellow Armchair, 1888-1890) and landscapes (Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1905), always trying to articulate a ’compositional organization, convinced that nature could be described “in the terms of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone,” that is, the simplest geometric components. Using planes of color to create these forms, he combined parts of figures in the foreground with elements of the background, surface and depth together. Indeed, many art historians consider The Great Bathers (1900-1906) his masterpiece, in which he employed this technique of building the image with lines and geometric shapes through a dense impasto of colors, spread with a palette knife rather than a brush. The bodies, trees, and landscape are planes of color that make up a scene that reads both simultaneously and consecutively along more than 2 meters in length. The visual effect of the bathers, sharply defined in black outlines but merged with the tree branches in the landscape behind, represents a visual shift that foreshadowed the future of modernist painting.

Seurat developed a scientific painting style of dots and marks each made of a unique color, skillfully juxtaposed to compose themselves in the viewer’s eyes. Exemplary is the large canvas A Sunday Afternoon on the Isle de la Grande-Jatte (1884-1886), in which Seurat applies color in dense fields of tiny dots to mimic the vivid and vibrant appearance of natural light, which is also the result of blending various precise colors. One of the earliest examples of the artistic reaction to the Impressionist movement. When viewed closely, the painting appears as almost abstract, embroidery-like. When viewed from a proper distance it comes into focus. Seurat carefully placed each stitch in relation to the surrounding ones to create the desired optical effect. He did this to give structure and rationality to what he perceived to be disorganized in the Impressionists’ vision, although he drew on elements typical of them, such as the rendering of light and shadow and subjects such as the recreational activities of the Parisian bourgeoisie(Circus Show, 1887-1888).

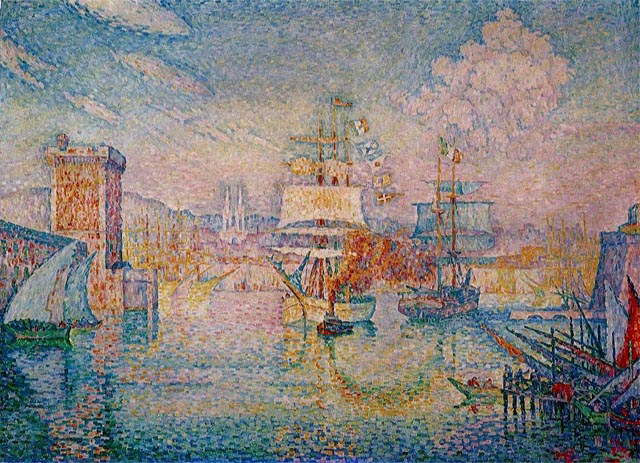

Paul Signac followed closely in Seurat’s footsteps in these explorations(Entrance to the Port of Marseille, 1911) by going on to enlarge small dots into squares or rectangles of color.

Gauguin developed further ideas of overcoming earlier painting with the theory ofsynthetism.�? According to his principles, the final visual form was determined by a synthesis between the outward appearance of natural features and the aesthetic considerations that bodies and nature aroused in him.Gauguin discarded shading, modeling and perspective from a single point of view, using pure color, strong lines and flat two-dimensionality to elicit visceral emotional impact. Seeking, as mentioned above, a degree of spiritual freedom and primitive whiteness, he gained experience in Brittany, northern France, with rural religious communities and immersed himself in various Caribbean landscapes, while also educating himself in the latest French ideas in painting and color theory, which inspired works such as The Vision After the Sermon (Jacob’s Struggle with the Angel) of 1888. The painting depicts a revelatory vision of Jacob grappling with an angel, in which the crowd of worshippers experiencing the vision is in the foreground, and the biblical struggle appears against a red background, representing religious emotion. As this work and others such as The Yellow Christ of 1889 show, the painter gradually experimented with new approaches to color, paving the way for a new style of painting called "symbolism." It was a new way of understanding painting that married the observation of the everyday with mystical symbolism, strongly influenced by the popular aspects of the arts primitive of Africa, Asia as well as French Polynesia. When in his last period he took to painting portraits of Tahitian women(Manao Tupapau. The Spirit of the Dead Watches Over, 1892) he revealed his ability to suggest deeper meanings behind the superficial appearances of reality. A precisely synthetic painting that functioned as a symbolic, rather than merely documentary, reflection. Gauguin’s rejection of his European family, society and the Parisian art and urban world for a life elsewhere became a model for the role of the mystic-errant artist(Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?, 1897).

Van Gogh also embodied the rejection of Impressionist optical observation in favor of emotionally charged representation, which appealed to the viewer³’s heart by using an impulsive, gestural application of paint and symbolic colors to express subjective emotions. He is certainly considered one of the most gifted and emotionally troubled artists of the modern era, although severely underrated during his lifetime.

The first reevaluated masterpiece The Potato Eaters of 1885 already represented an outlier at the time it was painted, given the dull color palette and the choice to depict the squalid living conditions of peasants, when the Impressionists had dominated the Parisian avant-garde for more than a decade with their light palettes and scenes of bourgeois affluence. Van Gogh moved toward saturated colors and broad brushstrokes evocative of inner turmoil, however, influenced by a variety of sources, not the least of which was his fondness for stylized representations of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints.

Combining influences as diverse as the loose brushwork of the Impressionists and the strong outlines of Japanese woodcut, Van Gogh arrived at a truly unique mode of expression in his paintings. Using the impasto technique, or the layering of wet paint, he structured a surface in the sense of depth and emotional force. In his work, too, dark, thick outlines and flat stripes of color stand out. He remained faithful to dark tonal painting until he met Seurat and Signac in Paris, who introduced him to the doctrine of complementary contrasts.

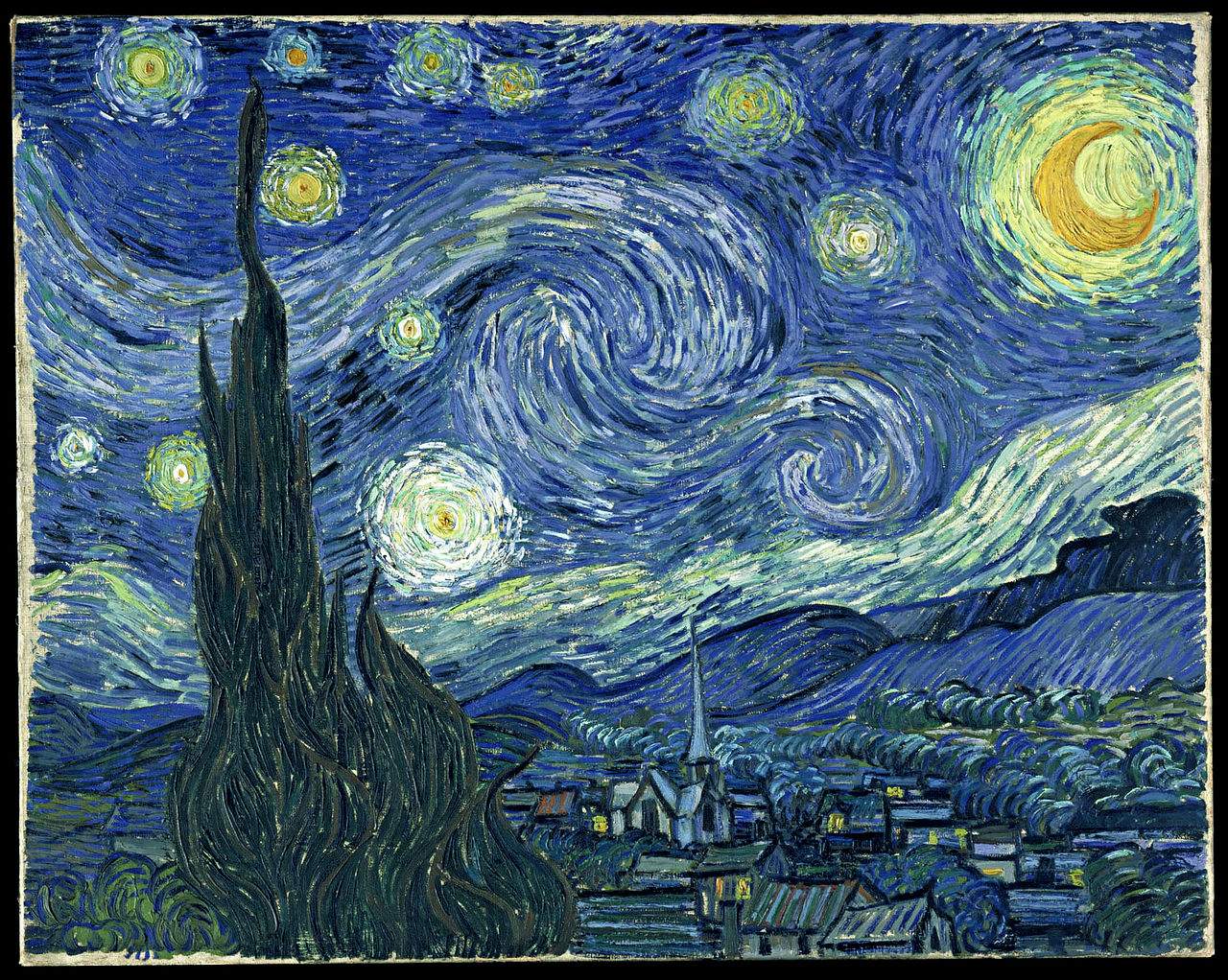

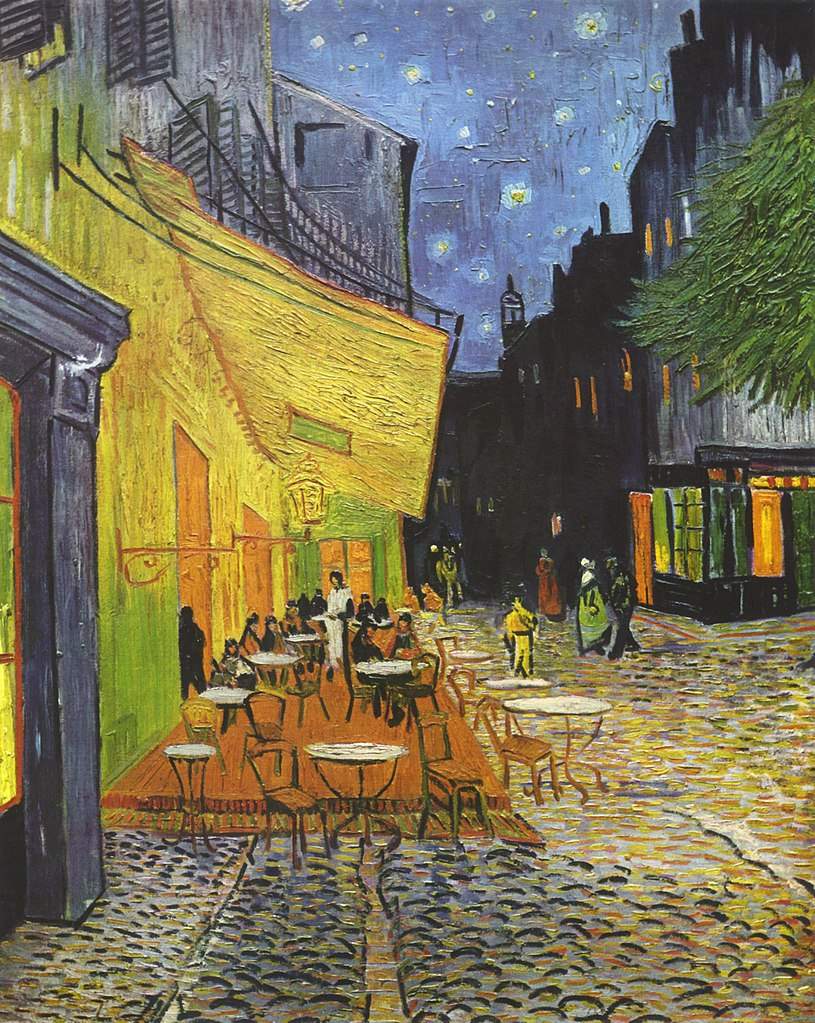

He rewrote by interpreting them, with a recognizable personal trait, some traditional genres such as flower painting, of which the Sunflower series is famous; self-portraiture, of which he produced many, and portraiture(Portrait of Joseph Roulin, 1888); and last but not least landscape(Wheatfield with Flight of Crows, 1890), in which lines and relief textures played a key role(Starry Night, 1889). He expressed in his more than two thousand works a personal vision of nature, which almost always implied human intervention and presence. Houses, villages and fields in which man’s labor was evident, whose dignity as a worker at all levels he managed in figurative terms to render. From peasants(Sower at sunset, 1888) to prostitutes, self-representing and portraying figures in their actions and roles in society, even when mere frequenters of night cafes(Café terrace in the evening, Place du Forum in Arles, 1888). Van Gogh’s unstable and moody temperament, which led him to bind art and life inextricably to extremes(Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889), became symbolic of the image of the tortured artist. His story of misunderstood talent set an example for many artists in the 20th century.

|

| Postimpressionism: the baptism of contemporary art. Developments, themes and styles |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.