Pop Art: the history, styles, artists

The term Pop Art comes from the contraction of the word popular and refers to a visual language that European and American artists pursued in the 1960s. Like the phenomenon of pop music, Pop Art addressed the new consumer society, spreading at a moment in history following the World Wars, when Western countries found themselves gravitating to the orbit of the United States, swept up in the thrusts of economic recovery, all aimed at the abandonment of protectionism, and directed toward the construction of a system based on free trade. It was the era of the development of transportation, the time of the cinematograph, TV and comic books, and photostories.

The world of communication saw exponential growth, and that very one created the preconditions for the birth of Pop Art: the patterns and registers used for rapid, commercial broadcasting were revisited in an aesthetic key by artists, who proposed them to a new, ever-expanding audience. In response to an ever-expanding demand, the language of the media and also the language of art were expressed with new tools, including repetition and seriality. Hence came the serialisation of the icon, from Kellogg’s Cornflakes to Marilyn Monroe. In general, Pop Art resumed the operation of linguistic and mental mediation that was already characteristic of New Dada, but it was not born with the typical connotations of the avant-garde, with a manifesto and an aggregation of artists. It was rather an environment, a climate in which different research paths met: the British Eduardo Paolozzi (Leith, 1924 - London, 2005) and Richard Hamilton (London, 1924 -2011); in America Roy Lichtenstein (New York, 1923 - 1997), Andy Warhol (Andrew Warhola Jr.; Pittsburgh, 1928 - New York, 1987), Claes Oldenburg (Stockholm, 1929 - New York, 2022), Robert Rauschenberg (Port Arthur, 1925 - Captiva, 2008), partly Jasper Johns (Augsburg, 1930), who was among the founders of New Dada. The Italian scene was not to be outdone: from Michelangelo Pistoletto (Biella, 1933) to Mario Schifano (Homs, 1934 - Rome, 1998), Franco Angeli (Rome, 1935 - 1988) and Tano Festa (Rome, 1938 - 1988), Roman artists revisited their own artistic tradition by filtering it through the lens of popular imagination.

Origins and developments of Pop Art

The 1950s were marked by general prosperity, a lightness that spread after the tragedies of the war events. The birth rate rose, the population increased; the new availability of labor-power allowed industries to experience a surge, finding themselves having to respond to a demand having more and more of a mass character. To do so, they resorted to serial production and the study of advertising, with a view to facilitating a commercial sale: a product was being sold, but first and foremost its image.

For this it had great relevance to mass communication, instantaneous and rapid, able to keep up with the pace of that new, fast-rising world. Availability, immediacy and speed were the conditions that imposed themselves in so many fields, from commerce to transportation. This adrenaline-fueled world was a response to the more tragic events experienced in the first half of the century: the constant glance toward progress and the future was a way to banish the memory of the obscenities of the wars that had just passed.

Against this postwar backdrop, although the “dream” of America appeared more and more within reach, it was in Great Britain that the first pop experiences manifested themselves. The wartime arrival of new U.S. products had stimulated great curiosity. The image of new offerings and serial products was revived in an aesthetic key in the mid-1950s by British artists such as Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Peter Blake (Dartford, 1932). There were a number of exhibitions: in 1955, Man, Machine & Motion was opened at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, where photographs, montages, and installations looking at the latest technological developments were displayed. The following year, in August 1956, This is Tomorrow opened at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. Twelve environments created with the collaboration of artists and architects were presented here. The exhibition marked the consecration of British Pop art and fixed a point on the situation of contemporary man in mass-media society.

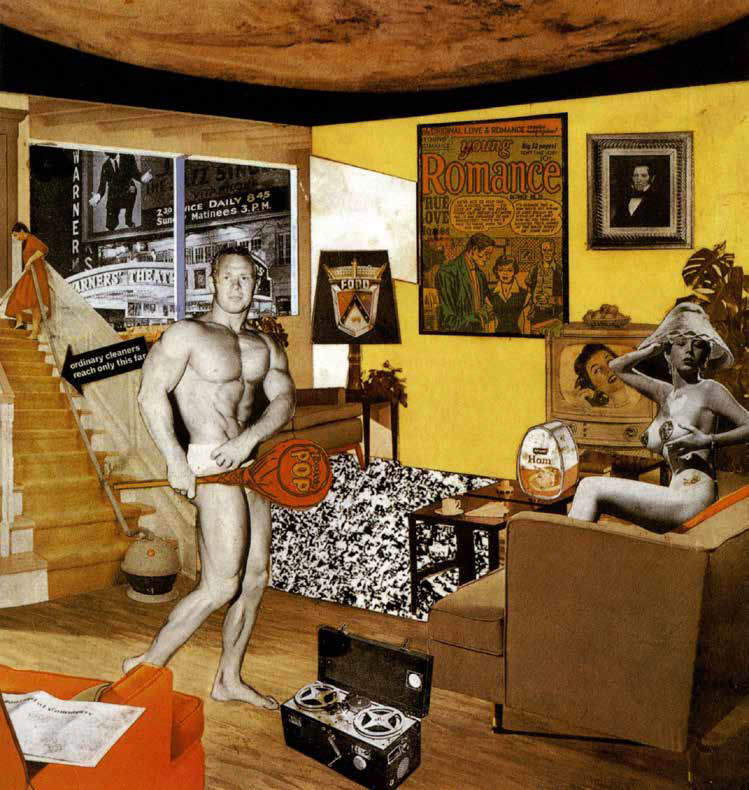

On this occasion, a photo collage by Richard Hamilton that contained all the useful elements to define the Pop language was exhibited with great success. A room full of household appliances, a comic book poster. From the window in the background is a reference to the cinematograph and winking illuminated billboards. One can even read the word pop. The name of the collage is Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? Still in the English sphere, this artistic trend was later nurtured by the imagery of Peter Blake, who curated the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album; but also by sculptor Allen Jones (Southampton, 1937) and Eduardo Paolozzi with his industrial materials.

However, British Pop art always remained somewhat nostalgic, anchored in the historical tradition of good European painting, with a restrained, sophisticated, formal result: just think of painter and set designer David Hockney (Bradford, 1937), his landscapes, where painting is restrained compared to the frenzy pertinent to Pop art. British Pop Art lacked the scandalous effect that would definitively make it suitable for mass reception, that same communicative intentionality found in the magazines.

That artistic will, which would later enshrine its artists as quasi-Hollywood characters, exploded with American Pop Art: popular art found fertile ground in the United States, where products ready for large-scale consumption were already circulating. Mass media, advertising had accustomed the public to an idea of readiness, of immediate availability. The idea was seductive and, meanwhile, a persuasive operation for a growing middle class. This created and prepared dimension attracted large segments of the population, fostering, after years of abstract and informal, avant-garde art, a return to the practical, functional, concrete object to be owned, selling not only the object but the idea of material stability and security.

In the 1960s, American art responded to the new mass culture by creating reassuring goods, images, and signs that could fulfill the demands of large numbers of viewers and consumers. There was a desire to satisfy anyone who was part of the general public, promising an idea of personal enrichment and success: think of the artist Andy Warhol, of the famous phrase attributed to him, “In the future everyone will be famous in the world for fifteen minutes” (1968). The year 1962 was a pivotal year for U.S. Pop Art: several solo exhibitions of what would later become the great artists representing Pop Art took place. The New Realists exhibition mounted by Sidney Janis and the Pop Art Symposium, organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, were held. These events indicated a shift in American artistic attitudes away from the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock and now turned to the mass and monumentalization of advertising iconography. Hence Tom Wesselmann ’s (Cincinnati, 1931 - New York, 2004) slices of domestic life and Roy Lichtenstein’s comic universe, which aroused great interest in the Italian-American gallerist Leo Castelli.

Italy also had its part in the establishment of this artistic movement, representing a specific case for several reasons. At the time of the spread of Pop Art, the Peninsula was experiencing a full economic boom, witnessing a vertiginous growth in demand and consumption, between the birth of household appliances or the construction of highways. The Italian art scene opened up to welcome the main protagonists of Pop and New Dada art at the 1964 Venice Biennale: that year Robert Rauschenberg won the International Grand Prize for Painting, confirming the role of U.S. Pop Art in Europe and bringing that kind of artistic research to Italy as well, since other Italian artists such as Mario Schifano, Franco Angeli and Tano Festa were on display.

The aesthetics of these artists are perfectly traceable to the Pop register: at the same time, that register was connoted with a local taste, which never abandons the Italian artistic tradition. References to Futurism, Metaphysics and the reflection of past works are always present Franco Angeli’s La lupa di Roma (1961), or in Mario Schifano’s Futurismo rivisitato (1965) or Michelangelo secondo Tano Festa (1966). A look at Italian masterpieces was inevitable, as Tano Festa himself pointed out, "I feel sorry for the Americans who have so little history behind them, but for a Roman artist and what’s more, one who lived within a stone’s throw of the Vatican walls, popular is the Sistine Chapel, the true mark of Made in Italy." In general, pop artists worked to construct a system of images and signs that became codified within a popular imaginary. In their works, they did not adopt a polemical sense with respect to consumer society: rather, Pop Art was grounded in that society, so it rather invited an awareness of the radical changes taking place in culture and comnunication, inviting reflection on how these developments affected the life of contemporary man.

![Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (1964 [1969]; acrylic print on board, 50.8 x 50.8 x 43.2 cm each box; Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum) Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (1964 [1969]; acrylic print on board, 50.8 x 50.8 x 43.2 cm each box; Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/fn/andy-warhol-brillo-boxes.jpg)

The major exponents of Pop Art

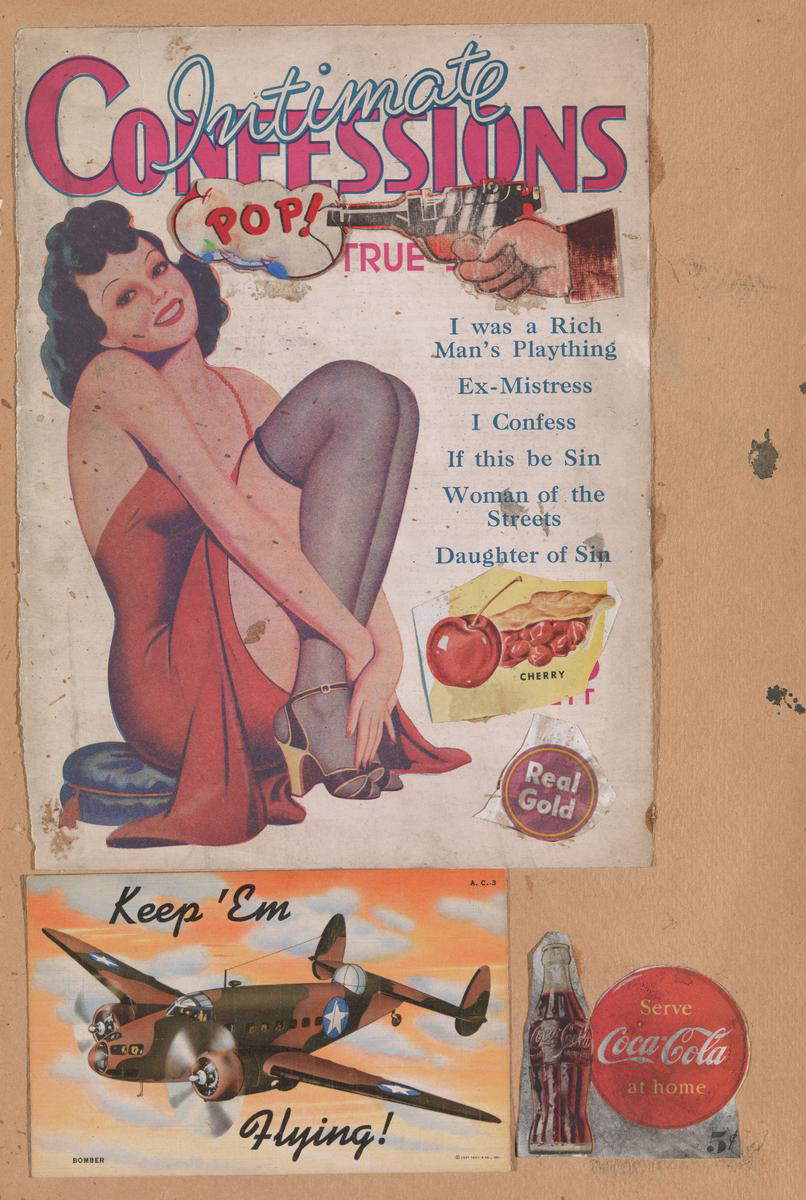

As anticipated, Pop Art was not an organized movement so much as an artistic climate where even different artists found themselves working. In the spring of 1952, in Great Britain, Eduardo Paolozzi projected his collages at a conference of the Institute of Contemporary Art. Made beginning in 1947, Paolozzi put together clippings from advertising newspapers, magazines and comic strips, setting them up as a repertoire of messages to be analyzed, mostly material from the United States. For example, in I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything (“I Was a Rich Man’s Toy”) appear words, famous logos and images of transportation, icons that composed the imagery of those years of evolution. In these works the advertising seduction of the new iconic images coexist along with the influence of the Avant-gardes: the collage is Dada-surrealist, as is also Dada the inclusion of words.

Despite its success, the first pop work recognized as such was by British artist Richard Hamilton (1922-2011): Just what’s it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (“What is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?”) from 1956, was exhibited at the This is Tomorrow exhibition. In this paper collage, pop culture quotes range from Marilyn Monroe to the jukebox. A huge lollipop with the word pop prominently appears as well. With this work, destined to define British pop, Hamilton produced an inventory of British popular culture, an invitation to reflect on how it had departed from the streets and become part of the most ordinary homes, influencing the lifestyle of contemporary man.

In a pictorial realm, David Hockney (1937) demonstrates a resistance on the part of British art to the explosiveness that would later connote American pop art. British painting contains itself in the expression of an attachment to the pictorial tradition of the past. With A bigger splash, 1967, David Hockney recounts the rich, carefree life he lived with his move to California with the use of acrylic paints in flat, precise backgrounds, containing the atmospheres in a geometric, aseptic environment. Among others, Peter Blake (Dartford, 1932) helped shape British pop imagery, remembered author of the cover of The Beatles’ Sergent Pepper, which became an icon of pop London in 1967. British pop art also registered the new desires expressed by mass culture: Allen Jones explored the theme of eroticism with a series of sculptures featuring the woman-object theme, such as Chair, from 1969, now in Aachen.

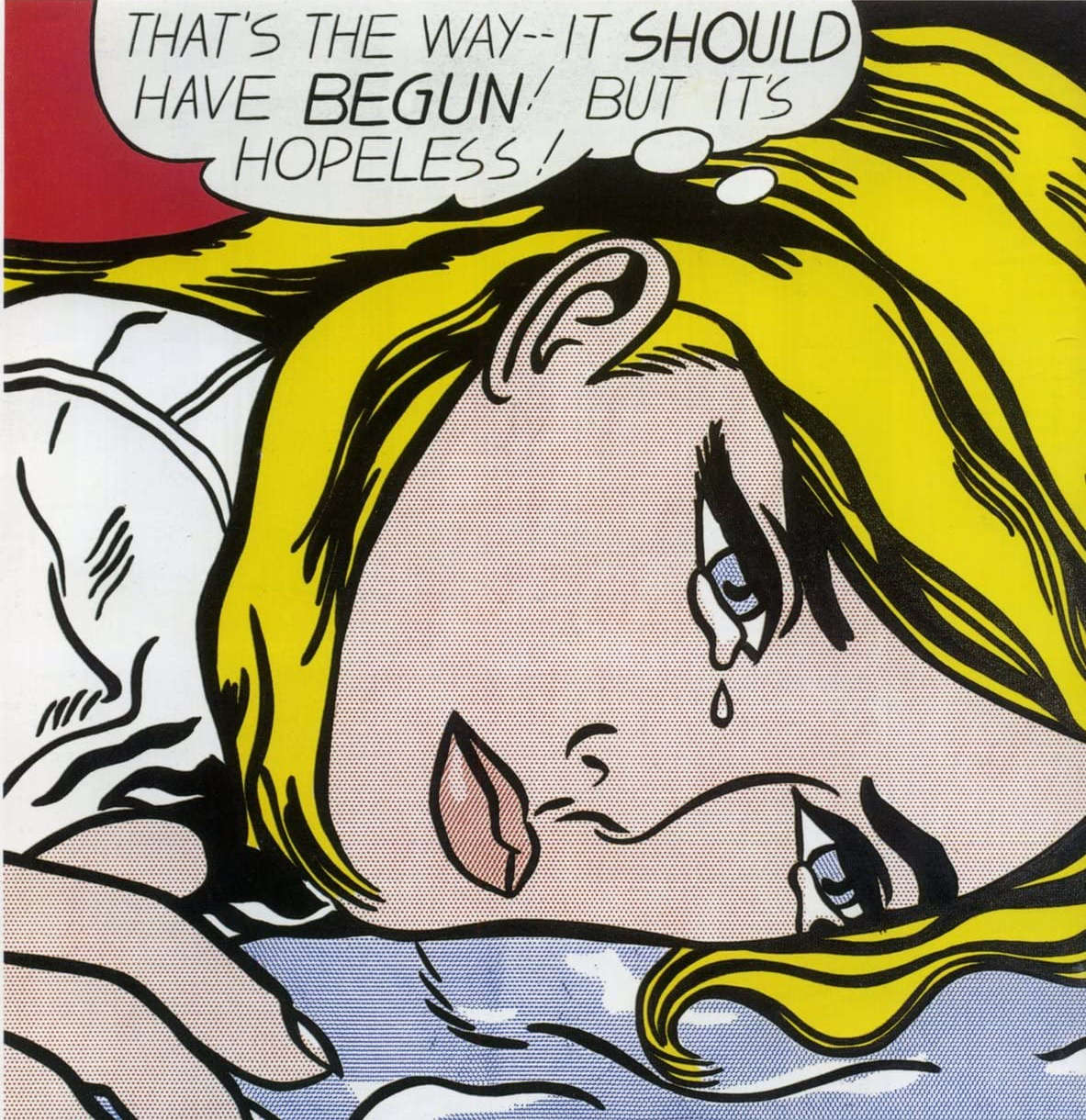

In the United States, Roy Lichtenstein drew on the world of comic books, taking a cold light from them and the filter of the typographic screen. In Hopeless (1963), Lichtenstein reproduces a cartoon by isolating it from its narrative context. The lettering that accompanies the protagonist loses a meaning and at the same time acquires a universal one, within the reach of everyone’s interpretation. Lichtenstein works with the filter of the typical comic book form, particularly the “graining” effect, even to repurpose masterpieces by the great masters of the past, as he did in 1969 with Rouen Cathedral (Seen at three Different Times of Day).

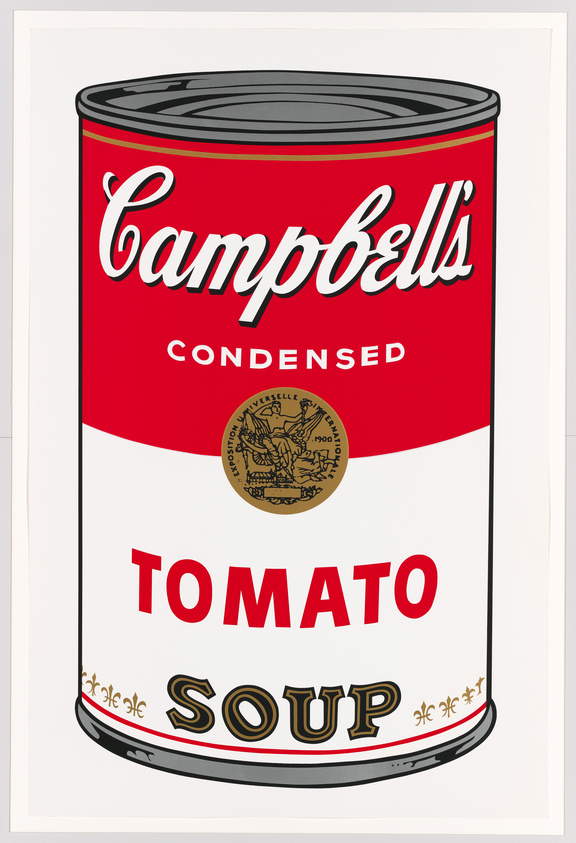

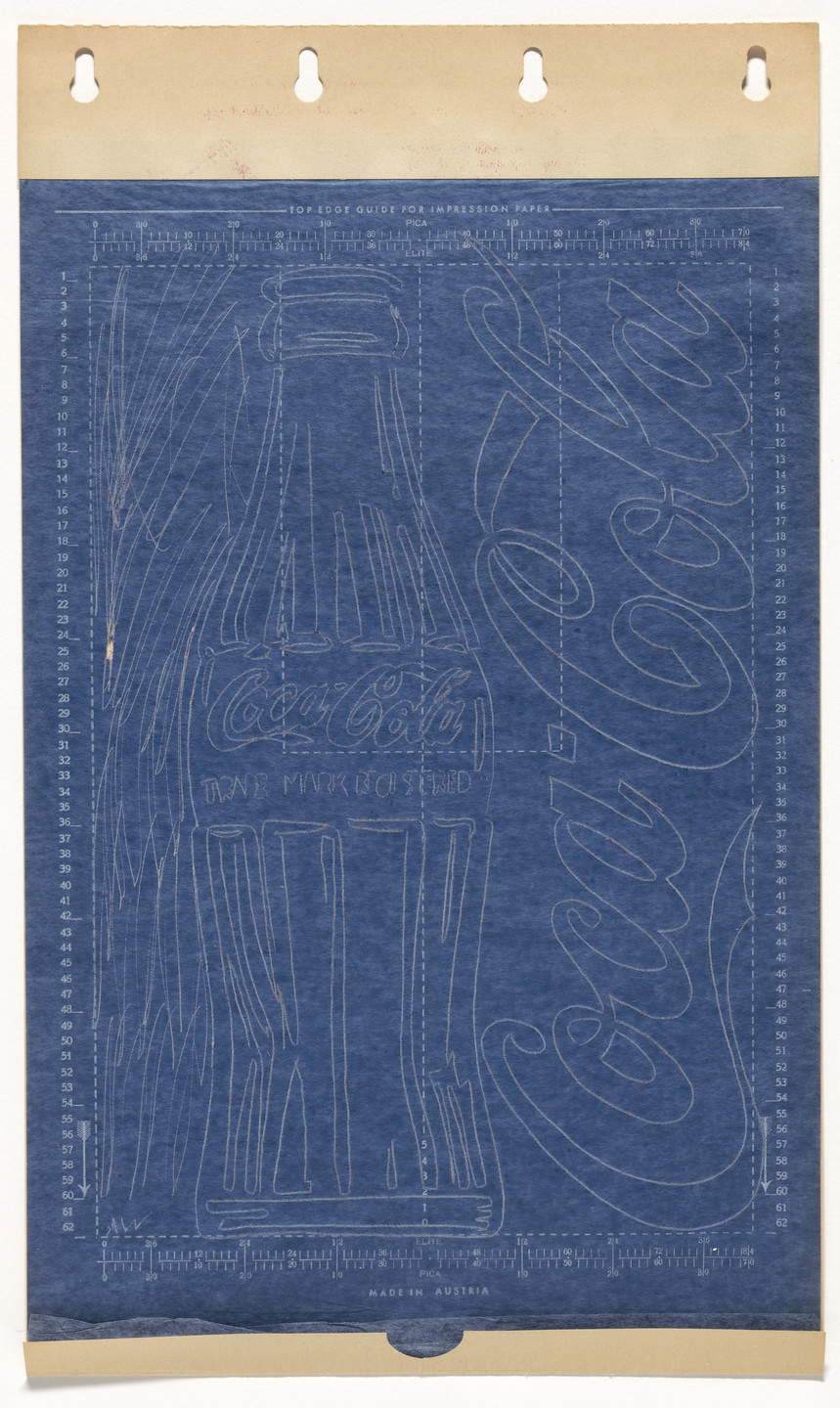

Acclaimed artist and figure of American Pop art itself is Andy Warhol. An emblematic figure in the American context of the 1960s, he changed the very idea of the artist by introducing the possibility of theartist who was his own entrepreneur, communicator, and part of the commercial and artistic system. Warhol elaborated a detached language, impassive in its recording of reality: for this he founded the Factory, that is, a company for the production of works, employing silkscreen printing for an industrial realization on canvas, with a team of artists working under the supervision of Warhol himself. It is from here that the reiteration of icons such as the Campbell soup can, the Coca-Cola bottle and the Brillo detergent box, or even Kellog’s Cornflakes comes out. Warhol illustrates the seriality of these objects as well as famous people.

Drawing on a famous photograph circulated after the film Niagara (1953), Warhol serially reproduced Marilyn Monroe: Shot Orange Marilyn, from 1964, is a silkscreen print on canvas, now at the Andy Warhol Foundation in New York. The object (or even the celebrity, the news fact) is lifted from the narrative by means of reiteration. Pop Art expands its communicative possibilities and eventually sells it to the mechanisms of consumption.

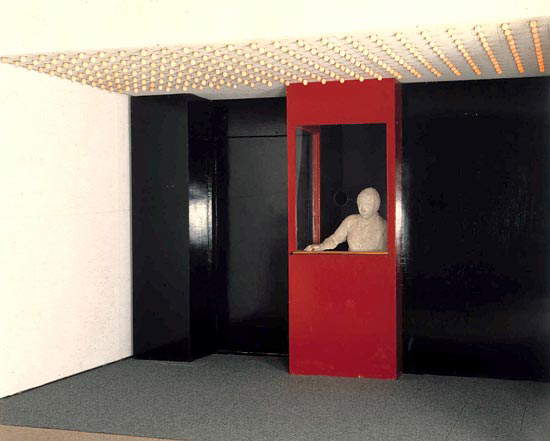

Claes Oldenburg made works that replicated everyday, commonplace objects with the use of materials reproduced on a large scale with new, synthetic, and colorful materials, such as Giant Fagends (“Giant butts”) is from 1967. Also American is artist George Segal (Great Neck, 1924 - Santa Rosa, 2000): he differs from previous artists in a different way of revisiting contemporary society. The artist recreates environments in a three-dimensional sense. Within these he places plaster casts that reproduce people caught in the simplicity of an everyday gesture. Some at work, some resting, some at the bar. In The Moviehouse, made in 1966-67, a woman plies her trade as a ticket taker behind the movie theater booth. What Segal did was to talk about anonymous figures that bring the mind back to the existential poetics typical of the American artist Edward Hopper, thus tracing the art of the past, a dip into American realism.

Thinking about the art of one’s own tradition was something that the Italian Pop artists of the 1960s did: Mario Schifano was initially inspired by the American artists Johns and Warhol, with whom, moreover, he exhibited in the group show The New Realists. Schifano used elements of urbanism a lot: advertising signs, images taken from the media. With Futurism Revisited, made between 1965 and 1967, the artist recovered a historical photograph of Futurist artists taken in Paris in 1912, depicting Luigi Russolo, Carlo Carrà, Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini. The photograph was repurposed by the artist with colored silhouettes set in a checkerboard.

Franco Angeli, like Schifano did, also looked to mass imagery, but turning to the serial repetition of icons. This time they are not commercial products; he preferred to look to an imagery that is yes popular, but more historicized. His subjects are the Capitoline she-wolf and the hammer and sickle. Angeli vigorously repurposed them, “because by dint of seeing them, no one paid attention to them anymore.” From the early 1960s also came the experience of Tano Festa, who retrieved fragments of famous works by masters such as Michelangelo, from whom he made a cycle, Michelangelo according to Tano Festa (1966), made with the tracing technique from a projected image. The resulting two-dimensionality functioned as the basis for a compact drafting of bright, strong colors reminiscent of the language of mass communication, with a slight suspension of metaphysical flavor.

|

| Pop Art: the history, styles, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.