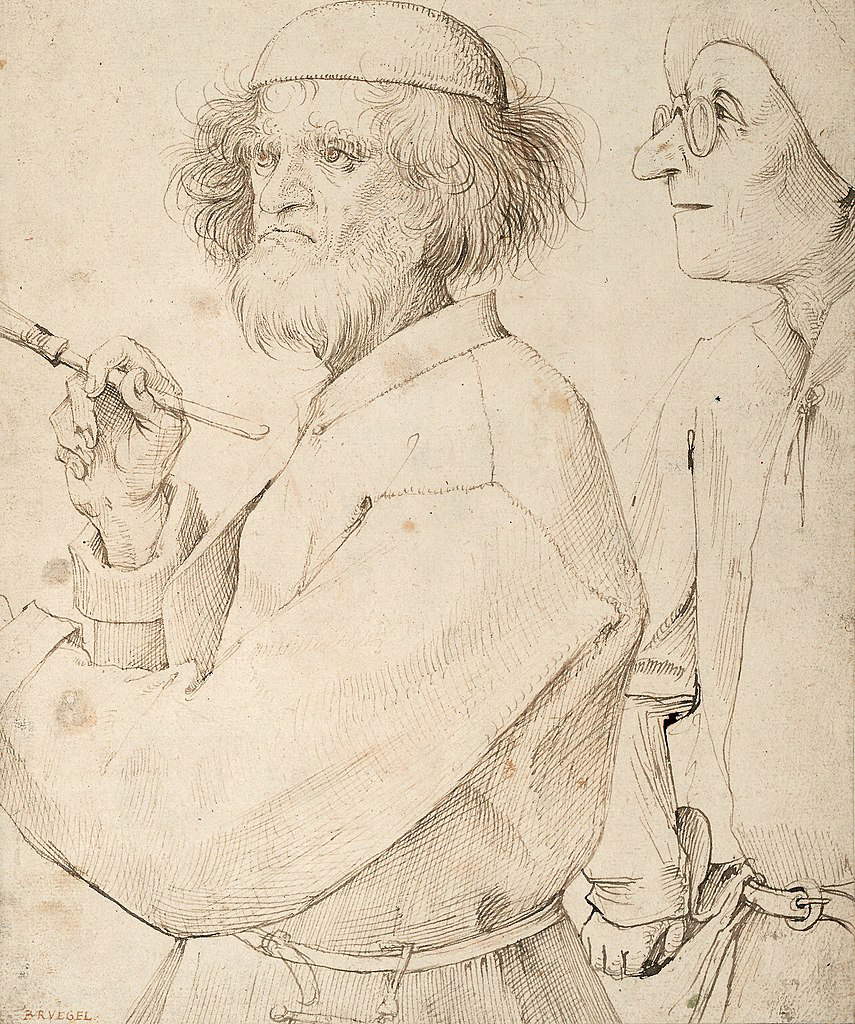

Pieter Bruegel, called the Elder (Breda, c. 1525-Brussels, 1569), was the greatest artist in the Netherlands in the 16th century, exerting a strong influence on the painting of the time and later, and through his sons, Pieter and Jan, became the ancestor of a dynasty of painters that survived into the 18th century. Of his output that has come down to us, many drawings, engravings, and just over forty authenticated paintings, the landscapes and scenes of peasant life, often rendered in a humorous, caricatured, and grotesque sense, through a minuteness of detail typical of earlier Flemish painting, are particularly well known. With Bruegel, the life of the people gained importance; nature and humanity were an inexhaustible source of his representations.

Bruegel the Elder’s artistic development is traced through the signed and dated works, otherwise, from the uncertain year of his birth, the details of his life are not known precisely. Biographical information is mainly derived from the 1604 "Schilderboek " or “Book of Painting” by the Flemish Karel van Mander, a biographer of artists as the Italian Giorgio Vasari had been. What is known is that around 1551 Bruegel set out on a trip to Italy, where in addition to a series of drawings of the places he visited, he also produced his first signed painting in 1553.

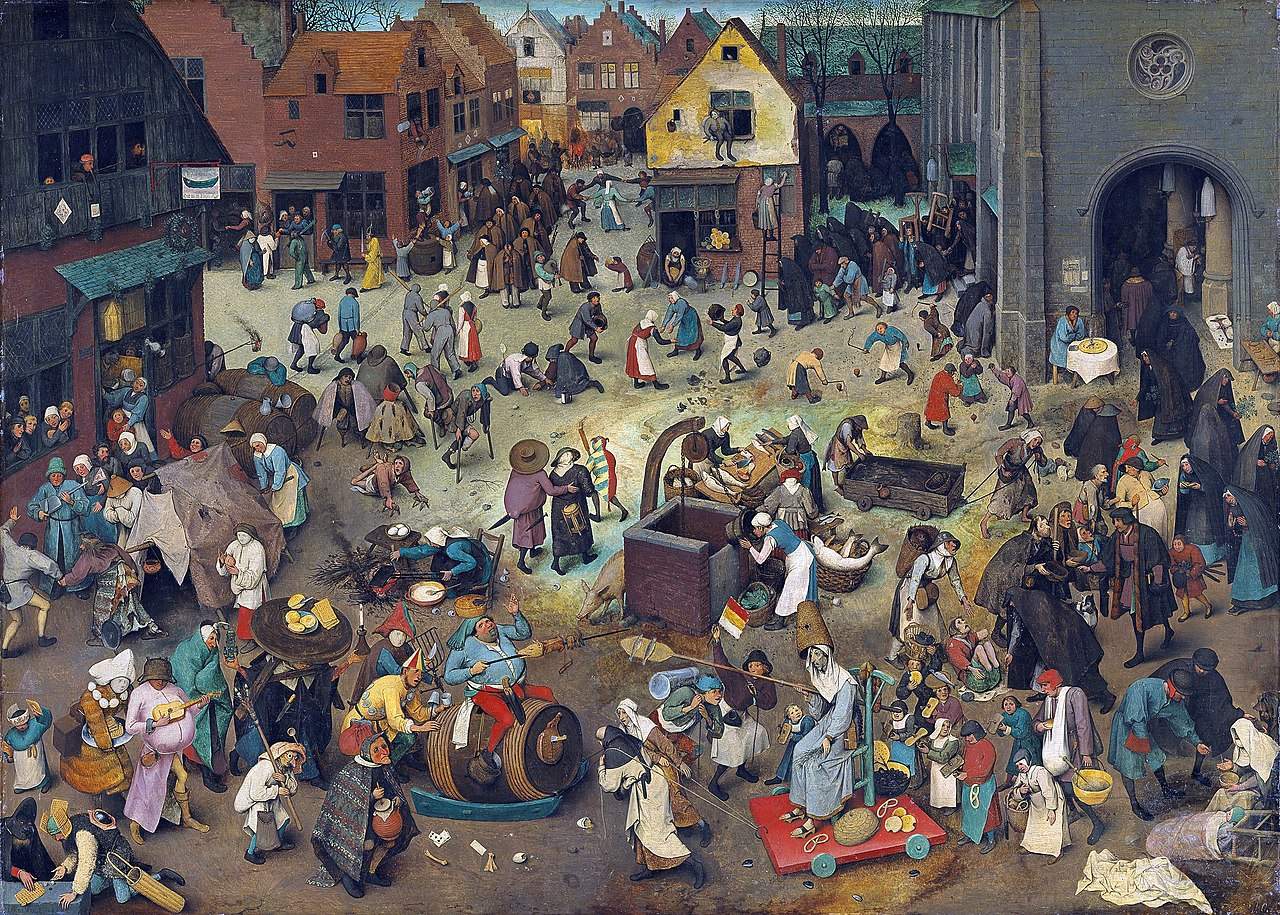

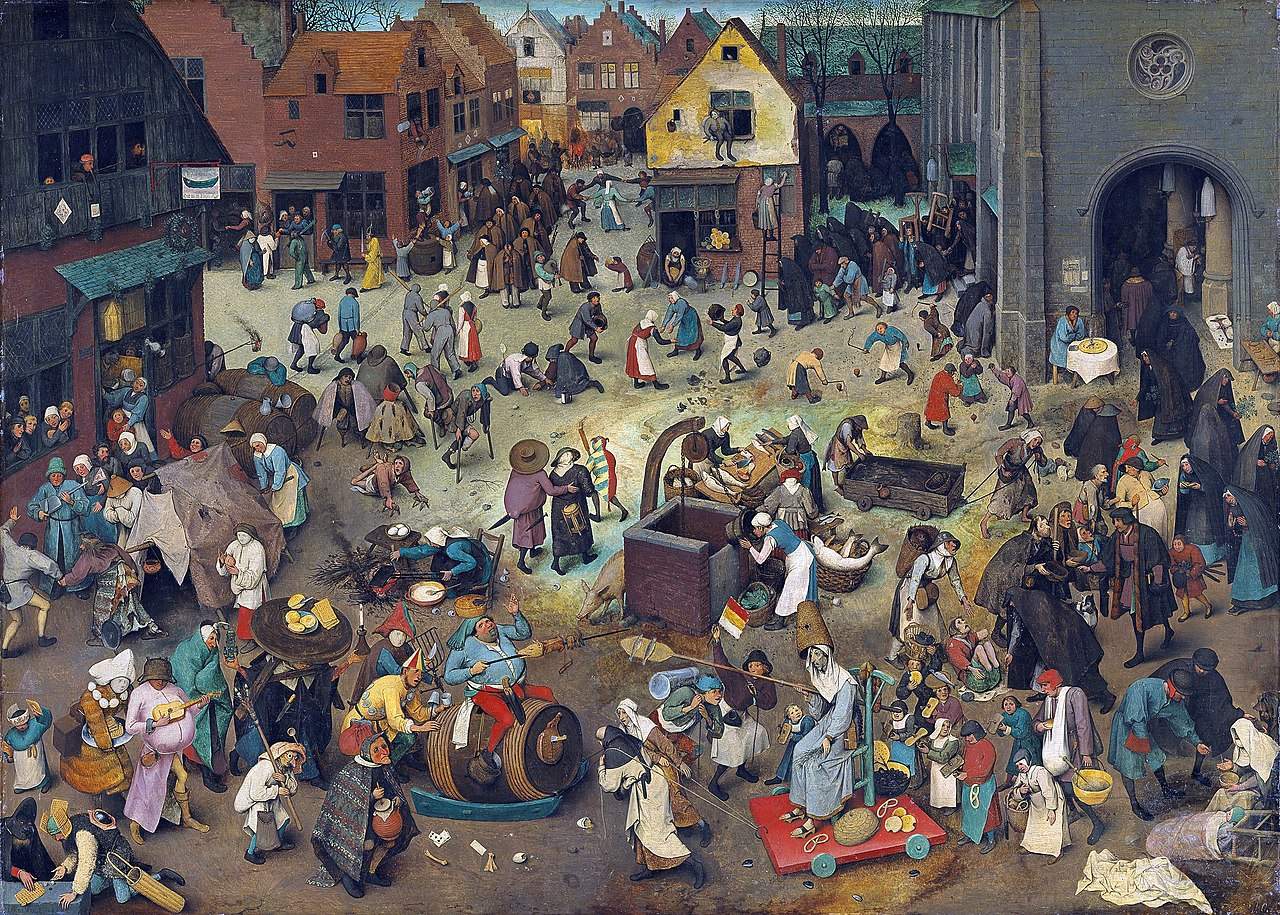

On his return to the Netherlands, he achieved some fame through satirical and moralizing images. A distinguishing feature of the painter’s work is hisdeparture from the models of European Renaissance art to reserve the scene for ordinary individuals and no longer just heroic personalities or glorious events. His work focused on themes such as rural working life, religion and superstition, and political and social intrigue. Many masterpieces portray Dutch customs and habits, translating colorful idioms or popular verbal expressions into pictorial images, seasonal landscapes and realistic views of peasant life and folklore, or biblical and mythological events in scenic settings, often seen from above. He set the school for his new Protestant approach to religious subject matter. He had success in his lifetime, important patrons and commissions from collectors. The geographer Abraham Ortelius, Bruegel’s friend and collector, wrote of him, “He knew how to paint the things that cannot be painted [...] in all his works one must always be able to understand more than what has been painted,” thus indicating further meaning to look for in the paintings.

According to his first biographer van Mander, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, born Peeter Brueghel in Breda in the Netherlands around 1525, was apprenticed in Brussels to Pieter Coecke van Aelst, a sculptor, architect, and designer of tapestries and stained glass who had traveled and knew Italy.After Van Aelst’s death in 1550, Bruegel moved to Antwerp, where he received his first assignment to work on an altarpiece commissioned by a guild. The guild system was important in promoting artistic careers, and Bruegel’s professional life actually began in 1551 when he was elected to the Guild of St. Luke, an association of Antwerp painters. That year he set out on a long journey of painting and research through Italy, evidenced by drawings in loose compositions and sketches, later to become completed works for the most part after his return to Antwerp.

From several surviving drawings, paintings and engravings, it can be inferred that he traveled beyond Naples to Sicily. The earliest works from 1552 are Italian landscapes. Numerous drawings of alpine regions, made between 1553 and 1556, indicate the great visual and emotional impact the mountain experience had on him. Van Mander observed that the artist “had swallowed all the mountains and rocks to spit them back out on his return on canvas and brushes.” The mountain landscapes resulting from the tour of Italy set the standard for European art. In 1553 he certainly lived for some time in Rome, where he produced his first signed and dated painting, Landscape with Christ and the Apostles at the Sea of Tiberias. Upon returning to Antwerp around 1555, Bruegel began working for the city’s artist-engraver and principal print publisher, Hiëronymus Cock. From 1556 onward he focused on satirical and moralizing subjects, often in the fantastical or grotesque manner of Hiëronymus Bosch (’s-Hertogenbosch, 1453 -1516), whose imitations were very popular at the time.Cock exploited the opportunity by selling a relatively unknown Bruegel engraving, The Big Fish Eats the Little Fish (1556), passing it off as an original by Bosch who had died forty years earlier. Some artists were content to work as imitators, but Bruegel’s inventiveness soared and he soon found ways to express his ideas with personal expression. Bruegel took to producing pictorial works especially from about 1557 onward, developing an unmistakable compositional style and achieving the status of a significant and in-demand artist.He became interested in the human figure without abandoning the landscape and extended his experiments in this field. Alongside mountain compositions, he began drawing the woods of the countryside, then turned to Flemish villages and around 1562 to cityscapes with the towers and gates of Amsterdam.

Most of his paintings were made for collectors, wealthy merchants and church members. Among his patrons were from Antione Perrenot cardinal de Granvelle, president of the state council of the Netherlands, to Niclaes Jonghelinck, who bought his 16 paintings in 1566. By 1559 the artist had changed the spelling of his name from “Peeter Brueghel” to “Pieter Bruegel.” In 1563 he married Mayken Coecke, the daughter of his first master Pieter Coecke van Aelst, and they moved to Brussels. The marriage spawned what was later a dynasty of artists: his two sons, Pieter later known as Pieter Brueghel the Younger born in 1564, and Jan Brueghel the Elder born in 1568, as well as his grandson Jan Brueghel the Younger followed in his footsteps (restoring to their surname theh that the Elder had abandoned) and helped secure their father’s international reputation. In Brussels, Bruegel produced his greatest paintings and only a few drawings for engravings, as his ties with Hiëronymus Cock had loosened after he left Antwerp.

Toward the end of his career, in addition to numerous landscapes he continued to devote himself to religious stories and scenes of everyday life that made him unique and influential, especially given the historical and political context in which they were created. Bruegel broke away from the iconographic depiction of Catholic saints and martyrs in dissent from the bloody campaigns of the Counter-Reformation: in that mid-1500s the Netherlands became the domain of the Spanish Catholic government, which repressed and persecuted Protestant rebellion. Despite the religious focus of much of his mature work, some art historians suggest that Bruegel was quite aware of the political significance of his work, as recounted by Van Mander himself: not long before his death, the artist asked his wife to burn some of his works, believing that their contents might endanger her.Little is known about the circumstances of his death either, except that since there are no paintings dated in 1569, 1569 was also the last year of his life, at which time, moreover, the Brussels city council exempted him from working with a guard of Spanish soldiers stationed in his home, suggesting that the politically subversive content of his work was precisely well understood. He was buried at Notre-Dame de la Chapelle in Brussels.

Bruegel excelled as a draughtsman, in printmaking and in painting. He was also able to describe the most minute details, in keeping with the Flemish formal and coloristic tradition. His output was extraordinarily broad. Technical mastery enabled the painter to render the vision and atmospheric component of landscapes, such as winter or seascapes, among others, as well as to accurately detail figures. His repertoire consisted of natural scenes in which conventional biblical episodes, parables of Christ, mythological subjects and secular social satires, scenes from peasant life to his “countries of proverbs,” with which he illustrated proverbial sayings and popular everyday life in the Netherlands.From the two engraved series of The Vices (1556-57) and The Virtues (1559-60), to subjects outside the thematic classification such as Struggle between Carnival and Lent (1559) or Children’s Games (1560) and Margaret the Mad (1562), his compositions are allegorically constructed, such that one has to search for content and references to interpret them.

His distinctive stylistic contribution in the history of art was the narrative form of composition whereby the landscape comes alive through the humanity of figures that move and populate the canvases. After his return from Italy, he devoted himself to depictions of crowds of people arranged in such a way as to create several intersecting focal points and usually seen from above. In 1564 and 1565 he drastically reduced the number of figures, making them larger and closer together in a very confined space, later returning to crowds, arranged in densely concentrated groups. This approach distinguishes Bruegel from many Renaissance artists who favored visually more harmonious compositions, in offering instead a portrait of a chaotic and undisciplined human society.

Within the apparent chaos of his large works are men and objects depicted with precise effect and placement. Exemplary of his compositional technique is the painting of Flemish Proverbs (1559), where in the foreshortening of a village Bruegel moves the representative actions of folk wisdom, in those discerned as 120 episodes on folly and vices. Yet another characteristic of Bruegel’s art was his interest in rendering movement. The many paintings of peasant dances are obvious examples, down to the processional representations in The Conversion of St. Paul (1567) where this feeling that appeared in the early drawings of the mountains returns.Toward the end of his life, Bruegel seems to have been fascinated by the problem of the falling figure. His studies reached their zenith in The Parable of the Blind (1568) in which the unity of form, content and expression marks a high point in European art.

His sons carried his style into the 18th century. The younger Pieter would go on to create many copies of his father’s paintings, helping to secure his international reputation long after his death and causing attribution doubts about which were works by the Old Man and which by his son.

Bruegel pioneered what would become known as “genre painting,” choosing to depict ordinary people engaged in everyday scenes of domestic life. In the centuries to come, particularly through the work of seventeenth-century Dutch artists such as Rembrandt, this focus on the context of everyday life would become the basis of Realism in nineteenth-century France and beyond.

In addition to drawings and etchings, 45 authenticated paintings by Bruegel have been preserved, part of a much larger production now lost.The largest number that has come down to us is concentrated between the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, with masterpieces such as the Great Tower of Babel (1563), Hunters in the Snow (1565; read an in-depth study of the work here) or Peasants’ Dance (1568), and the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, which preserves the Fall of Icarus (1558), Fall of Rebel Angels (1562), Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap (1565), and Census of Bethlehem (1566).

Also in Brussels, his house in the Marolles district has been restored and turned into a museum. There is, however, some doubt about the correctness of the identification. Other works are distributed in the world’s most important museums in Europe and the United States, from the National Gallery in London to the Louvre in Paris, the Prado Museum in Madrid as well as the Metropolitan Museum New York. Noteworthy in Rotterdam at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen is the Little Tower of Babel, and in Antwerp the Twelve Proverbs (1558) and Marguerite the Mad (1561), housed at the Mayer Van Den Bergh Museum. As for Italy, Bruegel’s works can be found at the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, where the Parable of the Blind Men and the Misanthrope (1568) are kept, and the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, which houses the Battle in the Port of Naples.

|

| Pieter Bruegel, father of "genre painting". Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.