Piero della Francesca (Borgo Sansepolcro, 1412/1416 - 1492) was called “el monarcha de la pittura” by the great mathematician Luca Pacioli, who was also his friend and who intended with these words to pay homage to the great painter’s stature. Piero della Francesca is one of the pivotal artists of the Italian Renaissance: his painting made of harmony and geometrism, luminous, perspective calibrated on a mathematically set construction, rational, measured in every single detail, has impassioned generations of art lovers.

Although one of the greatest artists of the 15th century, relatively little is known about Piero della Francesca. There are, for example, obscure points about his training: the earliest documents about him date from the early 1430s, after which he is mentioned in a document from 1439, when he was a collaborator of Domenico Veneziano, while in 1445, at the age of thirty-three, he was already commissioned to paint his first major work, namely the Polyptych of Mercy. There are then several works remembered from the sources that have been lost, however, and moreover on several of his paintings the chronology is not certain. He was then an itinerant artist, although he is associated with the cultural climate of Urbino, the city where he stayed between 1469 and 1472: his horizons, however, ranged beyond that.

Piero della Francesca was one of the most influential artists of his time, and his art provided suggestions to many painters of the next generation, some of whom, such as Luca Signorelli and Perugino, were also his direct pupils, while others, such as Antonello da Messina, Giovanni Bellini, Melozzo da Forlì, and Raffaello Sanzio, are nonetheless linked to Piero della Francesca, one of the most important painters in the history of art. For this reason, too, Pacioli considered him the king of painters: in fact, with his definition he had pointed out, Adolfo Venturi wrote, “the great influence of the painter of Borgo on all the Italian art of Emilia and Veneto, southern Tuscany, as well as Umbria, Marche and Romagne, from the court of the Estensi to the workshop of Giambellino, from turreted Cortona to the palace of Federico da Montefeltro, from the Malatesta temple to the Sforza citadel of Forlì and the sanctuary of Loreto.” And from all these lands, “extended the pierfrancescian reform over Rome and Viterbo, over Naples and Messina, from the Vatican palace to the Mazzatosta chapel, from the anonymous frescoes of Monteoliveto in Naples to the renewing painting of Antonello.” Piero della Francesca’s reform is in other words his rigorous and mathematical painting, which would condition the art of several great authors.

Piero di Benedetto de ’ Franceschi was born in Borgo Sansepolcro, today’s Sansepolcro, to Benedetto de’ Franceschi, a merchant, and Romana di Perino da Monterchi. We do not know the exact date, which is somewhere between 1412 and 1416. The curious name by which he is universally known derives perhaps from a peculiar fusion of matronymic and patronymic: since, Vasari explains, Piero’s father died before the child was born, little Piero was identified by his mother’s name, and since Romana was married to a member of the Franceschi family, she herself was known as “la Francesca” (somewhat like the famous Mona Lisa, or Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo, was known as “la Gioconda”). In the 1420s he was in the workshop of Antonio di Anghiari, as certified by a document dated 1430, while in 1432 another document attests Piero’s first commission: the work, however, was not completed. Around 1435 he executed the Madonna and Child in the Alana private collection, the first work by Piero that we know of. In 1438 he left the workshop of Antonio di Anghiari and moved to Arezzo, while the following year Piero was in Florence where he worked with Domenico Veneziano in the chapel of Sant’Egidio in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova. In the same year the Council of Florence took place with the meeting between Pope Eugene IV and the Eastern Emperor John VIII Paleologus: Piero would remember this event when he made the Legend of the True Cross.

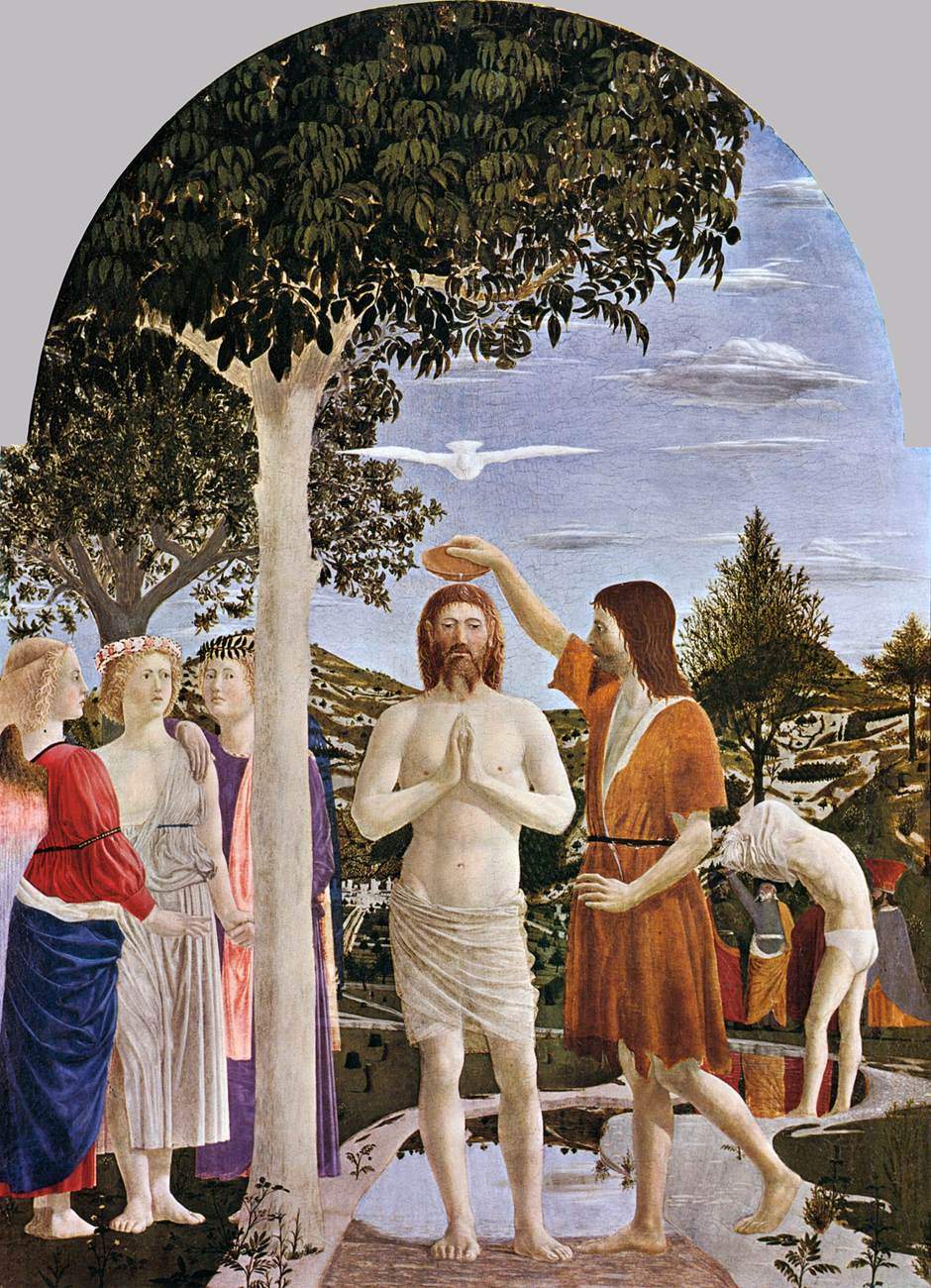

In 1442 the artist returned to Borgo where he opened his workshop, and also around this year he executed the very famous Baptism of Christ now in the National Gallery in London. In 1445, in his hometown, he was commissioned to paint the Polyptych of Mercy. Following much tribulated work the work will not be completed until 1462. Around the same year he is in Ferrara, where he is called by Borso d’Este to execute some works. Later he also makes a brief stay in Rimini. Two years later he travels to the Marches (he stays in Loreto, Urbino and Ancona) after which, in 1450, he executes the St. Jerome, and also around the same year he writes the Liber abaci, his first work as a theorist (he will write three in all): it is a treatise on commercial calculations. In 1451 he was in Rimini where he painted the frescoes of the Malatesta Temple, while the following year represented one of the watersheds in his career: in fact, in 1452, in Arezzo, Bicci di Lorenzo, who years earlier had been commissioned to decorate the choir of the church of San Francesco, died. He was succeeded by Piero, who in seven years painted one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art: the Legend of the True Cross.

Later, in 1458, Piero della Francesca painted the Resurrection of Sansepolcro, and around 1459 he executed the Magdalene in the Cathedral of Arezzo. After finishing the Legend of the True Cross, Piero moved to Rome where he did some (lost) works for Pius II. However, he is reached by the news of his mother’s disappearance and returns to Borgo. He will never return to Rome. In 1464 he was back in Arezzo, and around this year he executed theHercules, his only known work on a secular subject. In 1468 he finished the Perugia Polyptych, and the following year he returned to Urbino, called by Federico di Montefeltro, who commissioned some of his most famous works. Around 1472 he executed the portraits of the dukes of Urbino preserved in the Uffizi, while in 1474 he finished the Montefeltro Altarpiece currently in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. The Madonna of Senigallia dates from around 1478(read an in-depth study of the work here). In 1479 he returned to Borgo San Sepolcro: few paintings remain to us of his production in the following years. His most famous treatise, De prospectiva pingendi, devoted to perspective, dates from about 1480, while around 1481 he executed the Nativity preserved at the National Gallery in London. In 1482 he was in Rimini where he wrote, finishing it in 1485, De quinque corporibus regularibus, a treatise on Euclidean geometry. Of his last years of activity we know very little: his will dates from 1487, while on October 12, 1492, he died in Borgo Sansepolcro, being buried in the Badia.

Piero della Francesca works in the midst of a humanist climate, with art that responds to the anthropocentric view of the world that was spreading in Italy in the 15th century: intellectuals were beginning to discover and apply the laws that govern nature (and consequently to discover its beauty). Mathematics thus becomes a fundamental science not only for the study of natural laws, but also for art. Piero della Francesca, moreover, pours his passion for mathematics into his treatises as well as into his art. His painting blends the volumetries of Masaccio, the perspective rigor of Paolo Uccello, and the luminous color of Domenico Veneziano. Unfortunately, we are left with no early works by Piero della Francesca: his earliest known work is in fact a Madonna and Child, a painting that was recently found but is of uncertain date (it could date from between 1435 and 1440). From this painting, however, we can discern some distinctive features of his art: theimpassivity of the characters, therigorous perspective layout, and the geometrism that governs the entire composition (incidentally, on the verso of this painting there is a realization in perspective, almost an exercise of the artist).

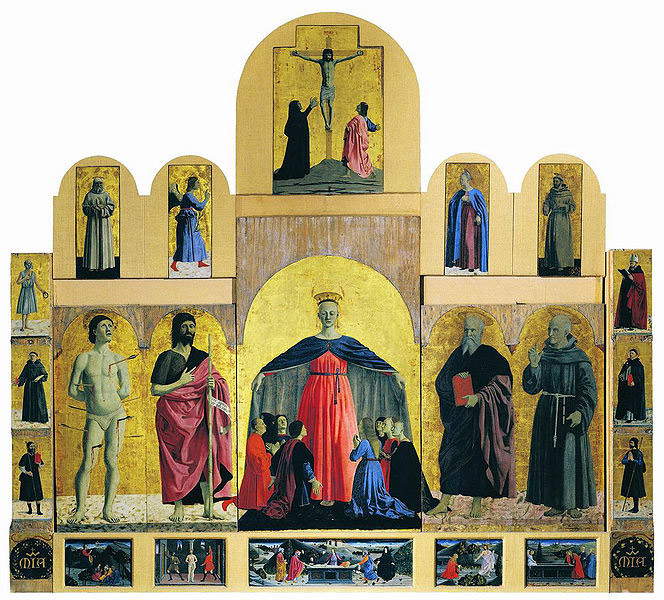

The first work of which we have documentation is instead the famous Polyptych of Mercy: the commission dates from 1445. We see the main figures painted on the gold background typical of medieval polyptychs, although the plasticism of the bodies of the saints is typically Renaissance (the gold background may have been a concession to an out-of-date clientele). Our Lady of Mercy in the center offers her protection to the members of the confraternity, while on either side of the main figure are depicted Saint Sebastian, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Benedict of Norcia, and Saint Francisco. Again, the cymatium depicts a Crucifixion that is almost a kind of tribute to Masaccio’s Crucifixion from the Pisa Polyptych, which is currently in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples. In this painting, too, we notice many typical features of Piero della Francesca’s art: careful perspective setting, geometric simplification of the figures, bright colors.

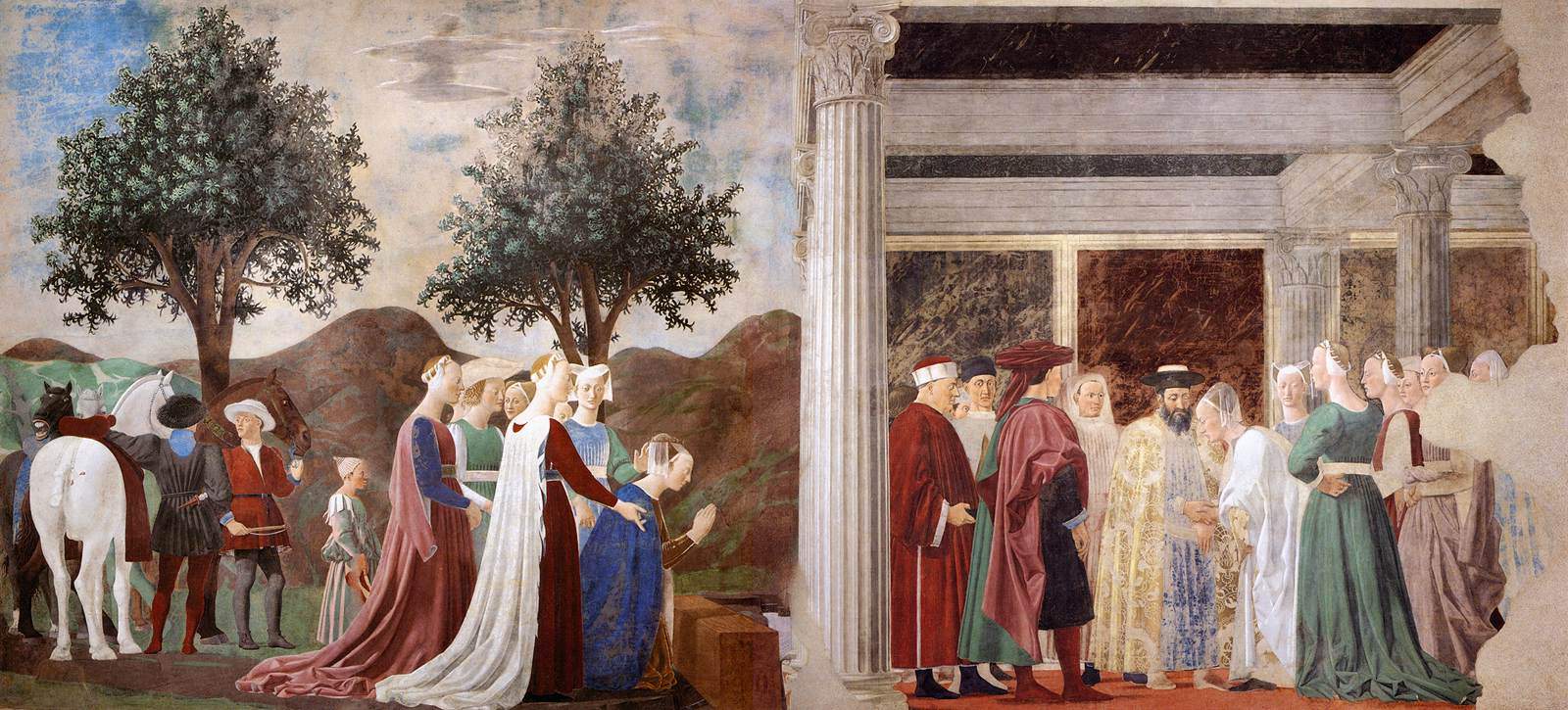

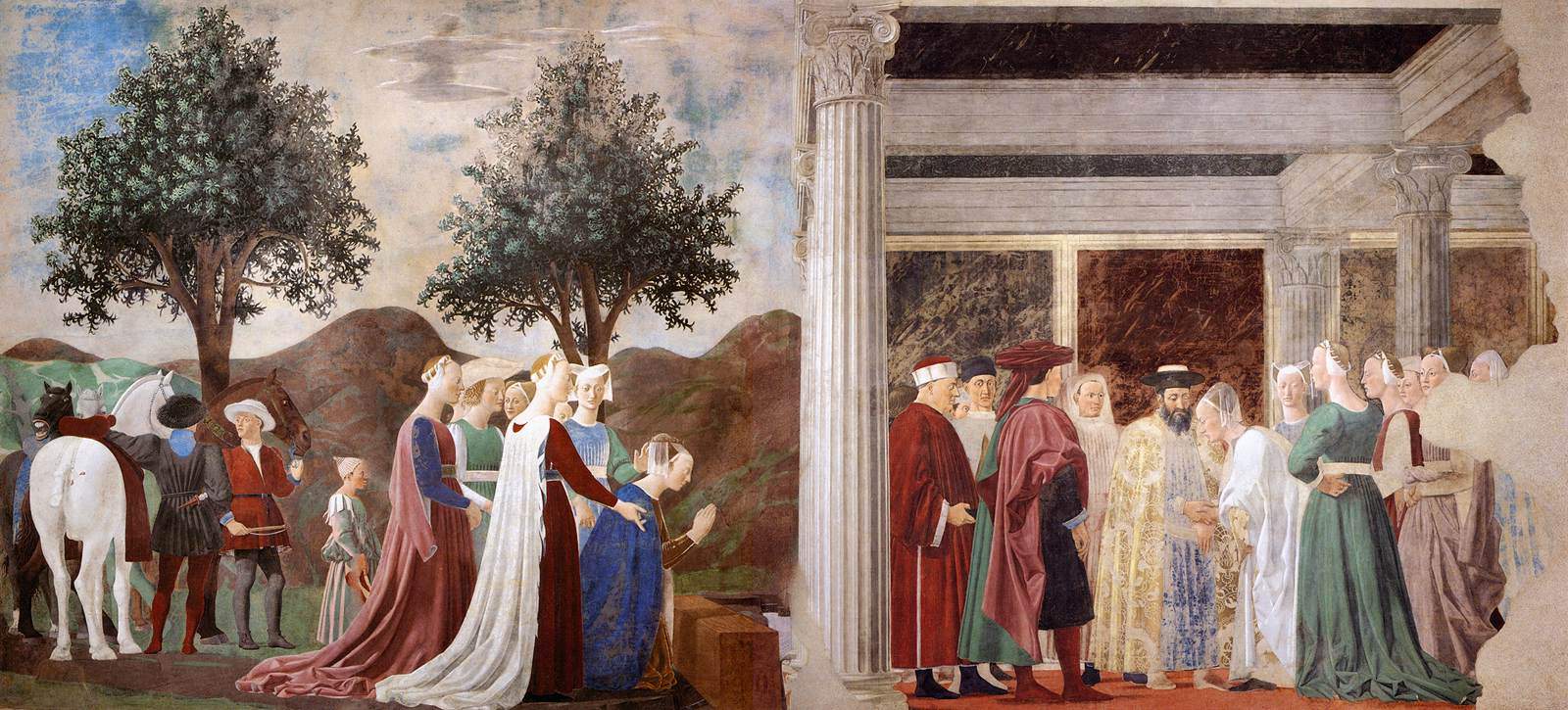

A little later is the Legend of the True Cross, the cycle of frescoes decorating the Bacci Chapel in the church of San Francesco in Arezzo. It is a work where history, legend and even current events coexist. In 1439, in fact, the Council of Ferrara and Florence had been held, attended by Pope Eugene IV and the Eastern Emperor, John Paleologus. The purpose of the council was to bring the Eastern and Western churches closer together against the threat of the Turks, who were pressing in and would shortly end up conquering Constantinople (in fact, in 1453 the city, the capital of the Eastern Empire, finally fell). The themes of the 1439 Council are then further taken up in 1459 at the Council of Mantua: the frescoes could thus be read as a sort of invitation to John Palaeologus to take up arms against the Turks in order to protect one of the bulwarks of Christendom. The cycle in fact consists of ten frescoes that narrate the Legend of the True Cross, which tells the story of the cross on which Jesus was crucified (it is taken from Legenda aurea written by Jacopo da Varazze, a monk who lived in the 13th century). The scenes are arranged not in chronological order but in thematic order. The chronological order, however, would like the reading to begin with the scene with the death of Adam, and then continue with the meeting between the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon (the queen, on her journey, finds herself in front of a small bridge made from the wood of the tree of good and evil, from which the material from which the cross of Christ will be made will be derived). The queen senses the sacredness of wood and before crossing it she kneels in worship. We then move on to the third episode, the burying of the wood: Solomon in fact senses that that wood will be a cause of misfortune of suffering for the Jewish people and decides to have it buried. The fourth episode is the Annunciation, after which we then come to the fifth, which also represents one of the earliest nocturnes in the history of Italian art (although it still takes place at the crack of dawn): it is the Dream of Constantine, during which an angel comes to Emperor Constantine on the eve of the battle between him and Maxentius and announces to him that under the sign of the cross he will win the battle. The sixth episode is precisely that of the battle between Constantine and Maxentius (Constantine is, moreover, depicted with the features of John Paleologus: it should also be noted that the soldiers were depicted dressed in headdresses with oriental fashions, inspired by the paintings of Pisanello, who had been the only artist allowed to follow the Council of Ferrara and Florence). The seventh episode is that of the torture of the Jews at the well: Helena, Constantine’s mother, knew that some of the Jews were aware of the place where Jesus’ cross was buried, so she has them subjected to this torture in order to have the site revealed. The cross is finally found in the eighth episode, and in the ninth episode the Persian emperor Cosroes steals the cross, so Heraclius, emperor of the East, sets out to retrieve it and defeats the Persian king in battle.

It is one of the finest fresco cycles of the 15th century, with essays of virtuosity (the luminism of Constantine’s Dream), intense action (the battle scenes), eloquent gestures, and rigorous patterns. A painting that would foster the encounter between Piero della Francesca and the Montefeltro court, where the artist would have the opportunity to bring to completion some of his most important works, including the portraits of the dukes of Urbino, namely Federico da Montefeltro and his wife Battista Sforza, which are now preserved in the Uffizi in Florence, and the Montefeltro altarpiece preserved instead in the Brera picture gallery. The Montefeltro altarpiece is a “sacred conversation” in which the Madonna takes on the features of Federico da Montefeltro’s wife (portrayed kneeling with clasped hands, in adoration), namely Battista Sforza, and the baby Jesus, on the other hand, is none other than Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, the couple’s son. The painting is notable for its study of architecture, light (the reflections on Federico da Montefeltro’s armor are remarkable, suggesting a circular light, thus hinting at the egg that hangs above the figures), and again for the geometric simplification of the figures, so much so that this work is considered a kind of synthesis of Piero’s art. The egg that is at the center of this imposing architecture is a symbol of the Immaculate Conception, thus a symbol of the Virgin Mary, and it is also the pivot of Piero’s theological reflection: the idea of placing the Madonna and Child in a church was in fact of Flemish origin, and the purpose was to express the identification between Mary and the Church. Traditional iconography, however, required the Madonna to have very large, unnatural proportions. Piero della Francesca, by inserting the symbol of the egg, could propose to the patron an image that was nonetheless effective without sacrificing natural proportions. The Montefeltro altarpiece, a complex work, is a fundamental junction in Italian art, the summa of Piero della Francesca’s art, and would later be the basis for reflections by great artists such as Giovanni Bellini and Antonello da Messina, both of whom are indebted to Piero della Francesca’s spatial conception.

Few of Piero della Francesca’s works remain with us, and they are all scattered around the world, although most are in Italy. The largest nucleus of the artist’s works is in and around Arezzo: so we start in the capital, where we admire The Legend of the True Cross in San Francesco and Mary Magdalene in the Duomo, and move on to Sansepolcro to see the Polyptych of Mercy, the Resurrection, the Saint Julian and the Saint Louis of Toulouse at the Museo Civico (it is the museum with the most works by Piero in the world: no other holds more than three, if you except for parts of the dismembered Polyptych of St. Augustine, four of which are at the Frick Collection in New York), then to Monterchi for the Madonna del Parto in the museum dedicated to her in the town. Also in Tuscany, the Uffizi in Florence holds the Portraits of the Dukes of Urbino. At the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino are the Flagellation and the Madonna of Senigallia, while the Malatesta Temple in Rimini holds the famous fresco of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta praying before St. Sigismund. Still, in Venice, the Gallerie dell’Accademia holds the San Girolamo and the donor Girolamo Amadi, in Perugia the Polittico di sant’Antonio at the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria is observed, while the PInacoteca di Brera in Milan holds the Pala Montefeltro.

Abroad, works by Piero della Francesca can be found at the National Gallery in London (the Baptism of Christ, the Nativity and a panel from the predella of the lost polyptych of St. Augustine), the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (the Penitent Saint Jerome), the Louvre (the Portrait of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta) and the Isabella Stewart-Gardner Museum in Boston (theHercules).

|

| Piero della Francesca, the rational painter of the Renaissance: life and works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.