Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) was an artistic trend that emerged widely in Germany in the 1920s as a reaction to Expressionism and abstraction, in favor of a return to objectivity of representation. It developed at the end of World War I as a multifaceted, predominantly pictorial phenomenon, establishing itself in the cultural climate of the Weimar Republic until the advent of Hitler’s Nazism in 1933. Against the over-emotionality of their German Expressionist colleagues, who had revolutionized the canonical composition of the painting and used color to express intense personal emotional charge, the New Objectivity painters returned to realism, to theinterpretation of the world in its rawest terms, though not in a descriptive and impersonal or canonical manner, carrying on an analysis and narrative of German society after World War I. The New Objectivity, however, differed from realism in that it retained a certain emotional component, typical of Germany’s cultural tradition.

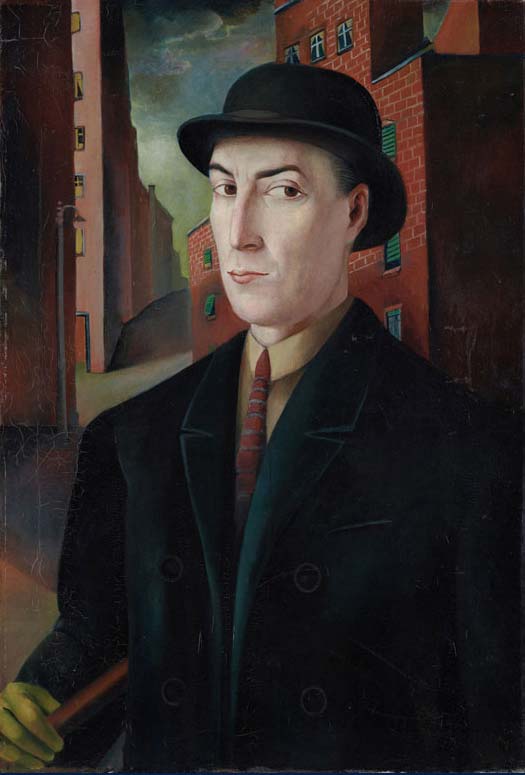

The artists who were members of this group were committed to representing current events, asserting various and different inclinations and styles, and the attitude of reevaluation of the objective datum took the form, for the most part, not of traditional mimicry, but of realistic if distorted and dark visions that aimed to expose the moral degradation and tangible conditions that each person witnessed in his or her own way. Their styles ranged from a satirical verism to a nostalgic classicism to a disturbing realism later termed “magical,” and despite their differences, they predominantly preferred static compositions with precisely delineated subjects, thus eliminating the presence in the painting of traces of the pictorial process or any irrational gestural elements.

The official consecration of this trend came with a major exhibition at the Mannheim Kunsthalle, organized in 1925 by the institution’s first director Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub (Bremen, 1884 - Heidelberg, 1963), which helped to the emergence of such exponents as Otto Dix (Gera, 1891 - Singe, 1969), George Grosz (Berlin, 1893 -1959), Georg Scholz (Wolfenbüttel, 1890 - Waldkirch, 1945), Max Beckmann (Leipzig, 1884 - New York, 1950), Alexander Kanoldt (Karlsruhe, 1881 - Berlin, 1939) and Georg Schrimpf (Munich, 1889 - Berlin, 1938), among others. It established a “cold” painting that denied all sentimentality and spiritualism and addressed the consequences of war, the relationship with sexuality and money in society, the dramatic incumbency of the machine in human life, and the illusions and contradictions of existence. From the body of works that survived the Nazi censorship of the 1930s, there emerges the social and political turmoil of those years, the rise of cities into metropolises, with the assertion of a certain sexual freedom and customs, as well as the growing alienation of the individual increasingly distant from nature and rural life.

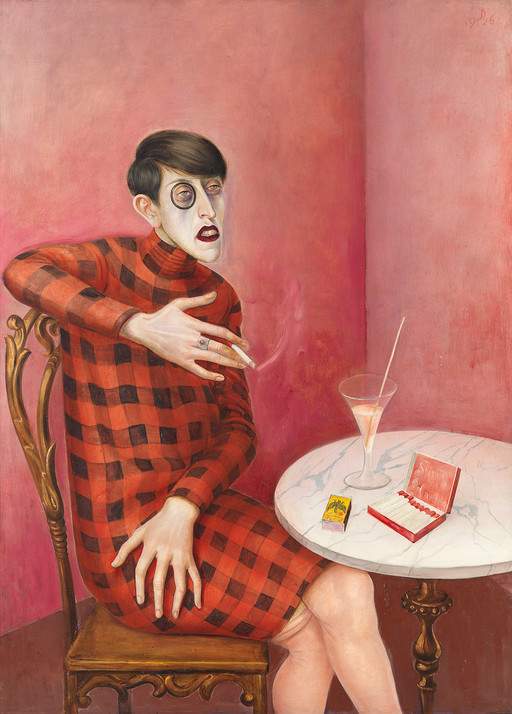

Within the group, a veristic current, especially in Berlin and Dresden, and a classical current, in the art centers of Munich and Karlsruhe, became established. Some such as Dix and Grosz used the tools of satire with merciless irony on the world, others manifested a more emotional vein, such as Kanoldt and Schrimpf or a personal idealizing version of objects, for all that was disturbing and ambiguous in them. The genre in common among them was portraiture and self-portraiture, and in their effort to paint the truth of the person, the works of the New Objectivity can be recognized by the unflattering details or disturbing psychological effects of the characters portrayed, such as political leaders and bureaucrats, workers and bohemian charactersmien, including those called the "profiteers" of the war, beggars and prostitutes, and of course themselves, each complicit in the society in which they lived.

In the years before World War I, theExpressionism of the Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter groups dominated in Germany, inspired by the exoticism of non-Western art and the dynamism of modern, urban life. These Expressionist artists had abandoned traditional conceptions of art, seeking a highly personal and emotional language, focusing on the inner world of the individual through color, and emphasizing a subjective perspective of understanding the world. If the idealism of Expressionism reigned before the war, the more conceptual Dadaism, founded in 1916 in Zurich and soon after spreading to Berlin, embodied the nihilism and anti-artistic sentiment of many artists during the war.

It was to be in the period leading up to the establishment of Germany’s first democratic government in 1918 that an early desire for a return to the objective fact was manifested by artists scarred by wartime devastation, social upheaval and economic hardship. Named Novembergruppe, after the month of the revolution that led to the establishment of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933), the large group that gathered around founding painters Max Pechstein (Zwicau, 1881 - Berlin, 1955) and César Klein (Hamburg, 1876 - Ratekau, 1954), rejected the sentimentalism of prewar German expressionism, preferring a more realistic and sober view of life, in affirming a possible renewal of society and art in the political terms of socialism. The inclination of many artists was toward the harshness of the reality of many cities and of everyone’s everyday life, which without disguise or elaboration was represented in works that acquired the value of testimonies.

In 1922 painters such as Otto Dix and George Grosz distinguished themselves by a practice all about this new realism. Having both participated in the beginnings of German Conceptual Dadaism, and having later distanced themselves from it, they turned to an incisive and brash mode of painting that highlighted the effects of war and corruption in an uncompassionate manner. The term "Neue Sachlichkeit,“ translated as ”New Objectivity," was first coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, art historian and director of the Mannheim Kunsthalle, as the title for an exhibition that was initially scheduled to open in 1923 but opened in 1925.

The exhibition examined the post-expressionist work of various artists with different stylistic approaches, including precisely Dix and Grosz, Georg Scholz and Max Beckmann, Alexander Kanoldt and Georg Schrimpf, as well as Rudolf Schlichter (Calw, 1890 - Munich, 1955), Carlo Mense (Rheine, 1886 - Königswinter, 1965) and Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (Aachen, 1894 - Nice, 1970), to name the most representative. With the exhibition, Hartlaub set out to document the new objective pictorial trend that was taking place, and of which he recognized two undercurrents or “wings”: one " left-wing,“ derived from Dadaism, critical and ironic toward the bourgeois society of the time; one ”right-wing," characterized by a return to the plasticity of form in reference to classicism.

As much as some tended toward “cynicism and resignation,” in recognizing these explicit directions within the group, Hartlaub observed that the body of work expressed “enthusiasm for immediate reality as the result of a desire to take things entirely objectively, on a material basis, without investing them with ideal implications.” All the artists had focused on as objective a representation of their time as possible, aimed at “tangible reality.” The initiative to bring them together in Mannheim was successful, finding favor with Weimar intellectuals who appreciated their rejection of romantic and idealistic aspirations. Germany’s first democracy aimed to reinvigorate and redefine the nation with a new political and economic approach, however, life in the Weimar Republic was marked by an economic malaise that was defining a generalized climate of continuous malaise, where prostitutes, beggars and general degradation were predominant throughout the nation, becoming part of the repertoire of these artists.

The 1925 exhibition, the title of which has remained to define the trend as a whole ever since, passed through several cities, and the group became quite popular and influential in the following years. Although geographically dispersed throughout Germany and stylistically diverse, the Neue Sachlichkeit artists shared the same skeptical perception about the direction of the country. Deeply disillusioned, their subjects and themes echoed their concerns. Otto Dix explained that they "wanted to see things completely naked, clearly, almost without art." The advent of Nazism, however, interrupted their exhibitions, six of which had been held from 1925 to 1933: the most important, with the one in Mannheim, had been the exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1929.

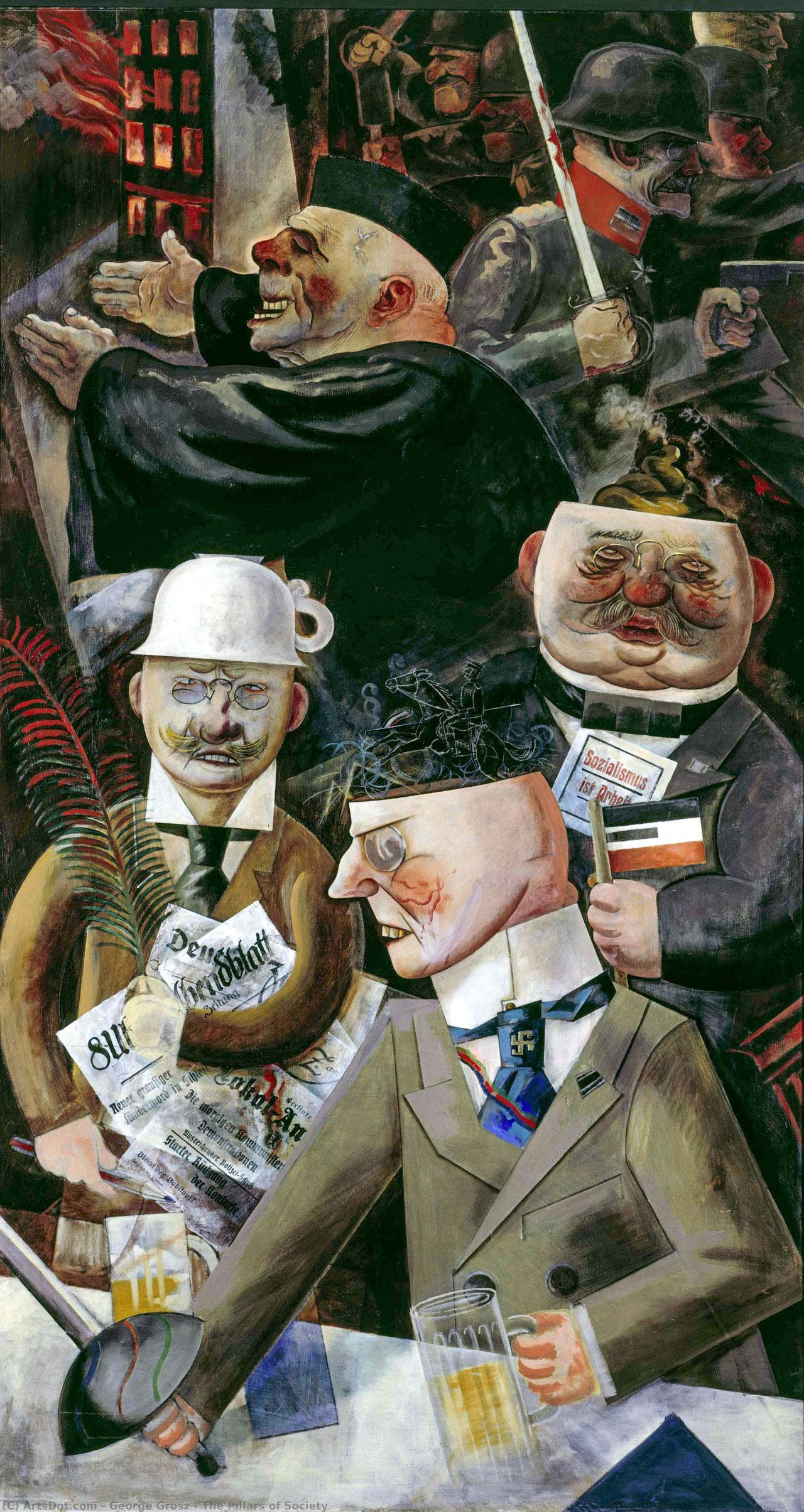

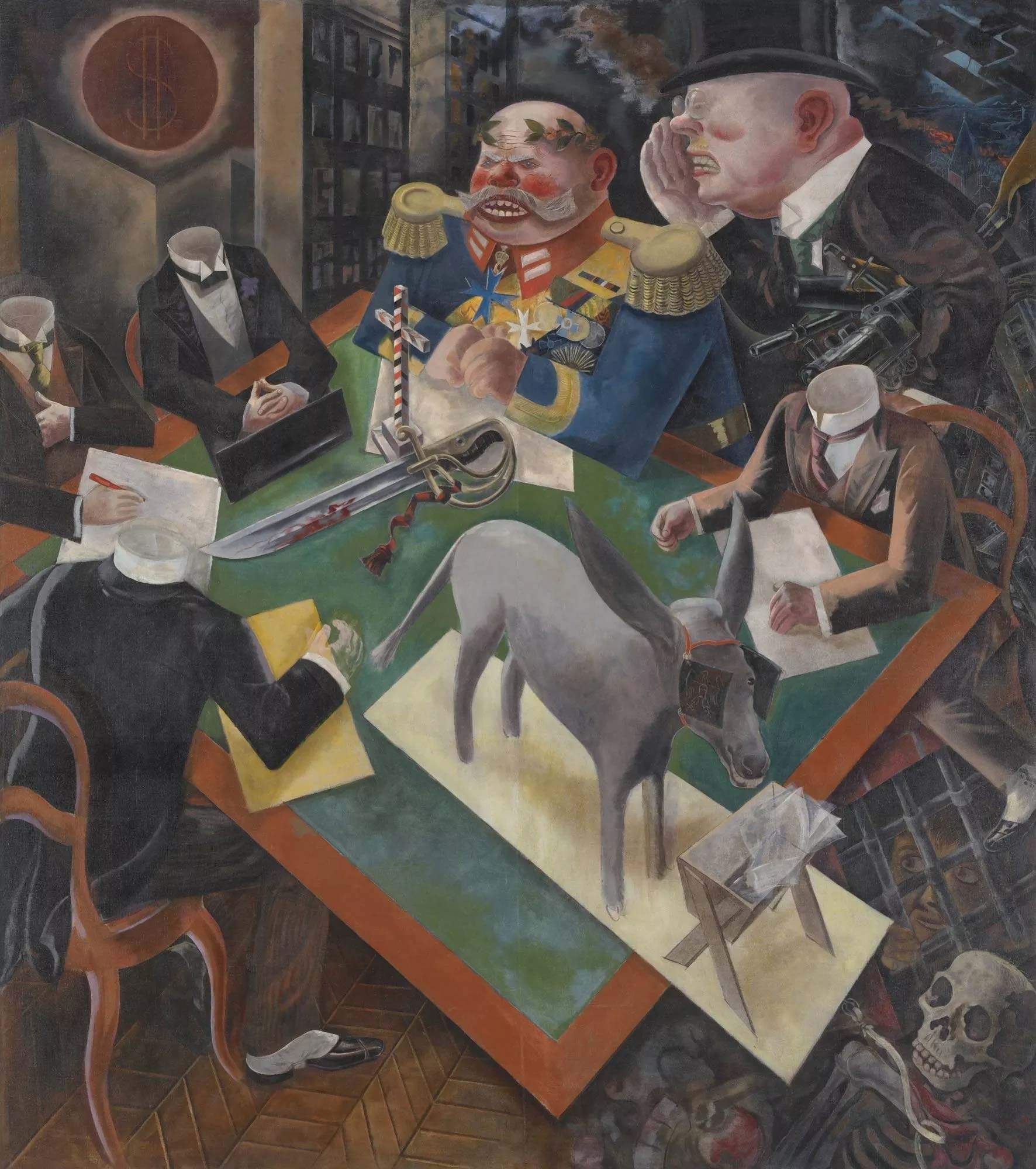

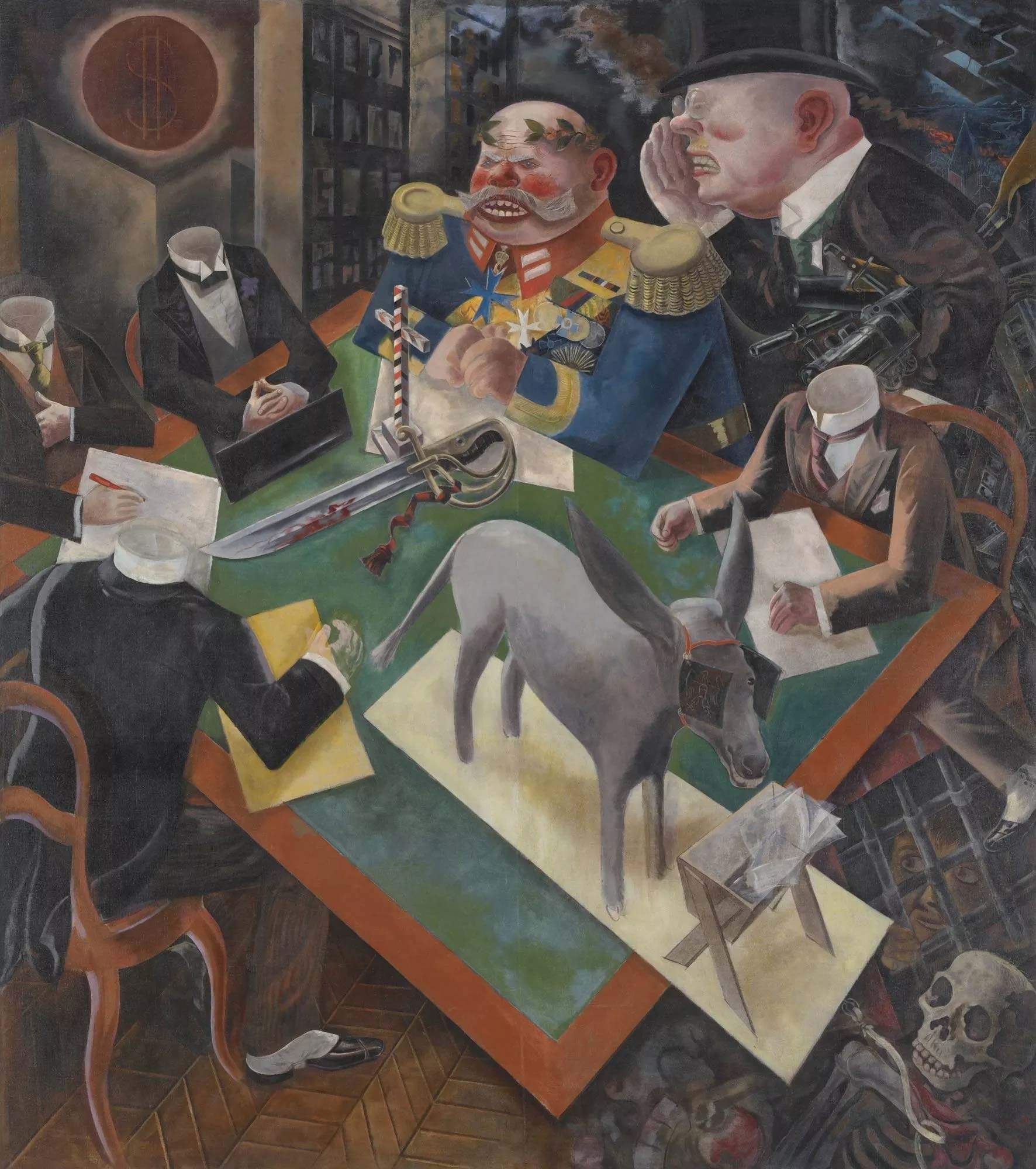

Hartlaub along with other scholars had identified two dominant stylistic approaches among the New Objectivity artists: the left wing, which included Dix and Grosz, came to be called the "Verists," who defined a form of realism that favored contemporary subjects with an underlying political commentary. Caricatured, grotesque and partly shocking exaggerations of realistic characters were placed in unnatural, cold and sharp perspectives, constituting a denunciation of the difficult conditions of the time during the Weimar Republic. Important examples include George Grosz’s works The Pillars of Society or Eclipse of the Sun of 1926, among others.

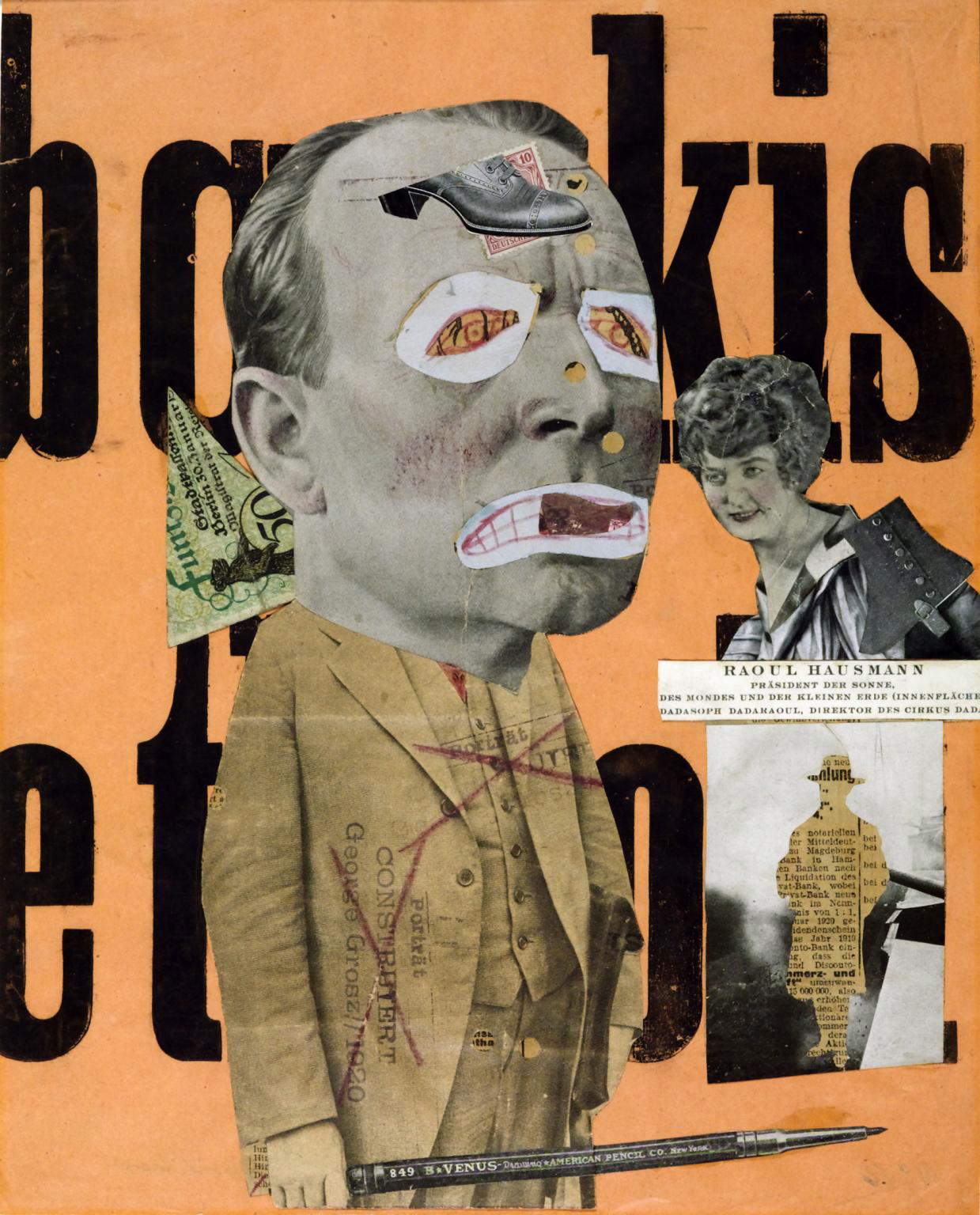

Painters of the verist branch also include Beckmann along with Schlichter and others, whose works are united by their harsh and highly polemical attitude toward society, bourgeois culture and power. Among them were also some photographers, such as the Austrian Raoul Hausmann (Vienna, 1886 - Limoges, 1971), who contributed to the spread of the photomontage genre(The Art Critic, 1920). In tandem with Dadaism’s conception, art was not to adhere to specific rules or languages but to be open to exuberant compositions that allowed an escape from pessimistic general inclinations. Indeed, the Verists of the New Objectivity asserted a form of “satirical hyperrealism,” a term used by Hausmann himself, which emphasized the ugly and crude in a provocative way.

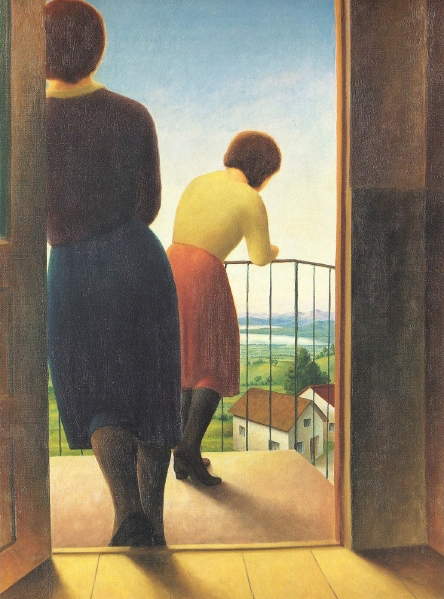

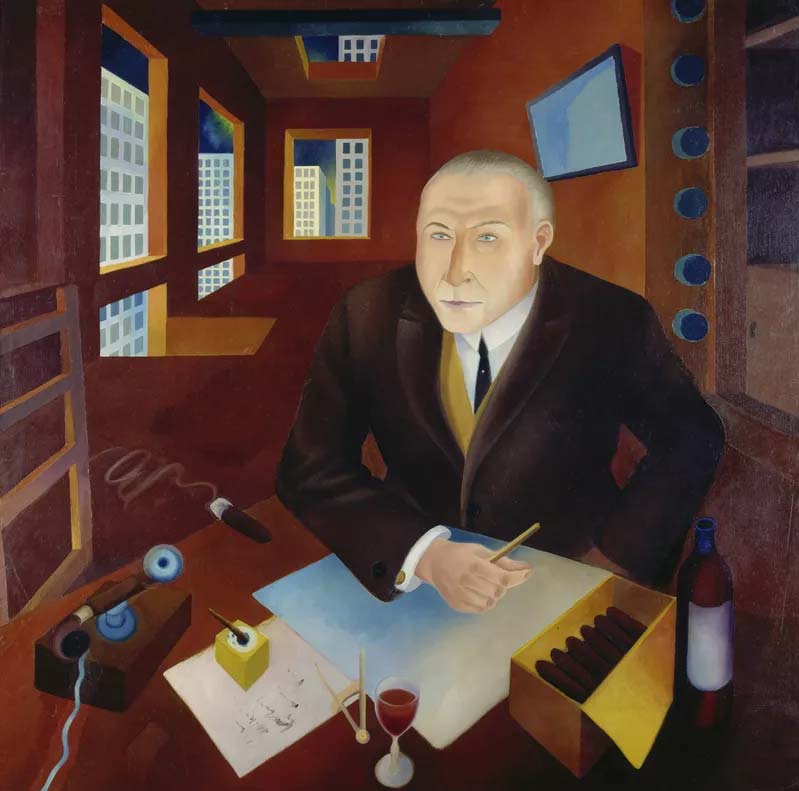

Hartlaub’s right wing, known as the "Classicists," on the other hand, rooted itself in the more classical conception of art, seeking a universal pictorial language and proclaiming a "return to order," which was later common throughout Europe during the interwar years. The group drew inspiration from the researches of Italian Metaphysical painters such as Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico, who were advancing an anti-modernist creed, of recalling, precisely, order and tradition. The Classicists developed a stylistic orientation that was often described as “cold” and “static” and mostly avoided the social issues that were so central to the Veristi. Significant to this current were Schrimpf’s portraits, with quiet, monumental figures as in Portrait of a Child (Peter in Sicily) of 1925 or At the Balcony of 1927, or Davringhausen’s interior scenes(The Profiteer, 1920-1921), as much as Kanoldt’s still lifes and landscapes.

In 1925 this undercurrent was renamed "MagischerRealismus" ("Magic Realism") by art critic Franz Roh, a term that came to describe the approach that combined an “objective” idea of life with surreal or mysterious qualities. Overall, these works emphasized a profound accuracy of technique with an elusive “magical” content that described novel relationships with characters, landscapes and objects. At the same historical moment, in 1924, Surrealism was born, which endowed the world of forms with new potential, the more unusual the more familiar the motifs depicted. Such a highly complex post-World War I climate explains why various nuances were so important in the works of the New Objectivity.

As we have seen, the genre of the portrait and self-portrait was in common between the two opposing currents: the closest resemblance to the model was sought (Otto Dix, Portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden, 1926), captured either within a rarefied space (Carlo Mense, Portrait of Davringhausen, 1922), or in the place of his activity professional (Otto Dix, The Physician, 1921), and so, given the spectrum of personal styles and techniques, New Objectivity paintings included from hyper-realistic portraits to vicious caricatures of corrupt individuals, as in Georg Scholz’s ruthless depictions.

There were favorite themes (lovers, card players, the working-class world, the devouring industrial landscape of urban agglomerations) that to this day provide a panorama of social life in the 1920s after the Great War. Compared to the predecessors of Expressionism, these artists gave color a different role, no longer so totalizing but dependent on drawing, which became very analytical again, responding to their historical moment with a search for objectivity in all areas of life. Although many of these protagonists of the New Objectivity continued to work in their representational styles after 1930, in its last evolutionary stages this trend turned toward an increasingly precise and detached objectivism, in which the premises of the photographic verism of official Nazi art were seen.

|

| Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity. Origins, development, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.