Minimalism, history and artists of the reductionist movement

Minimalism, or Minimal Art, was one of the most important experiences that matured in the art world in the mid-1960s. One can consider this trend as the first statement of an American sculpture that was composed of mute objects, presenting itself with a neutral ideology. The impersonality of the minimal artist was identical to that of the pop painter who chose any stereotype of the civilization around him and displayed it as the object of his work itself. Along with pop art, in fact, Minimalism was the major American art current of the 1960s, consecrated by the Primary Structures exhibition in 1966.

The main protagonists worked in the early years of the decade: Donald Judd (Excelsior Springs, 1928 - Manhattan, 1994), Robert Morris (Kansas City, 1931 - Kingston, 2018), Carl Andre (Quincy, 1935 - Manhattan, 2024), Dan Flavin (Jamaica, 1933 - Riverhead, 1996) and Sol LeWitt (Hartford, 1928 - New York, 2007). Distinguished in the field of painting was Frank Stella (Malden, 1936 - New York, 2024) who declared the significance of his pictorial operations, “My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there. It is really an object. [...] All I want others to get out of my paintings, and all I have ever taken from them, is the fact that you can see the whole compositional idea without confusion [...] What you see is what you see.” (from Bruce Glaser’s interview, Questions to Stella and Judd, in “Art News,” September 1966).

History of Minimalist Art

The label Minimalism defines those artistic trends characterized by a reductionist essence. They are radical experiences aimed at identifying pure primary physicality and the basilarity of structures, surfaces, and color interventions. The group of minimal artists took shape around the 1960s and was recognized in an exhibition, Primary Structures, which was mounted at the Jewish Museum, New York, in 1966. The common characteristics of the members of this fellowship were an interest in objecthood, fundamental, plastic and three-dimensional structures. These artists sought a strong simplification of forms, a solid and impersonal rationality of an artistic language that also had the function of preventing any incursion related to the emotional sphere of the author.

Minimalist works can be geometric solids, metal structures made from semi-finished or prefabricated industrial materials; they are works that have a strong spatial connotation, a specific relationship with the place that contains them. Often the forms are repeated in series or modules, with colors proper to the same materials or reduced strictly to the black and white range.

The definition of Minimal Art was the one first outlined by British critic Richard Wolheim(Minimal Art, “Art Magazine,” January 1965), who spoke of minimal reduction of artistic content in reference to 20th-century works characterized by an increasingly decisive move away from traditional manual labor, such as in the case of Duchampian ready-mades. Since minimalism was primarily an American experience, the philosopher called into question the works of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, but he also arrived at the blank page of the French symbolist poet Stephane Mallarmé. Among the models and masters that can be identified is certainly the lesson of the artist Marcel Duchamp, but also that of Ad Reinhardt who, with his invisible black-and-blue works, was one of the inspirers of the artists of minimalist research. A key precursor was the work of Kazimir Malevic, his Black Square on a White Ground with its extreme simplification, as early as 1915.

Among the sources pertinent to the field of sculpture, the contribution of Russian Constructivism is incisive: the Constructivist works were composed of materials chosen for their specific qualities and were placed in the space of everyday reality, as happened with Vladimir Tatlin’s Reliefs, to which the minimal artist Dan Flavin later paid homage. Considered to be the initiator of the Minimalist trend was the American painter Frank Stella with his Balck Paintings, the totally black paintings whose physicality is etched by very thin lines that animate their surface, according to geometric movements that reset any emotional throb.

In the 1960s Minimalism opposed the subjectivity ofAbstract Expressionism, whose impetus it replaces with an attitude of cold vibration and rigorous essentiality. The creative act, which the Expressionist artist understood as a free outlet for his drives and emotions, was then devoted to the impersonality and dry immanent physicality of the work. Nevertheless, minimalists considered the value of the works and novelties introduced by Jackson Pollock and colleagues. The large-scale work, conceived as a visually striking whole, remained a recognized and foundational element of what was the specifically American artistic vision, to be contrasted with the more traditional European one, still tied to the aura of the work to be contemplated, seeking to bring its meaning as close as possible by following a motion of depth.

![Robert Morris, L-Beams (1965 [1970]; stainless steel; New York, Whitney Museum) Robert Morris, L-Beams (1965 [1970]; stainless steel; New York, Whitney Museum)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/fn/robert-morris-l-beams.jpg)

Main Artists of Minimal Art

Minimalist artists acted moving compactly around the mid-1960s. They initiated an investigation between 1963 and 1964 by following common and clearly recognizable elements in each artist. In general, all minimalists insisted on geometric volumes, together with primary elementary forms, trying to reduce as much as possible - to an essential minimum - the value given to manual intervention. Very often it is the moment of the choice of material that is of crucial importance, both for the organization of the composition of the work and for its unfolding. The color, in sculpture works, is the natural, original color of the material used. The object counts as an element proposed for interaction with the surrounding space. Some objects and installations had to be mounted in a specific place: when the work is made for a specific space, a formula is used that is still valid today, namely that of site specific. With this mode, the works converse more with the environment than as works in themselves.

Donald Judd, a philosophy graduate, began as a painter in the mid-20th century and then worked with a number of magazines as an art critic, “Art News” and “Arts Magazine,” from 1959 to 1965. He made works that consisted of "stacked" geometric structures. They are regular, sharp objects, displayed in strict relationship to the space that may be a gallery or a museum. Compared to the other minimalists, Judd was the coldest and most rigorous. He used industrial-type materials such as stainless steel, anodized aluminum, and Plexiglas. His choice fell on three-dimensional and elemental structures, materials related to the specific identity of the work: color, forms and surface were thought to concentrate all the focus on objectuality.

Because of the minimalist concept that manual labor must be eliminated, Judd proceeded with industrial techniques and machinery in order to ensure maximum precision and impersonality in execution.

For the 1963 exhibition at the Green Gallery in New York he exhibited a series of reliefs and structures in wood or other materials, all colored in cadmium red. In Untitled (1963) light cadmium red oil paint covers a wooden parallelepiped, which was machined, measured according to the artist’s design. One face is pierced by a tubular opening, forming a kind of channel that creates a passage; even before it is a sculpture, in Judd it counts as an object. Manual dexterity is absolutely denied: from the application of color to the clean cuts in the wood, the object guarantees that it has not been in physical contact with the artist.

In later years, the artist began to work with metals, producing the boxes in iron or aluminum, placing them either as single elements or in his stacked forms, series that develop as a whole. Untitled (Stack) of 1968 is one such work of cool technical execution, of rigorous and articulated scanning of solids and voids but constituting a unified whole. Judd set aside the idea to sublimate the objective, physical and concrete character: this remained the true aesthetic essence and sole content of his works.

In the groove of full materialism Carl Andre also moved: the formal identity of his works coincided with that of the industrial and prefabricated elements used, common materials. Andre combined these forms in an elemental sense, so as to cancel any distance between artistic operation and common intervention. The goal of his creations was to create the conditions to allow a renewed perception of the primary building elements, playing on their physical presence and environmental placement. In doing so, he redefined the meaning of sculpture, reflecting on the fundamentals of verticality and horizontality, weight and space. Hour Rose is a painted wood, very rigorously shaped and worked through machinery that distances the idea of human intervention, the spontaneity of craftsmanship. Andre began experimenting with the utmost essentiality of form with his “sculpture-floors” from 1968. The following year is dated 144 Lead Square, a site-specific work. Using square slabs, the sculpture is characterized by its floorness (paving), as a pure space-place where the viewer can walk and enjoy a direct and unprecedented sensory experience.

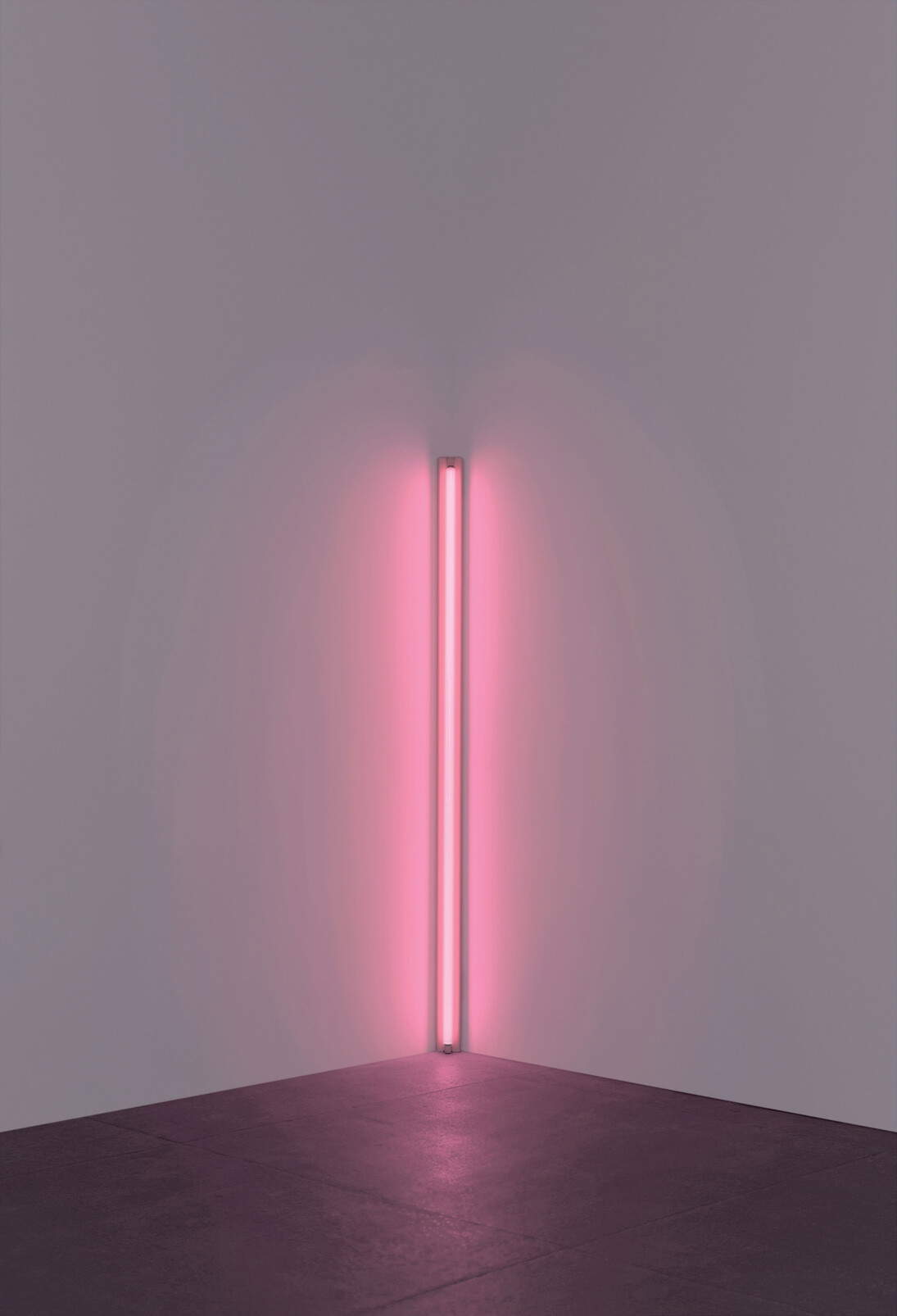

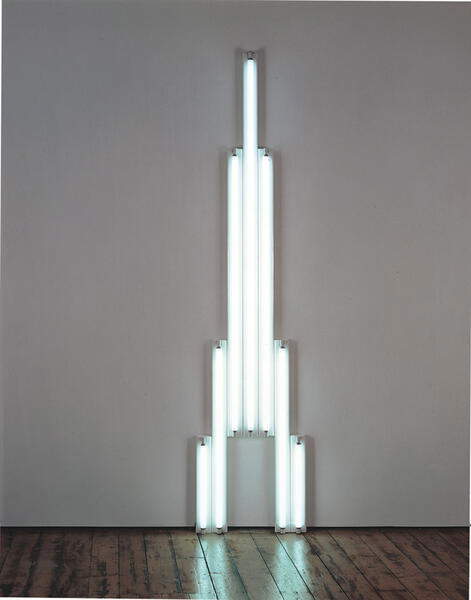

Dan Flavin worked in the field of Minimalism beginning in the 1960s. His work was distinguished by his interest in light and the strong importance given to it in Minimalism: initially with the work Pink out of a corner in 1963, where a simple object, a pink neon tube was placed in the corner of a room, becoming the basic module of all his fluorescent works. By turning on the light tubes, Flavin gave new meaning to the space, initially seeing a spiritual dimension in the luminous radiance of his works. Gradually, Flavin came into contact with the work of artists such as Vladimir Tatlin, Jasper Johns, and Frank Stella, coming to conceive and share the value given to objects, that is, as true physical phenomena. It was precisely to Tatlin, and his Monument to the Third International Project, that Flavin dedicated a cycle of works, Monument for Tatlin (1964-1982), consisting of installations of scalar combinations of neon of various sizes, expanding a cool white, yellow and red luminosity in space.

An absolute leader of minimalist sculpture was Robert Morris. The artist reasoned about minimalist problematics focused on the relationship between object, space and viewer, but the Duchampian conceptual component and the influence of Jasper Johns were also important in him. At the Primary Structures exhibition, he exhibited L-Beams (1965), large L-shaped plywood structures, all the same but placed in different positions, granting diverse enjoyment; therefore, each element imposed itself on the public as a different work.

Among the minimalists, Sol LeWitt was the artist who privileged the idea over materialism. Indeed, his contribution in the theorization ofConceptual Art is well known. LeWitt’s work simultaneously navigates between the Minimalist and Conceptual spheres, as the author was able to express himself through both mental and concrete visual structures. While recognizing the importance of the moment of making, LeWitt found in the conceptual act a superior creative moment. In 1966 he made Three Squares, elements placed perfectly at a distance from the lines of the edge between walls and floor. The result achieved was the cancellation of three-dimensionality in favor of an expanding effect. With his work, LeWitt exalted the conceptual element by working concretely on the spatial datum, on the action that occurred that modifies space.

In minimalist painting we find Frank Stella. The American painter took on the task of elaborating a radical painting opposed to Abstract Expressionism. He sought to reset the meaning of the act of painting to zero, to nullify all relational instincts and preciosity of painting, asserting the tautological value of the art object: “What you see is what you see,” he said speaking in reference to his black-striped paintings, produced between 1959 and 1960. The modular and repetitive configuration is intended to reinforce the physicality of the object-painting.

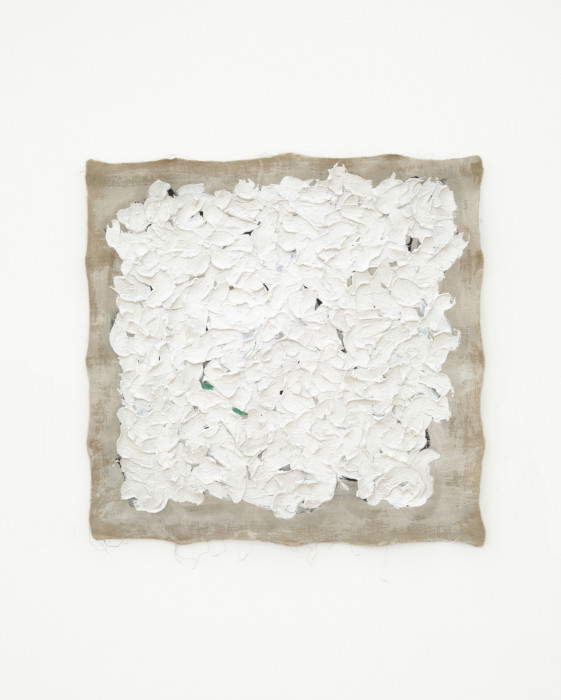

The painter Robert Ryman (Nashville, 1930 - New York, 2019), took the process of minimal reduction of art making to the extreme. He proposed the canvas as a concrete support and painting in its incisive physicality. However, unlike Frank Stella, he did not use geometric configurations, but focused on the material essence of painting, giving infinite importance on the process of painting, on the laying down of the paint material. In Untitled, 1962: full-bodied white brushstrokes dart across the surface, which by the nature of the color go canceling each other out, becoming minimally recognizable in the curves of the brushstrokes, which take on a small relief. For Ryman, the painter’s actions must be mentally enhanced and expressiveness, physical involvement minimized, an idea of reduction and concentration.

|

| Minimalism, history and artists of the reductionist movement |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.