Medardo Rosso (Turin, 1858 - Milan, 1928) was a sculptor who was among the leading proponents of modern sculpture. He came into contact with the Impressionists and in turn was greatly admired by the Futurists, thus placing himself among the various avant-gardes that came to life between the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. He made different versions of the same subject by manipulating materials of various kinds. He became famous for his “unfinished” sculptures in which he captured perceptions in lieu of actual images.

Merdardo Rosso’s sculpture was born in the naturalist sphere but underwent radical transformations after the Turin-based artist became acquainted with the work of Auguste Rodin and the Impressionists in Paris in 1889, so much so that he is considered one of the leading sculptors close to Impressionism: with his sculptures, in fact, Medardo Rosso, by continuously exploring the potential of all materials, especially those that are easier to model (wax and plaster), managed to create works that give the sense of the impression of a moment to the observer.

Medardo Rosso was born in Turin on June 21, 1858, but about ten years later, in 1870, his family moved to Milan because of a promotion of his father, who was an official of the Piedmontese railways. In 1879 Rosso enlisted as a corporal and was sent to Pavia. There he came into contact with the local school of painting, thus beginning to take his first steps in art and to sell his works, even renting a studio on his return to Milan. He exhibited one of his works at the singular “Indisposizione delle belle arti,” an event organized in 1881 in Milan by the Famiglia Artistica (an association of artists linked to the Scapigliatura movement), so titled in a goliardic manner to contrast with the contemporary Universal Exhibition. Already this episode anticipated a certain intolerance of Rosso to academic teachings, which would be confirmed by his brief one-year experience at theBrera Academy of Fine Arts in 1882, from which he was expelled for his irreverent temperament.

Thanks to his time at the academy, Rosso exhibited two terracotta sculptures in the annual exhibition organized by the institute, and then also took them both to the Esposizione di belle arti in Rome the following year. Following these exhibitions, he gained his first public acclaim. In 1885 he married Giuditta Pozzi and they had their only child, Francesco, in the same year. The marriage, however, lasted only four years. After the marriage ended in 1889, Rosso moved to Paris, having participated a few months earlier in the Universal Exhibition with five bronzes that attracted critical attention. The first years in Paris were not easy because of financial straits, but soon Medardo Rosso began to receive several requests from private collectors, most notably Henri Rouart.The latter was an industrialist and art collector, who came to the sculptor’s great assistance, as he purchased several of his works, commissioned a monumental portrait, and put part of his factory at the artist’s disposal. Most importantly, Rouart was passionate about the works of the Impressionists, and he put Medardo Rosso in touch with Edgar Degas. Over the years, Rosso exhibited his sculptures in several European cities, including Paris, Venice, London, and Vienna, often participating in universal exhibitions.

During his first solo exhibition in Paris in 1893, the sculptor met Auguste Rodin, with whom he initially established a friendly relationship. However, relations deteriorated over time due to heated debates between the two about Impressionist sculpture, until an irreparable clash occurred when Rodin denied any influence Rosso may have had on his sculpture. This clash would seem to have been at the root of the marginalization Rosso suffered, and he turns out to be absent from Parisian exhibitions in later years. At that point, the sculptor began to head for Germany and the Netherlands, mainly through his relationship, sentimental and professional, with Etha Fles, a writer, artist, and art critic. It was she who arranged for Rosso to be featured in a traveling exhibition of the Impressionists in the Netherlands of all places.

Recognition in France, however, did not take long to reconsolidate, to the point that the artist was granted French citizenship in 1902, and in 1907 the French prime minister at the time, Georges Clemenceau, wanted two of his works (the plaster of Ecce puer and the wax of Femme à la voilette) to be included in the Musée du Luxembourg, dedicated to artists still living. In the years that followed, Rosso resumed exhibiting in French exhibitions. Gradually, the sculptor began to be noticed more and more widely in Italy, from which he had been missing for a very long time, and gradually began to reconnect with it. In particular, the futurist Ardengo Soffici spoke about him extensively in the periodical La voce. In 1910 Rosso appeared in the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters as an emblem of modern sculpture, a statement reiterated again the following year in the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture where he is pointed out as the source of origin of modern sculpture, recognizing his ability to go beyond the typical patterns of technique by succeeding in representing the atmosphere along with the subject.

In 1914 he participated in the Venice Biennale meeting with great success. On this occasion he met the director of Ca’ Pesaro, Nino Barbantini, who purchased some works for the Ca’ Pesaro museum and received others as gifts from Etha Fles. The sculptor planned to return to Italy in those years, but had to postpone it until 1922 because of the outbreak of World War I. So he began to move between France, Italy and Switzerland, where his companion had meanwhile moved, while still continuing to have relations with the Italian Futurists.In the postwar period, the figure of Margherita Sarfatti was fundamental for Rosso, as it was she who suggested in 1923 that he be appointed high national adviser for the plastic arts, as well as dedicating a room to him in the Novecento Italiano (the movement to which Sarfatti had given birth) exhibition at the Permanente in Milan in 1926. Medardo Rosso died shortly thereafter, on March 31, 1928, from complications of a leg wound, having, moreover, been ill with diabetes for some time. He was cared for by his son Francesco, with whom he was reconciled after a period of estrangement. His remains are preserved in Milan’s Monumental Cemetery below a bronze reproduction of the work Ecce puer. After his death, his son found himself with a considerable number of works scattered among various studios in Paris and Milan, so he decided to bring them together in a museum named after his father’s memory. A 17th-century church in Barzio (Lecco), a resort town where Rosso and his wife often went during their son’s childhood, was chosen as the site.

Medardo Rosso turns out to be innovative for his time, as he managed to bring into plastic matter echoes of the Scapigliatura, the artistic and literary movement born in Milan in the second half of the 19th century, later opening up to Impressionism. In open and decisive contrast to the culture defined as traditional, which deliberately avoided presenting themes deemed unseemly or scabrous (such as physical and mental illness, erotic pleasure and the like), the Scapigliati artists, especially in the early stages, favored works whose details were elusive and barely hinted at. Medardo Rosso fit into this ferment by making sculptures that seem to keep expanding in space. The sculptor worked with a variety of materials, often inserted all together in a single mixture, from wax to bronze to terracotta to plaster to pencil colors. To lend realism to his works, he sometimes inserted some real objects into them, as he did in some early sculptures: he added a pipe to El locch (1882) and a lantern in Innamorati sotto il lampione (1883).

During the 1880s he executed several busts for the Monumental Cemetery in Milan, which were quite different from the classic monumental-style busts and, on the contrary, were quite dynamic. Also dated around these years is a pendant pair, The Old Man and The Ruffian (both 1883). Especially in the second sculpture, Rosso pushes toward physiognomy. A curiosity related to these two works is that Rosso exhibited them on several occasions both in Italy and abroad, sometimes simply re-presenting it under different names. In fact, he can be found exhibiting it under the names “Philemon and Bauci” (the protagonists of a mythological tale reported by Ovid in the Metamorphoses, an allegory of hospitality and unbreakable bonds) or “Faust and Marguerite” (the characters of Wolfgang Goethe’s Faust ). This tendency to give different names to the same work, or vice versa to use the same name for different works, recurs often in Rosso’s production.

The year 1883 seems to be a decidedly prolific one for Medardo Rosso, who continues to make sculptures that categorically reject the “in the round” technique, including the famous work La portinaia (1883). In the works of the 1990s, Rosso took to depicting whole figures (he usually depicted only details such as the face or half-length torso) and seeking solutions to include both figure and environment in the sculptures. Emblematic in this regard is The Man Reading (1894). During this same period, Rosso bought a new private space where he built furnaces to carry out experiments with metals, melting them down to compose alloys, and to begin working with wax. This was then the material with which he became most famous. Initially he worked with rather light, white and yellow waxes, and then switched to a darker wax, alternating at times with a glossy wax with green highlights. However, he never completely abandoned light tones, which, indeed, ultimately turned out to be the most widely used.

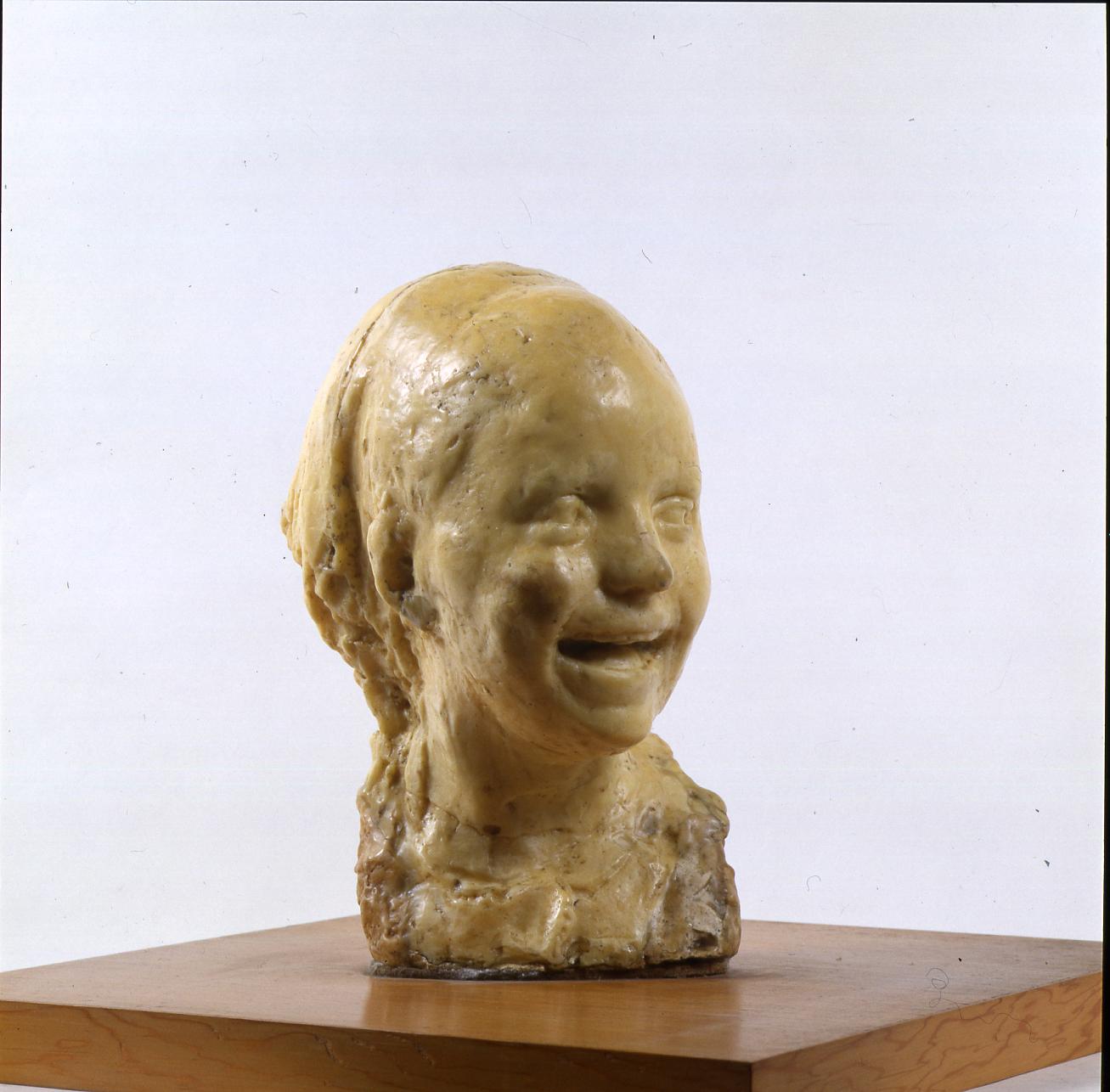

In Medardo Rosso’s last artistic phase there is a recurring subject, namely children, whose purity and innocence he loved. Some works on this theme were conceived during a period Rosso had to spend hospitalized in a Parisian hospital in 1899 due to diabetes. Among the most famous are Child Laughing (1889), Child in the Sun (1890-92) Sick Child (1893-96), L’enfant juif (or Jewish Child) (1892-93).The work that most celebrates boyhood is Ecce Puer (c. 1906), which depicts a child named Alfred Mond but which, on a deeper level, is meant to represent the awe that children feel when confronted with new things that are trivial to adults. Rosso made numerous variations of this sculpture, using different materials as was his custom.

Also in the last years of his life he devoted some sculptures to the theme of laughter as a vital element, proposed in Rieuse (1890), an alternative version of the Laughing Girl of the previous year, and Grand Rieuse (1903) whose features would seem to be attributable to the café-concert singer Bianca da Toledo. In addition to sculpture, Medardo Rosso also devoted himself over the years to photography, considering it an art in its own right by exhibiting some of his photographic works in exhibitions or devoting himself to experiments on the object itself, manipulating it, cutting it out and recomposing it into collages. He also accompanied these works on photography with some written texts, both published and remaining private.

As mentioned earlier, Medardo Rosso produced several versions of the same work, using different materials or making some variation in composition. Therefore, works with the same name turn out to be found in different locations. Almost all of the works are preserved in Italy. In Turin, his birthplace, it is possible to admire the sculptures Aetas aurea (1886) and the later Bimbo al sole (1890-92) at the GAM - Galleria d’Arte Moderna.

In Milan, an important city for his biography, they are preserved: La Ruffiana (1883) in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna (1883) (a copy of the pendant with The Old Man is also kept at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Noderna e Contemporanea in Rome), La Portinaia (1883), Grande Rieuse (1903), a version of L ’ Man Reading (1894) and a plaster version ofEcce puer (1906), while La Petite Rieuse (1889), and L’enfant juif (or Jewish Child) (1892-93) are in the Pinacoteca di Brera.

Other versions of the sculptor’s major works are grouped in the Medardo Rosso Museum in Barzio, which opened in 1928. Finally, a very substantial nucleus of sculptures can be found in Rome, where Il bersagliere (1881-82), Bambina che ride (1889) and Uomo che legge (1894) are at the Palazzo delle Belle Arti, while El Locch (1881-82), Gli Innamorati sotto il lampione (1883), Bambino malato (1893-96) and a wax version ofEcce puer (1906) are at GNAM - Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome.

|

| Medardo Rosso, life works and style of the impressionist sculptor |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.