Maurizio Cattelan: major works, themes of his art

Histrionic, provocative, and an artist capable of making even those unfamiliar withcontemporary art discuss and become the subject of debates that often transcend the boundaries of the field: we are talking about Maurizio Cattelan (Padua, 1960), perhaps the best known and internationally recognized Italian artist today. Cattelan is one of the greatest artists of the last two decades: with his provocative works that run on the edge of reality and fiction, in which parody and tragedy are often mixed with an irony that is anything but subtle (indeed: Cattelan is a master of sarcasm), founded often on paradox, quotation, playfulness, and the ability to raise indignation and irritation with the public, Cattelan has earned a prominent place in the history of art. An artist capable of outraging public opinion even at a time when everyone seems to be asleep from addiction to what television feeds us, Cattelan succeeds in scandalizing, intriguing, causing discussion, and above all, making the recipients of his works think.

But how can he who is perceived by most as a “provocateur” carve out a prominent role in art history? It is quickly said: Cattelan is one of the world’s leading exponents of so-called relational art. As Monet is among the best Impressionists, as Picasso is a Cubist par excellence, as Pino Pascali was one of the masters of arte povera, so Cattelan is one of the masters of relational art: these are practices defined in different ways by critics (who have used expressions such as “social sculpture,” “relational aesthetics,” and “participatory art”), but in terms that indicate a trend that has developed since the 1990s, with artists such as Carsten Höller, Pierre Huyghe, Vanessa Beecroft, Miltos Manetas, Philippe Parreno, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and Cattelan himself, and which sees artists abolishing the boundaries between art, the public, and life. The expression “relational aesthetics” was first employed in 1996 by critic Nicholas Bourriaud, who precisely singled out Cattelan as one of the main exponents of this art: according to the Frenchman,relational art is “an art that takes as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private space.” Relational art, in short, has little to do with the “physical” limits imposed by an exhibition space or the temporal limits imposed by the duration of an exhibition. If anything, the space in which relational art operates is a social context.

And since the relational artist must be able to operate within this kind of context, it becomes clear why Cattelan is also a very skilled communicator, who knows to perfection the workings of the media, as well as the art system that he habitually mocks. And in this, Cattelan is one of the great masters of relational art (if not perhaps the most skilled ever in this respect). One more “shot” after Duchamp and Beuys. The means by which Cattelan creates his works are the most varied: from traditional ones (for example, the sculptures that the artist creates in collaboration with specialized workshops), to those instead more distant from tradition, such as performances, provocative actions, and his own participation in certain events. Always keeping in mind some indispensable factors for the artist’s work: skill, motivation and attitude, as the artist himself explained in an interview he granted to Finestre Sull’Arte.

|

| Maurizio Cattelan |

Maurizio Cattelan: biography

Maurizio Cattelan was born in Padua on September 21, 1960, to a family of modest origins: his father Paolo is a truck driver, his mother Pierina is a cleaning lady. He is the only boy of four children (he has three sisters, Luisella, Giada and Cristina). After dropping out of school and starting to work when he was only 17 years old out of family necessity (although he will manage to graduate from the evening classes later), doing odd jobs such as gardener or electrician, the artist trained as a self-taught artist between Forlì and Bologna in the 1980s, attending the circles of theAcademy of Fine Arts in the Emilia capital although he did not attend classes or enroll in courses. In fact, however, Cattelan does not receive traditional training: rather, he studies and learns by observing. Also in the 1980s, in Forlì, the artist began to work designing and producing wooden furniture. His “artistic” debut came relatively late: the very first work, Untitled, is from 1986 and is a sort of “revisitation” of Fontana’s cuts (with the gashes arranged to form a kind of Z of Zorro), and a photographic work entitled Lessico Familiare (Family Lexicon ), borrowing the title of the well-known novel by Natalia Ginzburg, is from 1989 (it is the first of Cattelan’s countless self-portraits). In contrast, his exhibition debut dates back to 1991. That year, Cattelan managed to crash Arte Fiera, Italy’s longest-running modern and contemporary art fair, exhibiting an “Abusive Stand” in which he sold gadgets of a fictitious soccer team, A.C. Forniture Sud. Also in 1991, the artist exhibited for the first time in a ... non-abusive way, with the Stadium project at the then Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, now MAMbo (the project consisted of an immense foosball table that could be played by eleven players on each side, and he organized a live game at the museum).

In 1993 he was invited to the Venice Biennale, where he already provoked the public with the work Working is a Bad Trade: in practice, Cattelan rented the space reserved for him to an advertising agency. In the 1990s he worked on a number of famous works making use of taxidermy( 1996’sBidibidobidiboo, or the very famous Novecento of 1997), leading up to 1999 with the iconic masterpiece La Nona Ora, the sculpture depicting Pope John Paul II being struck by a meteorite. Also in the same year, for the work A Perfect Day the artist glued his gallery owner Massimo De Carlo (who, moreover, would have to be rescued at the end of the performance) to a wall with gray packing tape. Again, in 1999 he curated a mock “Caribbean Biennial,” even making a catalog and organizing a press conference (while real curating came in 2006, when together with Massimiliano Gioni and Ali Subotnick he curated the Berlin Biennial).

In 2001 Cattelan baffled the art public and beyond by creating the sculpture Him, which depicts Adolf Hitler intent on praying on his knees: the work was auctioned at Christie’s for the sum of more than $17 million. It was still a scandal in 2004, when the Venetian artist hung dummies of some hanging children from a tree in Milan, near Porta Ticinese, and again in Milan, in 2010, he installed the work L.O.V.E., the famous “middle finger” in front of the stock exchange in Piazza Affari, with the finger for facing not toward the stock exchange, but from it toward the square, thus toward the city. In 2010 the artist founded the magazine Toilet Paper, and the following year he participated in the Venice Biennale presenting himself with two thousand stuffed pigeons: in the same year at the Guggenheim in New York there was a major exhibition of 130 of his ceiling-related works. In 2013 he made a mockery of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna, which awarded him the Francesca Alinovi Prize. The artist sends in his place, to collect the prize, the comic duo of I soliti idioti (Fabrizio Biggio and Francesco Mandelli), who give a farcical performance, arousing the indignation of the critic Renato Barilli, who also until shortly before the intervention of the two comedians had incensed Cattelan.

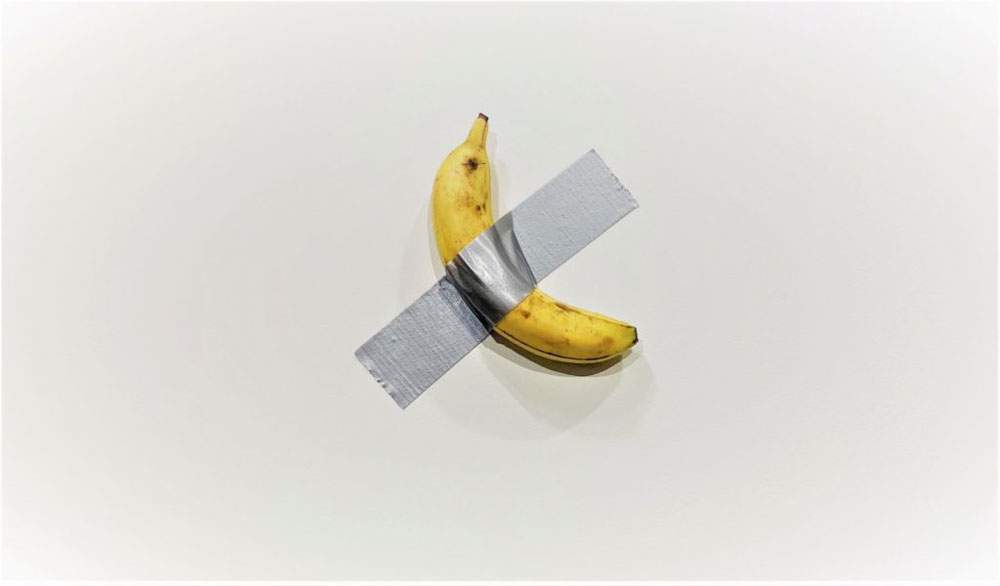

Cattelan’s most recent works include the celebrated America, an 18-karat gold-covered toilet first exhibited at the Guggenheim in New York and stolen in 2019 in England while on display in an exhibition at Blenheim Palace; Eternity, a provocative cemetery with the graves of artists from throughout art history, including Cattelan’s own; and Comedian, the banana hanging on the wall with duct tape that shocked the world in late 2019. Among the awards he has received are an Honorary Degree in Sociology from the University of Trento (2004), the Lifetime Achievement Award from the XV Quadriennale d’Arte in Rome (2008), and the title of honorary professor in sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara (2017).

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, Working is a Bad Trade (1993) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, A perfect day (1999) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, America (2016; 18 karat gold) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, Eternity (2018) |

Maurizio Cattelan’s major works

A reading of Cattelan’s oeuvre through some iconic works can start precisely with Familiar Lexicon from 1989: here, the artist photographs himself shirtless, making the sign of the heart, with his hands, at chest level, and inserting the image inside a silver frame. This is already a provocation based on a kind of détournement: the silver frame, the quintessential symbol of the bourgeois interior (and which Cattelan says he stole from the home of his then girlfriend), accommodates an image that has nothing bourgeois about it and therefore distorts the meaning of the object. It is a kind of allegory of the artist who resents the constraints of the art world represented by that very frame. Moreover, provocation is one of the foundations of Cattelan’s art, as he demonstrated to the world in 1993 with the work Working is an ugly profession, with which, as mentioned in the biography, the artist simply rented the space in which he was to exhibit at the 1993 Biennale. But provocation is never an end in itself. For example, with Novecento, the very famous stuffed horse hanging from the ceiling, now at the Castello di Rivoli, alludes to an existential condition in which the human being is deprived of the ability to act, just like the horse lifted off the ground without the possibility of movement. “An unprecedented version of still life,” the museum itself explains, “the work conveys a sense of frustrated tension, an energy destined to find no outlet.”

The Ninth Hour is the famous work in which Pope John Paul II is felled by a meteorite: the title refers to the ancient scanning of the hours of the day, such that the ninth hour corresponded roughly to 15 today (i.e., the time Jesus died on the cross). The work was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in London: it was immediately discussed for its desecrating charge, with the image of Pope Wojtyla, who enjoyed immense popularity among the faithful, becoming almost a grotesque caricature. And by many it was considered an outrageous and blasphemous work. It is a work that is not easy to read and yet could still allude to an existential condition, that of man who is tormented by evil but who, despite suffering the blow, reacts (the pope in fact is not dead in Cattelan’s depiction) and sticks solidly to his values (in this case represented by the cross). Cattelan’s works in fact make themselves bearers of contemporary content, often telling of the crisis of late 20th century society, and they do so with works that radically renew the language of art. Cattelan’s works, however, are never to be read according to a single key: interpretations can be diverse. Take, for example, Him, the work that depicts Hitler in the act of praying, on his knees: it could be a symbol of the impossibility of forgiving the dictator for the evil he has done (the artist, moreover, exhibited it in 2012 at the Warsaw Ghetto, arousing endless controversy as it was considered a simple provocation). But it could also be an allegory of evil that initially presents itself with an innocuous appearance. The “provocation,” however, certainly succeeds in opening a reflection, a discussion.

This is what the artist managed to do very well with Hanged Children of 2004 (an untitled work), provocative to the point that some Milanese climbed the tree at Porta Ticinese to remove the dummies: perhaps a reflection on the condition of childhood (by the way, note how the children have their eyes open). And perhaps even better with L.O.V.E. , one of his most ambiguous works (ambiguity is another characteristic of Cattelan’s art): is it a sign of protest against the world of finance, or is it the great economic potentates who, by turning the middle finger toward ordinary people, are making fun of them? Another topic often present in Cattelan’s work, from the very beginning(Stadium in 1991, with the teams playing foosball made up of Cesena players on one side and Senegalese immigrants on the other, was a reflection on racism), is that of politics, to which America might allude: the Guggenheim, the museum where it was first shown, exhibited it by linking it to Donald Trump’s career (the aesthetics of the toilet recalls that of Trump’s excessive residences), but the artist rejected this as the only interpretation (in fact, it could also be an interpretation of Duchamp’s famous Fountain, made almost a hundred years earlier, in 2017). And then we come to Comedian: a kind of mockery of the art system. Cattelan, in short, never ceases to amaze and cause discussion.

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, Family Lexicon (1989; black-and-white photograph in silver frame; 18 x 13 cm) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, Novecento (1997; taxidermy horse, leather sling, rope, 200 x 70 x 270 cm; Rivoli, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, The Ninth Hour (1999; polyester, resin, volcanic rock, carpet, glass, metal powder, latex, wax, fabric; Private collection) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, L. O.V.E. - Liberty Hate Revenge Eternity (2010; Carrara marble, height 1100 cm; Milan, Piazza Affari). Ph. Credit Luoghi del Contemporaneo - Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism. |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian (2019; banana and tape) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan: major works, themes of his art |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.