Mario Sironi, life and works of the master of the Italian twentieth century

Mario Sironi (Sassari, 1885 - Milan 1961) was one of the most celebrated artists of the first half of the 20th century. Throughout his career, Sironi joined several artistic currents and even founded one with other artists, as in the case of the Novecento Italiano movement. Over the years, Sironi was a member of Futurism, the Italian avant-garde movement born in 1909 with the famous manifesto of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Alexandria, Egypt, 1876 - Bellagio, 1944). After that for a time he was also influenced by the Metaphysical current, founded in the 1920s by Giorgio de Chirico, andexpressionist painting. In addition, Sironi moved to the forefront of reviving mural painting, of which he became the most important exponent of his time.

However, his brilliant artistic career was tainted by his staunch adherence to the fascist political movement, in which he saw a springboard for the rebirth of Italy and consequently Italian art. Over the years Sironi had close relations with the regime, for which he set up several exhibitions and many pavilions. What is more, the painter worked as an illustrator for Popolo d’Italia, the newspaper founded by Benito Mussolini. Because of his closeness to the regime, Sironi’s works were discredited for most of the second half of the twentieth century. On the other hand, a reappraisal of Sironi’s corpus has been underway in recent years that, without erasing the shame of the painter’s adherence to the fascist movement, is bringing to light the masterpieces of one of Italy’s greatest modern masters.

Life of Mario Sironi

Mario Sironi was born from the marriage of Enrico (Milan, 1847 - Rome, 1898) and Giulia Villa (Florence, 1860 - Bergamo, 1943), both of whom came from two families with artistic traditions. His maternal grandfather, Ignazio Villa, was a sculptor and architect, as was his paternal uncle Eugenio Sironi, while his father Enrico was an engineer and his mother a formidable musician. In 1856, the family moved to Rome, where young Mario pursued technical studies. However, his adolescence was deeply shaken by the untimely death of his father, which occurred when Sironi was only 13 years old. Mario spent his adolescence reading the great French classics, Leopardi, and some of the greatest philosophers. In 1902 Sironi enrolled in the faculty of engineering, which he dropped out of after only a year due to severe depression caused by existential malaise, which marked his entire existence. Thus, under the advice of two artists dear to him, he enrolled in the Free School of the Nude to devote himself to painting. At the same time he came into contact for the first time with Futurist artists, including Umberto Boccioni (Reggio Calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916) and Giacomo Balla (Turin, 1871 - Rome, 1958) and also with the circle of Angelo Prini (Belgirate, 1915 - Pavia, 2008), a future exponent ofArte Povera.

After an initial moment of misunderstanding with Boccioni, due to Sironi’s devotion to the same classical art that Futurism was committed to destroying, the young painter came into the good graces of the Futurist artist. Mario became to all intents and purposes a member of the movement, interpreting its stylistic characteristics according to a volumetric quest, which characterized his style throughout his career. The following years were very fruitful from the point of view of artistic production for the young futurist, who gained his first public recognition from critics. At the same time as this praise, Sironi was invited to exhibit on several occasions, and in 1916 he signed the Futurist manifesto, L’orgoglio italiano (Italian Pride). At the outbreak of World War I, Sironi enlisted in the Volontari Ciclisti battalion, along with his fellow Futurists. The wartime experience lasted until 1918, after which the artist returned to Rome and took part in the Grand National Futurist Exhibition. However, beginning in the 1920s Sironi’s painting was influenced by the suggestions of the Metaphysical current. That same year, Sironi married Matilde Fabbrini, with whom he had two daughters and a very complicated marriage due to the painter’s continuous nomadism. In fact, a few months after the marriage Sironi moved to Milan, where his first urban landscapes were born. In the Lombard capital he became close to Fascism, beginning to attend meetings of the Milanese Fascio.

In 1920 Mario Sironi together with other artists signed the Futurist Manifesto. Against All Returns in Painting, which contained some principles of the future Novecento Italiano art movement. The latter was born two years later from the association between Sironi, Anselmo Bucci (Fossombrone, 1887 - Monza, 1955), Leonardo Dudreville (Venice, 1885 - Ghiffa, 1976), Achille Funi (Ferrara, 1890 - Appiano Gentile, 1972), Gian Emilio Malerba (Milan, 1880 - Milan, 1926), Piero Marussig (Trieste, 1879 - Pavia, 1937) and Ubaldo Oppi (Bologna, 1889 - Vicenza, 1942), supported by art critic Margherita Grassini Sarfatti (Venice, 1880 - Cavallasca, 1961). Novecento promoted a modern classicism, respectful of the national artistic tradition and able to confront modern needs. The group first exhibited at the Pesaro Gallery in March 1923, and following its great success, Sarfatti organized the First Exhibition of the Italian Novecento. The latter was joined by 110 exhibitors, including some of the most important artists of the time: Carlo Carrà (Quargnento, 1881 - Milan, 1966), Giorgio de Chirico, Arturo Martini (Treviso, 1889 - Milan, 1947), Giacomo Balla, Fortunato Depero (Fondo, 1892 - Rovereto, 1960) and many others.

After the great success achieved thanks to the Novecento movement, a very complicated period began for Sironi, both from a work and personal point of view. In fact, in 1930 Mario separated from his wife and the works exhibited at the I Quadriennale in Rome the following year were not appreciated by critics. The failure achieved at the exhibition was due to Sironi’s rapprochement with the Expressionist style, which was not understood by the judges. However, this misleading moment was short-lived, as the artist began to devote himself mainly to public works. These works were characterized by a composite style, reminiscent of the perspective panels of the early fifteenth century. Until 1940 Sironi engaged almost exclusively in monumental painting, putting aside easel painting, deeming it now inadequate for his needs. Moreover, this practice was crowned with the writing of two manifestos: Mural Painting (1932) and the Manifesto of Mural Painting, signed together with other artists (1933). Among the most important works of the period were La Carta del Lavoro for the Ministry of Corporations in Rome (1932) and the two mosaics L’Italia corporativa (1936-1937) and La Giustizia fiancheggiata dalla Legge (1936-1939), both in Milan.

In the following decade Sironi continued his involvement in mural painting, exhibiting a series of tempera paintings under the name Fragments of Mural Works. Meanwhile, Mario remained loyal to the fascist party to the last, even in the most critical final stages. The artist came out devastated by the violence and brutality of the war, during which he even risked being shot. Disillusioned after the Italian defeat, Sironi fell into inconsolable isolation exacerbated by the suicide of his young daughter Rossana in 1948.

Despite the terrible turn of events, Mario Sironi continued to paint, and his painting was tinged with somber and fragmentary tones, as in the case of one of his last pictorial series, Apocalypse.In his final years, the painter continued to exhibit both in Italy and abroad, and in 1956 he was named Accademico di San Luca, a title the artist greeted with ironic bitterness. Mario Sironi died in 1961, following complications from bronchopneumonia.

Mario Sironi’s masterpieces

Mario Sironi’s early works were strongly influenced by ’pointillist art, an artistic current that emerged around the end of the 19th century. The latter recalled the French pointillist movement, in fact it was characterized by the juxtaposition of filaments and lines of color. Divisionist painters’ favorite subjects were motherhood and social themes. Sironi reinterpreted filament painting and the maternal theme in the painting Mother Sewing (1905), in light of the composite and textural style that distinguished him throughout his career.

In the following years Sironi devoted himself to the study of ’classical art, until he fully joined the Futurist movement. Fruit of the influences of the Italian avant-garde were numerous works, including compositions with flamboyant tones and an unmistakable volumetric stylistic signature. However, the young artist came into contact with a new artistic current that characterized part of his production in the 1920s, namely Metaphysics. One of the works in which it is possible to see again the reflections of the current founded by De Chirico is The Lamp (1919). Depicted on the canvas is a mannequin with references to Futurist geometric composition, surrounded by an aura of mystery due to the juxtaposition of male hair with female footwear. As a result, the viewer is confronted with a figure whose gender is difficult to determine, immersed in a dark room and with references to the settings of De Chirico’s metaphysical paintings.

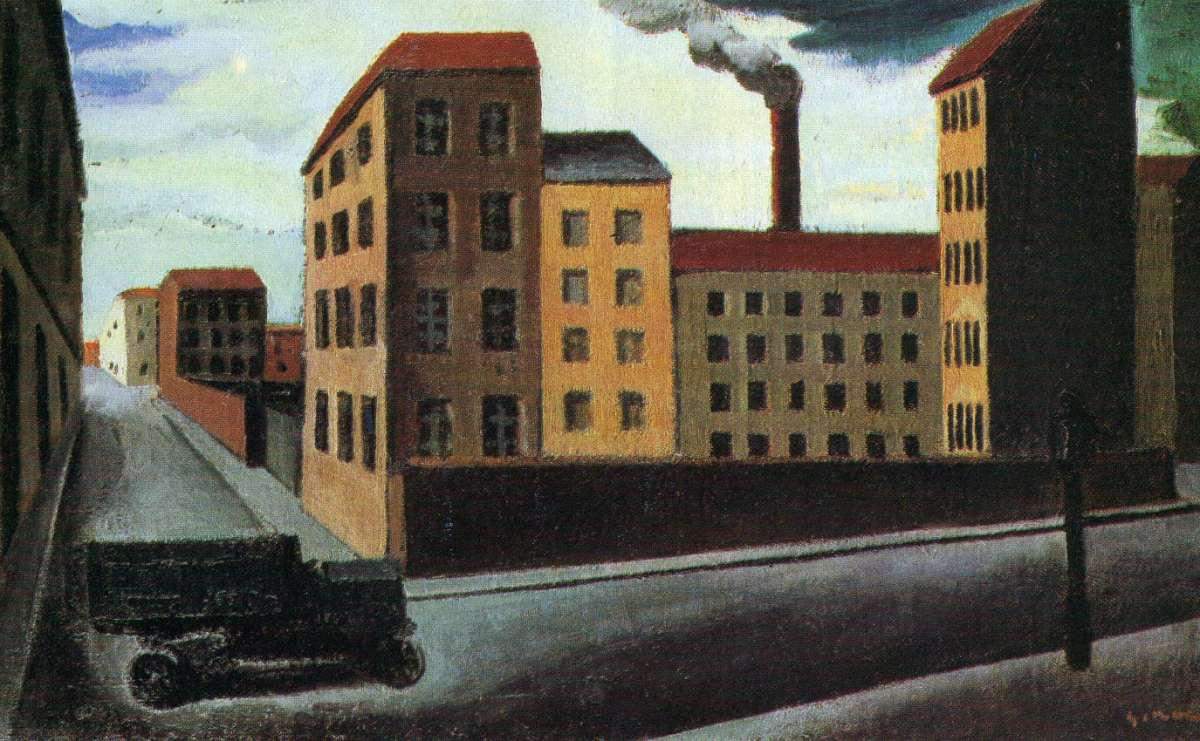

Further developing Mario Sironi’s metaphysical influences and dark inner reflections were the series of Urban Landscapes, his most famous works born after he moved to Milan. Monolithic houses and tall chimneys stand out in Sironi’s city views, scanned according to rigid linear perspectives that give life to bare, gray, lifeless cities. Margherita Sarfatti wrote in her book Storia della pittura moderna: “[Sironi] is the painter of urban landscapes as mechanical and relentless as the geometry of the lives enclosed in the cubes of the houses, between the straight lines of the streets.” So, Sarfatti saw in Sironi’s urban landscapes the same vision of existence enclosed in the mind of the painter, with whom she spent much time together. In fact, for Mario, his lifeless cities mirrored the empty lives of the people living in the suburbs and the distrust in the industrialization of the country.

Sironi reworked this feeling of melancholy and nostalgia for the past numerous times, as in the case of the work: Solitude (1925). This painting depicts a woman looking out onto a balcony within a bare environment, her gaze fixed and mournful beyond the space of the work. The facial features and clothing of the protagonist recall the ’classical imagery, of which the fascist party claimed to be the heir, while the undefined and archaic environment, of metaphysical memory, accentuates the sadness and melancholy of the woman. The latter represents, on the one hand, the drama of contemporary man forced to live in a condition of alienation and subordination to technology; on the other hand, the woman is a symbol of the painter’s distrust of modernity, which was increasingly distancing man from the glorious ancient times.

Beginning in the 1930s Mario Sironi began to devote himself almost exclusively to wall painting. The painter argued for the superiority of mural art over easel art because of its public dimension, which simultaneously removed it from the speculations of the market world. Moreover, according to Sironi, great wall painting would encourage artists to measure themselves with higher themes, going beyond the mere sentimentality of easel paintings. So, public painting met both the needs of the master, who wanted nothing to do with the art market system, and at the same time turned out to be an excellent tool for spreading the ideology of the fascist regime.

One of Mario Sironi’s most famous frescoes is Italy among the Arts and Sciences in the Aula Magna of the University of Rome (1935). The painter planned the design of the work for two years and took three months to realize it, imagining the ’allegory of Italy in the midst of the disciplines of knowledge, divided between the sciences and the arts. Following the fall of the fascist regime, the mural endured atroubled affair, risking destruction because of the fascist symbols on its surface. In fact, the work was subjected to censorship, which resulted in a repainting operation. The latter was aimed not only at removing the fascist elements, but also at permanently changing the figures and colors. After seventy years, it was possible to see the fresco again in its original appearance thanks to a major restoration.

Mario Sironi was one of the most versatile artists of the first half of the Italian twentieth century, and it is important that critics continue to study his artistic journey in order to reconstruct the stages of the birth of modern art in Italy.

Where to see the works of Mario Sironi

Most of Mario Sironi’s works are kept in various Italian museums, for example in Florence, between the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti and the Museo Novecento, in Rome at the Galleria nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, where Solitude itself can be seen, and at the Mart in Rovereto. On the other hand, the largest collection of Sironi’s works of art can be found inside the Museo del Novecento in Milan.

However, as mentioned above numerous works by Sironi are not only kept inside museums, but also in various public buildings. Two canvases made by the artist are preserved in Bergamo: L ’Agricoltura o Il Lavoro in Campagna, and L’Architettura o Il Lavoro in Città (1929-1931). even in Rome there are several mural works by the artist, such as La carta del lavoro (1927-1932) inside the Ministry of Economic Development and the fresco L’Italia tra le arti e le scienze. But once again it is Milan that holds the record, in fact the Lombard capital hosts the largest number of Sironi’s public works. In the city it is possible to see The Fascist Work (1936-1937) at the Palazzo dell’Informazione, the mosaic La Giustizia fiancheggiata dalla Legge (Justice flanked by the Law, bearing the written plates) and a youthful figure, a symbol of strength, bearing the Fascio con la Verità (1936-1938) and the stained-glass window L’annunciazione (1938-1939) at the Church of the Ospedale Maggiore di Niguarda.

|

| Mario Sironi, life and works of the master of the Italian twentieth century |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.