Marcel Duchamp, the inventor of conceptual art. Life, works, style

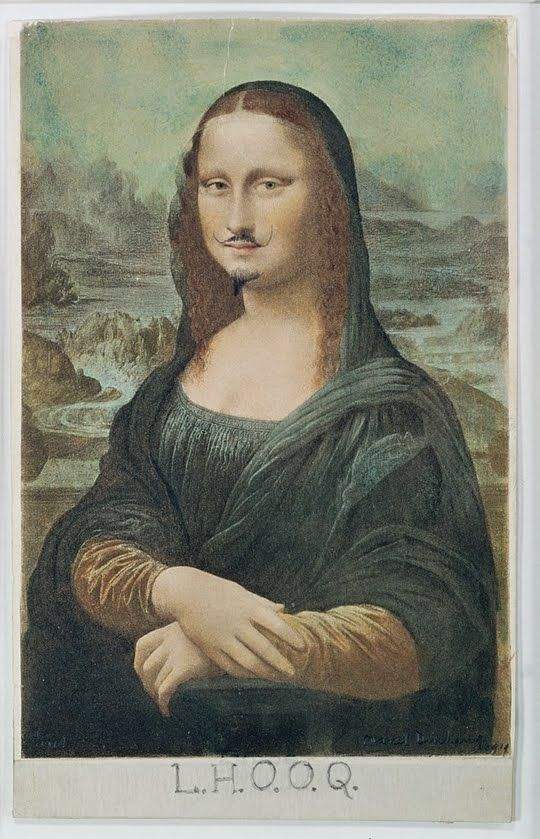

Marcel Duchamp (Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp; Blainville-Crevon, 1887 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1968), a French painter, sculptor and chess player naturalized from the United States, is considered one of the most influential and important artists of the 20th century. Thanks to him, in fact,conceptual art was born, which originated from the intuition of the so-called ready-made, that is, everyday objects that are decontextualized so as to become works of art, carefully selected by the artist himself. Sometimes, however, ready-mades consisted of interventions to alter great masterpieces of the past, as in the case of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa .

Fountain and Bicycle Wheel are Duchamp’s two best-known ready-mades, which are still recognized today as works capable of subverting the artistic conventions of the time. However, the ready-mades were not the only innovation the French artist brought to the art of his time. Duchamp, in fact, had his own idea of art well in mind, rejecting all works that reproduced reality, for example those of the Impressionists, and preferring instead a more intellectual approach, to be deciphered, undoing all the avant-garde currents that had developed in the previous hundred years.

The Life of Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp was born in Blainville-Crevon, France, on July 28, 1887, from the union of Eugène Duchamp and Lucie Nicolle (the latter was the daughter of the painter and engraver Émile Frédéric Nicolle). The parents had had seven children in all, one of whom died when he was very young. In addition to him, three of his siblings were also successful artists, namely painter and engraver Jacques Villon (born Émile Méry Frédéric Gaston Duchamp), sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon (born Pierre-Maurice-Raymond Duchamp), and painter Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti.

Duchamp spent considerable time in America, especially in New York. There, he came into contact with an artist who proved to be fundamental to his life and artistic path, namely the photographer and painter Man Ray. The two met in 1915 and remained lifelong friends. Along with French-Spanish painter Francis Picabia and American photographer Alfred Stieglitz, Duchamp and Ray used to meet in Stieglitz’s gallery 291, professing adherence to a spirit similar to that of Dadaism. Dada was an artistic movement, especially in the visual arts, that arose in response to the traumatic events of World War I by promoting art that was deliberately nonsensical and did not adhere to aesthetic and ideological canons and conventions. The very name of the movement had no meaning. The Dadaist movement is often juxtaposed with Duchamp’s name, although his association with Dada lasted only a few years and occurred particularly in the period of the artist’s youth and beginnings, so he did not have the opportunity to officially adhere to it, but he did embrace some of the basic concepts of the Dadaists.

In 1916, Duchamp founded the Society of Independent Artists, together with patrons Katherine Dreier and Walter Arensberg. He then left the society in protest when they decided not to exhibit the work Fontana (1917), as it was not considered a work of art.

A peculiar aspect of Duchamp’s personality was the creation of pseudonyms and alter egos under which he signed various works. A total of three are known, the first of which was a female character for whom he chose the name Rrose Sélavy. He deliberately sought a Hebrew name, to differentiate himself from the Catholic religion, but he could not find a male name that convinced him, so he decided to opt for a female name and play the role of a woman. The name is a pun that is phonetically reminiscent of the phrase “eros, c’est la vie,” and the double r at the beginning is intentional to create a pun with “arroser la vie.” After all, puns were much loved by Duchamp and he used them very often. Another very famous alter ego of Duchamp’s was R. Mutt, an alteration of the name “Mott,” from the company that produced the urinals that the artist used for some famous works. It was also a reference to a comic strip popular at the time, “Mutt and Jeff.” The letter R. stood for Richard, which contains the English word “Rich” meaning “rich,” thus trying to ward off poverty. Duchamp also invented a joke for journalists, to whom he declared that the pseudonym concealed a friend of his in men’s clothing, even spreading his phone number by passing it off as Mutt’s. A final known pseudonym was that of Marchand du sel, which grew out of Duchamp’s conversations with art historian Michel Sanouillet.

The artist lived in Paris for a long time, except for the period between 1918 and 1923 when he moved to Buenos Aires.

From 1923 onward, Duchamp increasingly slowed down his artistic activity, devoting himself for ten years almost entirely to the game of chess. He reached very high levels in the discipline, even going so far as to be captain of the French team that participated in the Chess Olympiad (he participated in all editions from 1928 to 1933, with his best result being eighth place in 1933). In 1942 the artist was in New York, where he decided to move permanently. In 1954 he married Alexina “Teeny” Sattler Matisse, who remained at his side until the end. He died on October 2, 1968 in Neuilly-sur-Seine and was buried in Rouen Cemetery. An epitaph, composed by himself, can be read on his grave: “D’ailleurs c’est toujours les autres qui meurent” (“On the other hand, it is always the others who die”).

Marcel

Marcel

The style and works of Michel Duchamp

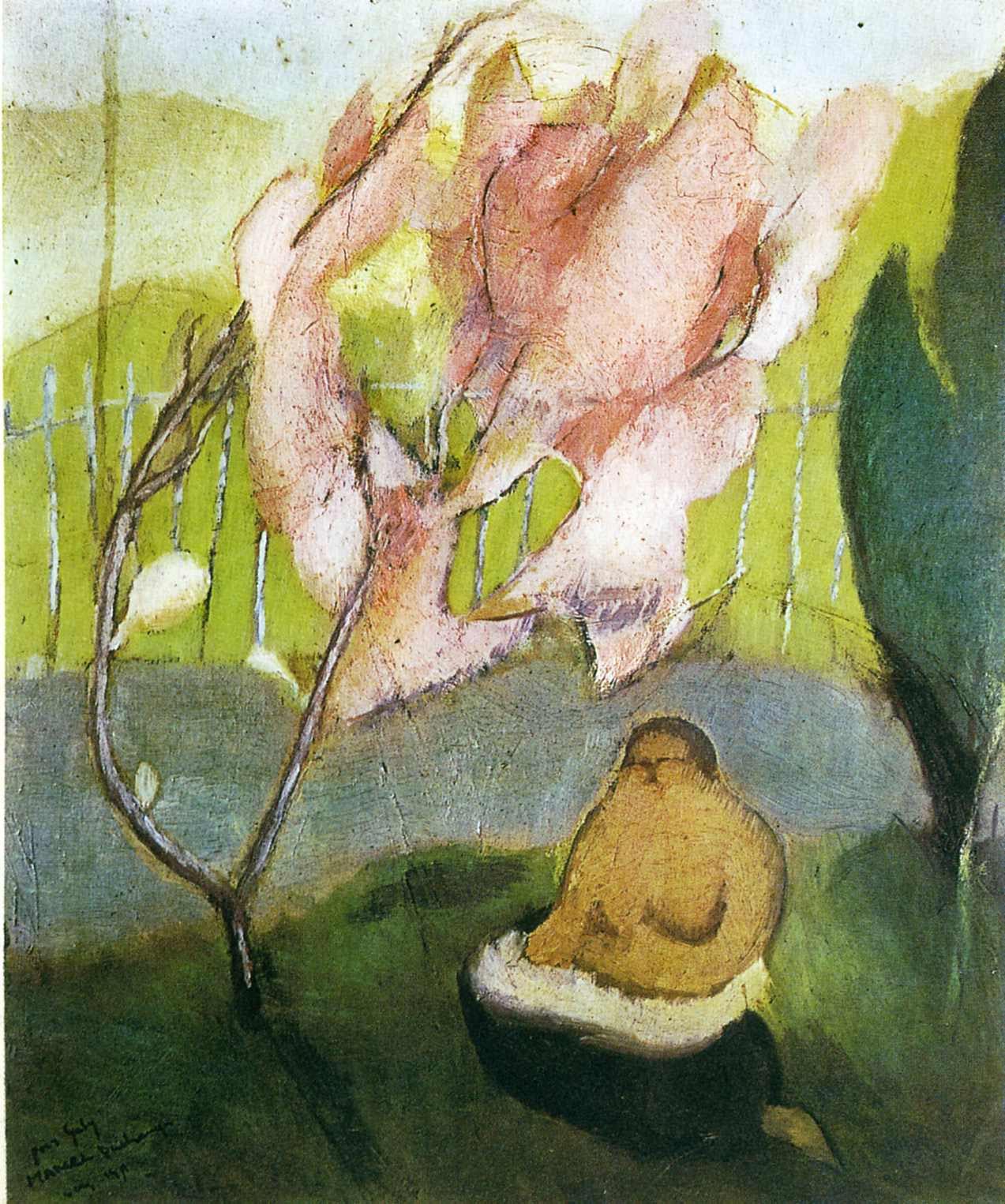

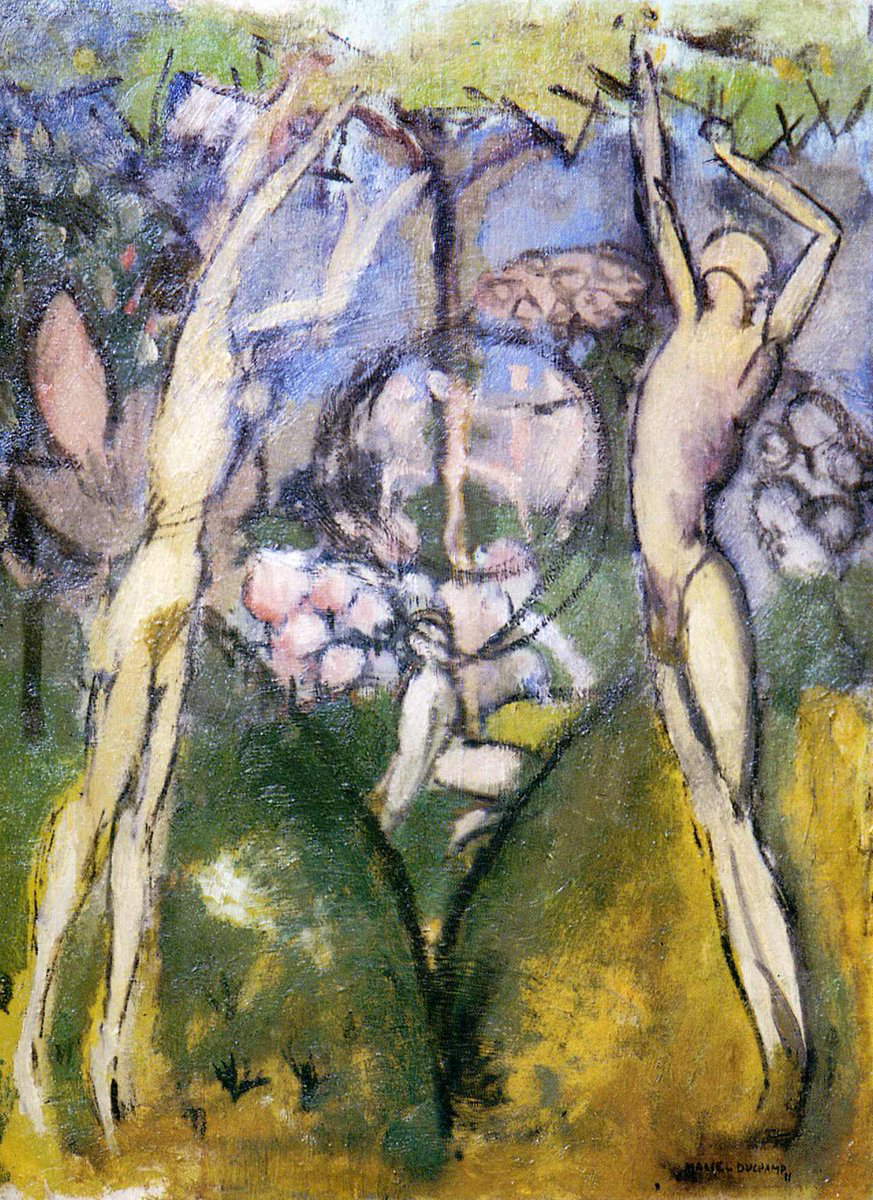

Duchamp’s early works are mainly pictorial, made by 1912, and a total of about fifty are known. At the time, Duchamp was 25 years old. The inspiration for these works came from Impressionism and the Fauves group, as evidenced by the works Air Current on the Apple Tree of Japan, Young Man and Maiden in Spring, and Coffee Grinder, all dated to 1911. The level of these early works was very high.

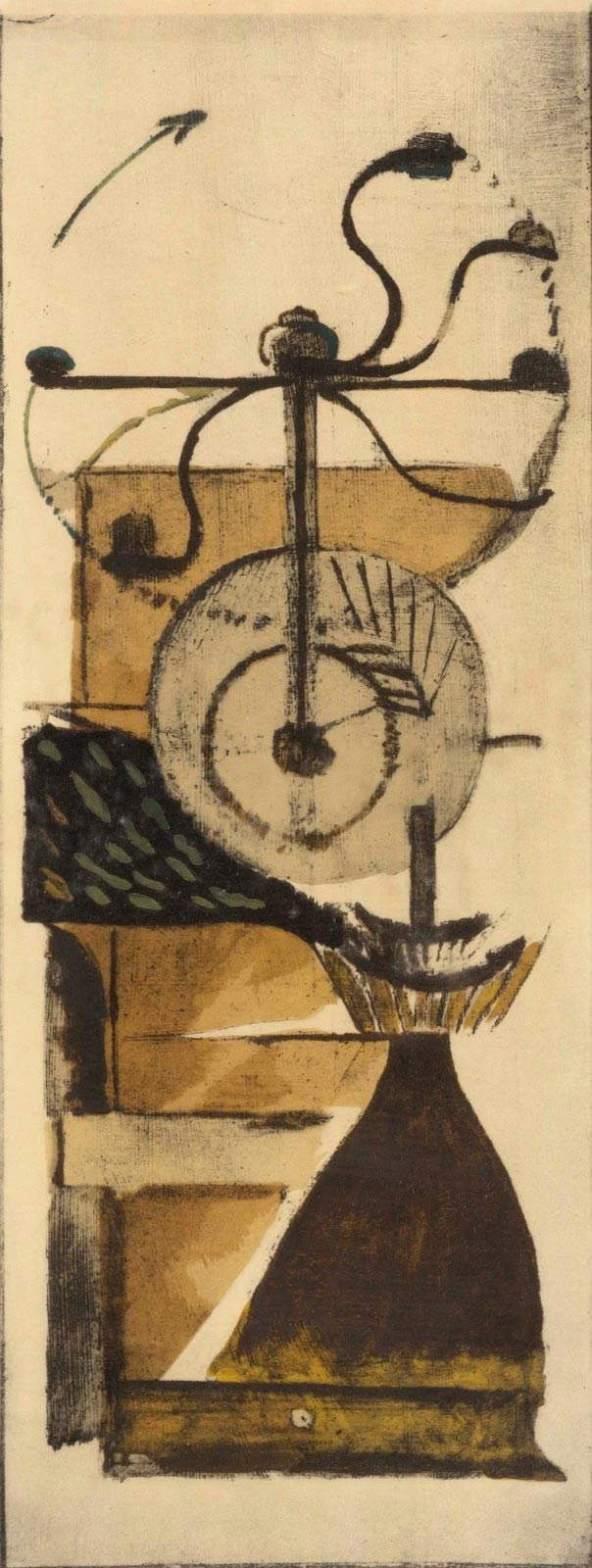

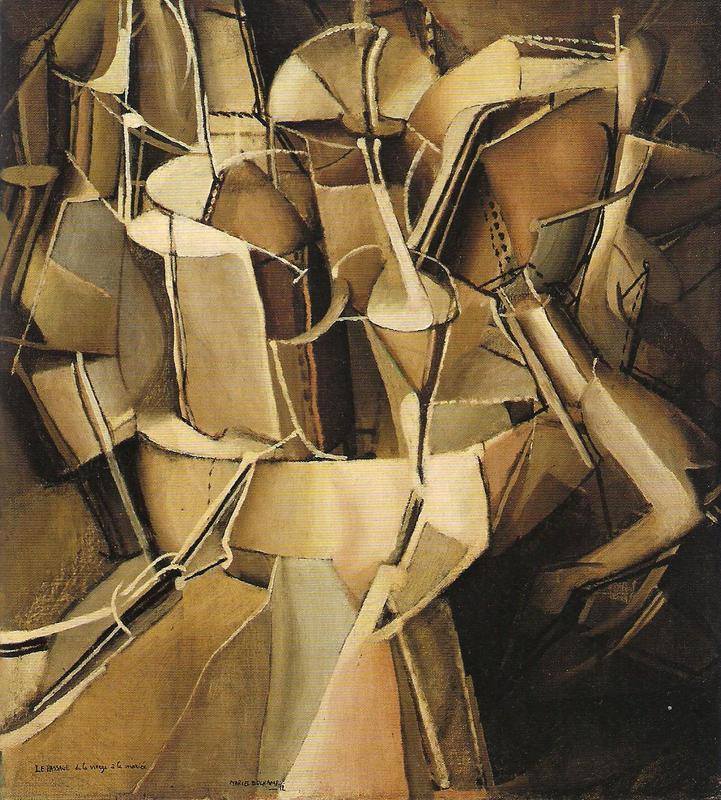

In 1912, however, he began to paint works of a different mold that featured in-depth studies of dynamism, namely Nude Descending the Stairs No. 2, The Transition from Virgin to Bride, Bride. There would seem to be an influence of Futurism in these works, however Duchamp’s contacts with the movement were almost nil, so the basis of his research is to be found in the pioneers of chronophotography Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge. Unlike the Futurists, moreover, Duchamp was not interested in reproducing the same moment taken from multiple points of view, but sought the rendering of movement as moments in succession, depicted one after another until they became infinite. These works were rejected at the Salon des Indépendants, as there was a widespread misconception that they were a mockery of Cubism. The other pictorial works of the period are variations on the same theme, such as The Chocolate Grinder (1913), or drawings and studies for The Great Glass, the work that later marked the turning point in Duchamp’s art.

Duchamp was an artist who always dialogued a great deal with art critics, providing clues and suggestions for deciphering his works. He also gave numerous interviews, in which he expounded personal theories and beliefs about art and painting. Among the most famous statements was the one about painting made in previous years and centuries, which he rejected as “retinal.” By “retinal painting,” he meant all those paintings that privileged aesthetics over content, especially by exalting the most primal instincts. These are his words in support of the concept: “I was interested in ideas, not just visual products. I wanted to bring painting back into the service of the mind [...] In fact until a hundred years ago all painting had been literary or religious: it had all been in the service of the mind. During the last century this characteristic had been lost little by little. [...] Painting should not be merely retinal or visual; it should have to do with the gray matter of our understanding [...] The last hundred years have been retinal. Even the Cubists have been retinal.”

This is the ideological context in which Duchamp lands his most famous and great innovation, the ready-made. Thus following his own conviction that art and painting should privilege a conceptual point of view, Duchamp had the intuition to choose everyday objects, take them out of their context and present them as works of art. The artist’s added value lay in skimming through different objects to find the one that was most suitable to be presented as a work of ’art. The first known ready-made was Bicycle Wheel (1913), which moreover was a symbol of continuity with the search for movement that he had presented shortly before in his paintings. Duchamp produced several ready-mades, including the well-known Fontana (1917), the urinal signed under the pseudonym R. Mutt. The work was never exhibited, due to reluctance to consider it an art object, yet it was reevaluated in the 1950s and had renewed success, to the point that Duchamp made copies to send to various museums. Also in the same years he devoted himself to another type of ready-made, which consisted of retouching famous works. Very famous was his reinterpretation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa , made on a photographic reproduction of the painting to which he applied a mustache on the upper lip and to which he gave the title L.H.O.O.Q . (1919). This work has been interpreted as a manifesto against conformity, specifically targeting one of the universally known artistic masterpieces. The intent was not to denigrate the painting or the artist, but to highlight the hypocrisy of those who appreciate art only when it is pointed out by others as beautiful or worthy.

In the meantime, Duchamp had begun work on another work that would prove pivotal to his output, The Large Glass, which he called "the most important single work I have ever done." He began working on it from 1915, initially giving it the title The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, also. The work consists of two large glass plates, which had dust grains, lead wires and painted metal foils inside them. The upper plate has been interpreted as “the bride,” represented by a small, extremely slender element and accompanied by a cloud probably representing her thoughts. The lower slab, on the other hand, consists of “the bachelors,” minute black figures, resembling the typically male black robes, circling a carousel. There are nine figures in all, and they represent different identities of the bachelor (Cuirassier, Gendarme, Lackey, Bellboy, Vigilante, Priest, Funeral director, Stationmaster, Policeman). They are also known as the “graveyard of liveries and uniforms.” Finally, there is a mechanism that has been interpreted as a water mill, consisting of scissors, sieves, a machine grinding something, probably chocolate, clearly symbolizing desire.

In 1923 Duchamp deliberately left the work "definitively unfinished," leaving for posterity one of the most debated and most fascinating works of contemporary art. The work suffered, incidentally, some damage during a transport, but Duchamp did not want to repair it, stating that it was a way of accepting the identity of the artwork as an inert thing. Duchamp never wanted to call this work a “painting,” but instead called it a “farm machine” and declared, also, that it was “funny physics.”

Duchamp’s last known work is entitled Étant donnés (1969) - Being given: 1. Waterfall of Water, 2. Gas Lighting a large environmental installation consisting of a wooden door with two peepholes that are only noticeable as one approaches the work, through which one can see a scene in which a nude female figure, made of leather, holding a lit oil lamp, stands out against a natural landscape. The title came from some notes related to The Great Glass and is its counterpart, in that while in The Great Glass reality was not present at all, here it is fully present, a factor peculiar to Duchamp’s well-known rejection of “retinal,” realistic art. This choice was justified as a way to find a point of union between the inner world of man and the world outside him.

Duchamp worked on this challenging work for over twenty years, giving everyone the false illusion that he had left art to devote himself to chess. Only his wife was aware of his project. The artist drew up an instruction manual so that it could be reconstructed inside the Philadelphia Museum, where it is still preserved today. Finally, there are the works signed under the pseduonym of Rrose Selavy, namely Belle Haleine - Eau de Voilette (1920), a perfume bottle, Fresh Widow (1920) and Pourquoi ne pas éternuer? (Why don’t you sneeze?) from 1921.

![Marcel Duchamp, Ruota di bicicletta (1913 [1951]; ruota di metallo montata su sgabello di legno dipinto, 51 x 25 x 16 cm; New York, MoMA) Marcel Duchamp, Ruota di bicicletta (1913 [1951]; ruota di metallo montata su sgabello di legno dipinto, 51 x 25 x 16 cm; New York, MoMA)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2022/fn/marcel-duchamp-ruota-di-bicicletta.jpg)

![Marcel Duchamp, Fontana (1917 [1964]; terracotta bianca ricoperta di smalto e vernice, 63 x 48 x 35 cm; Parigi, Centre Pompidou) Marcel Duchamp, Fontana (1917 [1964]; terracotta bianca ricoperta di smalto e vernice, 63 x 48 x 35 cm; Parigi, Centre Pompidou)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2022/fn/duchamp-fontain-pompidou.jpg)

Where to see the works of Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp’s works can be found in museums in Europe and the United States, where the artist himself lived for various periods. In Paris, specifically at the Centre Pompidou, a famous exhibition venue for avant-garde art, one of the most famous ready-mades, Fontana (1917), is preserved. Several well-known works by Duchamp can be found at the Museum of Art in Philadelphia, United States. They are Nude Descending the Stairs No. 2 (1912), The Large Glass (1915-1923) and Étant donnés (1969).

Also in the United States, you can see Bicycle Wheel (1913) and Fresh Widow (1920) at MOMA - Museum of Modern Art in New York. It should also be noted that L.H.O.O.Q . (1919) is part of an American private collection, and Pourquoi ne pas éternuer? (1921) is housed in the Israel Museum.

In Italy, there are two works by Duchamp at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice (they are a Nude from 1911-1912 and a Box in a Suitcase from 1941), while a Young Man and Maiden in Spring (1911) is kept at the Arturo Schwarz Collection in Milan. Precisely several works from this collection, along with the other famous masterpieces, were presented in a major exhibition held in Rome at the GNAM - Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in 2013 to celebrate the centenary of the first ready-made ever made.

|

| Marcel Duchamp, the inventor of conceptual art. Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.