Marc Chagall, life and works of the great Russian-French painter

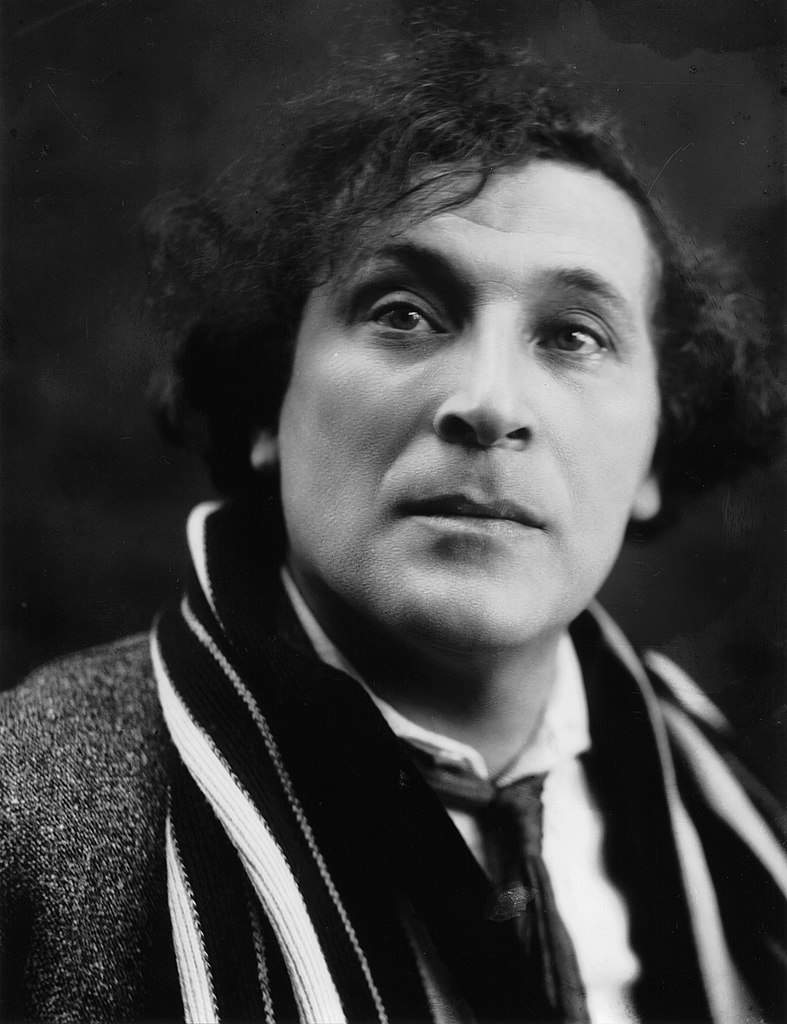

Marc Chagall (born Moishe Segal in Hebrew and Mark ZacharoviÄ Šagal in Russian; Lëzna, 1887 - Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1985), was a Russian painter naturalized French, among the best known of the 20th century. Forced to leave his homeland, he always remained very attached to it, despite the fact that, because of his Jewish religion and his refusal to submit to the dictates of the Soviet regime, he was aware that he could not settle there.

Chagall became famous for his paintings depicting dreamlike and imaginative scenery, with vivid colorful hues and simple lines, imbued with a feeling of joy and serenity. His works cannot, however, be pigeonholed into a particular movement or current; rather, they are expressions of a personal style that draws in part from the contemporary avant-garde and then goes beyond it.

The Life of Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall was born on July 7, 1887, in Lyzna, Russia; however, he spent most of his life in France, acquiring its citizenship. The forced distance from his homeland was experienced by the artist in a tormented way, as he was always deeply attached to his homeland, although he was aware that he could not live there permanently because of incompatibilities due to his religious beliefs, his refusal to adhere to the regime, and his art not approved by the regime. In fact, his family was Jewish and lived near the small town of Vitebsk, which is now in Belarus. On the very day of the artist’s birth, the town came under attack by Cossacks, from which fortunately his family managed to pull themselves out safely. The episode was recounted several times by Chagall, who was so affected by it that he often claimed he was “stillborn.” He was the eldest of nine children, born of the union between his father Khatskl (Zakhar) Šagal, a herring merchant, and his mother, named Feige-Ite. He managed to convince his family to let him pursue a career in art, despite the fact that this profession was forbidden by the Torah, the Jewish sacred text, and began working at a very young age as a retoucher in the workshop of two photographers. Soon after, he managed to gain access to the workshop of the only painter in his town, Yehuda (Yudl) Pen. He often found himself at odds with his master, so after a few months he left the workshop and moved to St. Petersburg, where he enrolled in the Russian Academy of Fine Arts. There, he came into contact with numerous artists and styles, broadening his artistic vision.

Between 1908 and 1910, he studied at a private school with painter Léon Bakst, who introduced him to Western art, particularly the works of Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin, and gave him the suggestion to move to Paris. After all, life in St. Petersburg for Chagall was rather complicated, as the Jewish population could only reside in the city with special permission, and had to be limited to living in their ghetto with specific return times. Chagall was even arrested for contravening the curfew. So in 1910 he decided to go to Paris, where he soon came into contact with the artists who gravitated to the historic Montparnasse district, particularly Guillaume Apollinaire, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, and Eugeniusz Zak.

He returned to Russia again in 1914, making a stopover in Berlin, where he organized his first solo exhibition with the support of the art dealer Herwarth Walden and was well received. Once back in Russia, he had to stay there until 1923 due to the outbreak of World War I, which prevented any movement. In the meantime, he married a young woman named Bella Rosenfeld, featured in several of his paintings, and had a daughter.

He was actively involved in the Russian Revolution of 1917 as a clerk in the Ministry of War, and thanks to this position he managed to avoid conscription to the front. This experience allowed him to associate with important Russian poets, such as Vladimir VladimiroviÄ Majakovsky, collaborate as an illustrator for various books and newspapers, and participate in several group exhibitions. In addition, he was appointed Commissar of Art for the Vitebsk region by the then Soviet Minister of Culture. Under this appointment, he founded an art academy and a museum of modern art. However, the Soviet government soon took issue with Chagall’s artistic directives, and he strenuously opposed the order to make his academy akin to Russian Suprematism, a style imposed by the government, arguing often about it with fellow artist Kazimir SeverinoviÄ MaleviÄ. The celebrated artist taught in Chagall’s academy and was precisely an exponent of Suprematism. When in 1920, upon returning from a stay in his hometown, he found his academy transformed into a Suprematist institution, Chagall resigned from the post and moved with his family to Moscow. There he obtained a position teaching art to war orphans.

The new post was not at the same level as the previous one, and shortly afterwards Chagall managed through a contact to leave Russia again in the direction of Paris in 1923. In 1937 he obtained French citizenship, however within a few years he again had to leave Paris because of World War II and the subsequent persecution and deportation of the Jewish people. Chagall hid with his family in Marseille, then fled to Spain and Portugal until he left for the United States in June 1941. There, he met several European artists fleeing Europe and, thanks to gallery owner Pierre Matisse, son of painter Henri Matisse, participated in several group exhibitions. However, Chagall refused to learn English and continued to speak exclusively in French and Yiddish, the language of the Jewish people. In 1944 he became a widower, and the forced separation from his beloved wife troubled him deeply, leading him to stop painting for several months. He managed to recover with the help of his daughter Ida, who, by the way, introduced him to a woman who later became his companion for seven years and by whom he had another son.

When the war ended in 1948, Chagall returned to Paris a third time, then moved to Provence, where he stayed permanently. That same year he received some important awards, such as a major exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and the award of the Grand Prize for Printmaking at the Venice Biennale. In 1973 Chagall was invited by the Soviet government to travel to Russia, and was triumphantly welcomed in Moscow and Leningrad, while in no way wishing to return to his hometown of Vitebsk. Chagall died at the age of 97 in Provence, in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, on March 28, 1985. His remains were interred in the local cemetery.

The style and works of Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall’s works have some unmistakable traits, among all of which are his preference for bright colors reminiscent of the world of childhood, his choice of sharp shapes and lines reminiscent of the experiences of Cubism, and an overall atmosphere characterized by elements of fairy tale and enchantment. The combination of these elements leads to the difficulty, if not impossibility, of placing Chagall in a precise current; rather, he was an artist capable not only of traversing the various avant-gardes, but of surpassing them, always remaining faithful to a style of his own.

Very close to the European avant-gardes he met in Paris, Chagall came into close contact especially with the Cubists, specifically Robert Delaunay, and then with the Fauves group and the School of Paris with Amedeo Modigliani. However, his artistic sensibility led him away from reality, unlike the exponents of the aforementioned movements, to focus on the more spiritual and dreamlike aspects of human experience. Surrealism could not meet his needs either, as the Surrealists’ goal was to represent the unconscious in image, while Chagall intended to lead the viewer into the oneiric by letting him or her be carried away by the deliberately unrealistic atmosphere. At the same time, the artist brought much of personal experience into his works, from elements of Russian folk traditions to the woman he loved deeply. In both serene and darker moments, Chagall always managed to infuse his works with a general feeling of serenity and magic, just as indeed happens in dreams. Indeed, it would seem that Chagall resorted to a world populated by fantastical figures, naturalistic scenery and simple, flowing lines to escape from the negativity of the real world and to seek, even in a melancholy way, the tranquility and innocence of childhood.

Chagall’s earliest works date from a rather difficult personal period, characterized by scarcity of food and means and a tendency to remain often locked in the clutter of his studio.

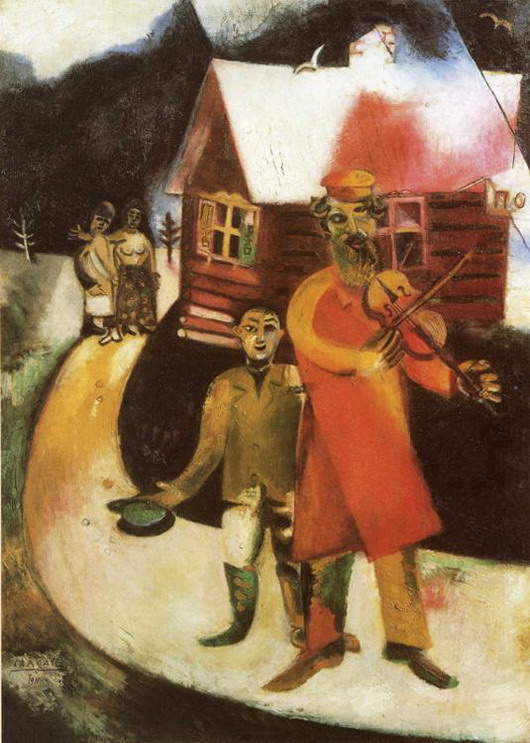

These include The Fiddler (1911), one of the earliest paintings featuring a fiddler, a figure that recurs in Jewish tradition, since dance and song were recognized as the highest form of prayer and communion with God. In this case, the fiddler was represented by Uncle Neuch, and he stands on the “roof of the world.”

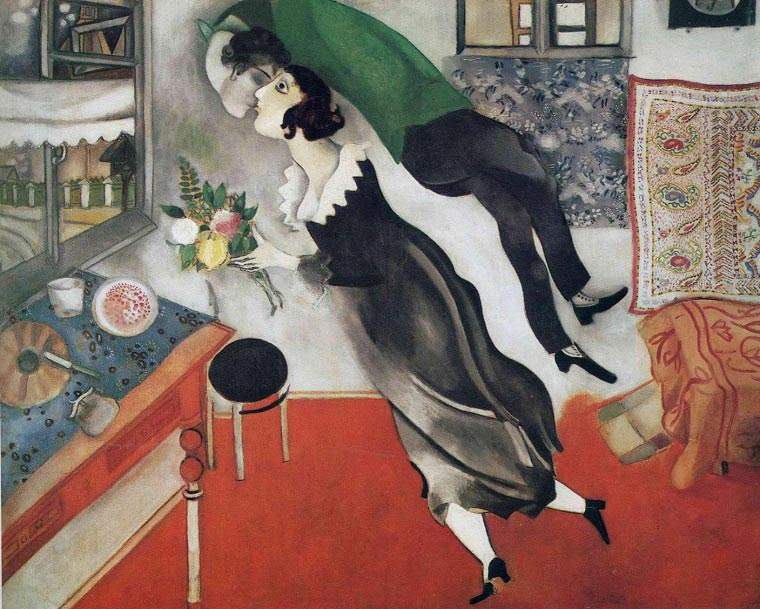

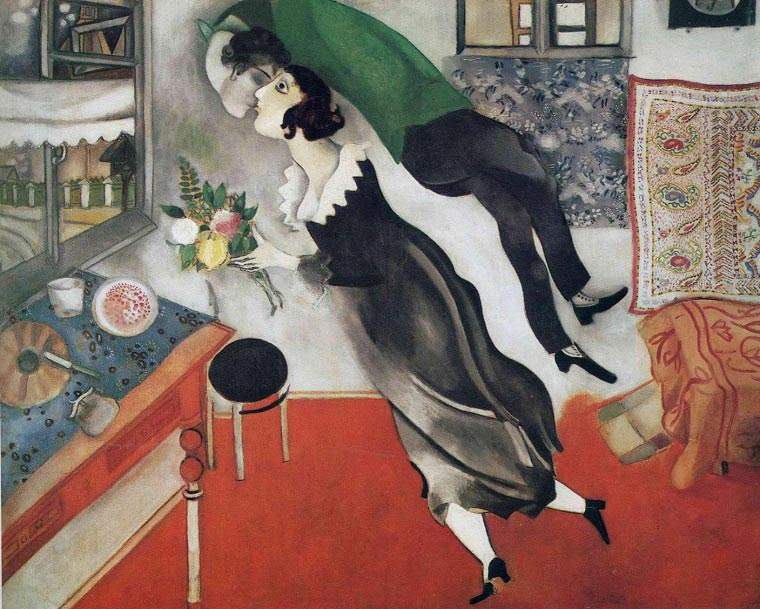

Another very important work of Chagall’s production is Birthday (1915). It is one of the earliest works in which Bella, the artist’s first beloved wife, appears, portrayed at the moment when the artist suddenly decides to kiss her as he was preparing to arrange a bouquet of flowers. The two lovers are portrayed suspended from the floor, as their bodies make decidedly unnatural movements, for example, his legs are depicted undulating, as if moved by the wind in the air, and his neck stretches and twists improbably to kiss his beloved. The tones of the painting are warm, ranging from red to brown to white. The room in which the scene takes place is very well detailed; it is a metaphor for the perfection that becomes possible only in the presence of his wife.

It also celebrates the masterpiece The Walk (1918), in which the protagonists are once again Chagall himself and his wife Bella. During a walk together, hand in hand, he has his feet on the ground, while she hovers in the air, always holding on to her husband’s hand, while in the other hand she holds a small bird, a symbol of their close connection with nature. There are several references to his homeland in this work; in fact, the scene is set in a landscape of the small town of Vitebsk, and a traditional Russian picnic tablecloth is also depicted on the lawn. The meaning of the scene lies in the concept that love is able to overcome any limitation, even natural ones, as in the detail of Bella rising into the air unable to do so normally. In the background, the rooftops of Vitebsk are portrayed, all the same except for the synagogue, which is painted in a different color to highlight its spiritual function.

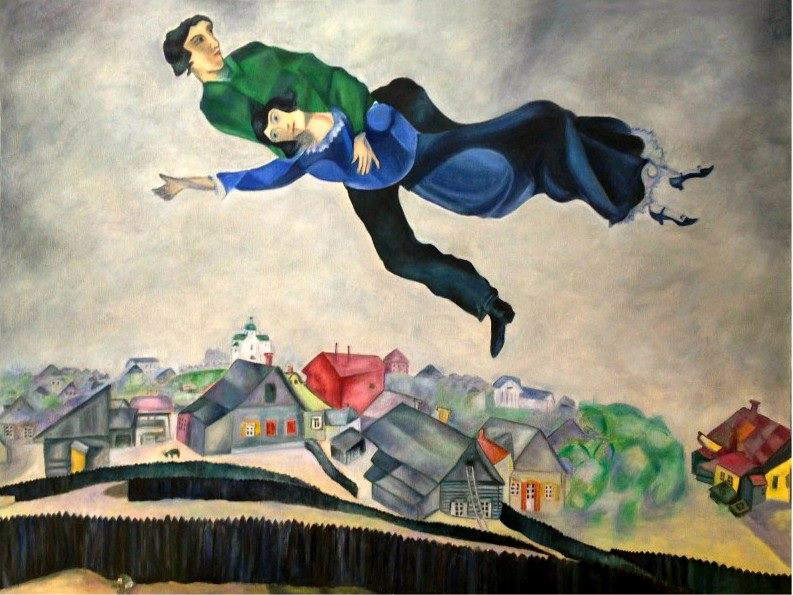

Similarly, one finds the city of Vitebsk and the celebration of the union between the two lovers in the famous work Above the City (1918). In this case, both are portrayed flying over the town, embraced so that the man holds the woman at chest level in a gesture of great tenderness and protection. The view of the town is more realistic than in The Promenade, and again the synagogue is depicted in a different color from the other buildings. Thereafter, Chagall’s style focuses mostly on spots and bands of color that become the protagonists of the canvas and no longer enclosed in the figures that make up the scene. He adapted, in a sense, to the Tachisme (from tache, stain) trend of the artists of the 1950s. A large part of his output in these years was, moreover, devoted to works with biblical themes, a clear legacy of his Jewish training.

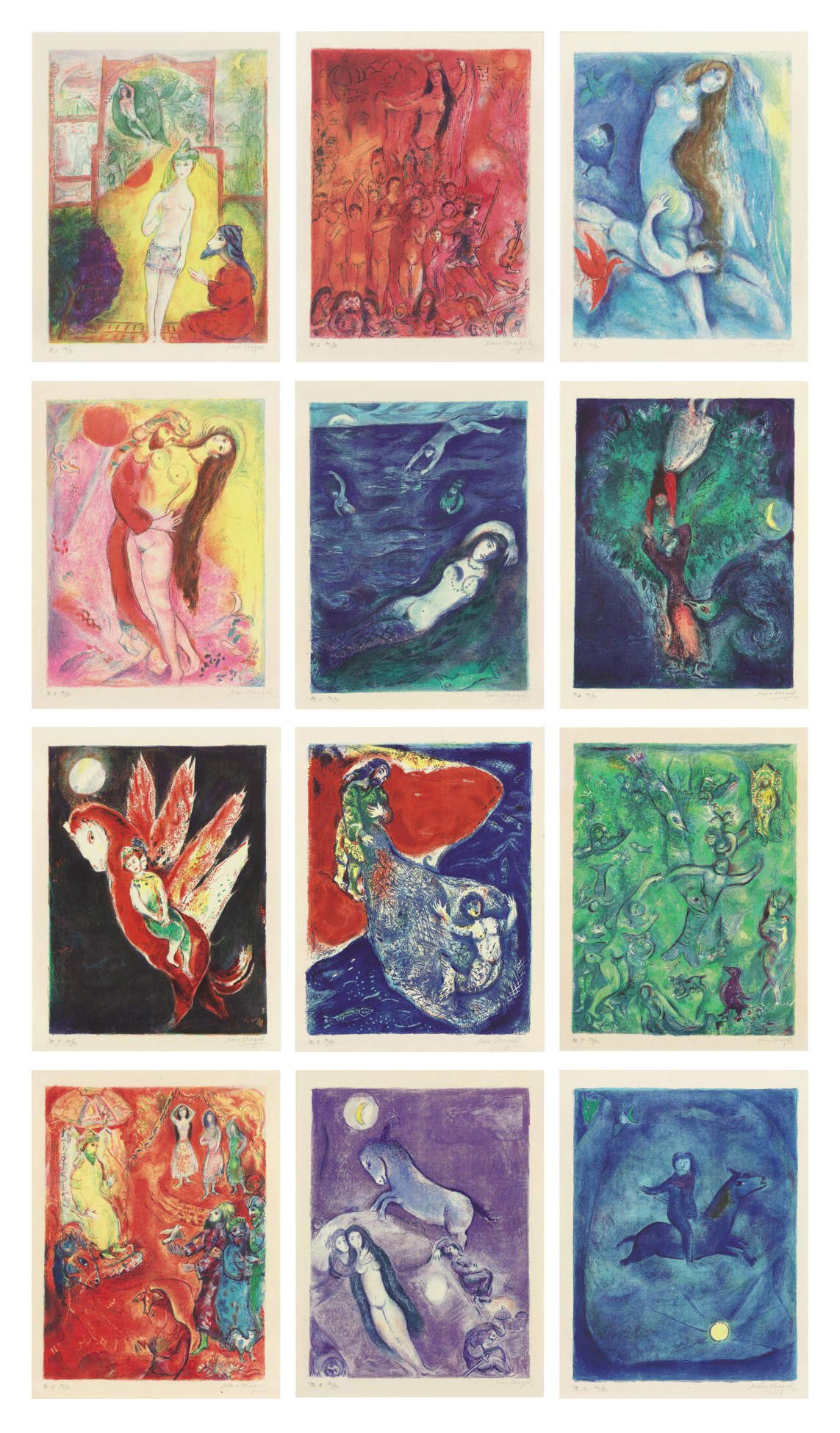

From a young age Chagall was fascinated by the Bible, which he had always regarded as a great source of inspiration, and he began to study it with complete dedication from the 1930s. His first official work was a series of plates on biblical themes commissioned by the French publisher and merchant Ambroise Vollard (for whom he had already illustrated other tomes such as The Dead Souls of Gogol’ and The Fables of La Fontaine). Chagall devoted himself with great enthusiasm to this work for a decade or so, even deciding to take a trip between Egypt, Syria and Palestine to see the places of the stories told up close.

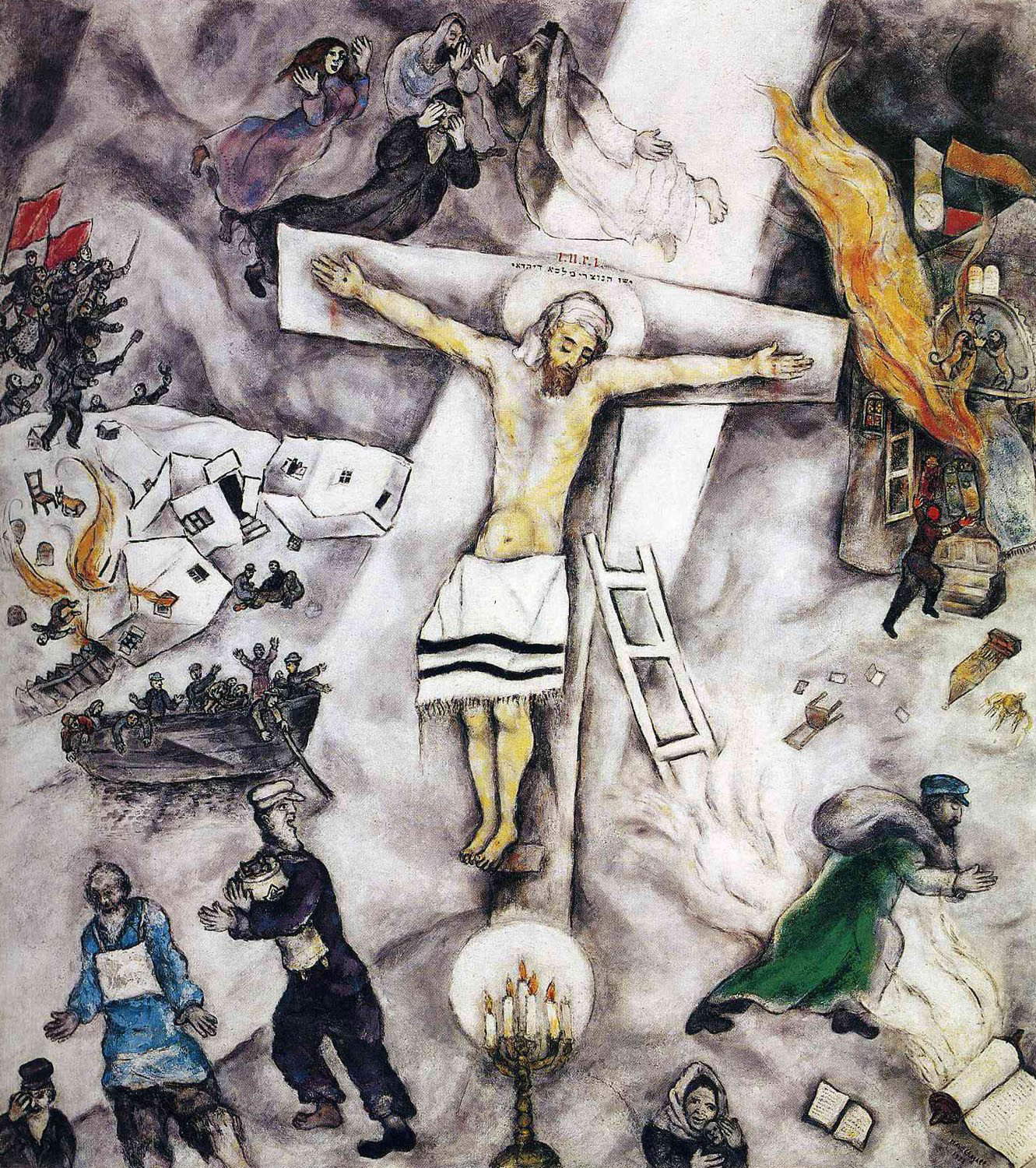

Religiously themed paintings include White Crucifixion (1938). In this case, the scene of Jesus’ crucifixion is used to represent the suffering experienced by the Jewish people due to the persecution they suffered. Christ is placed in the center of the composition, and he wears both the halo (a symbol associated with the Christian religion) and the tallit, the shawl worn by men during Jewish prayer. All around him are depicted scenes of destruction, a way of presenting together both the suffering and injustice suffered, trying to highlight the meeting points of his traditions. The Bible then became the main theme of Chagall’s artistic production, until one of his last works dated between 1963 and 1964, namely the imposing Il ceiling of the Paris Opera, consisting of a series of colorful animals and angels.

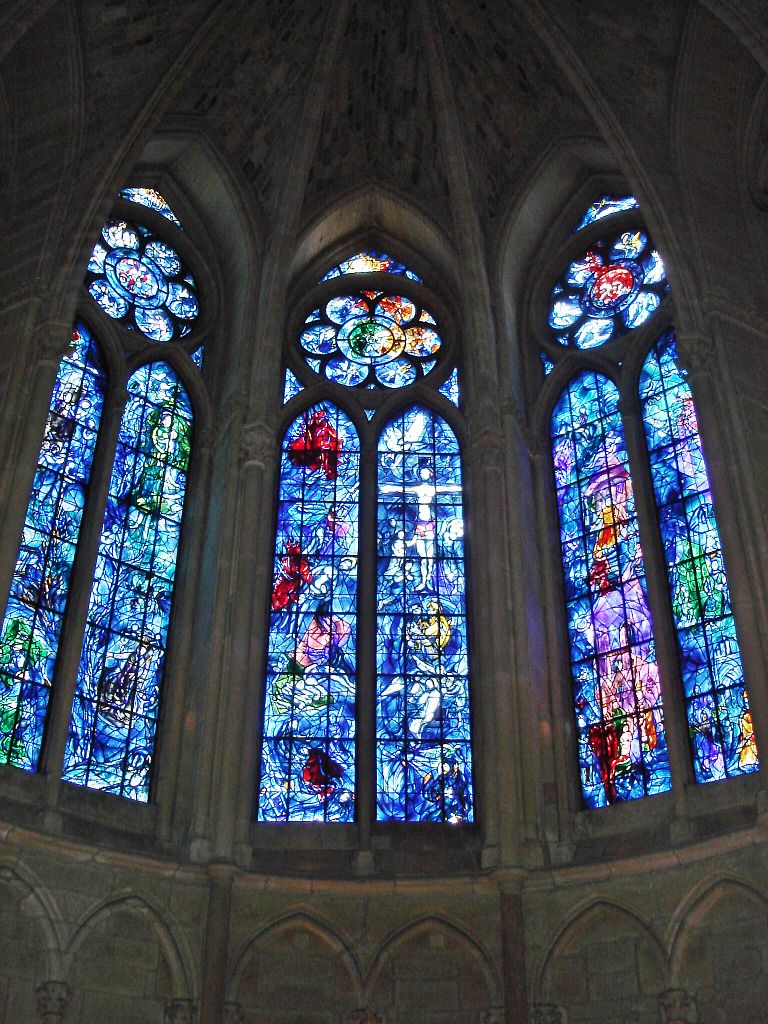

The period he spent in America to escape World War II was very prolific. He obtained numerous commissions, theatrical scripts and produced the famous illustrations for the volume Arabian N ights (inspired by the Arabian Nights). In addition, a meeting in 1951 with Valentina Brodsky (known as Vavà) infused him with new inspiration and artistic sap. She became his new muse of inspiration after the loss of his wife and introduced him to the knowledge ofclassical Greek art. Upon returning to Provence, where, by the way, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse also moved at the same time, Chagall also took up other techniques, such as sculpture, ceramics and glass. In these productions, too, he depicted the elements dearest to him, namely biblical figures, women and animals. Toward the end of the decade he also devoted himself to tapestries and stained glass, which he made for several churches and synagogues in Provence, as well as one with a pacifist theme that he donated in 1964 to the UN in memory of Swedish diplomat Dag Hammarskjöld. Chagall produced other famous wall paintings, for the foyer of the Watergate Theater in London (1949) and for the MET - Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (1966); finally, there are the stained glass windows for the cathedrals of Metz (1959-68) and Reims (1974).

Where to see the works of Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall’s most famous paintings are preserved in major exhibition venues, in different cities. In his native Russia, you can see The Jew in Pink (1915), The Mirror (1915) and The Walk (1918) in the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg, while Above the City (1918) is in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

In the Centre Pompidou in Paris is housed The Wedding (1910). The famous masterpiece Birthday (1915) and I and the Village (1911) are kept in the MOMA - Museum of Modern Art in New York. Also in the United States is White Crucifixion (1938), in the Art Institute of Chicago. Also, in the very city of Chicago he created a mosaic dedicated to the Four Seasons.

Also of note are the murals created for the United Nations headquarters and for the MET - Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York, at the Paris Opera House and the Water Gate Theater in London. In Italy there is a painting by Chagall, specifically in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence entitled Self-Portrait, a work that was donated in person by the artist to the museum in 1976. Numerous other works are held in private collections, and can be seen at exhibitions dedicated to the artist.

|

| Marc Chagall, life and works of the great Russian-French painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.