The season of the Florentine Republic ended in 1512 when the Holy League formed by Pope Julius II promoted the return to Florence of the Medici, who succeeded in restoring the lordship by placing Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, at its head. Giovanni de’ Medici, elected pope the following year as Leo X, left the Florentine lordship in favor of Giuliano de’ Medici, his younger brother. The republicans, however, saw fortune turn on their side in 1527: the new pope Clement VII, born Giulio de’ Medici (he was the son of Giuliano, brother of the Magnifico) allied with France to oust the imperials from Italy. The empire’s reaction was not long in coming: the powerful emperor Charles V sent an army of lansquenets to Italy to attack the Papal States. Despite the fact that the pope’s allies had attempted to hinder the advance of the imperial army, the latter arrived in Rome in May 1527, putting the city to the sword: it was the famous sack of Rome, which also caused the diaspora of the artists present in the city. The republicans then thought that the opportunity was good to drive the Medici out of Florence: they succeeded, but following the reappeasement between Charles V and Clement VII, the imperial troops, in 1530, besieged Florence, conquering it ( Michelangelo Buonarroti also participated in the defense of the city) and causing the Medici to return to the city.

The Medici would then continue to rule over Florence for another two centuries, uninterrupted. The new lord, Alessandro de’ Medici, received the title of duke in 1532, but his rule was short-lived because he died in 1537, assassinated by his cousin Lorenzino de’ Medici. The rule then passed into the hands of Cosimo I, who ruled the duchy (which became a grand duchy in 1569) until 1574. A rather prosperous season opened with Cosimo, characterized by territorial expansion (Cosimo also managed, in 1555, to annex the Republic of Siena to his domains) and the renewed presence of numerous artists in the city.

It was against this backdrop that Mannerism took off. The term maniera was already present in the fifteenth century, but it took on a particular meaning in the Lives of Giorgio Vasari (who, moreover, was one of the principal Mannerist painters): with the locution maniera moderna, the artist and art historian from Arezzo indicated the style of the great artists of that period known to him as the Third Age, that is, what we now consider the mature Renaissance. It was therefore the style of artists such as Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Giorgione. The term Mannerism arose in the 18th century to refer contemptuously to all those artists who, beginning in the first decades of the 16th century, instead of imitating nature, took to imitating the “manner” of the great artists of the mature Renaissance. Today the term has been stripped of the negative connotation it originally had and indicates all those artistic processes that began to detach themselves from the art of the mature Renaissance in order to elaborate new and different schemes from those produced previously, and that in some ways could even constitute an evolution of the Renaissance itself (so much so that it is not uncommon to find, in historiography, scholars who refer to the period of Mannerism by referring to it as late Renaissance).

The first artist to show a notable change in style from his previous experiences, and thus fully Mannerist, was Jacopo Carucci known as Pontormo (Pontorme, Empoli, 1494 - Florence, 1557). A solitary painter with a deeply tormented and bizarre character, methodical and isolated from society to the point of becoming the first painter to embody the cliché of the alienated artist, Pontormo was profoundly marked by the uncertainties and anxieties of the time. Indeed, the political upheavals, wars, and social difficulties of the early 16th century had a great influence on the artists’ production.

Trained in contact with many of the exponents of the mature Renaissance, of whom he was a pupil(Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea del Sarto, Mariotto Albertinelli), Pontormo operated a drastic revision of earlier art, going so far as to firmly deny Renaissance rationality. This tendency of his already emerges from his earliest works, such as the Joseph in Egypt (c. 1518) kept at the National Gallery in London, where different episodes from the biblical story of Joseph are depicted on the same painting without, however, a clear division and without the rules of Renaissance spatiality being respected: this is especially evident if one observes the irrational curved staircase climbing around a building with a circular plan.

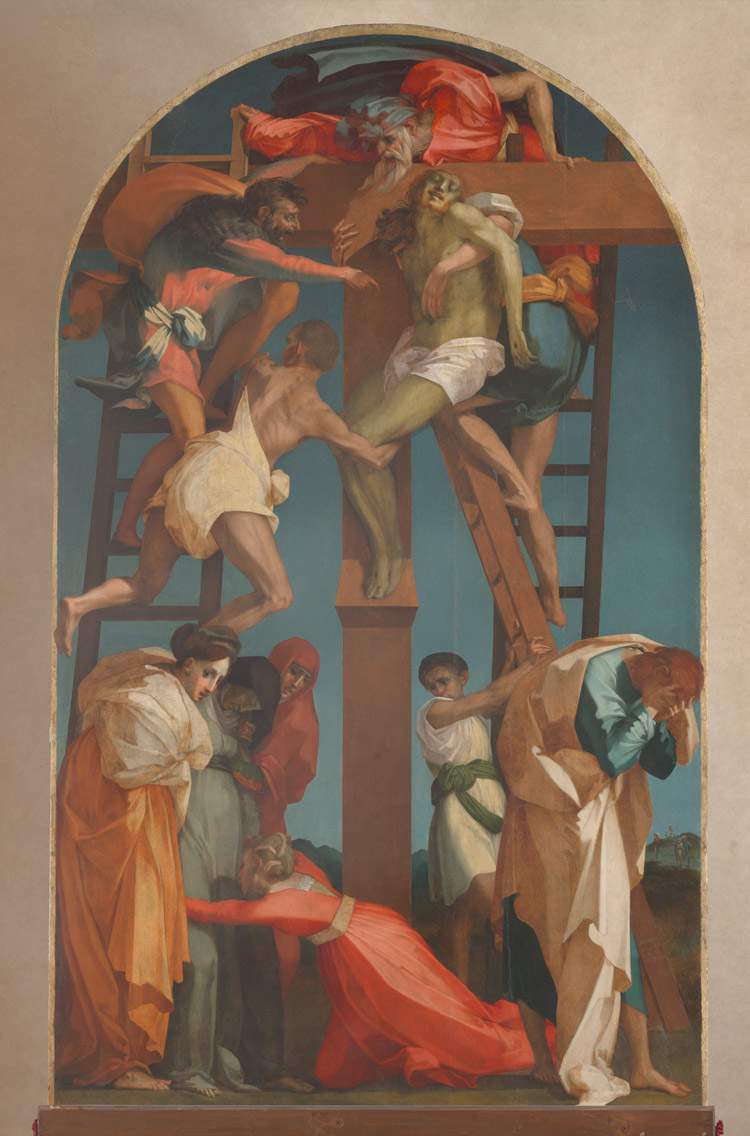

This denial of spatiality reached its climax in what is considered Pontormo’s major work, the Deposition (1526-1528) in the church of Santa Felicita in Florence: a work in which all spatial references are lacking, the bodies seem to float in the sky since they lack footholds or planes of support, and dpve the natural laws of physics are distorted (with one of the characters holding the body of Jesus by simply leaning on the tips of his toes) and the very light, muted colors of the tightly fitting robes, so much so that they seem to be painted directly on the bodies (a specification that would later become a constant in Mannerism), make even the characters seem unreal. The effect of alienation reaches its highest point here.

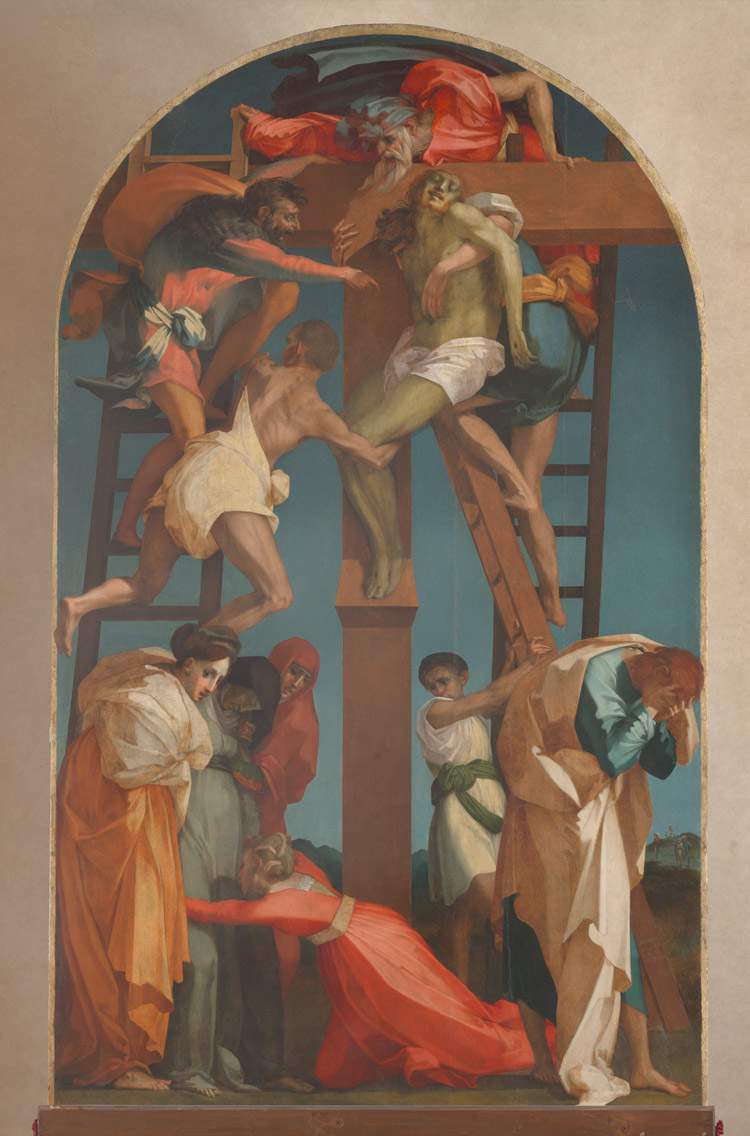

Similarly alienating is the art of the other great Florentine Mannerist of the first generation, Giovanni Battista di Jacopo known as Rosso Fiorentino (Florence, 1494 - Fontainebleau, 1540): endowed with a more open personality than Pontormo, he shared with the Empolese painter, whose age he was, part of his training, as Rosso was also a pupil of Andrea del Sarto. Rosso Fiorentino’s goal was also to upset Renaissance rationality, but he operated differently from Pontormo. If in fact the latter had achieved his goal by denying spatiality and making all rational reference lacking, Rosso Fiorentino on the other hand achieved the effect of alienation by deforming reality in an almost grotesque way: this explains the Deposition (1521) preserved today in Volterra, another great Mannerist masterpiece. In a composition with abstract forms and almost spectral tones (with figures that here too seem to fly since they lack supports), Rosso Fiorentino creates unreal and irrational angular draperies, shapes with unnatural colors, and characters with deformed faces.

This anti-Classicism that Rosso Fiorentino shared with Pontormo is evident in several of his works, such as Moses and the Daughters of Jethro, where in addition to the negation of space typical of the early days of Mannerism we also have the extreme consequences of Michelangeloism, with a tangle of exceptionally powerful nude bodies, and distinguished by angular anatomies, and with faces deformed into grotesque and almost caricatural expressions.

Alongside these two names it is possible to add a third “founder” of Mannerism, but in this case not Florentine but Sienese, namely Domenico Beccafumi (Valdibiena, 1486 - Siena, 1551), who is often considered to be the first artist in whom Mannerist tendencies are manifested, since he was ten years older than Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Beccafumi’s beginnings were characterized by meditations on the mature Florentine Renaissance, particularly that of Fra’ Bartolomeo (whose grandiose monumentality he took up) and Raphael, showing that he reread the great artists of the time according to a new and more restless sensibility.

Beccafumi did not reach the degree of irrationality of Pontormo and Rosso, but his restlessness can be felt in the presence of often grotesque elements and in the disruption of traditional patterns (for example, in the Stigmata di santa Caterina (c. 1515, Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale), the main scene is placed by Domenico Beccafumi in the background) and above all in compositional experimentation. Toward the end of his career, by then in the midst of the Mannerist era, Domenico Beccafumi would create works with an irregular course (such as Moses Breaking the Tables of the Law, 1537-38, Pisa, Duomo) and marked by a certain degree of eccentricity (typical of the artist).

Having exhausted the alienating charge of the early experimenters of Mannerism, the artists of the next generation retained some of the characteristics developed by Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino (such as the muted, almost unreal colors and the extremely tight-fitting garments) and combined them with a broad reflection on the style of the greats of the mature Renaissance (above all Raphael and Michelangelo), each according to his or her own personal interpretation. The main exponents of this almost courtly Mannerism, since it found ample space at the court of Cosimo I, were Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574) and Angelo Tori known as Bronzino (Florence, 1503 - 1572).

Vasari was an eclectic intellectual: he was an art historian (we might call him the father of modern art historiography), painter and architect (in fact, he was responsible for the Uffizi Palace, the artist’s most important public work, commissioned by Cosimo I). Vasari’s painting was directly inspired by Raphael and Michelangelo, with a tendency toward Michelangelo’s plasticism (Vasari was in fact a great admirer of Michelangelo), which was declined in a language that was sure-footed, monumental and highly celebratory(Perseus and Andromeda, 1570-1572, Florence, Palazzo Vecchio). This sense of elevated solemnity that emanates from many of Vasari’s works is obviously due to the fact that for much of his career he found himself working for the Medici court. There was no lack, however, even in Vasari, of a certain taste for complex solutions (as happens, for example, in his Immaculate Conception) that was part and parcel of the mannerist stylistic signature but which in Vasari does not go so far as to result in the bizarre.

A certain taste for the bizarre, on the other hand, was not lacking in Bronzino, an author capable of creating complex allegories (still not fully deciphered today) in works that revisited the mythological and classical repertoire, such as theAllegory (c. 1545) in the National Gallery in London, and which are characterized by cold, diaphanous colors that made his compositions almost abstract. And it was precisely coldness that was the most typical and most immediate characteristic of the art of Bronzino, who was a friend and pupil of Pontormo, but as alienated and isolated as the master was, so open to relationships was his pupil, who became an official painter at the Medici court.

Bronzino’s aloofness is drawn above all from his extremely fertile portrait production: as an official painter of the Medici court, he had in fact been commissioned to paint numerous portraits of family members. The subjects depicted by Bronzino appear impassive, almost abstract, in any case distant from the observer. One can detect in Bronzino a desire for idealization with new intentions compared to those of the Renaissance: it is no longer an idealization aimed at seeking the ideal beautiful, but an idealization that tends to fix the subject portrayed in order to confer immortality on him. That is why in his portraits every flaw is erased. The cold abstraction of Bronzino, among the greatest and most prolific portraitists of his time, was but one way to celebrate the Medici household. The Medici portraits fully responded to the ideals of decorum that had been emerging in the wake of the Counter-Reformation. However, Bronzino was also a painter capable of meticulous descriptions, as is evident in the portrait of Eleonora di Toledo (1545, Florence, Uffizi), wife of Cosimo I, where Angelo Tori astonishes the viewer with an almost tactile rendering of the duchess’s precious dress.

Giorgio Vasari’s friend was another important Mannerist exponent of the same generation, Francesco Salviati (Florence, c. 1510 - 1563), who proposed a powerful and charged classicism that took its cues from Michelangelo but found greater success when the artist left Florence to move to Rome. Despite their power, however, his works did not lack elegance and a remarkable taste for decoration(Incredulity of St. Thomas, 1543-1547, Paris, Louvre).

|

| Mannerist painting in Tuscany: origins and development |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.