Man Ray: life, works and research of the great Dada artist

Man Ray, (Emanuel Radnitzky; Philadelphia, 1890 - Paris, 1976), was a painter, photographer and film director. He is considered a great multifaceted figure, a protagonist of the artistic season of the first half of the 20th century, representative of the American Dada and Surrealist movements. Moving from New York to Paris, Man Ray was among the first to theorize a new language of photography and film, positing them as tools of artistic making.

Photography became a substitute for painting, an extension of figurative art. Man Ray used the photographic medium both in its documentary sense, aimed at witnessing the ephemeral life of his inventions and “objects of affection,” and in its more creative sense, which makes the technique capable of inventing a new world of images. His understanding of the photographic device is well rendered by what he used to say, “I paint what I cannot photograph. I photograph what I do not want to paint. I paint the invisible. I photograph the visible.”

Life of Man Ray

Emanuel Radnitzky, better known as Man Ray, was born in Philadelphia on August 27, 1890 to a family of Jewish descent. At the age of seven he moved to New York City, where he spent his adolescence. City life was instrumental in his progressive approach to art, stimulating his interest in pictorial media, which became increasingly pronounced. At the age of fourteen, two high school teachers pushed him toward this natural inclination, so he practiced a great deal in freehand and technical drawing. Man Ray thus acquired an important skill in architectural drawing, providential when he won a scholarship in architecture at New York Univeristy in 1920. Despite this, the artist soon abandoned his architectural studies, not having sufficient interest in them.

Rather, he did any job, from newsagent to draftsman in an advertising firm, or draftsman in an atlas and map publishing house. Experiences that helped him learn various graphic design techniques. He attended courses at the evening art institute at the Francisco Ferrer Social Center, also in New York: the ideas of the environment he found there met Man Ray with full sympathy. The pedagogue Francisco Ferrer said that he “needed men who were capable of unceasing development, of renewal, strong in their intellectual independence”: this was exactly what Man Ray’s life was, that is, uninterruptedly directed toward the search for new means of expression. For this reason, the artist always knew how to renew himself.

By the time he was in his twenties, his encounters with already established painters such as Robert Henri and George Bellows left a decisive imprint on Man Ray, who broke free from the more conventional artistic rules and traditions, convincing himself more and more to rely on his own imagination, on his being bold and independent, committing himself not to be afraid of his own initiatives. In fact, Man Ray already boasted great technical skill: he was able to paint portraits in half an hour, as early as 1909, as evidenced by the conventional Portrait, but also to make assemblages, such as Tapestry, from 1911. The first works of the 1910s were exhibited precisely at the art institute, the Francisco Ferrer Social Center, where the painter showed great expressiveness and stylistic maturity.

On February 17, 1913, the International Exhibition of Modern Art, known as the Armory Show, opened, the first public presentation of the most advanced European art. For Man Ray, this occasion was a new starting point, briefly introducing him to Cubist modes of painting; more importantly, the contacts he found there served to confirm the direction he had taken. In 1915 his friendship with artists Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia was instrumental in the development of his artistic perspective. In 1916 Man Ray began experimenting with areograph painting, a new technique that he added to his collage and assemblage production. In the same year he began to weave contacts with the rampant Dadaist movement, which had sprung up at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916 and arrived with little delay in America as well. Two events in particular marked Man Ray’s growing participation in avant-garde activities.

In 1916 he founded, together with Marcel Duchamp, the Society of Independent Artistis; he then showed at the Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters, at the Anderson Galleries, with Invention Dance. In the exhibition catalog, a statement by Man Ray emphasizes the supreme importance he attached to intelligence and imagination. In 1917 Man Ray painted what were for a long time his last oil paintings, Coffee Machine and Narcissus being the most notable.

His growing friendship with Marcel Duchamp led him toward an increasingly resolute reluctance to devote himself exclusively to painting: “I longed to find something new, which would allow me to do without an easel, paints and all the other paraphernalia of the traditional painter. When I discovered the airbrush, it was a revelation: it was magnificent to be able to paint a picture without even touching the canvas; this was a pure cerebral activity” (Man Ray).

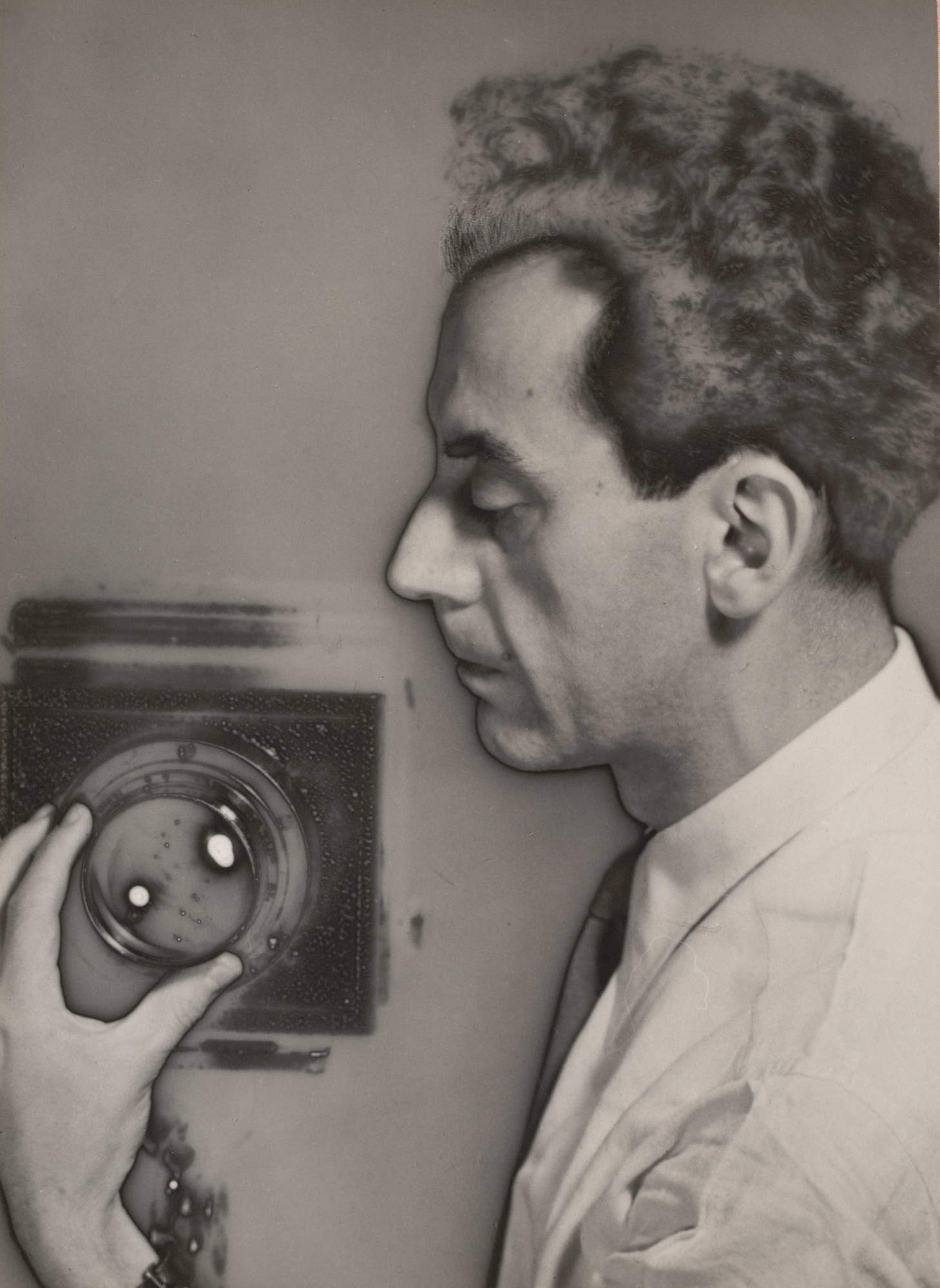

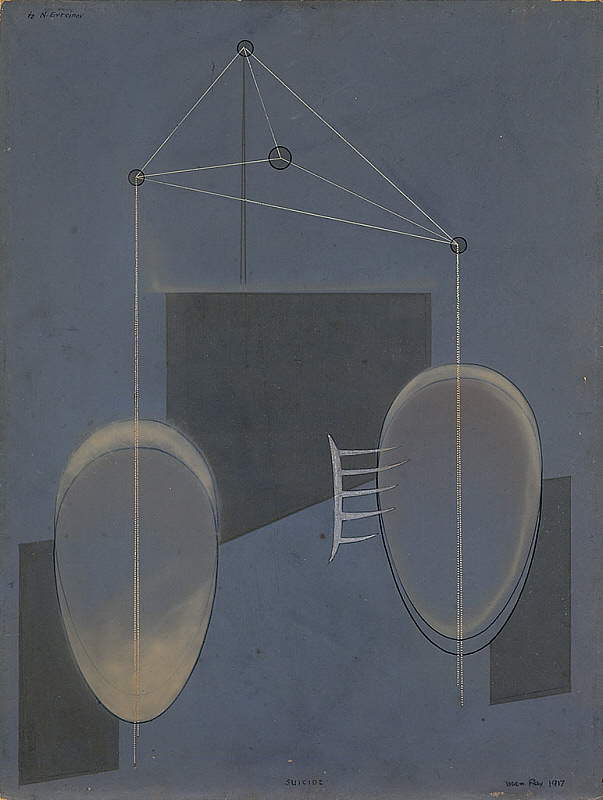

The criticism he received following his first two solo exhibitions at the Daniel Gallery (1915) was very harsh and hostile. To testify to this suffering spiritual crisis he made Suicide in 1917. Between 1918 and 1922 was a short period in which the artist resumed an intense research: it was a time when he felt very free and directed his efforts in trying to break away from painting. Meanwhile, New York Dadaist activity revolved mainly around him: together with Duchamp he published “New York Dada” in 1921, but he tended to perceive himself only in this experience. Only he American, while Duchamp and Picabia were French. Since America tended to alienate whatever did not present itself as an American product and, consequently, to distrust Dadaist language, Man Ray understood that "Dada cannot live in New York." He also understood that it was time to move so that he could continue to grow as an artist in the way he desired. Duchamp left for Europe in early 1921, and Man Ray did not hesitate to follow him. In Paris he was preceded by a reputation as a defender of the Dada spirit in New York, which is why the Dadaists were ready to welcome him. He landed in Le Havre, Normandy, in July 1921, ready to follow the iconoclastic revolution that had already been underway for three years. Soon thereafter, in 1924, essayist André Breton would publish the first Surrealist manifesto. Man Ray therefore arrived in France that Dadaism was nearing its end and Surrealism was crystallizing around Breton’s milieu: in this entourage, he became the first Surrealist photographer.

Also in 1921 Man Ray held his first exhibition at Librairie Six, owned by writer Philippe Soupault. There he exhibited the famous work Cadeau, now in a private collection. But what followed were difficult times, a period of crisis for the avant-garde in general. Man Ray began to turn to photography to earn a living: he achieved great success in Paris thanks to his skill as a photographer, especially as a portraitist. Very prominent artists at the time posed in front of his lens, including Gertrude Stein, the famous writer and art critic.

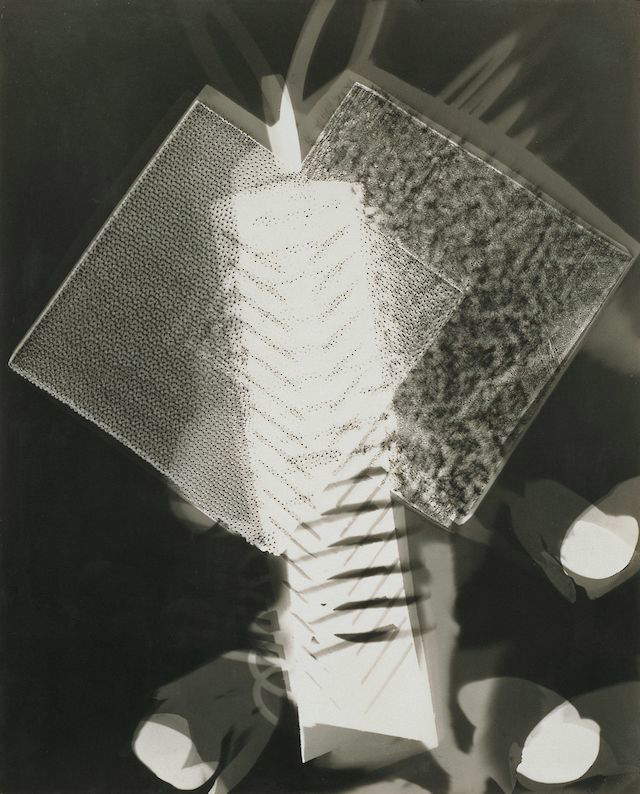

In the field of photography, too, he could not resist the temptation to “renew himself,” so he experimented: in 1921 he invented rayography, a photographic process discovered by chance, which was achieved by direct contact on sensitive film, without the need for a camera. Throughout the decade from 1920 to 1930, Man Ray focused on photography and the “objects of fondness” he created with the aim of using them as pretexts for unconventional photographs. In 1925, he presented at the first Surrealist exhibition at Galerie Pierre in Paris along with artists Jean Arp, Max Ernst, André Masson, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso.

Despite his commitment to photography and objects, Man Ray did not fail to always carve out a couple of hours a day to devote to painting. With the success he achieved around 1929, he used to paint in the morning and photograph in the studio in the afternoon. The most significant Parisian paintings were produced in two short periods, 1932-24 and 1938-39. In the mid-1930s he also devoted a lot of time to drawing, an activity he loved and as he himself had to say, “In these drawings my hands dream.” Les mains libres is a 1937 publication in which the most Surrealist dream drawings are collected.

Man Ray illustrated dreams that in some cases even turned out to be premonitory: the one of September 3, 1936, in the background features a clock indicating three o’clock. Exactly three years later, on September 3, 1939, World War II broke out. Precisely because of the conflict, Man Ray had to flee Paris in 1940 because of the anti-Semitic nationalist movements that began to spread throughout Europe.

For this reason he returned to New York, in particular he moved to Los Angeles where he taught photography and painting in college, without completely interrupting his artistic production. When the war ended, he returned to Paris, continuing to paint and photograph. He returned to America occasionally, was in Italy in 1975 to exhibit his photographs at the Venice Biennale. But his home was in France, in the Parisian neighborhood of Montparnasse, where he settled until the last of his days on Nov. 18, 1976. His epitaph, now in the cemetery in the same neighborhood, reads “Unconcerned, but not indifferent.”

Man Ray,

Man Ray,

Man Ray’s major works and style

In 1908 Man Ray was greatly impressed by the sculptor Auguste Rodin’s watercolors, which he had the opportunity to see exhibited at 291 Gallery in New York. He found there the freedom he was seeking for his own artistic expression. Much the same happened in March 1911, when he saw the watercolors of Paul Cézanne, which also fascinated him. Man Ray also looked to the Old Masters: Rembrandt, Frans Hals. But from all of these artists, while admiring their genius, he drew little influence, as his admiration never translated into a desire to imitate them, but regarded them solely as ideal models to be inspired by.

From the forms of Portrait, a 1909 painting in which he followed the more academic dictates, he soon moved away. Already in 1910 he had distanced himself widely from them in Still Life with Teapot. The direction he took led him to try his hand between collage and assemblage: he thus produced his first abstract work, Tapestry, in 1911, composed of canvas samples from the tailor’s shop where his father worked. Determined to pursue in his departure from the medium of painting, he came to devote himself to the study of other tools, including the areograph: by focusing on this medium, he created a physical distance between the tool and the canvas. It was something he always tried to do, capturing a metaphysical essence without resorting to direct contact.

In 1917 he made Suicide, to refer to the spiritual crisis he suffered after the failure of the American exhibitions. Suicide is a work that also invokes a performative dimension: He mounted the canvas on an easel and placed a rifle behind it, pointed at the canvas. Man Ray would stand in front of the easel, pulling a string that would activate the trigger, in a confrontation with the theme of suicide, always much investigated by artists of the time. In 1918, still by means of the areograph, he composed The Dancer on the String Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows. Man Ray’s passion for jazz and the musical was reflected in 1919 with works such as Jazz and Seguidilla, a Spanish musical.

In his spasmodic search for alternative media to loosen even more contact with painting on canvas, he bought his first camera in 1914. Here again he resolved to become an experimenter, a pioneer, revolutionizing the way of thinking about photography. He thus took photographic portraits of various artists in the milieu he frequented while still in America. Around 1920 he immortalized his friend Marcel Duchamp, disguised as Rrose Sélavy. In these shots the figure of Duchamp is annulled and multiplied in his own identity. The portrait is denied the traditional celebratory function of the person. It was an artistic collaboration between the two friends that at the time expressed a great fellowship: Duchamp’s art was immortalized by Man Ray’s photographs, a necessary artistic medium for Duchamp’s idea.

The friendship between the two artists, which began in 1915, evolved into a lasting relationship that had natural influences in the work of Man Ray, who headed toward the conception of what he would call “objects of affection” from 1917 onward. The poetics of the Duchampian ready-made reverberates in these creations, though, in this case, it is tampered with by the artist.

In 1920 he made an enclosure secured with ropes and knots: this conceals in mystery the objects contained in it. Man Ray called it Isidore Ducasse ’s Enigma, a title that refers to the poet Lautréamont (1846-70), precisely the pseudonym of Isidore Lucien Ducasse, a character beloved by the Dadaists for the ambiguity of his aphorisms: “As beautiful as the chance meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.” Through the title, Man Ray challenges the viewer to trace this aphorism, barely allowing glimpses from the envelope of forms traceable to an umbrella and a sewing machine. Cadeau, 1921, was an “object d’affection” exhibited at Librairie Six in Paris. It is an iron rectified by a row of nails welded to the plate. With this modification, the object becomes completely unusable, deprived of its functionality.Man Ray plays on this aspect, intervening on the object and creating its dysfunctionality with a little intervention. Unlike his friend Duchamp, he makes objects that are almost always manipulated, twisting their meaning and nature with ironic inventiveness. By creating a contamination between serial product and artwork, he stimulates reflection in the audience through an enigmatic component.

This aspect is also found in his rayographs, photographs obtained not by using a camera, but by placing various objects on photosensitive paper and exposing them to light for a few moments. The resulting photographs in this way retained only the outline of the object, its trace, creating ambiguous compositions. Untitled, from 1923, is one of the rayographs preserved at the Guggenheim in Venice.

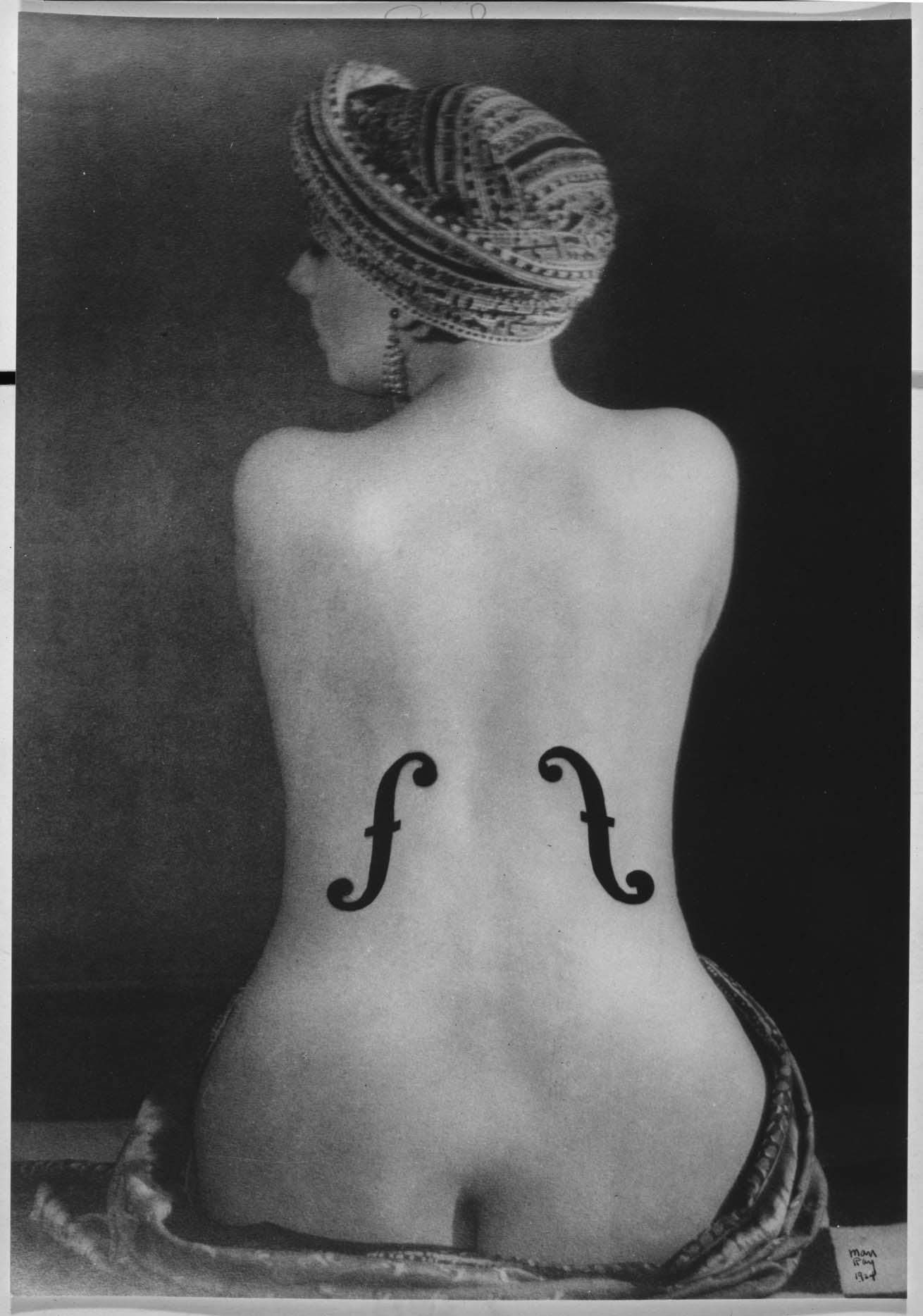

Man Ray continued to explore the world of the photographic specific, becoming increasingly appreciated in his gifts as a portraitist. Having fallen in love with Kiki de Montparnasse, a famous Parisian model, he took hundreds of photographic portraits of her. The best known was Violon d’Ingres, in 1924, which opened the Surrealist season.

He took portraits of other protagonists of the same cultural milieu: writer Ernst Hemingway and writer Nancy Cunard, artists Pablo Picasso, Tristan Tzara, Salvador Dali. Wonderful photographic portrait of collector Peggy Guggenheim.

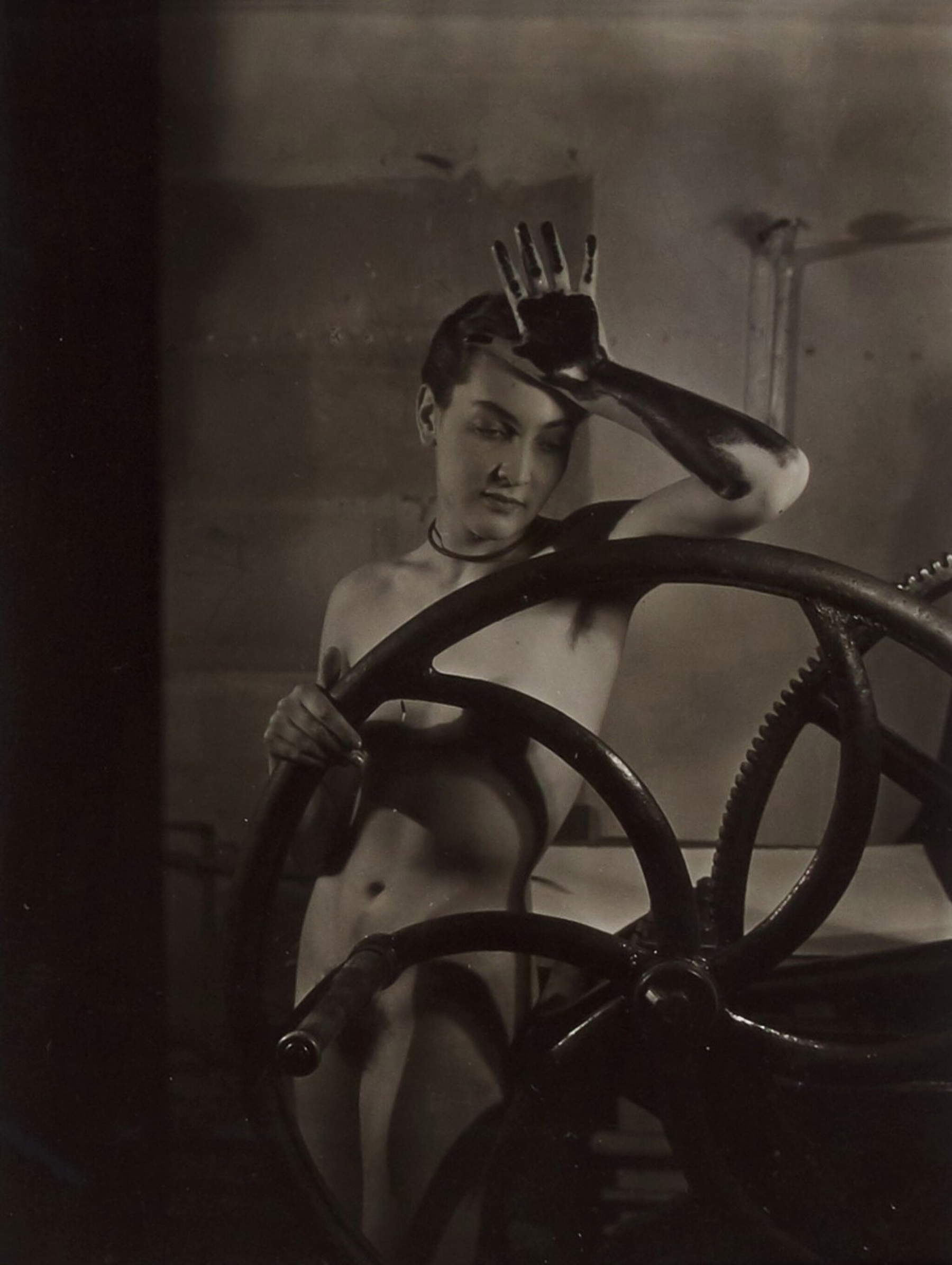

In 1934 he made a series of photographs of Meret Oppenheim, also an artist who was part of the circle that gravitated around André Breton: the famous photographic portrait that Man Ray took of her, Meret Oppenheim with a printing press, gave her the appellation of muse of the Surrealists. The shot - taken in the studio of painter Louis Marcoussis and published in the fifth issue of Minotaure magazine in 1934 - depicts the naked woman, her forearm smeared with ink, in front of the wheel of the printing press.

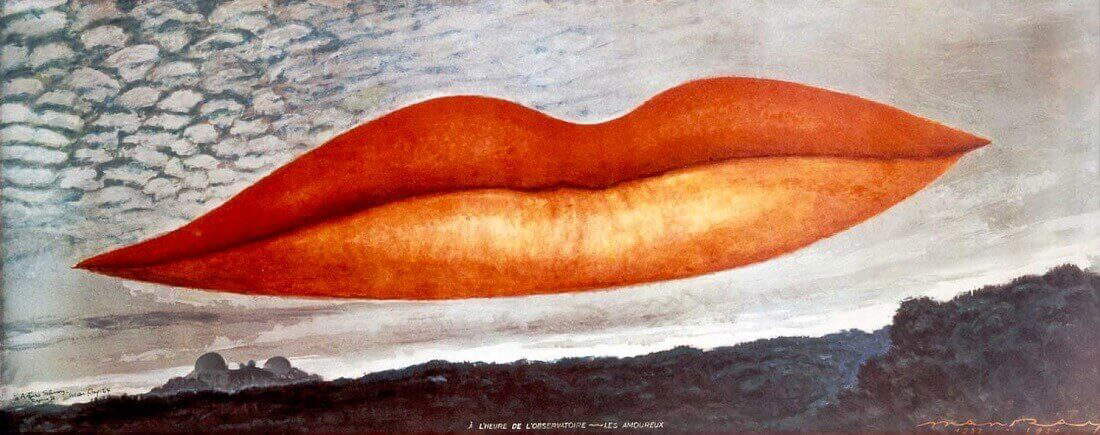

Man Ray became famous for these surrealist shots, but he also produced significant paintings in two short periods spent in Paris (the first between 1932-1924 and the second between 1938-1939). At the Observatory Hour-The Lovers, is one of the most remarkable, a painting inspired by a mundane fact, the perfect imprint of Kiki’s red lips on his white collar.

In his artistic experience, stimulated by an environment so rich in opportunity, Man Ray also explored the field of filmmaking. L’étoile de mer is a 1928 film with which the artist attempts to construct a poetic work by means of an image sequence. The film’s protagonists include the muse Kiki de Montparnasse. Although made at a time when film research was following in the surrealist footsteps of Salvador Dali and LuisBuñuel, Man Ray recalled the Dada season by inserting puns between the sequences(Si belle! Cybèle?), as if to instill the playful sense he so enjoyed.

![Man Ray, Enigma by Isidore Ducasse (1920 [1971]; wood, fabric, rope, cardboard, metal on paper, and invisible object; Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beunigen) Man Ray, Enigma by Isidore Ducasse (1920 [1971]; wood, fabric, rope, cardboard, metal on paper, and invisible object; Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beunigen)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/fn/man-ray-enigma-di-isidore-ducasse.jpg)

![Man Ray, Cadeau (1921 [1972]; iron and nails, 17.8 x 9.4 x 12.6 cm; London, Tate Modern) Man Ray, Cadeau (1921 [1972]; iron and nails, 17.8 x 9.4 x 12.6 cm; London, Tate Modern)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/fn/man-ray-cadeau.jpg)

Where to find Man Ray’s works

In Italy, at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, a photographic portrait of Nush Eluard, made in 1934 using the solarization technique, is preserved. At the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice there is Untitled from 1923, one of the earliest rayographs, and also a fine portrait of the collector herself, Peggy Guggenheim. Tapestry of 1911 and Suicide of 1917 are in Paris at the Centre Pompidou, as is the famous portrait of Kiki in Violon d’Ingres (1924).

Much of the artist’s work is in America: Cadeau (1921) is in a private collection in Chicago. Seguidilla (1919) is at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC. Duchamp’s portrait of Rrose Sélavy as Rrose Sélavy is at the Philadelphia Museum Of Art, in the White Collection; the Surrealist photograph depicting Meret Oppenheim is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The painting At the Observatory Hour-The Lovers is in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

|

| Man Ray: life, works and research of the great Dada artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.