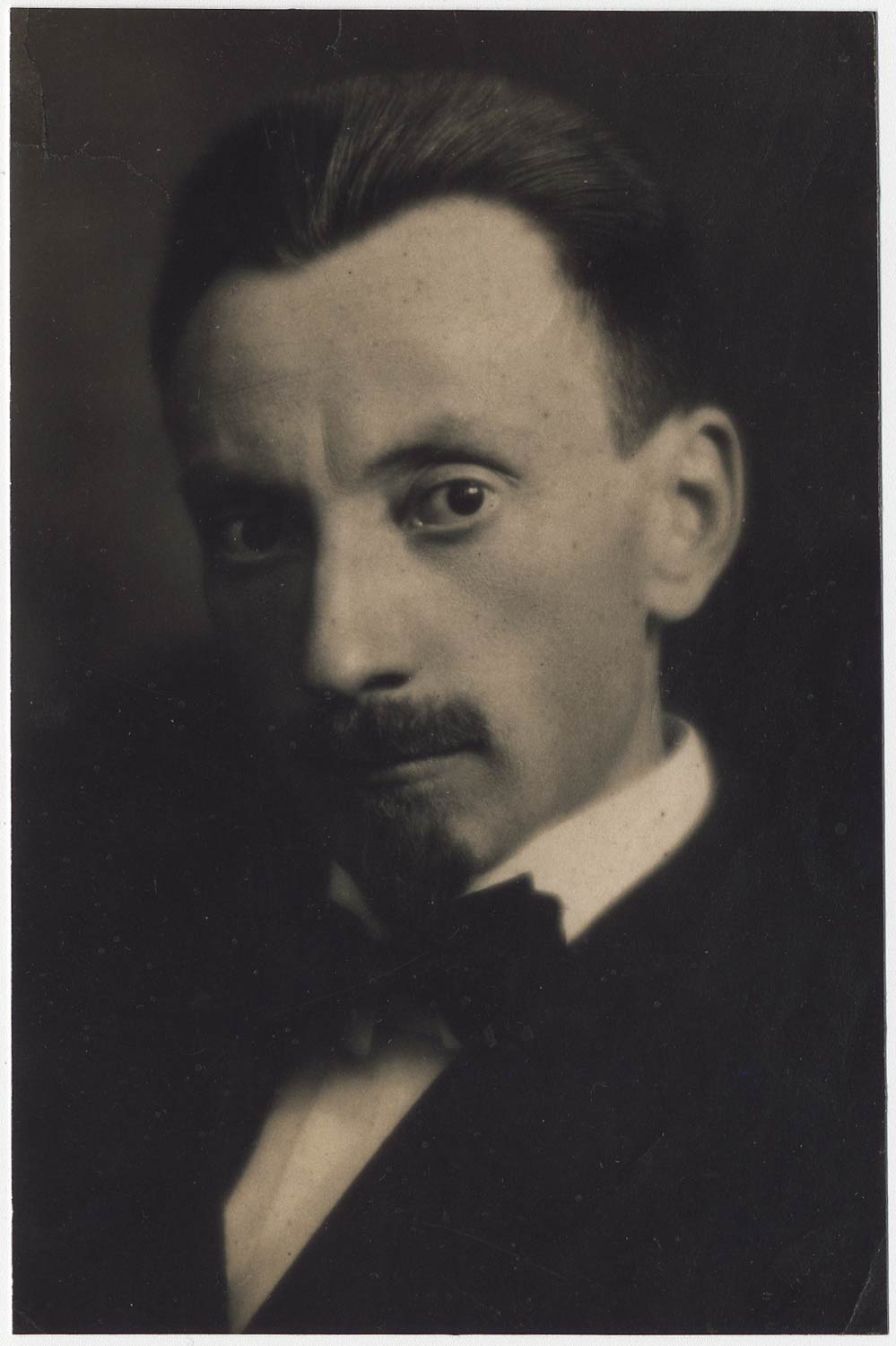

Luigi Carlo Filippo Russolo (Portogruaro, 1885 - Laveno-Mombello, 1947), painter, composer and inventor of musical instruments, was one of the leading exponents of Futurism: his name appears among the signatories of the Manifesto of Futurist Painting and the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting. His pictorial elaborations are not in large numbers, as for a long period he devoted himself exclusively to music, a field in which he tried his hand at an early age. Russolo, in fact, came from a family of musicians, and his contribution in the field of composition was decidedly innovative, introducing noises as a musical element and dodecaphony and making novel musical instruments that he called Intonarumori.

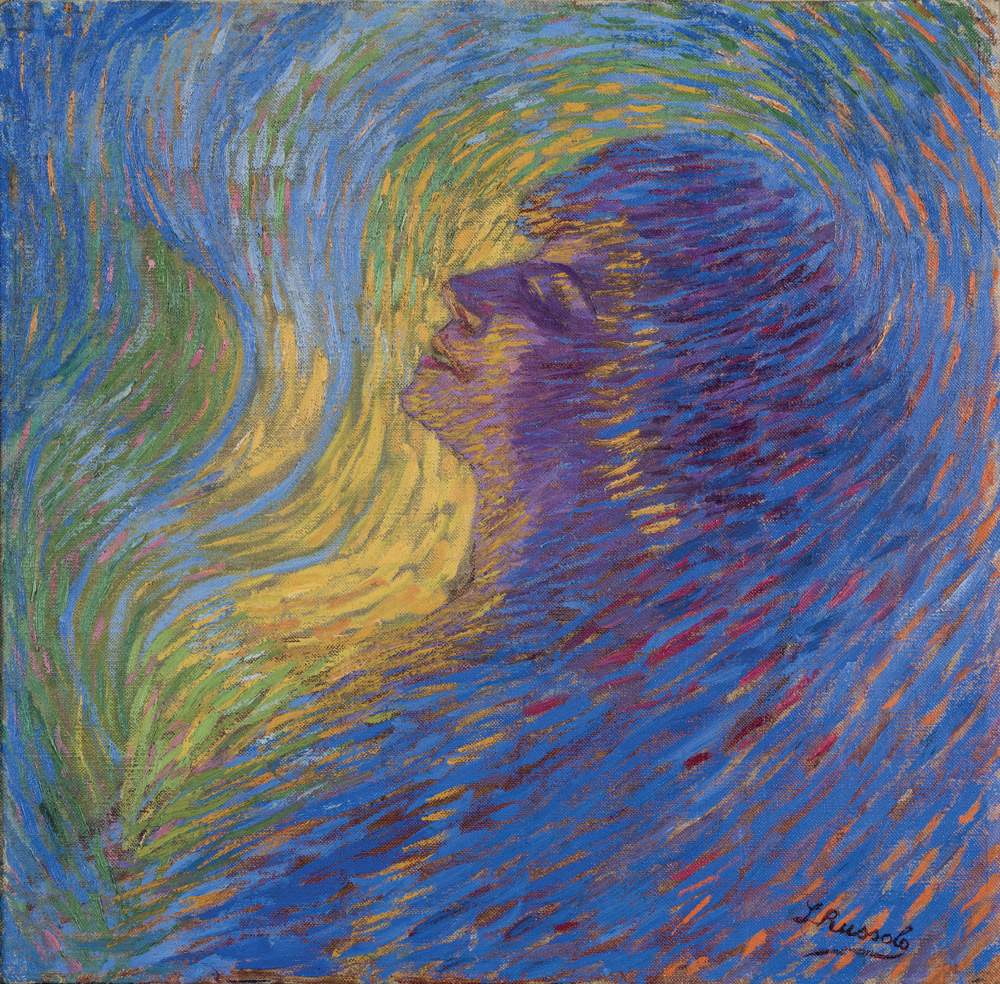

Russolo’s paintings initially ranged between Symbolism and Divisionism, later assimilating the Futurist dictates of decomposition and interpenetration of planes. In addition, Russolo studied the movement of people and machines, in affinity with the research of Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni, with whom he established a confidential relationship. In the last phase of his painting, he landed on landscape representations with obvious philosophical and spiritual influences, which he had embraced in his life.

Luigi Russolo was born in Portogruaro, near Venice, on April 30, 1885. He was the penultimate of five siblings born from the union between his father Domenico, a watchmaker as well as organist of the town’s cathedral and director of the Schola Cantorum of Latisana, and his mother Elisabetta Michielon. After attending high school gymnasium, in 1901 Russolo followed his two older brothers, Giovanni and Antonio, both students at the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory, to Milan. From an early age Russolo had been interested in music, a passion widespread in his family, and once he grew up he also became interested in painting. In Milan he took some courses at theBrera Academy and worked as an apprentice during the restoration of the decorations of the rooms of the Castello Sforzesco and Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. In 1909 several important events occurred in Russolo’s artistic career. In this year he produced his first works, participated in the annual Black and White Exhibition at the Famiglia Artistica in Milan, and through this occasion met the Futurist painters Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà. They became close friends and together with them, and other artists, he had the opportunity to meet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the progenitor of Futurism, in person in February 1910. Thus, his entry into the movement officially took place, and Russolo began to be present at all Futurist evenings and exhibitions, both in Italy and abroad. However, after painting several Futurist works, for a long period Russolo abandoned art, preferring to devote himself completely to music.

In 1913 he drafted the Noise Manifesto, in which he theorized the use of noises for musical purposes based on some experiments he used to devote himself to, in the midst of the futurist climate. The twentieth century, after all, thanks to the development of industrial society was characterized by an increasingly widespread use of machinery that punctuated daily days with their noises, not to mention then the invention of the automobile. Russolo, in the first lines of the Manifesto, explained precisely how up to that time men’s lives had been conducted “in silence or mostly in silence,” and how music, on the other hand, had adapted to the novelties, veering toward polyphony and seeking increasingly complex and dissonant structures and chords. What’s more, Russolo invented new musical instruments that he built by his own hand, to which he gave the name Intonarumori: these were machines that could reproduce sounds of various kinds (bangs, bursts, laughter, rustles and so on) and modify them at will by turning a crank.

Russolo often organized the “noisemaker concerts,” which, however, did not arouse much appreciation among the audience, who also protested vociferously by throwing objects at the musicians. He caused a sensation with the Gran concerto futurista per intonarumori in 1914 at the Teatro Dal Verme in Milan, in which he put together an orchestra for 18 intonarumori, however, encountering a rather violent reaction from the audience amid whistles, shouts and various scuffles, until the police intervened. Russolo, in any case, replicated the concert in Genoa and London, coming to know Igor Stravinsky.

Like other exponents of Futurism, including Boccioni, Antonio Sant’Elia, and Mario Sironi, Russolo in 1917 became involved in wartime turmoil and enlisted in order to participate in World War I. He joined the Lombard Volunteer Cyclist Battalion and was seriously wounded at Malga Camerona on Mount Grappa. He returned home for treatment and spent nearly two years in various hospitals between Naples, Genoa and Milan, a period he spent with much inner turmoil. Once cured, the artist returned to playing music, building musical instruments and painting, participating in the Great National Futurist Exhibition in 1919, and again in 1920.

When Fascism began to gain an increasing foothold in Italian political life, Russolo decided not to join it and was thus excluded from the Futurists, with whom, however, he later reconnected through the intercession of Enrico Prampolini. His music was used for three Futurist films, in which he also appeared as a protagonist. In 1926, marked by economic difficulties, Russolo began working as a laborer, and in the same year he married an elementary school teacher named Maria Zanovallo. He continued to exhibit his work throughout the 1920s, and in 1930 he joined the Cercle et Carré collective. Around 1929, Russolo befriended an Italian scholar of occult sciences in Paris, and through this acquaintance he became interested in Eastern philosophies and practiced yoga. He died in Laveno Mombello, near Varese, on February 4, 1947, three years after his friend Marinetti for whom he had delivered the eulogy.

Luigi Russolo’s pictorial debut at the 1909 Famiglia Artistica Milanese exhibition consisted of a series of etchings heavily influenced by Symbolism. This is evidenced by the work Self-Portrait with Skulls (1909), in which the painter is portrayed with a distraught expression while surrounded by a series of skulls looking at him, hinting at the artist’s awareness of human mortality and how life is full of futility, which becomes nothing after death. Present at the exhibition was Umberto Boccioni, who sensed Russolo’s talent and suggested to him a reflection on his own style and quest for modernity. The later works actually reflect the cues that emerged from his frequentation with Boccioni, and mostly consist of etchings with figures of his mother and sister, along with landscapes of industrial suburbs.

Russolo’s name appeared shortly thereafter among the signatories of both the Manifesto of Futurist Painting and the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting, drafted within a day of each other in 1910, along with Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà and Gino Severini. The two manifestos, the first theoretical and the second containing dictates on the style and technique to be followed, are regarded as milestones of Futurism in painting and some of the most decisive proclamations of modernity in art. Indeed, the manifesto was based on the concepts of the rejection of “passatism” and the exaltation of modern novelties. He also signed the manifesto Contro Venezia Passatista drafted in the same year by Marinetti. Russolo, from then on, participated in all the Futurist Evenings and exhibitions of the movement, both in Italy and abroad.

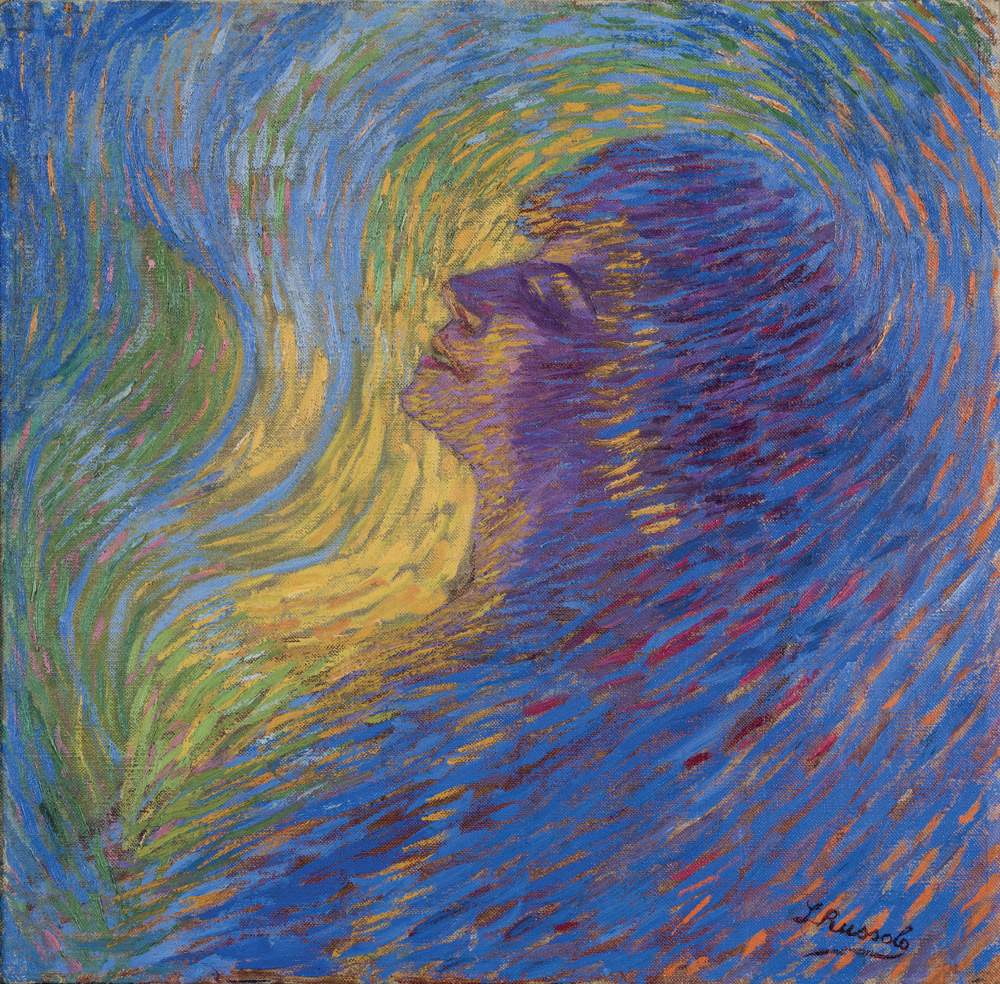

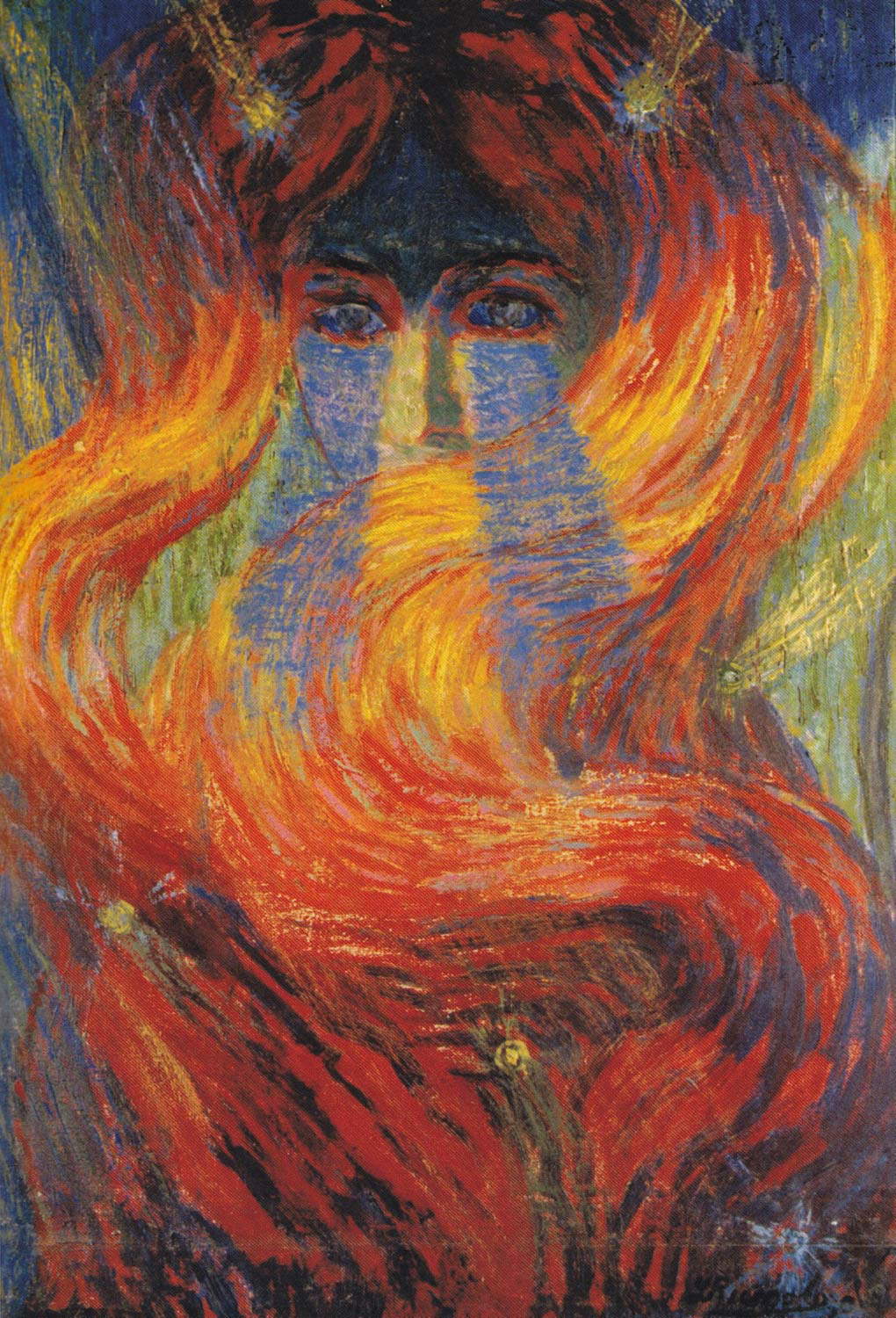

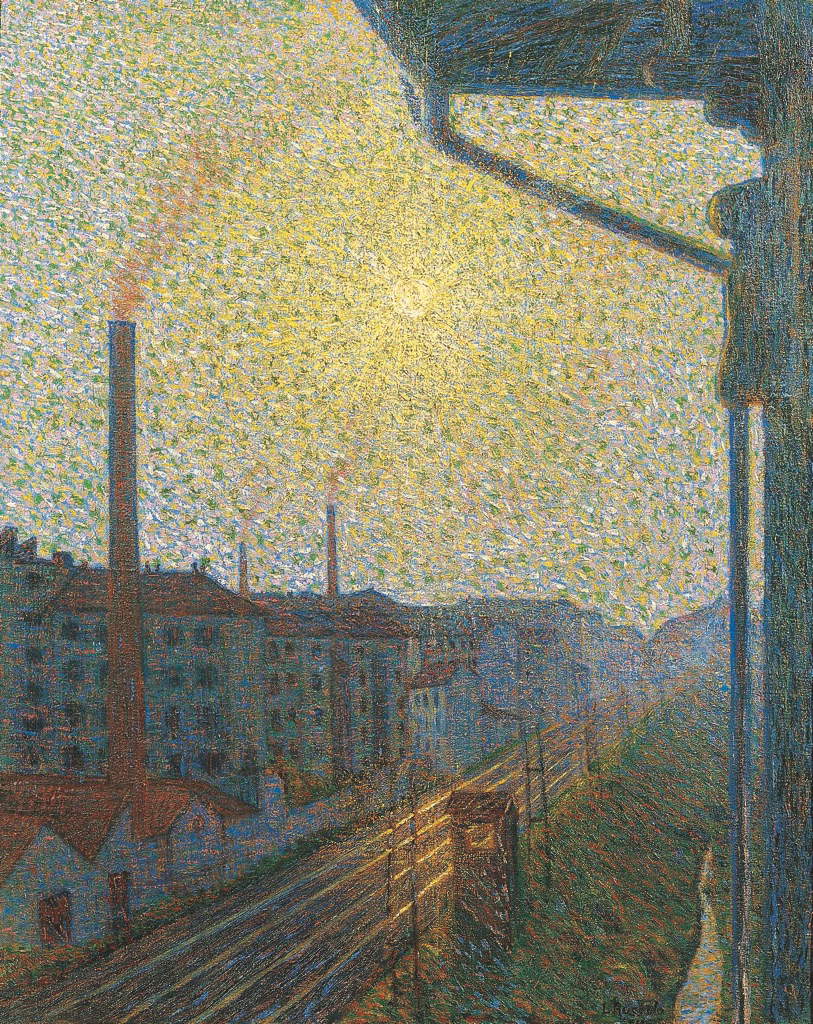

It was precisely in 1910 that Russolo signed one of his most famous works, Perfume. The painting is the obvious result of extensive research aimed at engaging the viewer not only with sight, but also with the other senses. Indeed, looking at it, one has the sensation of perceiving the same perfume that intoxicates the protagonist, through the expedient of the wave created with filaments of color. A solution that can be found precisely in the early works of Boccioni and Balla. A very similar approach is found in Chioma . This work derives from some engravings dating back to 1906 in which Russolo had portrayed his 15-year-old sister Tina, and in the version made on canvas they permeate Symbolist elements, evident in the woman’s eyes from which beams of light come, while to render the waves of her hair he uses the now customary filaments of bright colors. Also from the same period are Periferia-lavoro (1910), and the series of three large paintings Lampi (1910), in which the industrial suburbs, with its smoking smokestacks and street lamps artificially illuminating the scene, are the protagonists.

Revolt (1911) is another experimental painting by Russolo, in which the energy released by a group of people participating in a demonstration propagates throughout the city in the form of geometric lines resembling arrows, a symbol of speed and strength. The same way of expressing the propagation and spreading of something powerful is found in The Music (1911). Here, the sound from a piano becomes a wave that reaches a series of faces reminiscent of theatrical masks, smiling but at the same time almost disturbing. Also recurring in this painting are round shapes and sinuous curves.

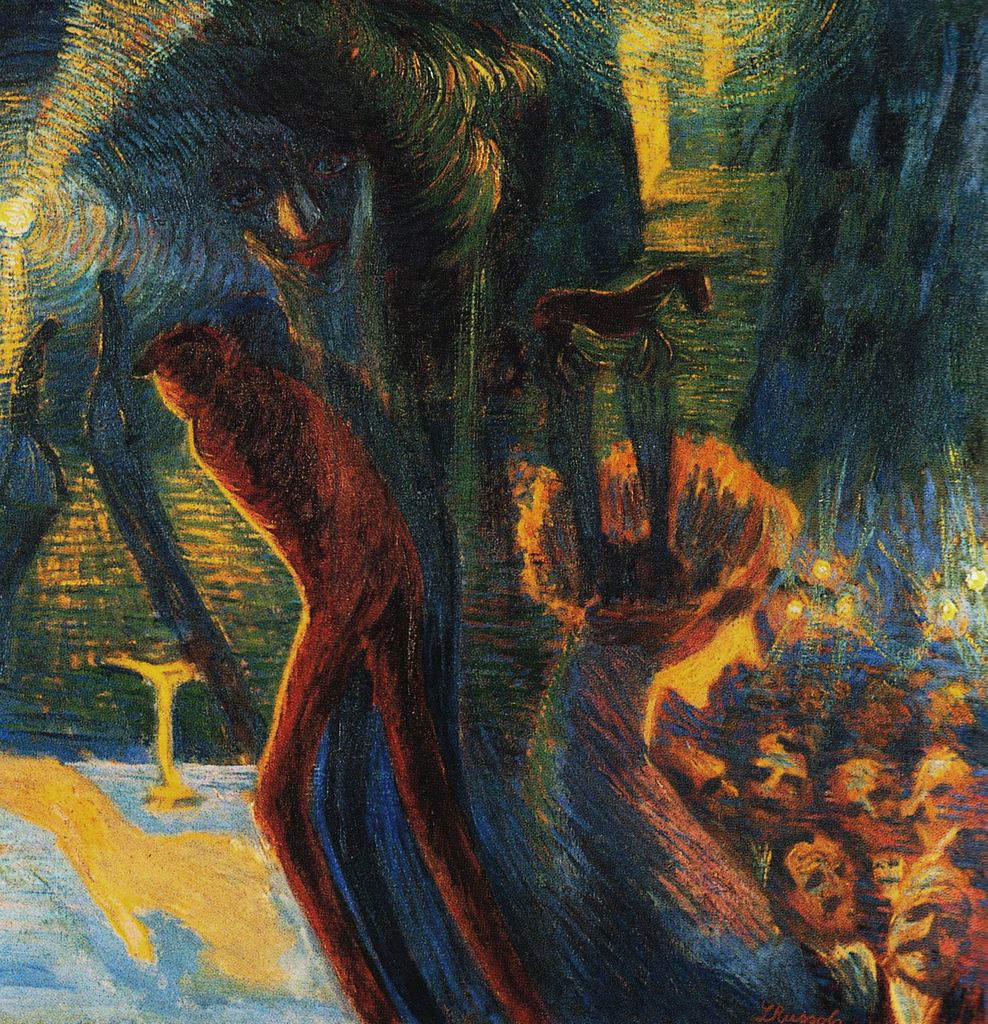

A decidedly peculiar work is Ricordo di una notte (1912) in which Russolo has placed on the canvas a collage of images and situations experienced during a night, as if they were dreamlike flashes that call to mind sensations and emotions that resurface little by little. One can recognize people walking, street lamps, a crowd of people, female profiles and even a horse. In this last work, as in his previous ones, Russolo’s style is still very much influenced by symbolism and pointillism.

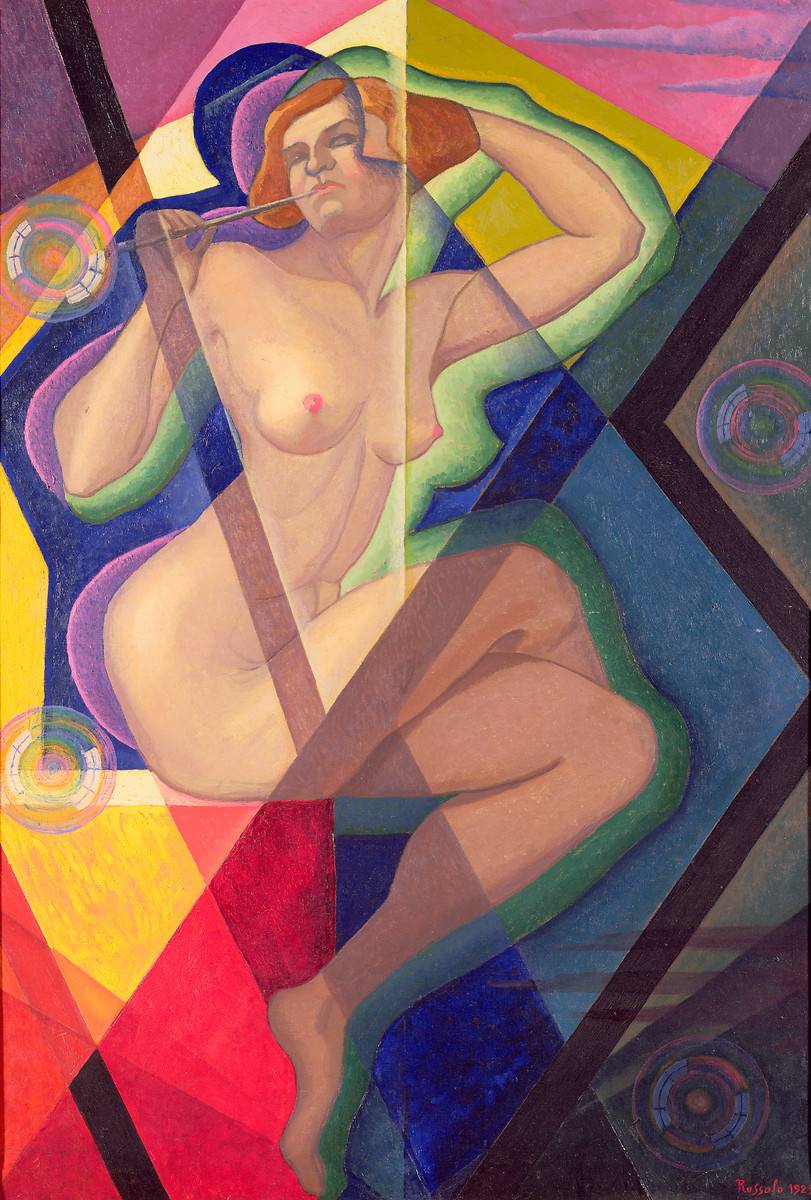

In Nocturne + Sparks of Revolt (1911), the first experiments with the decomposition of planes and objects and their serial repetition begin to emerge, which return especially in Plastic Synthesis of the Movements of a Woman (1912-1913). In this work, the movement mentioned in the title is proposed from different angles that are all brought back onto the canvas at the same time, in full alignment with the research on the same theme that Balla was devoting himself to, studying photography and animation.

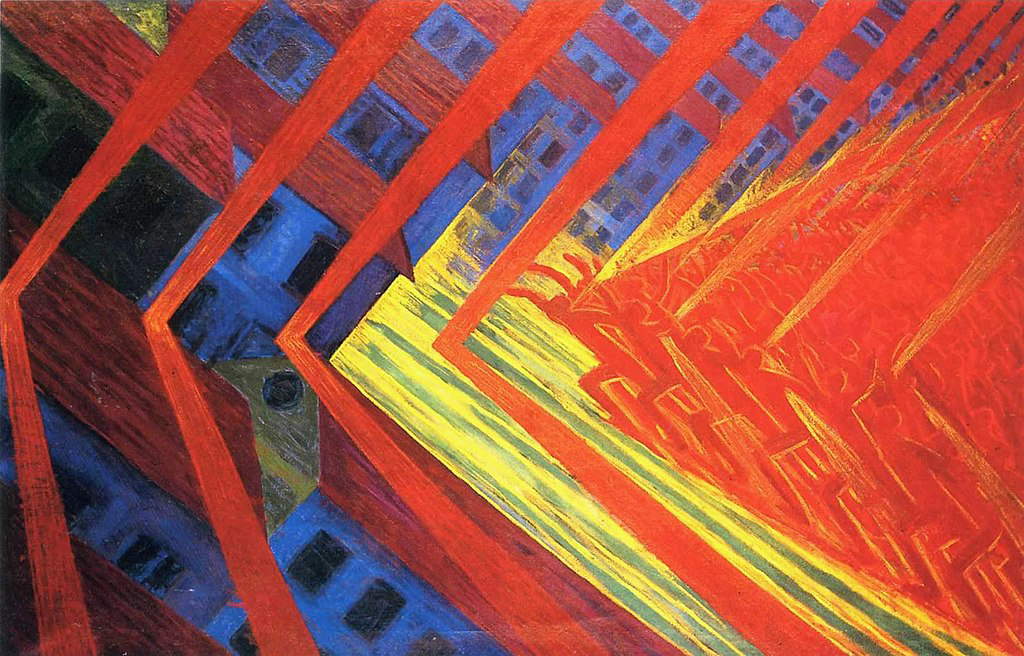

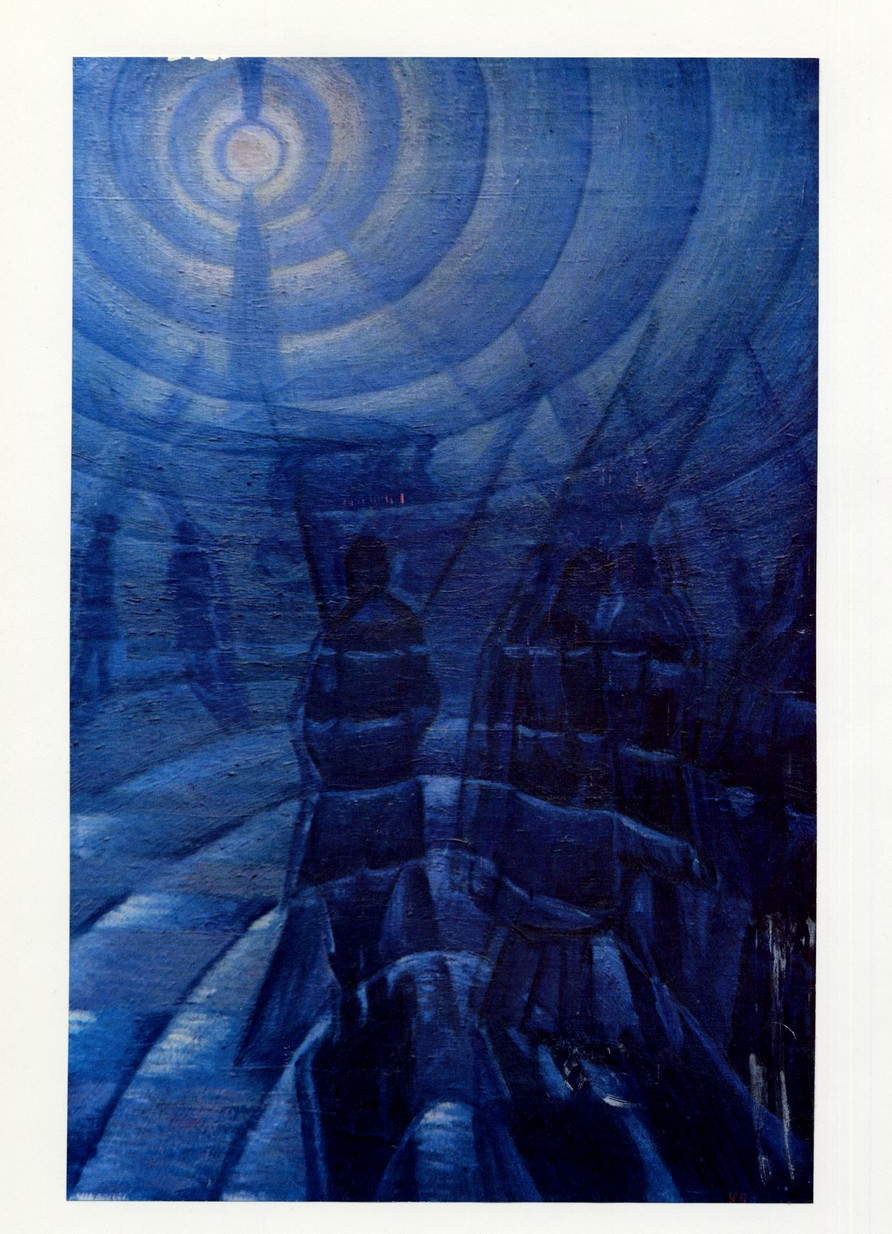

Another work very close to Balla’s researches is Solidity of Fog (1913), in which the atmospheric phenomenon is presented as a solid body, in the form of a series of concentric circles that are traversed by the artificial light of an electric lamp present above. The circles envelop the protagonists, a group of people who are probably soldiers (the first one holds something that looks like a flag). One of the paintings that encapsulatesalmost all of the Futurist ideals is certainly Dynamism of an Automobile (1912-1913). Automobiles were highly extolled by Marinetti and his people as a symbol that fully embodies vital energy as well as irrationality and madness. The very Futurist Manifesto read “... A racing automobile with its hood adorned with large snake-like tubes with explosive breath...a roaring automobile, which seems to run on machine gunfire is more beautiful than the Nike of Samothrace.” Russolo emphasizes the speed of the car through the use of very bright colors (red, yellow) and the usual “force lines,” similar to arrows, which were already present in La Rivolta and are present here as narrower on the left and wider on the right, to represent the victory of the car over air resistance. Also very close to Futurism and the analytical decomposition of forms is another work from 1912, Compenetration of Houses + Light + Sky in which an apparently simple urban landscape is decomposed into several planes that follow one after the other, interpenetrated by two intense beams of light.

In 1919, in addition to always being present in various national and international exhibitions, he published the pamphlet Contro tutti i ritorni in pittura, written in collaboration with Leonardo Dudreville, Achille Funi and Mario Sironi, in open polemic with the return to order that was appearing more and more frequently in artistic circles. After an interlude in which he abandoned painting, Russolo returned to painting in the 1920s with Ritratto di fanciulla (1921) in which the much previously vituperated return to order is actually embraced, in a kind of “spiritual symbolism,” reflecting the philosophical studies and insights to which Russolo had approached. Also of the same type is La Femme aux Bulles de Savon (1929). In between, i.e., around 1926, a work entitled Impressions of Bombardment, shrapnels and grenades that still recalls Futurist-like elements such as the dynamic and broken force lines that reproduce war actions, in a nonetheless figurative mode, reinforced by the presence at the bottom of a group of soldiers taking cover behind a low wall.

The 1938 work Aurora Boreale inaugurates the last phase of Russolo’s painting, characterized by full adherence to mystical and philosophical theories, in which landscape scenes built on horizontal planes and permeated by a sense of calm predominate, reinforced by the use of colors such as green, blue, and a few splashes of orange or yellow to represent light, such as Riflessi and Notturno, both from 1944. The only exception is Bach and Beethoven, from 1946, in which he returns to mention his great passion for music by inserting portraits of musicians within clouds above bright, blooming landscapes.

Russolo’s works can be found in several major museums, both national and international. In the artist’s hometown of Portogruaro is the painting Impressions of a bombing shrapnels and grenades (1926), in the municipal collection. In Venice, close to Portogruaro, there is Solidity of Fog (1912) in the prestigious Peggy Guggenheim Collection. At MART - Museum of Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto, the famous painting Perfume (1910) is preserved. Russolo’s first work, Self-Portrait with Skulls (1909) is kept in the Museo del Novecento in Milan. In our country it is also possible to see Lightning (1910) in the GNAM - National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome.

In Europe, it is possible to see two of Russolo’s works in Paris, namely Dynamism of an Automobile (1913) at the Centre Pompidou, Muse?e National d’Art Moderne, and La Femme aux Bulles de Savon (1929), in the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Also in France, more specifically at the Muse?e de Grenoble is Plastic Synthesis of the Movements of a Woman (1912-13). In Switzerland, at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, is Compenetration, Houses+light+sky (1912), while in Holland is The Revolt (1911) at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague. Finally, in London in the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art is La musica (1911).

A number of Russolo’s works are in private collections, including Notturno+Scintille di rivolta (1910-11), Chioma (I capelli di Tina) (1910), Ritratto di fanciulla (1921), Aurora Boreale (1938), Riflessi (1944), Notturno (1945), Bach (1946), Beethoven (1946).

|

| Luigi Russolo, life, works and style of the music futurist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.