Lucio Fontana (Rosario di Santa Fé, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968) is one of the best-known artists in the history of art as well as one of the most discussed by the public: in fact, one is often puzzled by his Buchi and his Tagli, which sometimes cause bewilderment in front of those who find them on display in a museum... or even simply posted on a social account. Yet, few works have been as revolutionary: their value, in fact, lies not so much in the technical simplicity of their realization (which in any case is only presumed: the cuts came to life after a rather elaborate process, which we have recounted in detail in a dedicated article), as in the path that the artist took to arrive at this insight, which creates a kind of caesura in the history of art.

The Italian-Argentine artist (Fontana was very keen to emphasize his origins, so much so that in several interviews he declared himself to be “Argentine”) was one of the great protagonists of the twentieth century, is recognized as the father of Spatialism, and came rather late to his best-known works, since his very famous Spatial Concepts date from the late 1940s. Before that, Fontana had experimented a great deal, with different materials, mainly plaster, bronze and especially ceramics: the artist always pursued the idea of a conquest of space, starting from the reflections of Umberto Boccioni, the only artist who, according to Fontana, had succeeded in giving life to this new road, to the discovery of the fourth dimension, that is, to an art that would be untied as much from the two-dimensionality of painting as from the static nature of sculpture, in order to expand into space. This is also why Fontana was unable to give a precise definition of his works: neither painting nor sculpture. But if we want to find further antecedents of the “conquest of space,” we could also mention the freedom and movement ofBaroque art, which in Fontana’s opinion had no equals, so much so that his early research with ceramics can be approached precisely to Baroque sculpture, for their dynamism, for the boldness of their development (it is enough to note how in many of his sculptures the different planes reflect light in so many different ways resulting in always surprising results). These are all experiences that later led him to the intuition of holes, cuts, and environments.

Reconstructing Fontana’s thinking is not difficult, because he is an artist who wrote a lot and gave many interviews. We can therefore consider him not only as the first and principal of the Spatialist artists, but also as their theorist: lucid, outspoken, often also very polemical (he collided, for example, with Emilio Vedova), Fontana was a multifaceted artist, up-to-date, educated, knowledgeable about the history of art. And we can say that it is profoundly unfair the attitude that part of the public reserves for him today, continuing to mock his works more than fifty years after their creation. An attitude that, however, was widespread even when the artist was exhibiting his work: “The critics have always maligned me,” he had to say in an interview with Nerio Minuzzo for L’Europeo in 1963. “But I never worried about it, I went ahead anyway and never took anyone’s greeting away. For years they called me ’the one with the holes,’ with some pity even. But today I see that my holes and cuts have created a taste, are accepted and even find practical applications. In bars and theaters people are making ceilings with holes. Because today, you see, even the people on the street understand the new forms. It is the artists, unfortunately, who understand less.”

|

| Lucio Fontana at the 1966 Venice Biennale |

Lucio Fontana was born on February 19, 1899, in Rosario di Santa Fé, Argentina, to Italian emigrants from whom he would inherit a passion for art: his father Luigi was in fact a sculptor, specializing in funeral statuary, while his mother Lucia Bottino was a theater actress. The artist attended school in Italy; he was in elementary school in Biumo, at the Tasso boarding school, and then attended the technical institute of the Collegio Arcivescovile in Seregno. At the same time he pursued his passion for art by beginning to practice in his father’s studio, since Luigi had also returned to Italy. At the outbreak of World War I, Lucio Fontana, in 1916, left school and enlisted as a volunteer in the infantry, eventually becoming an officer, with the rank of second lieutenant. In 1918, however, he was wounded in the Karst, was discharged with a silver medal for military valor, and resumed his studies, graduating as a building surveyor. In 1921 he returned to Argentina, where he devoted himself to sculpture, working in his father’s workshop. Initially he worked together with his father in the field of cemetery sculpture, but then took the path of research, which also earned him his first commissions in his native country. In 1927 he was back in Italy, where he enrolled at theBrera Academy of Fine Arts, where he became a pupil of Adolfo Wildt: in interviews, Fontana would later say that Wildt considered him, as well as one of his most gifted pupils, his continuator, but Lucio would disappoint him by embarking on an artistic path far from that of his master. He graduated from the Academy in 1929: the works of this phase are sculptures that bear much of Wildt’s influence.

The artist began to enjoy his first successes: in 1930 he participated in the 17th Venice Biennale (Wildt was the commissioner of the international exhibition), presenting two sculptures, and held his first solo show at the Galleria del Milione in Milan, curated by Edoardo Persico. Here, Fontana presented the sculpture that caused the break with Wildt, Black Man: “as soon as I came out of the Academy,” Fontana recounts in a 1963 interview with Bruno Rossi, “I took a mass of plaster, gave it the roughly figurative structure of a seated man and threw tar on it. Just like that, for a violent reaction. Wildt, of course, was quite hurt by it.” The artist continued on this path his research, first with plaster and then with ceramics: in the 1930s he was in Albissola Marina, where he collaborated with the ceramist Giuseppe Mazzotti. The artist left Italy again during World War II and moved to Argentina, where he taught decoration at the Academy of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires: here the artist signed, together with some of his students and young Argentine artists, the Manifiesto Blanco (“White Manifesto”), which can be considered the founding text of Spatialism. In the same year he made the first Spatial Concept and in 1947 signed the Manifesto of Spatialism together with Giorgio Kaisserlian, Beniamino Joppolo and Milena Milani. Before returning to Italy, he exhibited in 1949 at MoMA in New York in a group show of 20th-century Italian art.

Back in Italy, Fontana exhibited his first Ambienti spaziali in neon at the Milan Triennale in 1951 (the same year as the Technical Manifesto of Spatialism) and began to develop the research for which he is now universally known: in fact, the first “holes” date from the 1950s. The “cuts,” on the other hand, date back to 1958: they were first presented at the 1959 Galleria del Naviglio in Milan, then taken to Paris, to the prestigious Documenta in Kassel, and then again to the V São Paulo Biennial and several other important contexts. Fontana also does not stop researching sculpture, indeed: during these years he is always in Albissola Marina, where he has a studio from which splendid ceramic works continue to emerge. Instead, some important cycles date from the 1960s, such as the Oils, Metals, and especially the End of God of 1963-1964 and the Theaters of 1964-1966. The artist moved to Comabbio in 1968: here he passed away on September 7.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Fisherman (1933-34; colored plaster, 183 x 82 x 76 cm; Lucio Fontana Foundation) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Deposition of Christ (1954; plaster sketch, second version; Milan, Museo Diocesano “Carlo Maria Martini”) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, The four panels of the “Conte Grande” at MuDA in Albissola Marina. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Structure for the 9th Milan Triennale (1951; crystal tube with white neon; © Lucio Fontana Foundation) |

Contrary to what many might think when looking at his holes and cuts, Lucio Fontana possessed great technique, matured as a young boy in contact with his father and then refined by attending the Braidense Academy. His early achievements are similar to those of his master Adolfo Wildt: see, for example, the Madonna and Child of 1928, where the artist follows Wildt’s classical, sinuous, and polished style, while demonstrating the limitations of his lack of experience. However, Fontana was also able to create realist-inspired works (for example, the Fisherman of 1933-1934), which nevertheless lacked the degree of abstraction they would later achieve. The most innovative sculptures are from the late 1940s: they are highly animated, dynamic, Baroque-inspired ceramics, capable of reflecting light, creating effects that give further movement to the works. In a sense, therefore, they are already works that interact with space: among the most interesting examples in this sense are the Conte Grande ceramics made in 1949 and now preserved at MuDA in Albissola Marina.

The Technical Manifesto of Spatialism dates back to 1951: here the artist defines his intentions with extreme precision. “We conceive art as a sum of physical elements, color, sound, movement, time, space, conceiving a physical-psychic unity, color the element of space, sound the element of time, and movement developing in time and space. These are the basic forms of the new art that contains the four dimensions of existence. These would be the theoretical concepts of spatial art.” These were concepts that the artist had already expressed in Manifiesto Blanco. So what are the assumptions that lead to the holes and cuts? The first: theeternity of art and its impossibility of being immortal. That is to say, art is destined to die as physical matter (sooner or later, in the millennia, a painting or a sculpture will be destroyed), but as an innate need of the human being, art remains eternal in its dimension as a gesture. And a gesture cannot be destroyed. The holes and cuts are thus an exit from matter, a way to overcome it. Second, the conquest of space is a consequence of human history, which in the years of “holes” and “cuts” was, precisely, conquering space with lunar expeditions (a subject in which Fontana was always interested). “The discovery of the cosmos,” Fontana is said to have told Carla Lonzi in the interview later published in Self-Portrait, “is a new dimension, it’s infinity, so I pierce this canvas, which was the basis of all the arts and I created an infinite dimension, an x that for me is the basis of all contemporary art. Otherwise he goes on saying l’è un büs, and bye-bye.” Third: Spatialism represents the need to create an art of the future, an art that is “transmissible in space,” an art that lives in its time. An art that also makes us understand science, if you will.

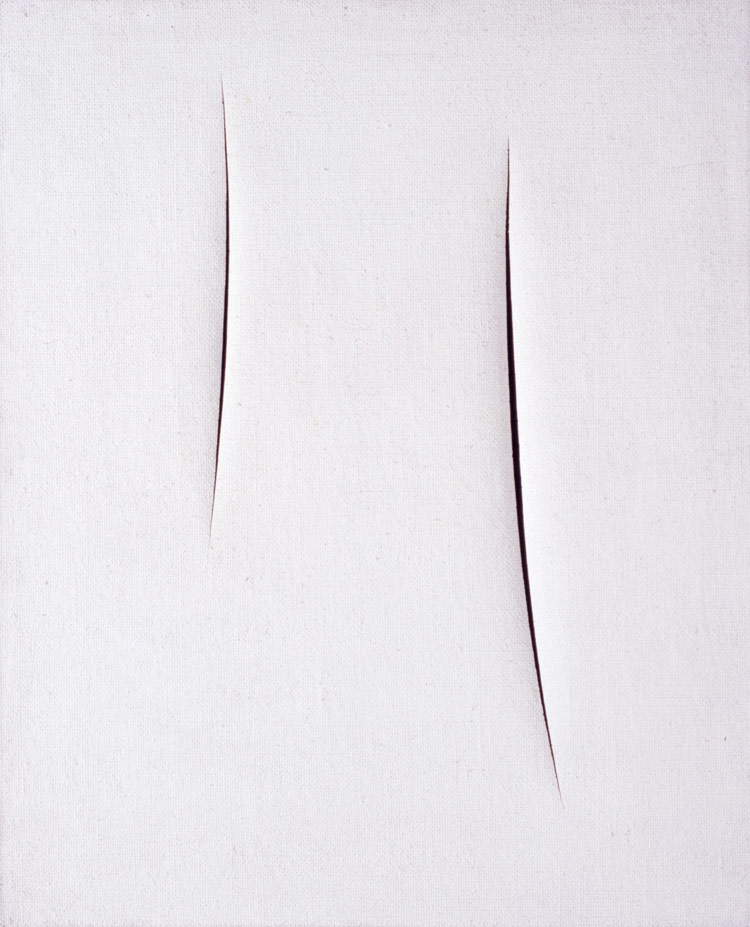

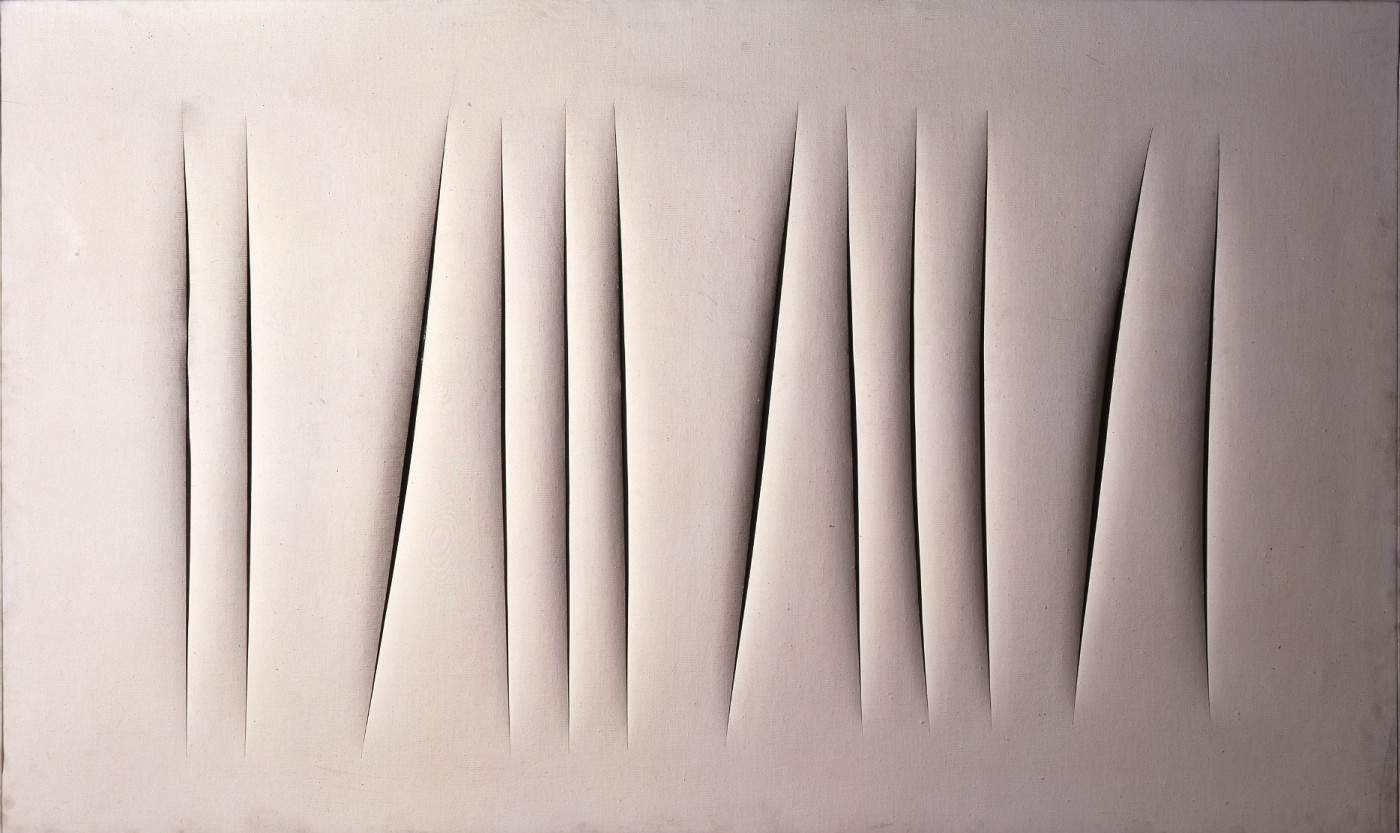

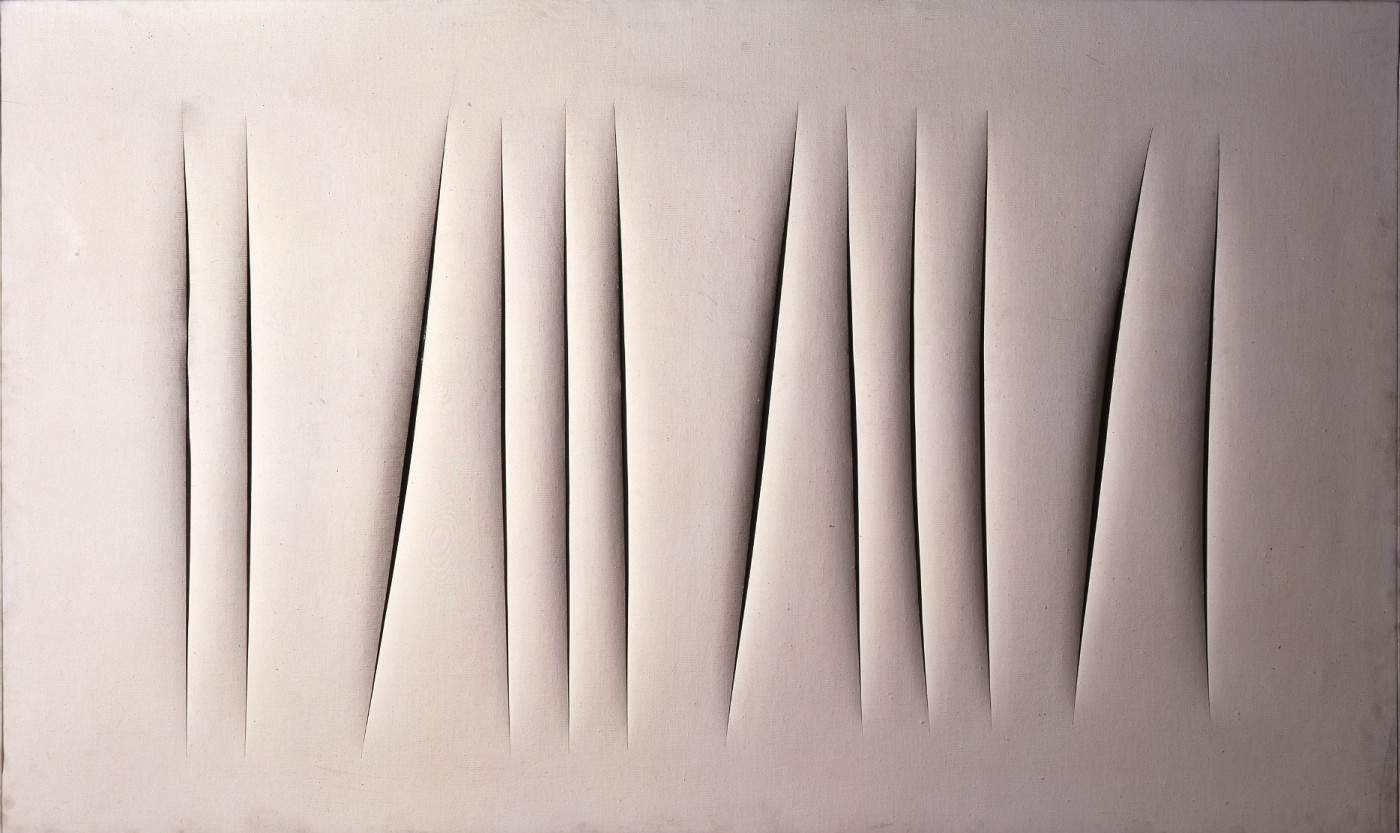

This, then, is why the artist called Spatial Concepts the holes and cuts. For the latter, moreover, Fontana did not even adopt the term “cuts,” but spoke of Waiting. Because the open cut projects us before a new dimension, waiting for something new to happen: it is as if beyond the canvas there is something expanding in space, just waiting for us to catch it. Among the critics who best understood the scope of Fontana’s revolution we can include Gillo Dorfles(at this link you can read his explanation of Fontana’s holes and cuts).

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1959; watercolor on canvas, 100 x 81 cm; Rovereto, MART - Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, on deposit from private collection; © Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. 62 O 32 (1962; oil, slashes and graffiti on canvas, 146 x 114 cm; Milan, Fondazione Lucio Fontana; © Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1964; cementite on canvas, 190.3 x 115.5 cm; Turin, Galleria d’Arte Moderna). © Lucio Fontana Foundation |

“A scientist,” Fontana said in 1965, “is locked up in his laboratory and works for the masses, for humanity. I in my profession as a painter, by making a painting with a cut, I don’t want to make a painting: I open a space, a new dimension in the orientation of contemporary arts: the end of sculpture or a tradition of painting in the sense of easel; however, it is also a new dimension of the cosmos. I, in my little discovery, the hole, I did not want to decorate a canvas: I broke this dimension; beyond this hole there is a new freedom of interpretation of art, the end of a traditional art, of this tri-dimension, for a dimension that is infinity: it is going towards the future.” Although it is the artist himself who speaks these words, it is from here that one can start to understand the greatness and importance of Lucio Fontana’s cuts. The artist was among the first, along with other greats such as Alberto Burri, Afro Basaldella, and Giuseppe Capogrossi, to found an art based on gesture. Moreover, with holes and cuts Fontana laid the groundwork for overcoming three-dimensionality. Again, Fontana’s works can almost be considered the first in art history to represent infinity, and they would open up important later research (such as that of Enrico Castellani).

And again, the cuts are a way to overcome the fiction of art: it is as if Fontana were telling us that the real world is not the one on the painting or inside the sculpture, but it is the one that opens beyond the slash. A discovery that Fontana arrived at with great lucidity. Moreover, Fontana can be said to have definitively overcome the third dimension, thanks to an art capable of occupying space (most evident in his Spatial Environments). Moreover, considering the works as “concepts,” Fontana can also be considered one of the precursors ofconceptual art, placed along the road leading from Duchamp to the art that would develop from the mid-1960s. Lucio Fontana is ultimately one of the greats of twentieth-century art history.

Lucio Fontana’s works are preserved in various museums around the world. In Italy, works by Fontana can be found at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, the Museo del Novecento in Milan (where a room is entirely dedicated to him), the Museo Diocesano in Milan, the MART in Rovereto, the MADRE in Naples, the GAM in Turin, the Museo Novecento in Florence, at the Casamonti Collection in Florence, the Museo Revoltella in Trieste, and the MAGI ’900 in Pieve di Cento. Works by Fontana are also preserved at the Vatican Museums. The MuDA in Albissola Marina (the city where the artist had the studio from which his ceramics were created) preserves a good nucleus of Fontana’s ceramics. Toward the end of his career, the artist was very prolific, because by his own admission he was asked for “holes” and “cuts” all the time: as a result, the artist produced a lot of them, although he did not get as rich as one might think from the million-dollar quotations that some of his works reach at auctions today. Several commercial galleries have works by Fontana that are regularly exhibited in major exhibition-markets in Italy and abroad.

|

| Lucio Fontana: life, works, the importance of cuts |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.